Fort Snelling’s Deep Time Stories

Centering upon a site that she is, on a quotidian level, deeply familiar with, Roopali Phadke ruminates upon what stories a “deep time” reading of what is now known as Fort Snelling in Minnesota could reveal. It is through a kind of “Anthropocenic reckoning,” she suggests, that we might begin to know more and know deeply about the human and non-human histories that precede us.

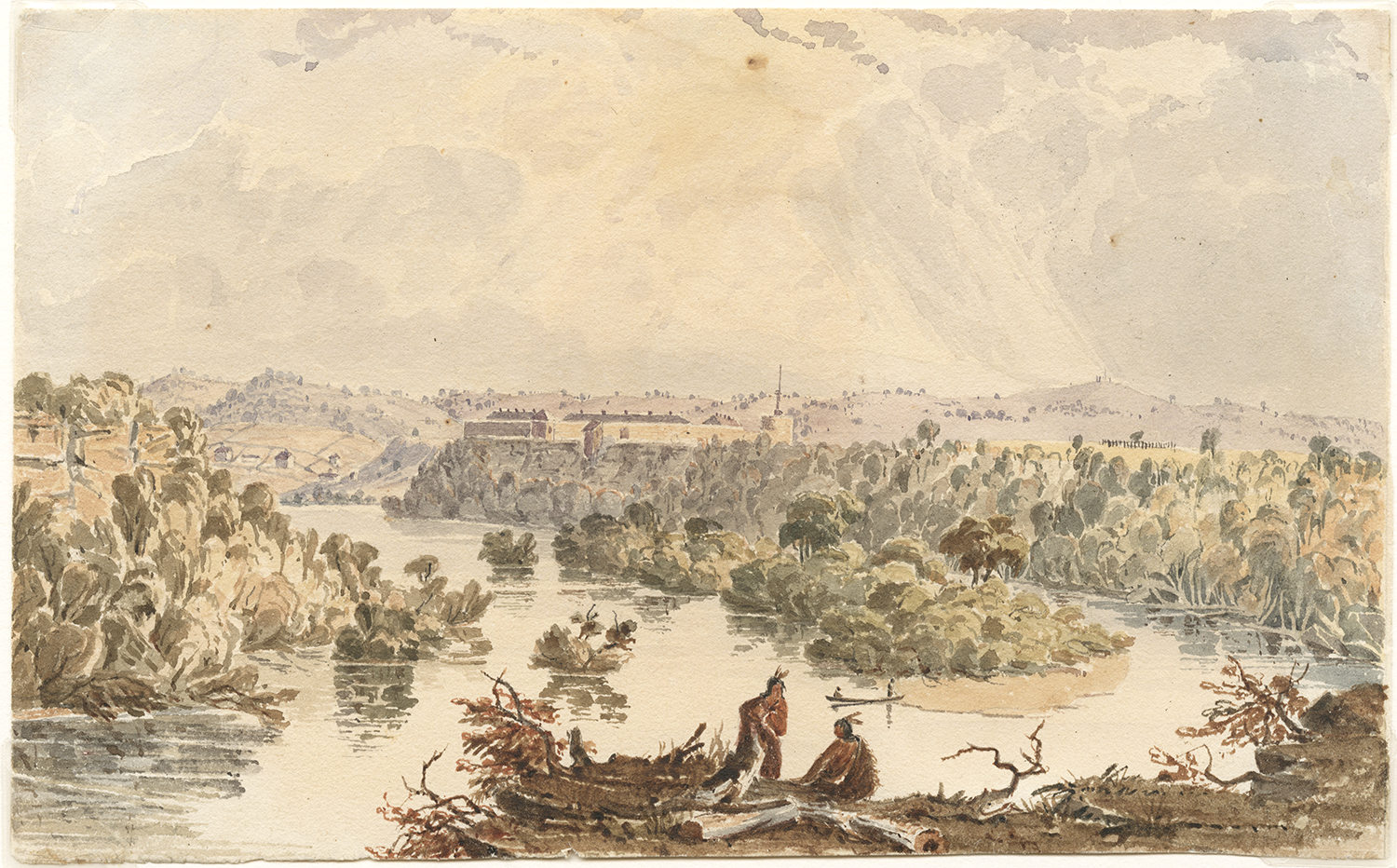

Distant View of Fort Snelling by Seth Eastman, 1847–1848 The image is sourced from the Minnesota Institute of Art’s online collection exhibit “Painting the Dakota: Seth Eastman at Fort Snelling.” No reproduction without permission.

Fort Snelling celebrates its bicentennial in 2020. It was built in 1820 by the U.S. Army to serve as a vantage point for monitoring threats to American interests in the fur trade. During autumn 2019, the Minnesota Historical Society (MHS) began construction of a $34.5 revitalization project guided by a vision statement titled “Many stories—still untold.”

Many questions are on my mind about Fort Snelling’s “revitalization.” What does it mean to tell stories about a place that doesn’t feel like it’s yours? Who gets to write and tell those “still untold” stories? How will the Historical Society determine which stories are the ones that need to be told in the here and now? And, as a site of important ecological as well as cultural relevance, how might those stories go ”deep time” and open up new vantage points on the site and its intertwined physical, material, and social histories. Writing a deep time story of Fort Snelling is an unenviable challenge. There are clear stakes in telling some stories, and not others, as well as telling stories in one way rather than another.

At the same time, Fort Snelling is a place so steeped in painful histories that it feels like only some people should have license to tell its stories; its Dakota stories, its black slave stories, its military stories. Yet, it is also one of our most public places, where families and schoolchildren come daily to learn about Minnesota’s early history—nearly everyone in Minnesota knows where Fort Snelling is and what they think it is all about.

I encounter Fort Snelling intimately and regularly. I bicycle near it on the river parkway. I glance puzzlingly at the stone tower nearly every time I cross the Highway 5 Fort Road Bridge over the Mississippi driving west. I hike through the Fort to cross the bridge that leads to Pike Island so I can pause at the confluence. Because of its everyday presence in my own life, I need to be reminded of its importance as a site of political conflagration over how we remember and reckon with to whom it belongs. I also never know where to start when I use stories to encapsulate the history of this place to my students, neighbors, friends, and family.

For example, take the story of the Wagon Train protest. In 2008, a Minnesota Statehood Sesquicentennial Wagon Train rolled its way toward Fort Snelling as part of a 100-mile, week long journey. In all, eighty-five people in period dress traveled by horseback in covered wagons, buggies, surreys, and one stagecoach. When they reached Fort Snelling, they were met with indigenous protestors who were drumming, burning sage, and carrying signs that read: “I am not invisible.” Some protesters laid on the ground in front of a squad car with a pair of signs reading: “If we get in your way” … “Will you kill us again?” Eventually, 13 different law enforcement vehicles arrived on the scene to carry away the disruptors.1 When you research stories about the Sesquicentennial Wagon Train, it takes some digging to find mention of the protests. Instead, most news stories revel in the fireworks and celebrity speeches that marked Minnesota’s hardscrabble Little House on the Prairie history.

A decade later, Fort Snelling is still a flashpoint of controversy. In May 2019, the signs that read “Fort Snelling Historic Site” were replaced with newer signs that read “Historic Fort Snelling at Bdote.” Now, those signs newer signs have been taken down because of public confusion. As part of the Fort’s revitalization project, the Historical Society has begun an official public process about renaming the site. The Minnesota state legislature would vote on any recommended renaming.

By contrast, the B’dote Memory Map is a living history of Dakota lands and culture. The project claims the Dakota occupied the land for nearly 10,000 years before the onset of settler colonialism in 1860, and they continue to exist. Through oral history plotted on the map, we learn why Fort Snelling is sacred land, and how the bluffs provide an ideal vantage point for seeing Wite Tanka (Pike Island) and the burial area that is now Pilot Knob. The memory map also tells the painful stories of Fort Snelling as the site of a Dakota concentration camp from 1862–63. Here, 1,700 people, primarily women, children, and elders, were imprisoned during the winter of 1862–63. For many Bdewakantunwan Dakota members, B’dote is the center of the earth for them, and as such it is now both a site of genesis and genocide.

I have been a Minnesota resident for fifteen years, and on most days I feel like a newcomer. Yet, I mostly feel comfortable teaching about the Mississippi River and its history. When it comes to Fort Snelling though, I shudder at the thought of attempting to represent all this site means. Part of my hesitation is that Fort Snelling deserves an Anthropocenic reckoning; a deep time analysis that layers human and non-human histories together.

It is meaningful that this Fort Snelling’s bicentennial renovation is called a “revitalization project.” Breathing life into the Fort means listening to its ghosts. The B’dote Memory Map provides some of these stories. A deep time history of the site could also juxtapose and intertwine many stories across time and space. It could render visible how slaves, including Harriet Robinson Scott and Dred Scott, may have interacted with Dakota peoples before, during, and after they were held in captivity at the Fort. The U.S. Supreme Court decided, 7-2, that the Scotts would remain enslaved in 1957. It is well known that this decision influenced the nomination of Abraham Lincoln—who opposed the Dred Scott decision—for the presidential election in 1860. Lincoln went on to sign the Homestead Act in 1862, creating the broader context for the Dakota War of 1862 and internment at Fort Snelling. What visions or nightmares of the United States of America did African-Americans and Dakota enslaved at Fort Snelling and beyond share?

Go even deeper in time and we can imagine stories of human and geological agency woven together. Native peoples have inhabited the region since the Ice Age ended. The petroglyphs in Wakan Tipi (Carver’s Cave), at modern day Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary, are interpreted to be a premodern planetarium. At the time those were drawn, St. Anthony Falls was located just outside Wakan Tipi in today’s downtown St. Paul. The waterfall scoured the sandstone and limestone bluffs, essentially eroding its way upriver to Minneapolis. When we talk deep time on the upper Mississippi, it is at once human and natural history. Fort Snelling then appears as an important and bloody chapter, but by far only a brief chapter in telling the stories of B’dote.

As the Historical Society reimagines the stories it will tell of and at the Fort, I look forward to growing into a different relationship with this place. As a resident of the river, however long my roots grow, I want a renewed experience not only when I visit the site but also when I think about representing its stories to others. I simply want to know more and know more deeply. Fort Snelling has much to teach us beyond canon firings and blacksmith demonstrations; it is the place where so much of the history that shapes our deeply fraught modern Minnesota experience begins.

B’dote is a Dakota word, meaning where two waters meet, that refers to the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The new signage raised the ire of many who argued this “revisionist” telling erases the military history of the site. This is not unlike the controversies about the renaming of Minneapolis’ Lake Calhoun as “Bde Maka Ska” by the Department of Natural Resources. David Kelliher, Director of Public Policy and Community Relations for the Minnesota Historical Society (MHS), told 5 Eyewitness News that Fort Snelling had not been renamed. Rather, he stated, “Lots of history has happened there over many generations. We want to tell all of those stories, and by telling those stories we absolutely are not diminishing military history or the contributions of veterans.”2

Distant View of Fort Snelling is a painting by Seth Eastman, an Army officer stationed at Fort Snelling, which tells a visual story of daily Dakota life during the brutal period of conquest and settlement.[1] Eastman painted a series between 1847–1855, and his paintings are often used by the MHS on their website. The bucolic scene of Dakota life near the Fort belies the cultural devastation being experienced at the time. These paintings tell not only different stories, but perhaps even fabricated ones.