Acquiring and Optimizing Sustainable Relationships for Good Solid Cash Flow Streams. Or, Speaking with Plants.

Considering the connections between language and landscape, as well the disconnections that can occur when the former is used to frame intentions towards the latter, e.g. #sustainability, in this essay for Temporary continent., Lital Khaikin proposes a radical re-reading of space that privileges the plantlike qualities of longevity and simplicity over consumption and growth.

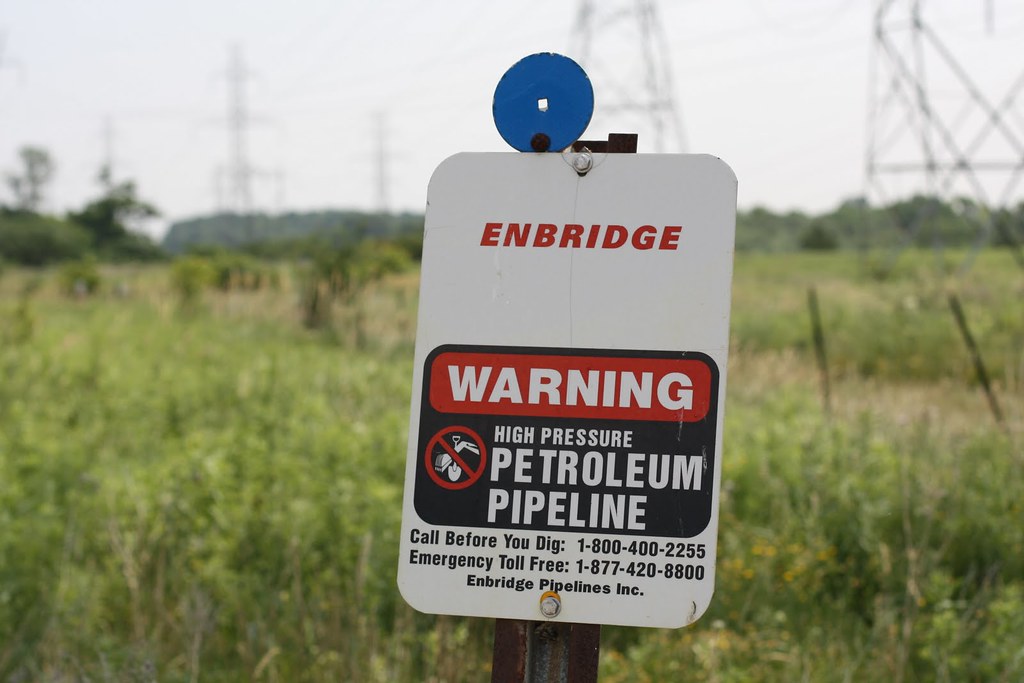

Enbridge pipeline marker. Photo by Environmental Defence Canada, CC BY-NC 2.0

The first stirring indicates life. The first gesture indicates meaning. The first word indicates intention. Language is a point of departure for the values we hold. Does a language have a beginning and end, like those we assign to a river? The mouth of this “river” is where we approach language, but, like the unclear headwaters, the story begins much earlier.

A river begins inside of the heart of a mountain—inside the moan of thunder—spun from headwaters, an almost-silent pond spiraling with a whispering thread of water disappearing into the forest to flow and flow and flow. The song of a whale echoes through ocean waters—that were indeed once the beginning of rivers—anthems of aliveness and companions to those like the salmon who return to their natal waters, traveling upstream, their memory feasts digested inside the bellies of some of the ancient swimming makers of milk. A river begins on the edges of stories. We travel to the depths of the beginnings of the river when we ask our grandmothers to share something from their childhood. A river begins inside the grief of forgetting. A river begins in the fingertips of a weaver.

Maureen Walrath

The Language of Responsible Care™

It is through the remoteness of words that so many of us manifest our relationships to place—conjuring the significance of an environment through borrowed assumptions, locating ourselves within some predetermined coordinates, inhabiting a place only after we have already decided on its limits. We are obedient to politicized terminologies, vocabularies shaped by curricula that are afforded to the few, ephemeral hashtags that accumulate social capital. If so much of our experience and sense of responsibility toward land is shaped by the most profitable of words, what do we find behind these terms?

Landscapes are deeply personal. I find that there is great incongruence between how fast technologies change landscapes and how slow we are to culturally absorb or adopt to those changes. Our identities are often connected to a very static rendering of a place—we often haven’t seen what it was before “us,” or what it might be. That limited vision often means we fear landscape change because we fear losing that which defines us.

Roopali Phadke

Line 3 Debate and the Anthropocene is an essay by Bianca Acevedo Gonzalez, shared in John Kim’s Anthropocene and the Media seminar. Gonzalez explores the contrasting discourse around Canadian energy multinational Enbridge’s Line 3 pipeline replacement project—between the ways in which Dakota and Lakota peoples, and extractive companies, each relate to the land. “Through my analysis of the videos,” Gonzalez writes, referring to a collection of videos that encompasses work produced by the non-profit organization Honor the Earth, by Native activists, and in turn by Enbridge, “I found that Enbridge focused on the economic benefits of the construction of the new Line 3 while activists focused on the environmental, cultural and spiritual impacts of the pipeline project.”

On one hand, there is what the land can provide for us. The agency we have to take what we need from it for monetary profit—where development is permitted because it promises capital gains, and value is immediate. In this imagining, there is no such thing as free space—you might even say there are no more landscapes. Every place is limited by borders and a specific use; privatized, exploited for its potential value, and in this way imprisoned within itself.

On the other hand, there are the teachings of elders. The requirements of wild rice. The beauty of places associated with human spirituality and ritual, or tended to by non-human beings. The imagining of a time far beyond the present moment. The respect given to a place that can exist only for itself.

The justification of these qualities is challenging for legal systems that demand a linear message of growth, development, capital. The seductive term of progress is defined by return-on-investment, by the ability of companies to perpetuate their own businesses. What other effects does this numbing have on us?

The best developments are community driven processes. The challenge is time and patience. Community processes are slow and often circuitous. Developers are challenged to respond to many and competing voices, and lean on committees and officials to mediate. The other challenge is the investment landscape, which privileges placeless development and quick turn-around times.

Roopali Phadke

Placeless development leaves us with locations determined by the value we find in them—speculative value, mineral deposits, strategic territory design. Our plans and maps are not illustrations of emotional networks, but deeply divisive contracts of ownership over resources.

Gonzalez focuses on Enbridge and the specific issue of the Line 3 project in Minnesota, but such branding that centers on sustainability through the lens of “Economic Benefits” is widely adopted by oil and gas companies, mining giants, and chemical conglomerates to justify their projects. Defining sustainability ultimately means owning the words to shape this definition. These proprietary definitions can then be used to create smokescreens around corporate strategy as, for example, with the Canadian-initiated Responsible Care™ “global product strategy” that was adopted in 1985 by the International Council of Chemical Associations.

The Chemistry Industry Association of Canada (CIAC) describes this Ethic: “Through Responsible Care®, CIAC member-companies strive to ‘do the right thing and be seen to do the right thing’.” Such value statements are frequently trademarked. A marketing sleight of hand, a slogan for charitable programs, awards, and children’s educational activities on Earth Day, or World Water Day. Today’s crisis is tomorrow’s woke image management campaign.

A curious glance at what’s trending for #sustainability on Twitter yields a number of companies using the “findability” of the word to position themselves as thought-leaders and drive traffic to their content. Zurich Insurance introduces carbon-emissions measures for its offices. A Brand Contributor for Bayer writes a think-piece on “sustainable agriculture” for Forbes’ BRANDVOICE Paid Program. A bottled water company is promoted on finance.yahoo for using aluminum “custom branded bottles” in which to sell its premium water.

This will be a battle of vision. There are many who are quite happy with the status quo and the way they know and enjoy the river. Change is both frightening and seems unnecessary. It’s hard to imagine returning the river to a pre-industrial path. Yet, for many in our communities, especially for native peoples, the built river today is an embodiment of a settler colonial vision that is full of pain. Removing some of the river’s shackles might be an important part of healing our relationships with each other.

Roopali Phadke

Block (Line 3) Party in St. Paul, Minnesota. Photo by Fibonacci Blue, CC BY-NC 2.0

“To us, sustainability means safeguarding our future social and economic viability,” writes German chemical conglomerate Bayer on their Environmental Awareness page. On their Sustainability page, Barrick Gold Corp. declares, “Barrick’s sustainability vision is to create long-term value for all our stakeholders”.

In the 2018 Enbridge Sustainability Report, President and CEO Al Monaco defines sustainability as: “focused on delivering long-term value for our stakeholders—an approach that’s essentially our definition of sustainability in our business.”

After defining to whom the definition of sustainability belongs, another question is posed: who belongs in this vision of sustainability?

“My point is,” Al Monaco (or his Communications Manager) writes, “that this is not an entirely altruistic view. While Enbridge believes that building sustainable relationships with Indigenous Nations connects directly to each of our core values—Integrity, Safety and Respect—we also believe that it is integral to our business case.”

Elsewhere, Al Monaco writes, “Our relationships with landowners, communities and Indigenous groups are essential to our long-term success”.

Of course these relationships are essential to a company’s business case; dissent poses an investment risk, threatens to slow down or cancel projects. Sustainability is the imperative of companies to make superficial adjustments that enable them to influence policy on their terms, and continue making their profits.

The supposed rights of Indigenous nations, and the “sustainable relationships” that companies like Enbridge build, are seemingly based on a version of collaboration that does not challenge colonial sovereignty, and which does not impede corporate entitlement to profit. In this version, those who are permitted a voice can speak so long as they concede to the economic priorities of big business, so long as their value as workers contributes to the continued exploitation of resources. Such an “imagined future” simply does not permit a world without the Enbridges or Bayers. But what if these businesses and their shareable commitments to sustainability are not welcome?

Weaving and Listening

In an article titled The Environment as Freedom: A Decolonial Reimagining, Malini Ranganathan describes the importance of making atypical connections between environmental justice, and race, class, and gender politics, as an act of decentering white settler narratives and ethical paradigms around land use. “To remember history is not to lament it,” she writes. “Rather, it is to purposefully take stock of the magnitude of damage wrought by various forms of discrimination and to devise interventions that redress the source of that discrimination.”

There is a deeply embedded form of violence in the reductive ways in which we perceive and speak about our environments. Binary views place us, as humans, at odds with the intelligence and agency of land. Along with human relations, it is also important to see how the damage of capitalist, colonial extractivism extends to all beings.

When they are seen as one vast and singular “land,” plants are made to disappear. They are denied the individuality that is so luxuriously afforded to humanity. When a blade of grass is invisible, rather than uniquely present, it is easier to trample on it.

Cradle woven by Maureen Walrath. Photo courtesy of artist

Each time I weave a willow vessel, I go on a psychic, emotional, physical journey. Time changes shape and beginnings and endings are remembered in the ancestral memory within my hands and the willow—the willow keeps the time. In this process I am asking the willow to become a basket to hold all kinds of space, life, and death. Each time I weave I feel I am being asked to change form, grow more courageous, emulate the strength and resilience of the willow. The weaving is a prayer for the wildly complex world we are part of. The burial vessels are seeds of beauty and story, woven up and planted as a dream remembering relationships to death and dying, old songs, the way we let our tears overflow and become the waters that also surround our days in rivers, creeks, oceans, estuaries.

Soul boats—sailing with the waters the willow soak in, through my hands, and into the hearts, homes, lives of the ones who will fill them. I contemplate the ecology of death and dying and all of the life birthed from the beautifully woven patterns in the baskets. How we as humans participate in the ongoing story of this life and how our tending and transforming in craft/art/beauty strengthens and brings vitality to our human communities and the ecosystems we are a part of. I wonder how my body vessel can be as intricately woven as these baskets and wonder what a human culture would be like that had in its daily rhythm the weaving hands and filling up of such vessels. I continue to ask the question of how the weaving wants to live in these times and how these vessels can be vessels of healing and not perpetuate the same extractive, exploitative, hungry greed within capitalism. I’ve started naming this work post-capitalist cradle and coffin weaving, the work and exchange all within a watershed. I consider how a living weaving practice can bring empowerment and crucial information to the humans around me in relation to the way we come in and the way we go out of this life.

Maureen Walrath

As a basket-maker, Maureen Walrath’s practice challenges the role of objects we take for granted in a culture of mass-production. Our most vulnerable states, of birth and death—even these are doused with a petrochemical opulence, a lush extractivism. Caskets made of granite and marble, cradles made of plastic, glues made of animals, ancients who buried themselves with trinkets and money. Even at the very edges of our humanity, we are obsessed with consumption.

Baskets are symbols of optimism and promise, implying that they can be filled. But this same potential also implies a limit: a basket is only capable of being filled to its specific capacity. The promise of abundance is bound to the vessel’s ability to contain it.

Coffin woven by Maureen Walrath. Photo courtesy of artist.

Change is slow and a companion. To create a changed relationship with materials rooted in reciprocity and non-extractive approaches, we need to listen for and travel the story that is alive in all of the materials we come into relationship with—become vulnerable, grow humble, and be willing to face our ignorance in participating in extractive and exploitative ways. In knowing or attempting to know the story of a material, we can understand how many hands and whose hands were asked, or not asked, to create, move, twist, turn, take—and where the oppression, heartache, and grief lies within resource and material extraction so that we might find another approach.

We can honor our bodies and their limits, boundaries, and work-rest rhythms. I feel when we live in our bodies in a way that is non-extractive, we will approach the body of the earth in a non-extractive way—we can offer beauty, work, restitution, reverence and make space for gratitude for the abundance we are continually given in this life. We can learn from our ancestors, the ways they formed relationship with materials and resources, and the way they related to the rhythms, patterns, and wisdom of the earth. We don’t need progress or growth—we can turn inward or towards the ones right around us to learn from that community-ecosystem-bioregion, and create from and with that community-ecosystem-bioregion. We can start to spiral.

Maureen Walrath

Gonzalez writes, “Corporations don’t just build around earth’s resources, they build on top of them or remove land altogether”. To disappear land, as if to disappear someone, alluding to a politically motivated crime, a secret execution. By removing land, what is left underfoot? How do we rebuild relationships with something that we are actively disappearing? What part of ourselves do we give back to the land? By seeing extractive methods as criminal acts, by aligning with ethics that see capitalist extraction as a form of environmental genocide, what possibility does this open for human responsibility to the land we inhabit?

In her book entitled Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer writes about what we can learn from observing lichen. “Their success is measured not by consumption and growth,” she writes, “but by graceful longevity and simplicity, by persistence when the world changed around them.”

Do we dare give power to plants? To see objects not as products of materials or resources, but composed of many bodies of knowledge? “Our indigenous herbalists say pay attention when plants come to you,” writes Kimmerer, “they’re bringing you something you need to learn.” In a culture that listens to the non-human, art becomes a form of quoting their wisdom.

I am continually forming and reforming answers to this question and how it relates to colonization, supremacy, and the intergenerational trauma living in this place, the so-called United States of America; and how my daily life choices and movements potentially contribute to the perpetuation of settler mentality, or work to dismantle settler mentality and heal. How to be in place, part of a place, to be a place?

I’ve been asking, what does it mean to be fully alive in a place, to move with and learn from the rhythms of the seasons among and with other humans, and within the lives of all beings. In A Wizard of Earthsea, Ursula K. Le Guin speaks to the intimate relationship with plants, fictional or not: ‘When you know the fourfoil in all its seasons root and leaf and flower, by sight and scent and seed, then you may learn its true name, knowing its being: which is more than its use.’ Being in a place means learning its true name. Being in a place means listening to the language that has been there and is there—human and non-human. Learn the names of the rivers and creeks, and the names they had before those names. To be in a place is to be a part of the body of a place; slow down and quiet long enough to form a relationship with fully embodied sensual awareness. As a human, to be in a place means we can listen for what is needed and respond—whether in song, stillness, planting seeds, cooking, making art, weaving, making love, expressing anger, grieving, showing up, or coming together.

Maureen Walrath

What if we are to radically change the way we see space—relating to an environment not as a demarcated location, but an aggregated presence of a multitude of individuals? Not a lifeless combination of coordinates, but a moving, breathing, sensing crowd that we encounter, attune to, interact with? Not as a territory to be owned, but as a living and sensing being, or plenitude of beings? Then, as with any consensual relationship, we cannot assume that we can take; we must seek permission from these multitudes. And perhaps, they will say to us, no.

Re-wilding depends on perspective—are we referring to large ecosystems with/without humans or the act of rewilding one’s self. I think the answer creates a different sensibility. Since so much has been written about rewilding landscapes, like reintroducing predators, I’ll make it more personal. For me, rewilding is about seeing where wildness already exists within and around us and cultivating the wildness you seek in the world. This can be tending a surly garden or adventuring beyond one’s creature comforts. In the case of the Mississippi, it can mean imagining a river without walls and then helping bring that into being again.

Roopali Phadke

We may not be prepared for this. It would require of us to collaborate, bond, and make friendship with our environments. We already know that plants respond to touch, to singing and music, to animate and lively spaces—brushed and misted, moving with the movement of the world. There is trauma buried into generations of plants, from the rumbling of heavy machinery, the automated blades of ploughs, the choking exhaust, and leaking contaminants. As if having learned the burden of a friend, we must struggle with what do with this information. But is this not also a science? This spring of curiosity and responsibility is the very beginning of science. This root of empathy muddies the headwaters, mystifying the terms with which we can create our coming beginnings.