Going Against the Flow

Commodity Flows seminar reflection

The Anthropocene River Campus seminar “Commodity Flows” immersed participants within a dense landscape of actual and historical commodity flows associated with the Mississippi Basin. In this reflection, Benjamin Steininger recounts how performative intervention, the mysterious “Bureau of Commodity Flows,” and engagement with local activists served as methods for disentangling the logistical complexity that helps to obscure the operations of these flows. In doing so, the links between the trade of Black bodies in Louisiana during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the local region’s contemporary petrochemical industry are underscored, as are the global connections of these streams. Through a consideration of the local effects of global dependencies, Steininger suggests, we can begin to reckon with—and change—our role in sustaining these flows.

What are commodities? And how do they circulate and flow, regionally and across the globe? And what can be learned about these issues from the exemplary Louisiana context, situated at the estuary of the Mississippi River Basin? Can this site provide one exemplification of how commodity flows have shaped and are shaping the epoch of the Anthropocene?

The Anthropocene River Campus seminar title “Commodity Flows” refers to two distinct concepts. The first term concerns the general commodity form of certain types of matter and material objects, while the second is about the circulation of these commodities. Both the commodity form and the flow of commodities, it is important to emphasize, are not natural occurrences but are rather technically produced. Neither a fruit on a field, nor a mineral in the ground is already a commodity by itself. A market is required to produce the commodity form. Only the potential to circulate, to flow, to change its place, and thus role, in an economic system turns an object or a material resource into a commodity. Conversely, the modes of transportation employed for certain goods are not arbitrary. Very specific substances and things provoke certain flows. The terms “commodity” and “flows” are not just linked but entangled with one another.

The geography of the Mississippi River system is, on the one hand, a natural flowing system of water, climatic zones, sediment, plants, and animals. On the other hand, this natural system of currents is a platform for highly artificial flows of commodities supplied and demanded by industry, which are moved by motorized transport. During the Commodity Flows seminar, we aimed to discuss and examine the questions and complexities these coexisting currents pose. We did so by putting ourselves into an exemplary landscape where those flows are present, beginning at ByWater Institute of Tulane University directly on the banks of the Mississippi in New Orleans and from there traveling through the alluvial landscape of Louisiana. Utilizing a variety of methods—including plenary discussions along with smaller group work to discuss concrete commodities and explore maps of their flows, plus artistic and performative interventions—we aimed to translate some aspects of what is present in this geography, be it actual or historical, technical or social, obvious or hidden, into our academic, artistic, and activist discourse. Seminar trips included a visit to the Whitney Plantation, today a museum that tells the histories of those who were enslaved there, a visit to one of the biggest fertilizer plants on the planet, situated in the small town of Donaldsonville, and journey through the industrial corridor near St. James Parish, commonly referred to as “Cancer Alley”, to engage with local activists and policymakers. Through these journeys, we immersed ourselves within the disturbingly dense landscape of actual and historical commodity flows.

Fertilizers, addiction, and ammunition

At the start of our first day at the ByWater Center, after the introductory and organizational remarks had concluded, seminar participants unknowingly encountered the first performative intervention into the “expected” flow of the seminar itself. A woman began to speak in a raised voice: “I’m a pharmacist. I graduated from Purdue University in Lafayette, Indiana and worked as a pharmacist for an independent store for five years.” And the flow of her words didn’t stop. It took a while to understand that a performance had started, something which became apparent when two other actors joined in with their own monologues, all of which were based on a text by Chicago artists Beate Geissler and Oliver Sann. The “pharmacist” was complemented by an “addict” and a “historian.” What bound these three together was the flow of nitrogen through modern life and history. Fertilizers, addiction, and ammunition—if chemical elements were actors, nitrogen would be cast as the hero of a tragedy. And there were very real tragedies to report, such as the story of Clara Immerwahr, a pacifist and the first female chemist with a PhD in Germany, as the historian explained. Her husband Fritz Haber was one of the key figures of nitrogen fixation in ammonia, and one of the leading chemists during the First World War. Haber’s commitment to the development of poison gas drove Immerwahr to suicide in 1915, we learned, while his work on ammonia synthesis was awarded the 1918 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Without the possibility of producing ammonia synthetically for ammunition, the First World War, and the scale of its death toll, would not have been possible. But since the substance is also crucial for fertilizers, neither would it be possible to feed the world’s population of the twentieth century without it. And the bitter lessons ammonia has to offer do not lie solely in the past. The enslavement of significant strata of the US population by methamphetamines is linked to the chemistry of ammonia, as was made clear by the character of the addict.

There are no simple stories with commodities, and the tone of the performance carried us back into reality as the seminar continued. The most obvious “functional” operation of the Mississippi River system is as a gigantic transport system. It is in fact the biggest system of inland navigation in the world, with direct access to all the world’s oceans and to numerous agricultural and industrial areas in North America. From where it meets the Gulf to the Exxon Refinery located a little further upriver at Baton Rouge, it is dredged by the US Army Corps of Engineers to enable ocean-going freighters with a draught of up to 13 meters to travel down it. If there is any “commodity flow” that can be easily observed with the naked eye, then it can be seen here in New Orleans, where all those waterways come together. So, it was fitting that the next step of the seminar was a boat tour of the Port of New Orleans.

What we saw in the Port pointed to a geography that extends far beyond the immediate surroundings. Container ships were scarce; and what we saw filling huge push-pull ‘tow’ convoys up to 450 meters long were agricultural or chemical products in open barges. If this experience of the commodity flows passing by in the port was in any way representative, it would suggest that the USA’s Midwest, the area that is connected to this port by the Mississippi, primarily produces raw materials and hardly any manufactured goods.

Through this same act of observation, another dimension of flows became tangible. The unfamiliar and somewhat discordant sound of a steam-driven calliope organ from one of the historical steamships in the port made it clear that every mechanism of a flow of goods is contemporary while also being embedded in a historical flow. What now passes through the port of New Orleans is the effect of what has been transported and transformed through Louisiana’s process landscape for centuries.

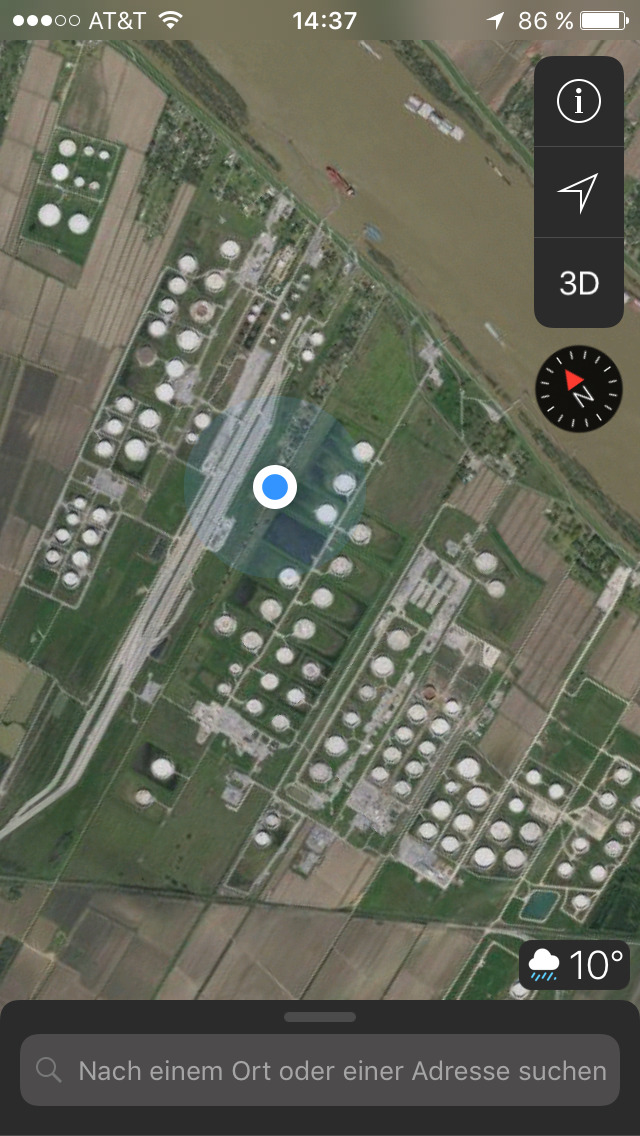

Transportation is only one function of the mass of water below that was below our tour boat. When it enters, the water that flows into the port at 15,000 cubic meters per second has just passed one of the biggest chemical industrial areas in the world. In this “petrochemical corridor” between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, the river provides the chemical raw material H2O, which is used for cooling processes and steam production in the various facilities lining the banks. The flow of water is here combined with another flow system. Situated at right angles to the flow of water are flows of oil and gas. Louisiana itself has significant oil deposits, which lie in the immediate vicinity of the delta and in an abundance offshore in the Gulf of Mexico. To this end, a confusingly dense network of pipelines crisscrosses and follows the river. Plantation, Dixie, Coastal, and Colonial, some of the most familiar names, are just a few of the pipelines linking the region with onshore and offshore oil fields between the Gulf, Texas, Oklahoma, Dakota, and Alberta. As barges come down river full of raw agricultural goods, the products of the chemical plants go back upriver to power the industrial agriculture of the Midwest, including fertilizers such as Fritz Haber’s ammonia as well as pesticides. But much of this chemical soup returns, since the Mississippi also serves as an official and unofficial transport route for erosion and nutrient-enriched wastewater.

Introducing the Bureau of Commodity Flows

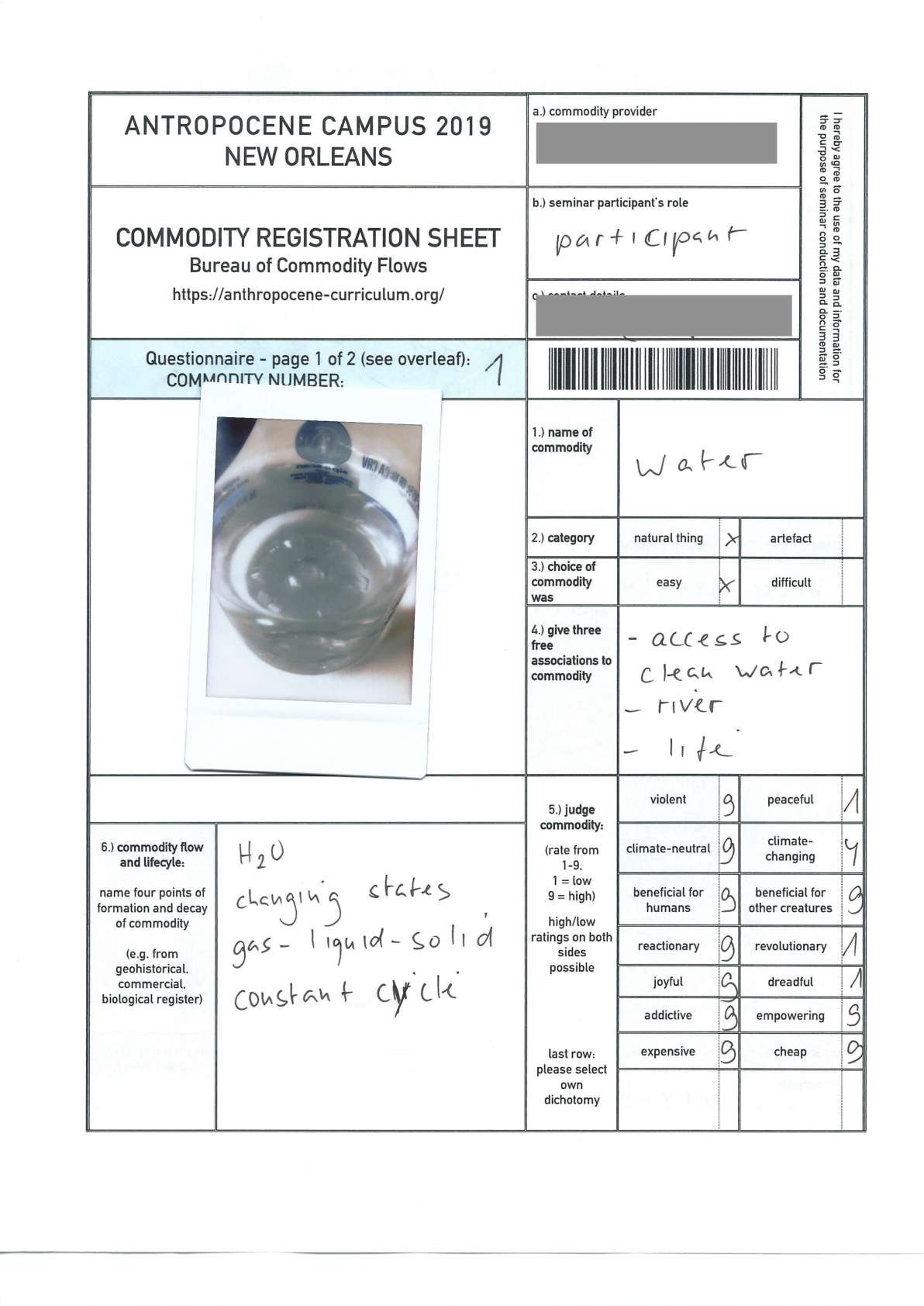

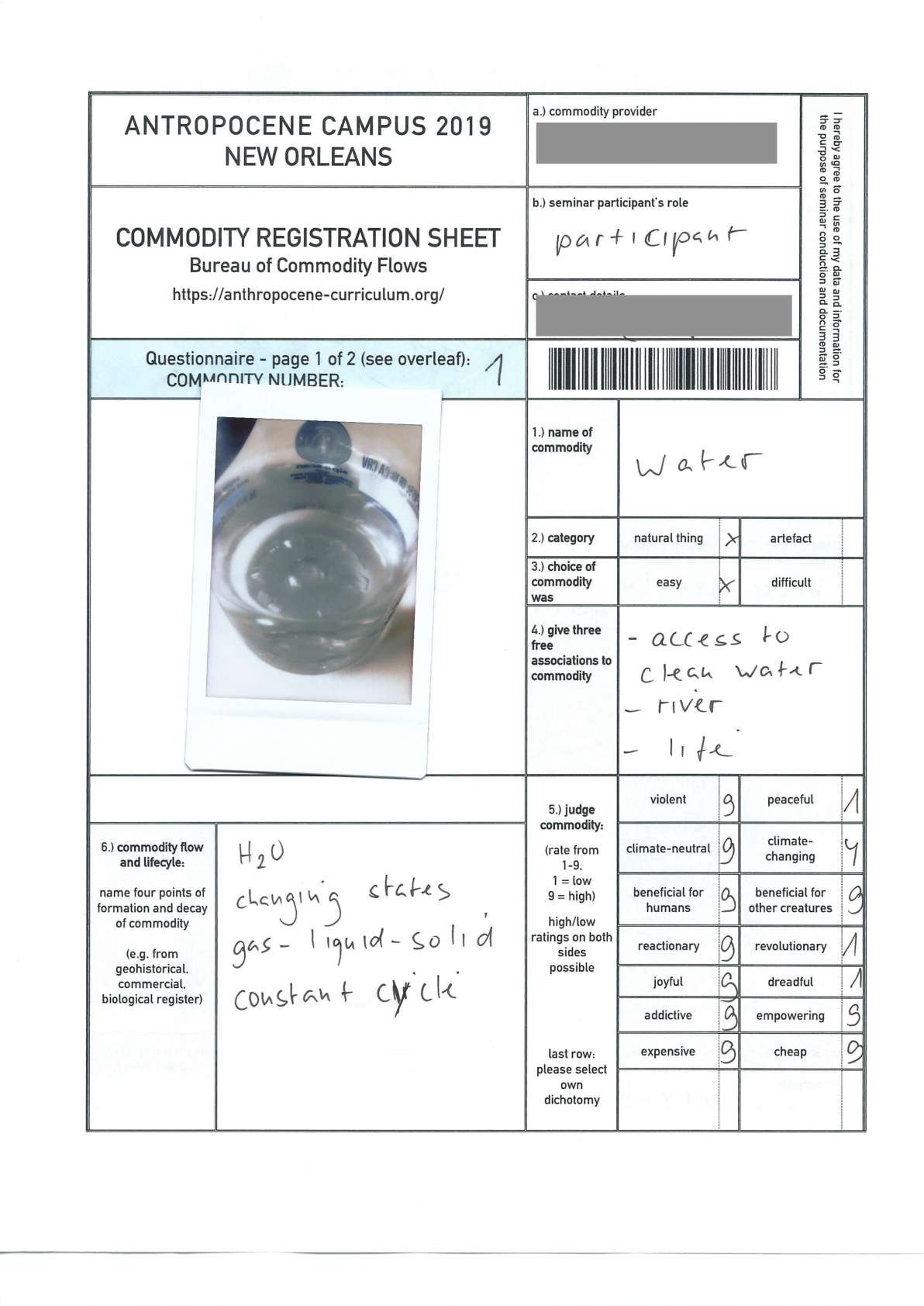

After the tour of the port, with impressions of flowing waters and ships fresh in our minds, we returned to ByWater Institute. As a condition of participation in the seminar, everyone had been asked to bring a commodity to the session and now it was time to compile and discuss them. However, in order to let the chosen objects and substances talk to each other and to us, to find out why they are commodities in the first place and how they relate to other commodities, it is was not enough to simply “bring them along.” After all, no commodity is simply brought on a ship or delivered to a factory or to a customer without the workings of another crucial element: bureaucracy. Accordingly, an employee of the fictitious “Bureau of Commodity Flows” was also present during the seminar to supervise and explain the filling in of the forms required to accompany each commodity, and to ensure that correct administrative procedure were adhered to.

Seminar participants were asked to bring a commodity to the seminar session, which the Bureau of Commodity Flows then required them to "register."

Download Full PDF (82 Pages)The eighty pages of forms that resulted and are presented here provide information about the range of things cataloged by the Bureau that day—and the way in which they were recorded. For the Bureau’s forms do not look like a standard logistics transport label. Instead, these forms evidence an interest in the lifecycle of goods that few companies can be said to possess and the set of categories queried—violent vs. peaceful, addictive vs. empowering, joyful vs. dreadful, reactionary vs. revolutionary—do not originate from the realm of haulage so much as that of human subjectivity.

The performing of such an exercise was obviously a distortion of what is typically understood as a “smooth” flow of goods. Just as we got started, we found ourselves faltering. It is tiresome to fill out the forms, not to mention annoying to have to appear as part of the form yourself. Some participants simply refuse to give names or contact details, others willingly give their telephone numbers and data— themselves prime commodities in the age of digital capitalism.

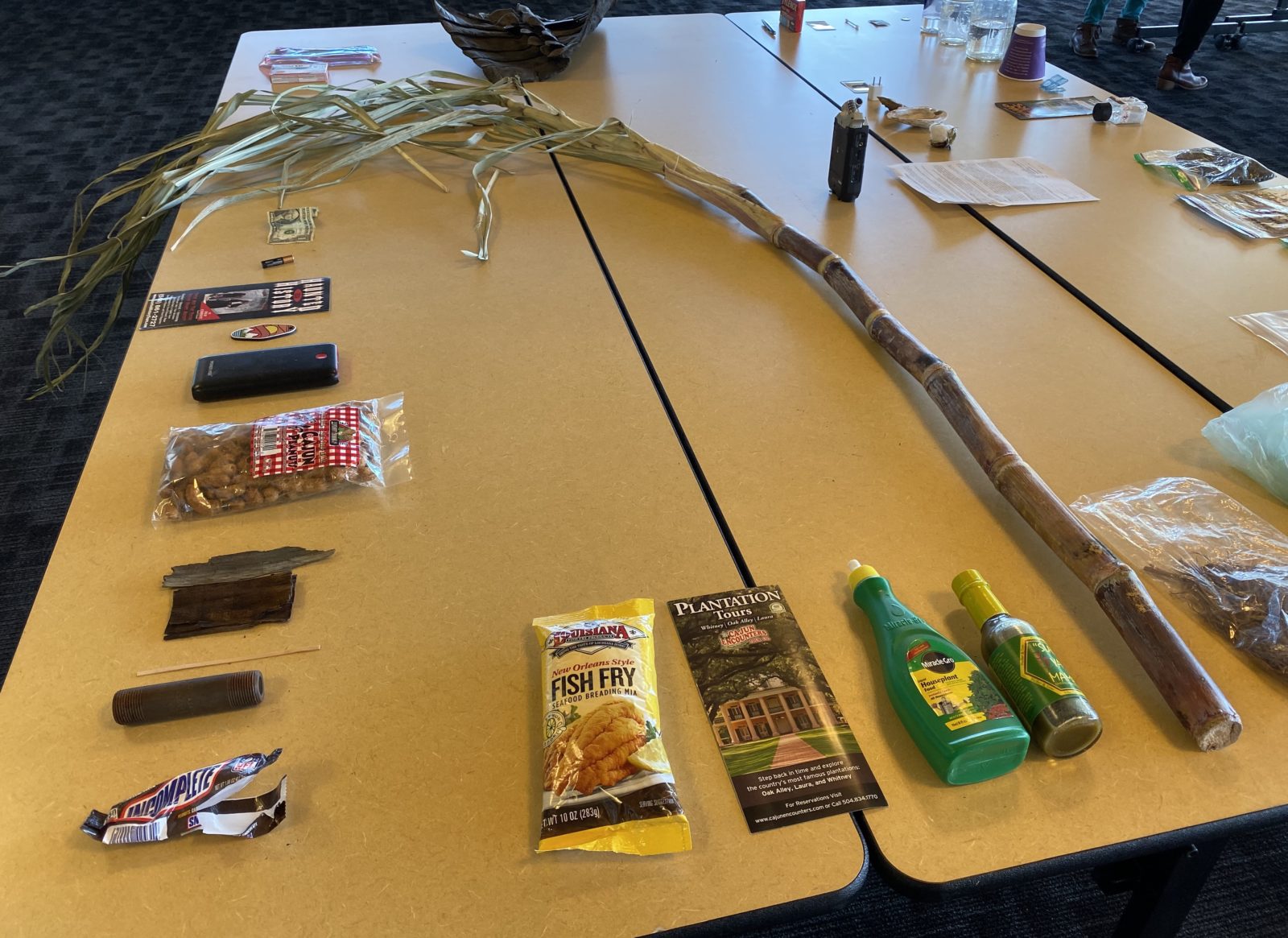

With forms (more or less) completed, the next step was to use the commodities to talk with each other in small groups, with each provider was asked to introduce their particular commodity. So what ended up on the tables once the paperwork procedure was over? The commodities, in order of appearance and described using the name they were given by their respective commodity provider, were as follows:

Water / Chaco brand shoe / Wind turbine blades / PVC (in bag and box form) / Alligator / Top soil / Sugarcane bagasse / Ethylene glycol / Turpentine / Insurance / Keys to a house in New Orleans / Soybeans / Mississippi River water / Southern Fried Cajun Peanuts / Mississippi River sediment / Pencil / King cotton / Hard white winter wheat / Phosphorus / Frac sand / Ibuprofen / Corn flour / Wax lined paper cup / Neoprene, chloroprene / Q-tip / History / Battery / Alligator / Phenol / Walker and Sons “slap your mama” green pepper sauce / Wooden stick / U.S. currency / Charging adaptor / Broken keychain trinket / Freshwater mussel / Truth wrap / Polyvinyl chloride PVC / Timber / Black body / Polyethylene pellets (“nurdles”) / Cotton in the form of a shirt.

The commodities are sorted and laid out, with the sugar cane needing the most table space. Photo by Neli Wagner

A museum of the present could consider itself lucky to have this “excerpt” of the world among its collection: an array of animal, vegetable, mineral, human, agricultural, and chemical goods—which together form a network of different functional contexts. For none of these goods stands for itself: Water is constitutive of almost everything, while the commodity “human,” which one participant brought to the seminar in the form of himself, has to do with almost all other goods in existence. Through the sugar cane specimen—the longest commodity on display—a connection is made between slavery and the chemical industry in Louisiana, the same context from which many of the substances on the tables originate.

During the exercise, we could explore just some of the interrelationships of these exemplary commodities, as only five or six goods or things per group entered into conversation with their human companions. In a further step though, we followed up on selected substances or groups of goods on regional and global maps compiled and presented by the urbanist Nikos Katsikis. To track these, Nikos’ presentation and maps made use of the digital data stream that accompanies the flow of goods. Just as the paperwork at the Bureau of Commodity Flows made explicit, digital data collated by the Federal government acts as a second-order flow to make the flow of commodities possible. Similarly, in the real world of logistics, only a good accompanied by paper or data is a “good” good. As a side effect of these data flows, the geographic movement profiles of all the transported and industrially transformed goods can generate graphs that can then be translated into maps. What we discussed in our groups at our tables with our maps was mirrored outside the window of the ByWater Institute, a network of interconnected streams, current and historical.

Population density in white gradient, and the Mississippi river watershed in orange. Map by Nikos Katsikis Distribution of the agricultural production areas of major crops across the Mississippi basin. Map by Nikos Katsikis Volumes of road and waterborne freight transport across the Mississippi basin. Map by Nikos Katsikis

The legacy of human commodity flows

Against this backdrop, it was clear that a seminar on commodity flows would be of little value without setting itself in motion once again. On the second day of activities, our first destination was the former Whitney Plantation, near Wallace, in St. John the Baptist Parish on the Mississippi River Road. The Whitney Plantation is one of the very few former plantations in the USA—and the only one in Louisiana—that is entirely dedicated to recounting the history of slavery and thus honoring to the memory of the people who for centuries were degraded through the trade of Black human bodies as commodities.

Unlike other plantation museums, at the Whitney Plantation a focus upon white slave owners and their families is avoided. Instead, visitors to the former plantation manor house only enter those rooms in which the enslaved lived and worked in. The insights the seminar group received at this museum and memorial, from its research director Dr. Ibrahim Seck, were shocking. The everyday reality of those who were enslaved was brutal. They served under owners who did not shrink from rape as a means of both terror and of increasing the number of slaves they owned, and increasing their commodification. Similarly shocking is the ignorance with which contemporary US society confronts this heritage. As seminar participants from Louisiana reported, monuments to Confederate generals can only be dismantled under the protection of snipers, and the question of reparations for the families of the formerly enslaved is not even considered by Federal and State authorities.

During our visit, it became clear that sites like the Whitney Plantation are where the foundations of all current flows of goods in the Mississippi system were laid. The assets accumulated here were once the cornerstone of the North American economy. Until well into the nineteenth century, more US capital was invested in the slave trade than in technology, as one of the participants of the seminar explained. And it is these same flows that led to the onset of the Anthropocene, with human technological activities become perceptible at a planetary scale arguably for the first time. The shipping of hundreds of thousands of people from countries like now Senegal or Gambia from Western Africa to the American continent to be used as human machines to cultivate a crop that originally came from Asia, to supply a world market with concentrated chemical energy in the form of glucose, can only be understood in such planetary terms.

Following the money—and knowledge

The seminar’s next destination took us from the stories of those who were abused as “fuel” in a conveyor belt of planetary energy flows during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, to those now suffering the effects of living alongside the facilities producing chemical fuels in the twentieth century in the very same region: Donaldsville, home to the largest fertilizer factory in the USA. What had seemed like something distant and to past history during the performance of the first day of the seminar—the Haber-Bosch-process—is very present and real here.

The plant makes use of nitrate chemistry, which is at the center of the process that bonds nitrogen from the atmosphere to hydrogen, currently produced from natural gas through catalysis to produce ammonia (NH3). In Louisiana this is integrated within one of the largest petrochemical production complexes on the planet. For 100 miles between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, one encounters refinery after refinery, chemical plant after chemical plant: Exxon, BASF, Shell, Rubicon, Praxair, Air Liquide, Formosa, Shintech, Mexichem, Poly One, Mosaic, CF Industries, Chevron, Sid Richardson, Epsilon, Marathon, Nalco, Colonial Sugar, Witco, DSM Polymer, and countless more.

The Baton Rough Refinery is one of dozens found along the stretch of Mississippi between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. Photo from Wikicommons, CC-BY-SA2.0

Companies from all around the globe, from the US, Asia, and Europe produce here. In particular German companies such as BASF have left traces, not at least by the history of German chemical industry. Already in the eighteenth century, the region was called “German Coast” on account of the number of German settlers and plantations and the industrial history around towns with German names, such as Geismar, Essen, and Siegen, adds more to that story. After the invention of the Haber-Bosch process around 1910 at BASF, hydrocarbons also became a subject for German chemists. Coal was planned to be transformed into liquid fuel, but the project turned out to be more complex and expensive than expected, with potential benefits for not only the coal industry but also oil companies.

As a result, at the end of the 1920s, US-oil companies such as Standard Oil of New Jersey and German chemistry such as I.G. Farben started a formal cooperation. Shared laboratories were established in Baton Rouge, and a new hydrocarbon chemistry was developed to produce fuel in the years before the two countries found themselves at war. This historical flow of knowledge and money needs to be taken into account to understand the industrial landscape at the Mississippi and its present role for global commodity flows. What is processed here today is part of a historical process, and it was the historical process that shaped infrastructures that would transform commodities in an unprecedented way.

From molecular mobilization to machine mobilization

Through this chemical history, commodity flows are therefore not only recognizable as the geographical shift of substances, but also in the form of internal, chemical mobilization. In the pipeline systems and reactors of chemical plants, substances are both on the move and in transformation, so that dynamics can be set in motion at other locations, up- and downstream. The main product of the plant in Donaldsonville, fertilizer, is one of the best examples of this. Fertilizers are chemical substances, but it is the biosphere, where they set growth in motion. As such, they have effects on the regional but also on the planetary biosphere and its material flows of the Anthropocene. They are transported in huge ships from Louisiana to the soya and corn steppes in the Midwest, but thanks to erosion, a large proportion of the chemicals flows right back past the plants where they originated, eventually leading to algae blooms in the Gulf of Mexico and the creation of oxygen-free “dead zones.”

What we saw from behind the fence of the plant and as tried to understand these interlinking flows is representative of the molecular-planetary industry as a whole. It is through the same form of technology, of the kind that rules the fertilizer plant at Donaldsonville and the petrochemical corridor, developed at the beginning of the twentieth century, that the geography of the planet and flows within the biosphere and the sphere of human technology as a whole have changed. It is only through this type of molecular mobilization that the machine powered mobilization of commodity flows—in freighters, trucks, and planes—has become possible. It was only with this technical chemical energy regime that the Great Acceleration of the twentieth century was possible: population growth, global exchange, global economic growth—and with it all the commodity flows that we understand as typical of the Anthropocene.

And here we were able to connect the industrial chemical sphere of the twentieth century with the brutal plantation sphere that we learned about just before at Whitney. There is no way to think about the one ignoring the other, since today’s industrial infrastructure occupies the same sites (the packages of land along the river) as former plantations. Today, not even the masters of those plantations, in their palace-like houses and with all the workforce they abused, commanded the powers that we as ordinary car owners are used to in the form of fossil horsepower. In fact, none of those who participated at the seminar, regardless of which continent they traveled from to New Orleans, live a life that does not, in part, depend upon petrochemistry. Motor fuels, aspirin, superglue, Gore-Tex, artificially fertilized food—the list of commodities that intersect with petrochemistry appears almost endless.

The local effects of global dependencies

In the context of commodity flows, “addiction” as one of the topics of the lecture performance of the first day refers not just to a pharmacological issue affecting individuals. It is also an apt way of describing the era of late capitalism, a modus operandi that only “works” when it has access to a constantly increasing input of increasingly complex substances. Traveling through the petrochemical corridor, we learned a lot about the concrete, ecological, but also social consequences of this lifestyle. The condition of the consumer of commodity flows as an addict is one way to problematize these flows. But by traveling to the petrochemical corridor, we were able to go even further and observe the problems caused not only for consumers but for the communities where the production of these chemicals happens.

Scott Eustis, Community Science Director of Healthy Gulf, joined us for this endeavor and presented the work of his organization to fight the problems of pollution and associated issues environmental justice. On the ground, the situation didn’t require a flipchart or a projector—the view through the bus windows, of countless facilities belching out white plumes of toxic smoke and accreted mounds of bright yellow sulfur, towering over the small communities sandwiched in between, told us everything we needed to know. Thanks to his in-depth knowledge of the region and the issues affecting it, Scott was able to organize meetings with a local activist and a councilman. The activist was Travis London, a young mayoral candidate who we met in Donaldsonville, while on a second stop at a small stretch of residential homes nestled between large storage facilities for oil and petrochemical products, we met Councilman Clyde Cooper from St. James Parish.

Through these meetings, one could see how much courage, wisdom, and pragmatism is needed to manage communities in this region. It remains to be seen whether the planetary perspective should become the guiding principle for all local decisions, or whether much would already be gained if the simple laws of the state, such as those governing the taxation of corporate profits or environmental guidelines, were followed before starting to discuss planetary legislation.

What we learned from Clyde and Travis was something like the antithesis to the famous 1930s slogan of the chemical company DuPont: “Better Things for Better Living… Through Chemistry.” Such a promise—that the petro-modern age would grant freedom, that a better life is possible with fuels, pharmaceuticals, and plastics—rings hollow in Louisiana’s petrochemical corridor today. The subject takes on an even more disturbing dimension when one considers that it is at places like this, in an area where people have few choices, commonly referred to as “Cancer Alley,” and the Trump administration’s Department of Energy has now branded hydrocarbons as “freedom molecules”.

Flow interventions

Real answers to what we faced in the petrochemical corridor would be a tough goal for a two-day traveling seminar. But we had done our best with the academic and artistic toolbox at our disposal to keep at least our questions as complex as they need to be here and to connect with the flows of various commodities, in their present and their historical incarnations, as real things we “processed” at the “Bureau of Commodity Flows”, as data at the mapping session, as the subject of a moving performance, and as products of a vast industrial district that can be visited as a disaster tourism monstrosity but which is also as an area of human life and work for thousands of people.

St. James Parish, Louisiana. A small strip of homes can be seen between the storage tanks. Field Note by Benjamin Steiniger

On the same small strip of mobile homes and modest houses in St. James Parish where we met Clyde—wedged between waste oil storage facilities and loading stations, and thus at the center of all the challenges our seminar was attempting to deal with, where the historical burden of centuries of the enslavement of people is combined with the modern dependence on petrochemicals that are as vital as they are harmful—that the seminar witnessed arguably one of its most significant moments.

The academic discussion of the Anthropocene and commodity flows became a mere backdrop, as our bus driver Thomas entered into conversation with Clyde and Travis. After a whole day of driving our group with visiting seminar participants through the area, Thomas shared his experiences as Louisiana local. He described the challenges that come with living in the surrounding polluted neighborhoods, where people try to grow vegetables on the poisoned ground of former landfill sites, where petrochemical profit has almost been habitually placed above the wellbeing of residents. Once again, the flow of words, which went back and forth between Thomas and the two politicians, didn’t stop. But unlike the performance of the first day, this time the flow was not the result of any intervention curated by the organizers; it was the reality of the region itself, one dramatically shaped—and deeply scarred—by commodity flows, that intervened into our seminar.