Layers of Violence

The Cancer Alley Anthropocene

In the age of the Anthropocene, the neat sectioning off of historical periods, punctuated by short, sharp shocks in the form of disaster “events” obscures not only a longer view of history but also the often very slowly unfolding and interlinked disasters that have engendered the current era. For example, the contemporary petrochemical industry in Louisiana today occupies the same footprint along the banks of the Mississippi River that was once filled by plantations where enslaved people suffered under a brutal regime of forced labor. In this essay, Scott Knowles, Professor of History at Drexel University whose work focuses on the history of disaster worldwide, and Ashley Rogers, Executive Director of the Whitney Plantation Museum in Louisiana, unfold and critically examine this Anthropocenic space characterized by a long history of extraction, and call attention to the many untold stories underneath these layers of violence.

On January 8, 1811, the largest uprising of enslaved people in the history of the United States began on the Mississippi River plantations along the so-called German Coast of southern Louisiana. Inspired by the revolution in Haiti, which overthrew the slave power in 1804, almost 500 slaves participated, before being met and defeated by federal forces and local militia two days later, near present-day Kenner, Louisiana. Over the course of the revolt, two white men were killed. After summary trials, ninety-five of the slaves faced execution and decapitation, their heads posted on pikes stretching along the path of the revolt. It was a disaster that overwhelmed the local population as surely as any hurricane or epidemic. But suppression of this history was crucial to slave owners, who were desperate to keep their captives illiterate, ill informed, and isolated. And so, the German Coast Uprising remained mostly a local story, fading into near legend. It has not been widely taught or studied, and barely exists in American history textbooks.

In November 2019, the performance artist and activist Dread Scott led a reenactment march to commemorate the uprising, and to inspire awareness of the connection between that distant history and our own time. The reenactment coincided with the opening of the Anthropocene River Campus, a multiday exploration of the Anthropocene, history, and environmental justice based in New Orleans and organized by the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin in partnership with The New Orleans Center for the Gulf South at Tulane University.

Historiography has generally treated the historical eras of southern Louisiana as separate entities, marked by dividing lines such as the opening of colonial settlement, the founding of the United States, the end of the Civil War. But in an anthropocenic frame of mind, we need to take a much longer historical view, and we now see socioeconomic systems that were previously analyzed separately in the same frame: intensive, extractive plantation capitalism; unfree and unhealthy labor; structured violence and inequality—from the slave system of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, to the Jim Crow system of racialized labor after 1865, to the industrial system of petrochemical production in the current era. The flow from system to system forms a remarkable anthropocenic continuity.

Not only were South Louisiana slaveowners successful in their suppression of the German Coast Uprising and its history, but they thrived in the decades that followed. After the United States’ participation in the international slave trade came to an end in 1808, Louisiana became the heart of the domestic slave trade in the Deep South. Investors and speculators streamed south, buying land to plant with cotton and sugarcane and slaves to work it. Propped up by a tariff on foreign sugar, Louisiana sugar planters expanded their holdings of land that hugged the river between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. They grew phenomenally wealthy off slave labor, building ever more opulent and fantastical plantation homes to showcase their success. These homes sat facing the levee one after another, each one with attendant, orderly rows of slave cabins crammed with dozens of enslaved workers.

Louisiana’s sugar plantations had some of the highest populations of enslaved people anywhere in the country. The stately homes, set off by lush gardens and stands of oak and pecan trees, obscured and softened the industrial-scale labor and violence in the fields and sugar factories. Mark Twain famously wrote in 1883 that Louisiana’s plantation homes on either side of the river sat “so close together, for long distances, that the broad river lying between the two rows, becomes a sort of spacious street.”1 By the time that Edmond Bozonier Marmillion, a prominent Louisiana planter, began building his fanciful San Francisco Plantation in the 1850s, the great slave revolt of 1811 must have felt to the community like a long-distant memory—sugar planters were wealthier than ever, their success resting on the brutal, violent control of enslaved workers.

San Francisco Plantation is now a major tourist destination in the middle of what is known as New Orleans Plantation Country. Tourists from around the world come to southern Louisiana to experience the culture, food, and history of this once wealthy slave society. As with many plantation museums, the slave owner’s home is the prize of San Francisco Plantation. The big house, with its ornate facade painted in rich Caribbean blues and yellows, is prominently featured in regional promotional materials and advertisements. A visitor might be forgiven for being captivated by this spectacle of Antebellum architecture—that was the very purpose of its construction, after all. But it’s hard to see the complex truth with your gaze fixed, myopically, on the house. Widening the scope reveals the architectural context of this 1853 mansion. It is surrounded today on all sides by petrochemical tanks and machinery belonging to the Marathon Oil Company, which owns and operates the museum. Beside, behind, throughout the property there are ugly, unsettling reminders of the economic imperative for the home’s existence: in the nineteenth century, agricultural slavery; in the twentieth, petroleum.

San Francisco Plantation, which was at one time known as Saint-Frusquin, is rare in how well documented it is as a site of violence. After Edmond Bozonier Marmillion died in 1856, his son Valsin Bozonier Marmillion took over the plantation. Multiple sources confirm the conditions enslaved people endured under Valsin’s ownership. “The cruelest master in St. John the Baptist Parish during the time of slavery was Mr. Valsin Mermillion,” recalled Mrs. Webb, a woman who had been formerly enslaved by Marmillion. “One of his cruelties was if a slave was disobedient, to put him standing in a box with nails in it, and make him stand in a way that he could not move and could not swat the flies and ants that crawled on him.”2 Marmillion seemed to relish the ownership of his human chattel, so much so that he burned his own initials into their flesh. During the Civil War in 1864, out of Marmillion’s 210 enslaved laborers, 205 fled the plantation to Union lines.3 Of those, thirty had been branded with the initials “V.B.M.”—most on their chests and shoulders, but some on their foreheads.4

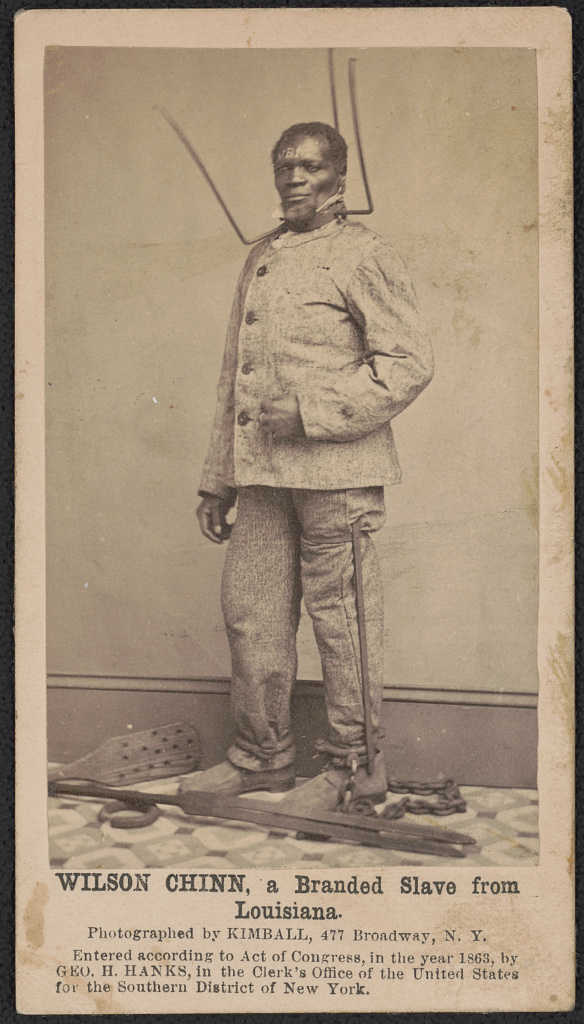

Marmillion’s practice of branding his enslaved workers became widely-known during the war. One man who was enslaved at San Francisco Plantation, Wilson Chinn, sat for photographs along with several other Louisiana freedpeople. In Chinn’s portrait, he demonstrated the instruments of plantation torture, including leg irons and a bell collar. Keloids forming the initials of his former owner can be plainly seen across his forehead, a gruesome reminder of the violence that enslaved people endured. This photo, commissioned by Union Colonel George Hanks and sold as a cartes-de-visite to raise funds for schools, remains one of the most famous images of an enslaved person in the United States.

Wilson Chinn, branded with the initials of his owner, Volsey B. Marmillion, wearing a punishment collar and posing with other equipment used to punish enslaved people. Photograph from Library of Congress, public domain

Marmillion was deeply committed to recovering the property he lost during the Civil War—namely, the 205 enslaved people who fled to freedom. After the River Parishes came under Union control during the Civil War, Marmillion “took the oath of allegiance, but refused to work his plantation unless he could have his own negroes returned to him.”5 Many of Marmillion’s formerly enslaved laborers were nearby, working in Union encampments in New Orleans. When a Union official attempted to get them to return to work the plantation, they all refused to return. “I will go anywhere else to work,” one man said, “but you may shoot me before I will return to the old plantation.”6

Historical scale is crucial to discussions of the Anthropocene, and so too is an understanding of the ways that disasters like a slave revolt, or Hurricane Katrina, or the Deepwater Horizon oil spill gather and hoard attention to the exclusion of slower and steadier processes of wealth making, and of violence. Strong economic and political forces are at work in the portrayal of a slave revolt or an oil spill as an aberrant event, unconnected from the normal flow of time, somehow separate and operating according to the logics of chance, or acts of God, or the madness of men. The idea of a “slow disaster” is a way to expose and explore these political investments in “event thinking,” and an invitation to think about disasters not as atomized events but as long-term processes linked across time—a crucial analytical act for the Anthropocene. Sometimes the linkages are documentable through the pages and photographs of a violent plantation era, sometimes they are buried more deeply in the land, the archaeological record, and at others aloft in the atmosphere.

The plantations needed river access to move their sugar cane to market—a global market that was intensifying over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries through industrial-scale plantation agriculture and the brutal “management” of slave-labor forces. The plantations marked out long, skinny plots of land, with majestic houses usually fronting the river, today hidden behind the Mississippi River levee system. Docks and refining works stood along the river, slave houses stretched back into the cane fields, and swampy woods made up the rear. After the Civil War—the moment of an expected liberation for the freed population of the German Coast—the economy carried on largely unchanged, with sons and daughters of enslaved people, and grandsons and granddaughters, working the land. They were tied to this land by Jim Crow laws that prevented free movement and locked African Americans in debt, unrepresented and in constant fear of racial terrorism.

In the early twentieth century, the land use began to change. Oil was discovered at Beaumont, Texas, in 1901, which was quickly followed by discoveries in Louisiana in 1906. Standard Oil bought a 300-acre cotton plantation outside Baton Rouge in 1909, establishing a precedent for dozens of companies. Chemical manufacturing to serve markets for fertilizers, pesticides, plastics, and the manifold additives for petroleum manufacture settled in to stay. The long, skinny plantation holdings were now assembled for industrial uses—perfectly situated for the purposes of petrochemical manufacturing with their river access points, once again tying the land and the factories to a toxic global market. As international companies bought up Louisiana’s sugar and cotton lands, refineries, tank farms, and pipelines began to share space with plantations, many of which did not cease operations until the late twentieth century. The intensification of petrochemical manufacturing along this stretch of river delta is heralded as one of the defining features of American economic development through and following the Second World War. Environmental impacts—manifest in the air, the water, the senses of the residents and workers—were ignored in the absence of any regulations or restraint. Sugarcane still grows along the edges of the industrial plants, and cattle graze along the fence lines.

St John the Baptist Parish near the DuPont Denka factory. Field Note by Scott Gabriel Knowles

In the newly opened plants, workers were (and continue to be) mostly white, and skilled positions for college graduates are plentiful. The neighborhoods surrounding the plants are largely African American communities, made up of the descendants of the sugarcane slavery system. Their communities have become sacrifice zones, rained on by the pollutants emitted night and day by the plants. In LaPlace, for example, the manufacture of plastics at the Denka Performance Elastomer plant has resulted in chloroprene emissions that are tied to cancer, skin conditions, dizziness, and headaches. Today residents of LaPlace, Reserve, and Garyville are fighting to enhance air-quality monitoring, and to find the funds to move an elementary school that sits on the Denka fence line. Continuous agitation from community members, supported by environmental chemist Wilma Subra and the Louisiana Environmental Action Network, has led to some hope for the school’s relocation, but no hope that the plant will close. Pollution is the violence of everyday life in LaPlace.

The Denka plant is four miles from the San Francisco Plantation. The people being poisoned in the immediate “sacrifice zone” of Denka are the descendants of people who Marmillion branded, chained, and stuffed into boxes. The violence exacted upon the bodies of enslaved workers was visible. Welts, abrasions, and scars told a story of profit extracted through brutality. Today, their descendants suffer a violence that is almost invisible. It is in the air they breathe, the water they drink—their rates of COVID-19 infection are even higher than the American average—and chronic health struggles predispose them to greater suffering today. Like their ancestors, their bodies suffer for the generation of someone else’s wealth. The only industries that have ever existed on this land have been extractive.