Edible Encounters

Tracing liminal landscapes from St. Louis to Ste. Geneviève

Large scale agriculture is a spatial practice that instills human agency and control onto the earth’s surface. But niches of ecological autonomy still persist between the controlled spaces of industrial monocultures. As Lynn Peemoeller observes, the foraging, preparation, and consumption of soon-to-be-extinct, wild, edible plants can aid their preservation by re-introducing them into our collective cultural memory. Through a series of food encounters along the Mississippi River, the author asks us to recognize the liminal zones of biodiversity that sprout between the spaces of industrial agriculture.

“You’ve got to eat it to save it” is a popular saying among slow food producers and eaters who work to preserve the biodiversity of native foods and food traditions facing extinction. It is a tried and true method of engagement. There are many rewards and pleasures that come from eating rare and carefully preserved foods. These foods, like the American wild persimmon found in the Midwest, often circulate story and mythology in and of themselves. It behooves us to pay attention not only to these foods for their ecologic significance, but also to the accompanying narratives and from what perspective they are told. There are many hidden hierarchies in these stories that lead to an accumulated homogenization of cultural capital. Like seeds, we pass these stories from one generation to the next by what comes natural to us: our collective practice of cooking and eating. When we consciously eat these foods, we participate in an ideological arc of past, grounded in the present and future.

Baked into the idea of “eating it to save it” is the anthropocentric relationship that humans have with biodiversity through breeding and natural selection. As much as the rise and fall of biodiversity on Earth has happened outside the realm of human interaction, the biodiversity of what we call food has very much to do with human interaction. This relationship has been well documented throughout time, and especially here, in the American Bottom—the extensive floodplains of the East St. Louis region. The ongoing work of paleoethnobotanists, whose archeological data goes back some 5,000 years, demonstrates how humans have manipulated plant productivity through seed selection from prehistory to present times.1 To understand that history helps us to understand farmland as a kind of cultural landscape where the production of space and human patterns are accumulated and impressed upon the contours of the natural environment,2 until we can no longer identify what came before the human.

We can seek out biological and cultural remnants of prehuman edible matter in any landscape. But the more we look, the more we find ourselves intertwined at every level. This project, Edible Encounters along the Mississippi, used a methodology of enactment and encounter to investigate examples of native biodiversity and foods of significance in the Confluence region. Working with edible matter can be particularly thrilling because it is alive. Like us, plants and seeds and animals are biologically programmed to reproduce. We can attempt to seek this life through an exploration of the landscape in the liminal sidelines of the river, looking for undomesticated, latent, lost, or forgotten examples of what has become wild.

As an instructive investigation—on the river, with students—Edible Encounters presented foods linked to place. It used specific assemblages of vegetables, nuts, beans, and other foods as curated objects that were then prepared in a group encounter and transformed into meals that have linkages to histories of place. The foods are intended to be eaten in order to be “saved,” or at least preserved, through a continuity of experience placed in a collective memory.

Edible Encounters also pursued relations between food and place in unforeseen encounters with the wild (what still gets called “wilderness”)3, offering a temporal investigation in what the place has to offer through foraging. Foraging asks us to look in detail at the landscape and ask, “What is edible here?” It enables us to seek real time and sometimes fleeting assemblages of edible material. Importantly, it calls upon the capital of knowledge and the currency of culture to know how to recognize the findings and what to do with them. Foraging along the banks of the Mississippi River offers an opportunity to recognize remnants of ecologic autonomy in pockets of wilderness contrasted against the larger surroundings of industry and agricultural monocultures. It allows us to imagine narratives and micro eco-communities that diverge from the vast monocultures and veer from the anthropocenic.

If you look at farmland adjacent to the Mississippi River today, you will not be shocked to see that the majority of field crops are contemporary monocultures, like corn and soy. These productive landscapes are the very opposite of biodiversity. In fact, fifteen or so miles of river adjacent to St. Louis and Illinois represents the transfer of so much commodity grain production infrastructure from land to water that it is known as the Agriculture Coast. From here, the grain barges move down the river to distribute their cargo for processing and export. Looking carefully at the places affected by the industrialized river economy, we see a well-worn landscape of urbanism, industry, and monoculture that belies this local industry’s significance at the global scale.

The influence of corn in particular is worth lingering on for a moment. As one of the world’s central commodities, corn plays a critical role in global food security today. It is also one of the most quintessential crops within the American identity. This elevated status may relate to the cultural emphasis on corn for the role it played in human settlement and agriculture, as it spread from its origin in Central America throughout North America. In the pre-Columbian city of Cahokia, adjacent to the Mississippi River and along the American Bottom, archaeologists date the adoption of maize at roughly 1000 ce. But it was only in the last century that it grew to become the dominant form of agricultural identity in the Midwest.

Edible Encounters gave us an opportunity to observe the contrast between the wild bursts of biodiversity in the marginal areas along the river and the widespread control of nature exemplified by the endless cornfields in this region. These series of edible encounters and territorial mash-ups offered interpretations of foods that have bioregional origins or are part of long-standing Indigenous traditions or both. It was an opportunity to look to Indigenous knowledge, tradition, and creativity to build collective narratives and memory through the shared experience of taste. Like the Mississippi River itself, these encounters paired planning with spontaneity and required participants to go with the flow.

St. Louis skyline from the river by Lynn Peemoeller

Edible Encounter 1: Mosenthein Island, eight miles north of the Gateway Arch in St. Louis

Quinoa with turkey broth, sunflower seeds, pumpkin seeds, and lamb’s quarters

The assemblage of ingredients for this Edible Encounter represents an overlap of geography of the Americas, as well as of time periods, with some demonstratable connectivity between past and present. It hinges on the relationships between cultivated and wild species.

Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) has achieved global notoriety for its highly nutritious, gluten-free seeds, although not long ago it was largely known as a place-based food domesticated and cultivated in the Andes mountains. It is in the Amaranthaceae family, which developed into various place-based varietals of Chenopodium throughout Central and North America. In fact, its cousin lamb’s quarters (Chenopodium berlandieri and Chenopodium album), which we found growing wild in the forested sand dunes along the Mississippi River, is widely distributed throughout North America and is considered a weed. But it was not always seen as such. Lamb’s quarters is one of the prehistoric crops known as the Eastern Agricultural Complex (EAC), a group of cultivated and domesticated species that supported the agricultural legacy of early peoples in the region. The common sunflower seed (Helianthus annuus) is also part of the EAC and has long been used because of its edible seeds that are rich in oil. It is difficult to know exactly what species commercial pumpkin seeds (genus Cucurbita, possibly Cucurbita argyrosperma) come from. We do know that another gourd relative, Cucurbita pepo, was cultivated as part of the EAC as early as 3,000 years ago. This squash was most likely dried and used as a container. The turkey broth represents the wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo and its subspecies), an iconic bird native to North America that has played a significant role in many Indigenous cultures for its meat, eggs, and feathers.

Edible Encounter 2: On the river

Alegrías de amaranto

It’s worth noting that, adjacent to the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, is an established Mexican American community with several tiendas and taquerias stretching up and down Collinsville Road. Just like the relationship between the city of Cahokia and the corn originally from Mexico that was cultivated here, the area’s contemporary Mexican American community not only thrives but provides vitality to the region. At one of the local tiendas, I purchased the original “protein bar”: the alegrías de amaranto. It is a popular Mexican sweet snack made with amaranth, sugar or honey, and nuts or raisins. Amaranth is in the same family as Chenopodium and is native to the Americas. It’s sweet. It’s snappy. It’s dense, but light. It makes an ideal traveling companion on a canoe trip.

Edible Encounter 3: Near Valmeyer, Illinois

The three sisters: delicata and acorn squash, tepary beans, and hominy

This assemblage represents the legend of the three sisters: beans, corn (also known as maize), and squash. These are vital crops and feature in the stories and cosmology of many Native American Nations. When planted together, the seeds works together in order to share benefits and thrive. The corn provides poles for the beans to climb up; the beans fix the soil with nitrogen, which benefits the other plants; and the wide leaves of the squash block out sunlight, retaining moisture and minimizing weeds. When cooked together, it is believed that their various enzymes work together to make carbohydrates, fats, and proteins more accessible to the body. Hominy is dried corn that has been nixtamalized, or soaked in an alkaline solution, which helps to dissolve the tough outer skin of the kernel. The kernels are then usually eaten cooked or ground into grits or flour called masa. Both beans and hominy were carefully procured from a small company called Rancho Gordo4, a heritage bean seller that works with small-scale growers all over the Americas to produce heirloom varieties.

Dried beans need some special care to revive them before they are edible. We did this by soaking them in a resealable baggie for seven hours while we canoed down the river. The wild bean that grew in this region at the time of Cahokia today exists only as historical evidence. Its genetic stock has been lost, but according to the anthropologist Gayle Fritz, it may have been similar to a small bean that comes from a drought-tolerant plant, known as the tepary bean (Phaseolus acutifolius).5 Tepary is a legume variety native to the Southwestern United States and Mexico. We also soaked a bag of white hominy (Zea mays), swollen kernels of corn that are often eaten in stews. We used two types of winter squash in the stew. The acorn squash (Cucurbita pepo var. turbinata) is very similar to what was being grown at Cahokia around 1000 years ago. I had brought with me several squash that had been grown and harvested at the Cahokia interpretive garden in the summer. Traditionally, people would slice the squash and hang it to dry to save it for the winter. I attempted such a long-term drying in my oven, and we were able to resuscitate the pieces with some water and red wine. We also used fresh delicata squash (Cucurbita pepo var. pepo) because of its sweet and dense flavor.

Edible Encounter 4: Missouri River campground

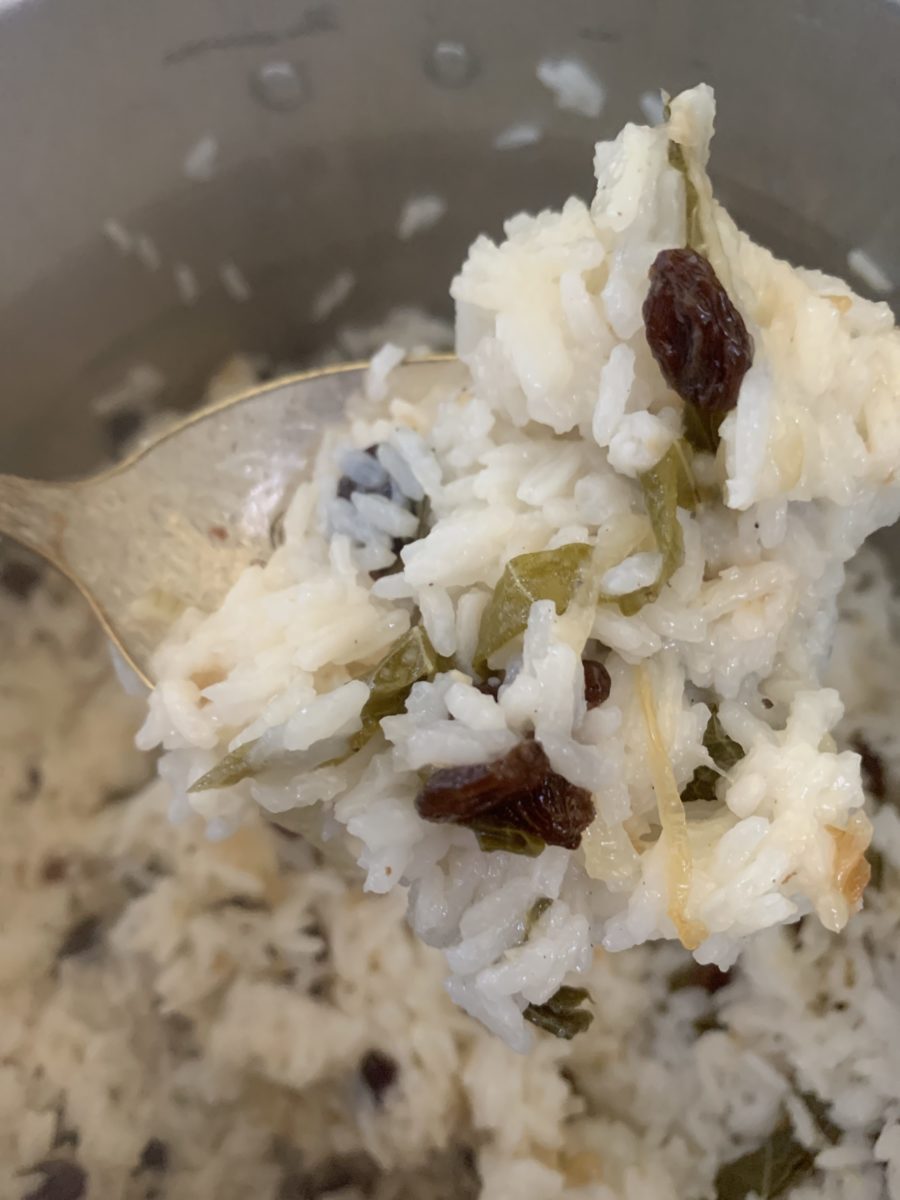

Hazelnut stew with apple and corn dumplings, rice with wild grape leaves and raisins

This encounter was an ambitious attempt to process hickory nuts in a traditional way, as people might have done at the height of the city of Cahokia. Fritz mentions how Cahokians were skilled in obtaining and processing tree nuts like hickory, acorn, and hazelnut.6 Hickory nuts were abundant in the Eastern Agriculture Complex, although the trees are no longer as abundant in this region as they once were. Cherokee today continue to make kunuche, a hickory-nut soup that begins with a laborious process of cracking and pounding the nuts and then forming the resulting paste into a ball for storage. When it is time to make the soup, the ball is dissolved in hot water, the shell fragments are picked out, and various other ingredients are added, such as rice, hominy, sugar, and salt.

We wanted to attempt to reenact this process on the river. However, I was not able to obtain a large enough amount of hickory nuts, so instead I was able to locally source a significant amount of American hazelnut (Corylus americana). We river travelers toasted the nuts over an open fire, pounded them to release the nuts from their shells, and sampled them. From a larger batch of already shelled hazelnuts, we pounded out a coarse meal, to which we added water and then placed over an open campfire. As the nuts boiled, diced apples (Malus pumila) were added along with big spoonfuls of dough, which turned into puffy cornmeal dumplings—made primarily from stone-ground cornmeal from the historic Weisenberger Mill in Kentucky.

The primary inspiration of the rice dish was the wild grape. Missouri is home to both cultivated and wild native grape species (Vitis labrusca and Vitis riparia). On our river journey, we found abundant wild grape vines along the shores of the Mississippi, but, in early October, there were no grapes left on the vine. However, the leaves were collected and boiled in salted water, making them tender and releasing a surprising sour, tangy taste. The boiled leaves were added to a Middle Eastern–themed pilaf of rice, raisins, and fried onions.

This meal was an attempt to enact the seasonal processing of hickory nuts, which has been vital to the nutrition of the Indigenous Peoples of this region as far back as the Late Paleoindian period (over 10,000 years ago). Fritz writes, “The fact that this food (Kunuche balls) is still made and consumed by many Cherokee people today says a great deal about persistence of native values and appreciation of long-standing traditions.”7This type of Traditional Knowledge is kept alive when traditions such as kunuche making are intently enacted and performed. Our use of the also locally available hazelnuts is an interesting substitute, and it brings to question why hickory nuts have a preferential relationship with Indigenous traditions over hazelnuts. Both are tree nuts and both were prolific in the region for thousands of years. Because of trees’ perennial rootedness in the land, I suggest that tree nuts have more long-standing agency in the landscape than any annual crop, like corn, which relies on humans to harvest and save and replant the seeds.

Campfire on the river by Lynn Peemoeller

Edible Encounter 5: Smoky, wet campfire

Junk food and s’mores around the campfire

As fellow Austrian traveler Tahani Nadim incredulously said to me upon watching some other river travelers grab a stick, spear a marshmallow, and start toasting it over the campfire: “This is something like a photo out of an American kids’ camping magazine.” Yes, indeed, s’mores are a critical food of Americana. Like German Stockbrot (stick bread), which also involves the ritual of finding the perfect stick and putting it in the fire to cook up a tasty treat, the making of s’mores brings people together around a campfire. Stories are sure to follow. Four-year-olds and forty-year-olds enact the tradition with equal enthusiasm. After all, who doesn’t like a gooey, sweet marshmallow, chocolate, and graham cracker sandwich? Apparently this year, in 2020, the s’more will celebrate one hundred years of campfire entertainment, first brought to us by the brand Campfire Marshmallows.

Postscript

Edible encounters are everywhere. They don’t require a canoe, a river, or an institution to program them. Yet a guided group encounter allowed us to develop an experiential narrative that helped us understand the connections between food and landscapes and the role humans have played in developing these over time. Edible encounters ask us to look, in detail, at the margins and transitions between places—from the highly controlled to the wild, and that which has also run wild. The contrast between the Mississippi River, its floodplain, and the adjacent fields provides one such liminal landscape to ponder human life along the river, from days long ago up until now. One thing we know for certain is that people have always needed to eat. Edible encounters have been, and always are, everywhere.