Blackhawk Park Is Indigenous Land (Beyond Acknowledgment)

The effects of the Anthropocene are not experienced evenly and certain regions and their communities have been hit by its repercussions harder than others. The seminar Over the Levee, Under the Plow took as its starting point one of these spaces: Blackhawk Park, a “wounded place” where the colonial ties of the Anthropocene become painfully palpable. While histories on settler colonization all too often treat it as a thing of the past, the authors of this seminar reflection urge us to consider how colonial legacies continue to seep into a colonial present.

Banners from Dylan Miner’s project “The Land is Always” installed on the banks of the Mississippi River at the opening event programming for Anthropocene Drift, September 25, 2019. Photograph by Katie Netti/Meredith Dallas

Arriving in cars, vans, pickups, and canoes, a group slowly assembled under an overcast sky on the banks of the Mississippi in a place called Blackhawk Park, near the small town of De Soto, Wisconsin. As organizers of Anthropocene Drift, we believed it was necessary to acknowledge that we were gathering on Indigenous land. On Ho-Chunk land. However, we chose not to begin our program, Over the Levee, Under the Plow, with a formal land acknowledgment. Rather, we viewed the five-day seminar—itself building on eighteen months of focused research and planning—as a prolonged land acknowledgment, and also a concerted attempt to move beyond acknowledgment. That is to say, we need to move from words to actions as we grapple with what it means to live and work as settlers on Indigenous land. On Ho-Chunk land, in this case.

Land acknowledgments are necessary but insufficient gestures of accountability to Indigenous peoples in the colonial present. Chelsea Vowel, a Métis writer and teacher from manitow-sâkahikan (Lac Ste. Anne) in Alberta, Canada, invites us “to start imagining a constellation of relationships that must be entered into beyond territorial acknowledgments.”1 She encourages settlers to “start learning about [their] obligations as a guest in this territory.” One of the very first obligations as a guest is to know the names of your hosts, and to listen closely to them. In the case of our seminar, doing so elevated homelands and places of belonging instead of field stations, a perspectival shift suggested by Ojibwe artist Andrea Carlson.2

“Moving beyond territorial acknowledgments,” Vowell continues, “means asking hard questions about what needs to be done once we’re ‘aware of Indigenous presence.’ It requires that we remain uncomfortable, and it means making concrete, disruptive change.” Acknowledgment is therefore not an end itself but a provocation to disrupt, to “unsettle”—figuratively and literally—our relationships to the land, to history, and to one another. As three white settlers, artists, and academics, we welcomed participants to lands that are not rightfully ours and spoke with voices authorized and amplified by white supremacy. Ours is the white, middle-class subjectivity—already a complicated assemblage of varying identities—that the anthropologist Heather Anne Swanson describes as “predicated on not noticing. […] on structural blindness: on a refusal to acknowledge the histories we inherit.”3 So we began Over the Levee, Under the Plow by unsettling the very land on which we gathered—acknowledging our complicity in the violence that secured our place there.

Here and Now

Anthropocene Drift began in a place usually marked as an ending.

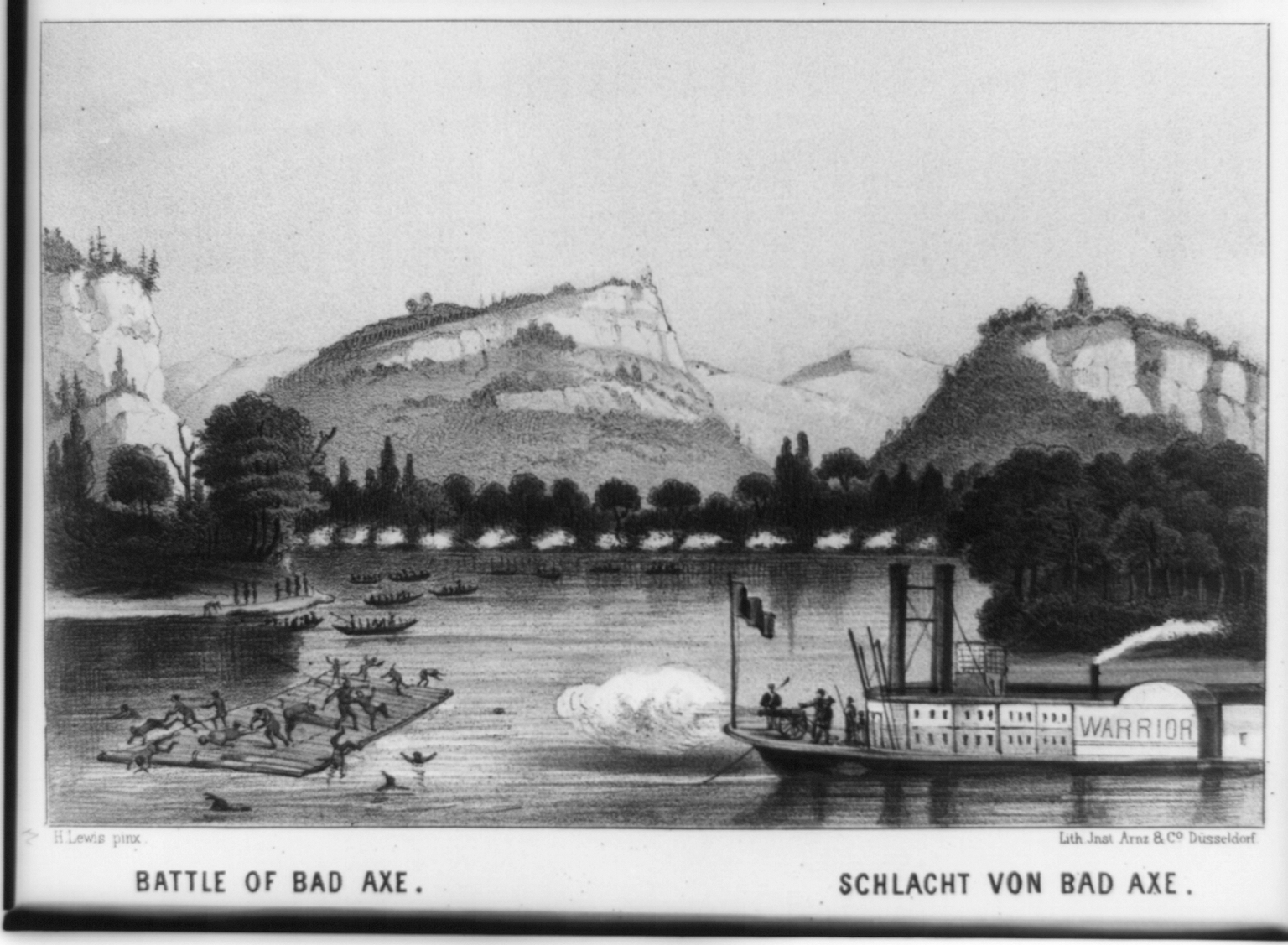

Not far from where we gathered in Blackhawk Park, a massacre took place. On the first and second days of August 1832, the US Army and Illinois militia fired on a group of starving, exhausted Native Americans—mostly Sauk and Meskwaki, but also Kickapoo, Ho-Chunk, and Potawatomi—as they tried to cross the Mississippi River to safety. Their leader, Black Hawk, had already tried to surrender several times during the so-called war that bears his name, and the massacre began even after he once again waved a flag of truce. When soldiers began firing, Black Hawk’s band had little choice but to provide cover for those trying to cross. Soldiers on the bluffs streamed down to shoot at closer range, while a military riverboat fired on retreating families with cannons. Although some made it to safety, many of those who crossed the river were soon captured by the US-allied Dakota. Militiamen gleefully mutilated corpses; sharpshooters deliberately targeted babies. When reproached for these actions, one volunteer soldier coldly replied, “Kill the nits, and you’ll have no lice.”4

Officially called the Battle of Bad Axe, the event produced carnage so one-sided that it has been described as a massacre since the 1850s. Of the nearly 2,000 people who had joined Black Hawk in April to contest the terms of a fraudulent treaty and return to their ancestral village of Saukenuk to farm, only thirty-nine survivors were captured at the conclusion of the massacre. Many had died on the journey before reaching the Mississippi, while others no doubt managed to escape during the fighting. Black Hawk surrendered himself to American authorities a few days after the massacre and was imprisoned just down the river in Prairie du Chien.

“Battle of Bad Ax,” 1857 engraving by Henry Lewis. Image from Library of Congress Online Catalog.

The Black Hawk War inaugurated an era of massive change to physical, cultural, and political landscapes throughout the region. A newsletter from the Dane County Historical Society summed it up: “Without an Indian war threat, Wisconsin Territory was created just four years later and rapid settlement produced statehood in 1848.”5 The genocidal war unleashed a new phase of regional settler colonization and justified an aggressive campaign of removal of the northern Indigenous peoples, including the Ho-Chunk, Meskwaki, Iowa, and Kickapoo Nations. Historian Jeffrey Ostler argues, “After the Bad Axe Massacre, federal officials seized the moment to separate Indians from their lands. Whether they had supported Black Hawk, remained neutral, or assisted the United States government made no difference.”6 Beginning in 1832, the Ho-Chunk suffered multiple removals—from Wisconsin to Iowa, Minnesota, Dakota Territory, and Nebraska. Of course, some Ho-Chunk refused to be removed, and remained in or returned to each of these places.

The Bad Axe Massacre has a prehistory, a context. A land cession treaty had been signed in St. Louis in 1804 by a Sauk delegation that did not expect to enter into land negotiations and lacked the authority to do so, leading many members of the Sauk Nation to regard the treaty as invalid and to resist American attempts to enforce it. This fraudulent treaty and increasing squatter incursions into their traditional territories prompted the Sauk, Meskwaki, Ho-Chunk, and Potawatomi to support the British during the War of 1812. Black Hawk himself fought in that war and incorporated British insignia into his wardrobe for the rest of his life. Under the terms of the Treaty of Ghent of 1814, the US assumed actual, rather than nominal, control over the so-called Northwest Territory, and settlers began arriving en masse. At the conclusion of that war, Saukenuk, the Sauk capital where Over the Levee, Under the Plow ended, was the largest city in what would soon become Illinois. Occupied mostly during the growing season when the Sauk returned from their winter hunting grounds in what is now Iowa, Saukenuk’s log houses were surrounded by vegetable and corn fields. The lead deposits of northwestern Illinois and southwestern Wisconsin were mined seasonally by Ho-Chunk, Sauk, and Meskwaki women. These well-stewarded resources were extremely attractive to settlers, and from the 1820s both Sauk and Meskwaki leaders began to complain of finding white squatters living in their Saukenuk homes, stealing their corn, and mining the ore with people they had enslaved.

Commemorative marker to the Treaty of 1804 installed by the Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma and the Meskwaki Tribe/Sac and Fox of the Mississippi in Iowa. Photograph by Ryan Griffis Flooding at Blackhawk Park, May 2019. Photograph by Sarah Kanouse

In this historical context, we can understand Blackhawk Park, the nearby town of Victory, and the Black Hawk Trail, which we followed over five days, as “environmental fantasies” of our “settler ancestors.” As Potawatomi scholar Kyle Powys Whyte asserts:

Many Indigenous peoples in North America […] are already living in what our ancestors would have understood as dystopian or post-apocalyptic times. In a cataclysmically short period, the capitalist–colonialist partnership has destroyed our relationships with thousands of species and ecosystems. […]

[…] Settler ancestors wanted today’s world. They would have relished the possibility that some of their descendants could freely commit extractive violence on Indigenous lands and then feel, with no doubts, that they are ethical people.”7

We must acknowledge this environmental fantasy/dystopia, too, and sit with the discomfort acknowledgment arouses.

We gathered at Blackhawk Park because of the massacre that took place on August 1 and 2, 1832. But that is obviously not all that has happened there, and those who survived the massacre have relationships to this place that cannot be reduced to a simple narrative of domination and extermination. As George Thurman, a direct descendent of Black Hawk and the former Principal Chief of the Sac and Fox Nation in Oklahoma, explains:

To say that Black Hawk still has relevance to the Sac and Fox implies a hold to the past, and that’s true because we are all connected, a part of those who came before and holding on to what they taught us for those yet to come. However, our past is not a fixed point that grows farther away with each new generation; instead, our past is like a bloodline, living, breathing, and growing as we grow. […]

As a descendant, my perspective about Black Hawk is more personal. He is a very real part of what I bring to the Sac and Fox Nation as its chief and who I am as Sac and Fox. I have visited the places where he walked and could place my own footsteps where his had been. I stood on the banks of the Mississippi River at Bad Axe where 179 years ago I would have been a target for the guns and cannon just for being Sauk.

So many of our people died there. The massacre still echoes within us. It was a tragic ending. But I, a member of that same tribe, stood there at the place of “ending” and saw my people of today make offerings at the riverside. Black Hawk fought so his people could live, and there, where one might think it all ended for us, we stood, remembering our people in the way they left to us and that is uniquely ours.8

Blackhawk Park can also be understood as a “wounded place,” which geographer Karen Till describes as “present to the pain of others and [embodying] difficult social pasts.”9 In this sense, the confluence of the Bad Axe River with the Mississippi is not unlike Bdote, the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers, which has been the focus of Dakota artist Mona Smith’s ongoing healing work.10 In places such as these, we must challenge ourselves to understand, following historian Christine DeLucia, “how memories of devastation exist relationally alongside those of regeneration.”11 If the Mississippi Valley can be understood, in part, by tracing Indigenous removals and land cessions, it can also be understood in terms of refusals and returns, particularly among the Ho-Chunk and Meskwaki Nations. The effects of removals are felt today and every day, and shape what Lakota historian Nick Estes calls “the Indigenous political practice of return, restoration, and reclamation of belonging and place.”12 As the ecological devastation initiated by the wounding of places like Bdote and Bad Axe spreads across the planet, how to remember, care for, and address sites of intergenerational and profoundly uneven trauma become ever more urgent questions.

Here and Now

We began our public program forty-one hours after an equinox; six days into the student-led Global Climate Strike; a few months after the water that covered Blackhawk Park for much of the spring and early summer receded; and at the end of the hottest decade in human history.

We all followed different paths to arrive at Blackhawk Park that September afternoon.

Some of us drove to the park from South Central Wisconsin and Central Illinois, the middle of the so-called Corn Belt, where rivers with names like the Rock, Vermilion, Platte, Mackinaw, Menominee, Embarras, Wisconsin, Kaskaskia, and Sangamon—along with many drainage ditches and canals—connect, eventually, to the Mississippi River. The dominant plants found in that territory for most of the year—genetically modified yellow dent #2 corn and soybeans—require vast amounts of energy and chemical inputs. When discussing the Anthropocene, this landscape is a seemingly easy case study as a totally transformed ecosystem, as environmental historian William Cronon described years ago in Nature’s Metropolis.13

Shortly after massacres like Bad Axe secured US ownership over the Midwest, the series of Swamp Land Acts passed between 1849 and 1860 “gave” lands considered swamps and wetlands to states so that these ecosystems could be converted into private property and made “productive.” This federal legislation did not result directly and immediately in what geographers like Michael Urban have argued is, for all intents and purposes, the permanent transformation of the region’s hydrological and ecological composition.14 Rather, the policies were only one step that prefigured the work that speculators and farmers would undertake to remake the land in their own image through drainage ditches and subsurface tile drainage systems. The near total elimination of wetlands and grasslands in this region was also a colonial war—this time against what anthropologist James C. Scott has referred to as the ungovernable spaces of wetlands and mud, and, of course, against the lifeways that were sustained by them.15 The vast fields of corn and soy that we see today are local instantiations of the colonial and capitalist land use and plantation economies that exist around the world. This model is, in fact, one that has been exported at an enormous scale to Brazil and Argentina. Like all plantation economies, the conceptualization of the land as a storehouse of resources waiting to be extracted also includes the conceptualization of bodies, both human and otherwise, as expendable forms of capital.

The effects of this physical transformation are reverberating across the biosphere. A week before the launch of our seminar, the New York Times reported on an article in the journal Science that shows “the number of birds in the United States and Canada has fallen by 29 percent since 1970. […] There are 2.9 billion fewer birds taking wing now than there were 50 years ago.”16 Blackhawk Park lies within the Mississippi Flyway, a vital migration corridor for more than 325 bird species, which pass by there twice a year en route from breeding grounds in Canada and the northern United States to wintering grounds along the Gulf of Mexico and in Central and South America.

Two weeks before the launch, the New York Times reported that “this year’s flooding across the Midwest and the South affected nearly 14 million people.” The article noted: “The year through May 2019 was the wettest 12-month period on record in the United States, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Edward Clark, director of NOAA’s National Water Center, said, ‘This is a year that will remain in our cultural memory, in our history.’”17 The year continued to be very wet into fall. The Midwest witnessed—and was unevenly impacted by—historic flooding along the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers and many of their tributaries. “The fields are washing away,” Missouri farmer Kate Glastetter told Pacific Standard magazine in June, a month when Blackhawk Park was submerged beneath the swollen Mississippi.18 The silt left by receding floodwaters added to the layer—already several meters thick in many places— of what scientists call “post-settlement alluvium,” or “legacy sediment,” the result of nineteenth-century Euro-American agricultural practices that initiated widespread erosion and washed upland sediment into the region’s valleys. The economic stress posed by the most recent floods may exacerbate the epidemic of depression among American farmers, whose suicide rate in 2018 was already twice that of combat veterans.19 And although words like “Anthropocene” and “climate crisis” are controversial or even unknown in many rural communities, it is possible to identify within them what environmental researchers Ashlee Cunsolo and Neville Ellis call ecological grief: “the grief felt in relation to experienced or anticipated ecological losses, including the loss of species, ecosystems and meaningful landscapes due to acute or chronic environmental change.”20

Mourning Nature in the (Colonial) Anthropocene

Seventy-two years and forty miles from where we gathered at Blackhawk Park, ecologist Aldo Leopold dedicated a monument to the last Wisconsin passenger pigeon, which was shot dead in September 1899. In his speech at the unveiling, Leopold reflected: “We have erected a monument to commemorate the funeral of a species. It symbolizes our sorrow. We grieve because no living man will see again the onrushing phalanx of victorious birds, sweeping a path for spring across the March skies, chasing the defeated winter from all the woods and prairies of Wisconsin.” In dedicating what was perhaps the first monument to extinction, Leopold called out the actions of previous generations—“Our grandfathers,” he declared, “[believed it was] more important to multiply people and comforts than to cherish the beauty of the land in which they live”—while also reserving his greatest grief not for the birds themselves but for the loss of cultural and aesthetic relationships that mainstream settler American culture had developed with that species.21

Monument to the last Wisconsin passenger pigeon, shot at Babcock in September 1899 adjacent to an effigy mound of the Woodland culture, ca. 350-1350 CE. Wyalusing State Park. Photograph by Sarah Kanouse Okjökull memorial plaque. Photograph by Rice University (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Leopold’s elegiac warning foreshadowed the recent rash of extinction-related monuments, both physical and virtual. These monuments, like the one initiated by Cymene Howe and Dominic Boyer to Iceland’s vanishing Okjökull glacier or Maya Lin’s multimedia biodiversity memorial What Is Missing? (2009–), frequently employ an non-specific, present-day human “we.” Billed as a “global memorial to the planet,” Lin’s artwork is dedicated to:

The species that have gone extinct.

The species that will go extinct in our lifetime.

The species that we will never know because we destroyed their habitats before we could ever know them.22

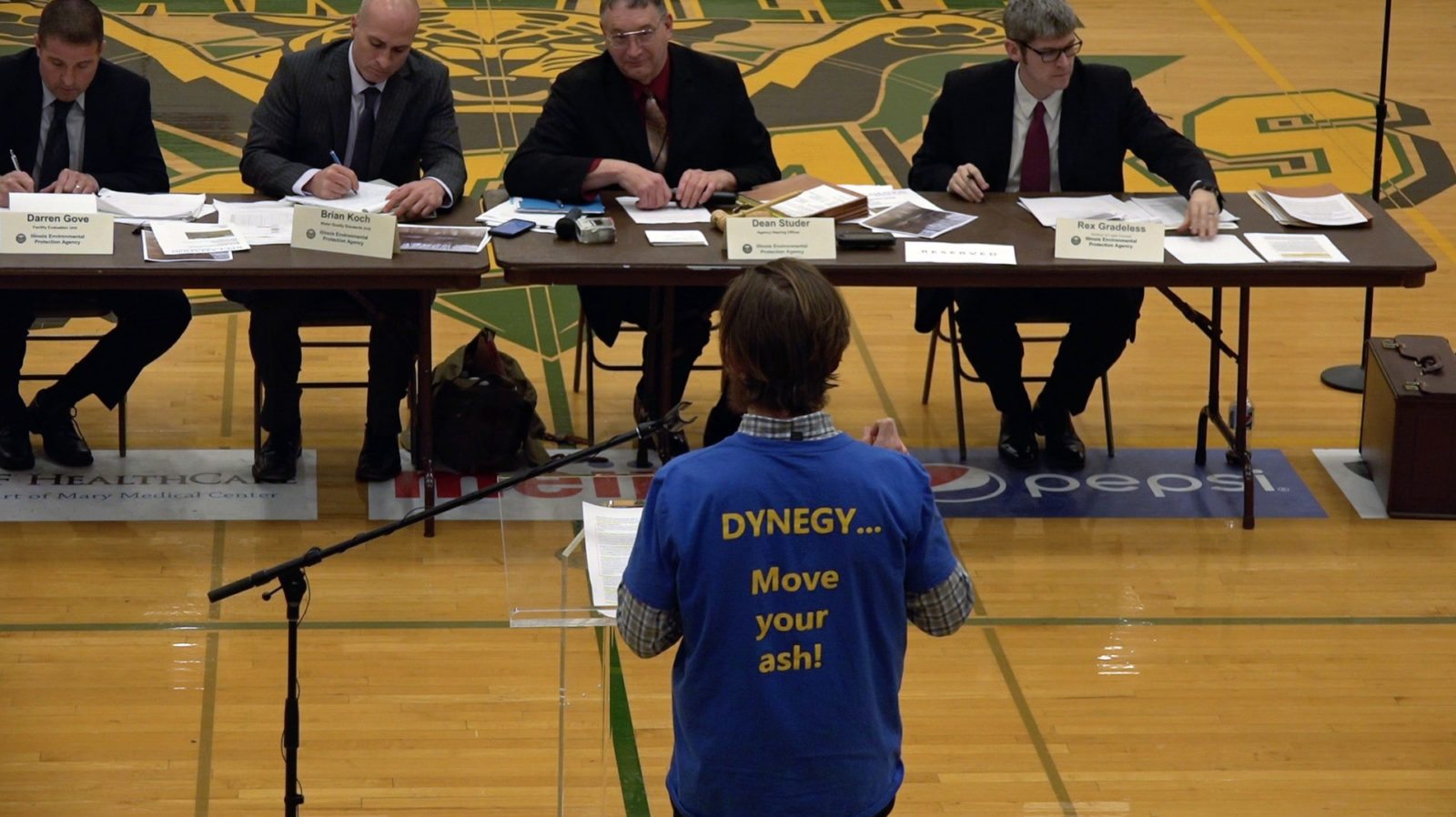

Community member testifies at an Illinois EPA Public Hearing for 401 Water Quality Certification, Danville Area Community College, March 26, 2019. Photograph by Ryan Griffis

The glacier memorial’s text, written by prominent Icelandic author Andri Snaer Magnason and unveiled in July 2019 to much fanfare, similarly addresses a future human reader: “This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.” Leopold’s pigeon plaque is more explicit in its accusation: “This species became extinct through the avarice of and thoughtlessness of man.”23

These monuments are significant because they point to an ongoing shift toward considering longer, multigenerational timespans and finding “nature” and cultural relationships with the natural world grievable. Yet in invoking an undifferentiated “we,” they risk reinforcing the already widespread narrative—epitomized in Leopold’s plaque—that humanity writ large is responsible for these losses. However, as Kyle Powys Whyte reminds us, some humans have long benefited from the very forces that generated the losses that we now grieve or find “ourselves” suddenly vulnerable to.

The very real grief that climate change can and should engender—and that creative projects are uniquely suited to hold space for—risks becoming an eco-variant of what Renato Rosaldo called “imperialist nostalgia [which] uses a pose of ‘innocent yearning’ both to capture people’s imaginations and to conceal its complicity with often brutal domination.”24 Those of us who have inherited the structural blindness endemic to white, middle-class American culture must insistently recognize the staggering ecological costs already born by Indigenous peoples long before the last passenger pigeon fell from the sky.

The Colonial Anthropocene

In starting our seminar at Blackhawk Park on September 25, 2019, we were making two implicit propositions. The first is that what has been called the Anthropocene—the intensification and industrialization of land and resource use that has led us to the brink of ecological collapse—is not the inevitable product of humanity writ large but rather the consequence of Euro-American colonialism and the capitalist economic systems it built. Anthropocene Drift (Field Station 2) tried to make visible not just the Anthropocene but also the colonial Anthropocene, which is to say it sought to reveal how ongoing processes of colonization are transforming the Earth. The (colonial) Anthropocene is everywhere, of course, but it is particularly palpable in places like Blackhawk Park, Indian Lake, and the former site of the Badger Army Ammunition Plant in Wisconsin, where our field station programming took place.

Our second proposition is that the Anthropocene is an uneven spatial phenomenon. Debates about the start of the Anthropocene are usually framed in temporal rather than spatial terms. When did it begin, we ask, not where did it start? Dates are singular rather than plural. The Anthropocene started in either 1492, 1610, 1619, or 1950. It didn’t start in all these, plus a million other times and places. We contend that the Anthropocene is both a world geo-historical event and a highly variegated and textured condition that is experienced unevenly and very specifically across space, species, gender, race, and class. Anthropocene Drift asked not when did the (colonial) Anthropocene begin, but, instead, where is it most visible? And where, how, and by whom is it felt most intensely? Part of our interest in the Driftless Area was thus pragmatic, insofar as it ties the Anthropocene to colonialism in place(s).

It’s ironic to think about the Anthropocene in terms of temporal golden spikes. Spikes are, after all, driven into space, not time. They are staples connecting one thing with another, an attempt to bridge a gap. According to historian Manu Karuka, that other famous golden spike—the one that connected the First Transcontinental Railroad—“did not suture the Union after the Civil War; it symbolically finalized the industrial infrastructure of a continental empire where none had existed before.”25 But if you wanted to place a spatiotemporal golden spike to mark the start of the Anthropocene in the Upper Midwest (or, as it was known from 1787 to 1803, the Northwest Territory), the confluence of the Bad Axe and Mississippi Rivers—that is to say, Blackhawk Park—would be an ideal location.

Yet framing the “quotidian Anthropocene” as starting here risks reducing this place to the Bad Axe Massacre and reinforcing what literary scholar Mark Rifkin calls “settler time,” a temporality that consigns Indigenous people to the past while selectively admitting them to a present defined entirely in settler terms. Only within settler time could the Black Hawk conflict be described as the “last Indian war east of the Mississippi.” This designation is another instance of the “phenomenon of lasting,” which Ojibwe historian Jean O’Brien identifies as a “rhetorical strategy that asserts as a fact the claim that Indians can never be modern.”26 The Black Hawk War was obviously not the “last Indian war,” nor was it the last conflict over settlement or sovereignty in the Midwest—or anywhere else. It wasn’t even the last Black Hawk war. The longest and most destructive conflict between so-called pioneer immigrants and Native Americans in Utah history, which occurred thirty-three years after the conflict in Illinois, is also commonly referred to as the Black Hawk War.

Similarly, calling the Anthropocene a new geologic time that “we” are all in only makes sense in the framework of settler time. If we adopt the Anthropocene as a useful analytic framework, we must take care that it not become a totalizing, teleological narrative, an extension of Rifkin’s “settler time” to which Indigenous people might be admitted, but only on terms that ultimately undermine the heterogeneous temporalities that are forms of sovereignty existing beyond settler recognition.27 For this reason, our Field Station largely did not engage the Anthropocene as a definitional project, whether by establishing its temporality or locating exemplary anthropocenic phenomena. We were most interested in how the Anthropocene is to be survivable and, crucially, for whom. We must remember that the colonial project that undergirds the Anthropocene was never fully successful: there still exist biocultural and temporal “refuges,” sustained by the descendants of the people colonization failed to exterminate. Anthropocene Drift (Field Station 2) was a protracted effort to learn about what novelist and essayist Gerald Vizenor calls “survivance” (“survival” plus “resistance”) in the face of extended, violent ecosocial trauma.28 While we sought to listen to and learn from Indigenous people, we do not hold up Indigenous “resilience” as a model for settler society, such that the refusal to be eliminated becomes yet another resource for Euro-Americans to plunder. Rather, we sought to strengthen relationships with and between Indigenous individuals and groups and among settler descendants, out of which we aimed to build practices of survivability that foreground both difference and justice in the (colonial) Anthropocene. Clint Carroll, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, and the seminar’s concluding speaker, describes this as “relational activism,” explaining:

For Indigenous peoples, the political is environmental—our struggles are most fundamentally about and for the land. This is not a liberal stance, not an environmentalist stance, not a Marxist class-struggle stance. It is an Indigenous stance that may touch on points within the above positions yet offers the world something distinct, something fundamentally different that seeks to benefit all those who have a right to life, that is, all things living—and this includes plants, animals, landforms, waterways, and the many other beings with which humans must maintain respectful relations.29

Recognizing fundamental differences between Indigenous and progressive Euro-American political traditions is essential for any meaningful exchange. In the especially fraught context of settler–Indigenous contact—which has long mixed violent conquest with romanticized celebration, and forced assimilation with cultural appropriation—we must treat concepts of “reconciliation” and “understanding” with caution, lest they become yet another settler “move to innocence.”30 Rather, by highlighting both what is relational and what is incommensurable, we hope to live a better, more responsive, and inescapably Earth-bound life in place, whether Indigenous, settler, “arrivant,” or all three.31

Grounded Relationalities

In the Vermilion River watershed near the border of Illinois and Indiana, there has been something of a successful campaign against the unregulated impacts of waste from coal-burning power plants, which of course are always located alongside rivers. A coalition of urban and rural organizations—including the Prairie Rivers Network, Faith in Place, Eco-Justice Collaborative, and Earthjustice—mobilized a large, politically diverse population to pressure the Illinois government to force power companies to deal with the problems posed by mountains of coal ash. At one Illinois Environmental Protection Agency hearing, residents packed a gym at Danville Area Community College to argue that the river needs to be understood as a living thing that cannot be legislated or controlled by engineering solutions. These residents represented the largely white, rural, working-class population that voted for Donald Trump in 2016, and we have no illusions that they—whether individually liberal or conservative—were representing anything other than their own interests, in the form of maintaining their property claims and protecting the health of their families and friends. But we could also choose to hear at least some recognition of what one of our participants, the historian Alyosha Goldstein (along with his coauthors Jodi Byrd, Jodi Melamed, and Chandan Reddy) has called “grounded relationalities”: “If the grounded relationalities of Indigenous philosophies might tell us anything, then, they remind us that knowledge must always remain grounded as the land calls to us and for us to find our place within the ongoing acts of interconnectivity that surround us.”32

How might the experience of these testifying Illinois residents, as settlers in the (colonial) Anthropocene, be mobilized toward living within it differently? Goldstein and his coauthors ask for a consideration of how land, “understood not as property or territory but as a source of relation with an agency of its own,” might make other possibilities available, possibilities that recognize the racialized and embodied histories that we have inherited and continue to create.

Although our Field Station research and public program centered Indigenous voices, the opening of the seminar did not include the visible participation of Native Americans in the spiritually, historically, and ecologically charged site of the Bad Axe Massacre. Early in our planning, we spent several weeks asking individuals we know in the Sauk, Meskwaki, Ho-Chunk, and Kickapoo Nations about the value of meeting there to address this history. Several of these people joined us for portions of the seminar but did not respond to or declined the invitation to meet us at Bad Axe. Bill Quackenbush, Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Ho-Chunk Nation, who led a four-hour tour with the group on the seminar’s second day, explained his reluctance: “Our internal perspectives, stories, and histories of this and many other traumatic events are only intended to stay within our tribal communities.”

Quackenbush helped us understand that an invitation to perform or narrate at this site of trauma is inappropriate. It is only within settler time that this “history” needs to be specifically addressed as such, since it is being actively lived in Indigenous communities every day. If the (colonial) Anthropocene is to be survivable, Indigenous people and settlers will have different roles. As Dakota medicine gardener Francis Bettelyoun explains in artist Corinne Teed’s booklet for the Field Station: “We [the Dakota people] are Indigenizing. We are not decolonizing. Your work is decolonizing.”33 Anthropocene Drift (Field Station 2) was our humble contribution to that ongoing work.

As we assemble these reflections a few months after the conclusion of the seminar, we continue to be mindful of the here and now, and how shifting places and times assert themselves and inflect our understandings of the (colonial) Anthropocene. The end of the year—the end of the decade—witnessed another UN Climate Change Conference (COP25), and teenage environmental activist Greta Thunberg is in the news again. This time it is not because of what she said, but because of what she didn’t say, and how she used her platform to center other voices, especially Indigenous voices. “Our stories have been told over and over again,” Thunberg said to delegates at COP25. “There is no need to listen to us anymore.” She continued, “It is people especially from the global south, especially from Indigenous communities, who need to tell their stories.”34