- Susan Bostwick

- Rob Connoley

- Katie Englemeyer

- Gayle Fritz

- Bill Iseminger

- Jennifer McBride

- Natalie Mueller

- Lynn Peemoeller

Lost Crops Conversation

In early September, the partners of Field Station 3’s Postnatural Landscapes project met at Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site in Illinois to view the demonstration garden, this year curated by paleoethnobotanist and ancient crops expert Gayle Fritz and food systems planner Lynn Peemoeller. The group discussed the evolution of agriculture and foodways in the region and how that has affected representations of landscape, cuisine, and a cracker box. What follows is an edited version of this wide-ranging conversation.

Conversation participants:

Susan Bostwick, Artist and Educator; Katie Englemeyer, Summer Site Worker at Cahokia; Jennifer McBride, undergraduate SIUE in Archeology & Native American Studies; Natalie Mueller PhD, Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Washington University; Gayle Fritz PhD, Professor Emerita of Anthropology, Washington University; Rob Connoley, Executive Chef Bulrush; Bill Iseminger, Assistant Site Manager, Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site; Lynn Peemoeller, Food Systems Planner (Project Lead & moderator)

Lynn Peemoeller: What brings us together is the fact that each of us has hands-on experience of working and interpreting the materiality of the earth. You’ve each developed your own way of looking at local landscapes here along the Mississippi River. To me, what’s evocative about this project is that it allows me to revisit my training in geology and think about time in a material way, that’s represented in landscape stratification, of the earth, the flood plains, the seasons, and less obvious artifacts that we find flowing below the surface. When we’re learning how to read a landscape, we can learn an awareness of time in its raw form.

This project gives us an opportunity to tell a narrative and give it a contemporary relevance. I would like to talk about that timefulness aspect of it. Natalie and Gayle, perhaps you could start by talking about the awareness of time in your work, and more specifically about the time periods you study and how you develop an understanding of human activities within those timeframes.

Gourds grown in the garden at Cahokia. Photograph by Lynn Peemoeller

Gayle Fritz: The early part of the domestication, cultivation and agricultural trajectory goes back to squashes and gourds, 5,000 or more years ago. The wild gourds were being observed and harvested, and then seeds cultivated and passed around way to the north of where their natural range was. This was already within a framework of change—of landscape management in terms of burning forests and opening up parts of the landscape that had been closed for higher productivity of nuts and native fruits.

The squashes and gourds come in, in what appears to be an insignificant way at first, through being found along the rivers and then used for a number of purposes—the flowers and the seeds for food but also the hard shells for containers and as musical instruments. Then, several thousand years later, we still had hunters and gatherers. They were largely non-sedentary, although they would come back to the same base camps year after year, within this managed forest landscape. That’s how some of the native seeds arrived.

Natalie Mueller: Picking up that thread around 4,000 years ago, it’s from then that we have the earliest evidence for seed crops being domesticated, which are similar to what we would call grain today. Whenever we see the first evidence for domestication, the archeological record is almost certainly hundreds to thousands of years after people starting cultivating things, because domestication represents a not an end point, but a recognizable point in an evolutionary process that has to have started before you can recognize it, if that makes sense. Around 4,000 years ago then, we start to see evidence relating to a couple of the grain crops that I study, which are called sumpweed and goosefoot.

Sumpweed (Iva annua) and goosefoot (Chenopodium berlandieri) were both domesticated around the same time, about 4,000 years ago. When we say that, we mean we can actually see a measurable difference in some aspect of the seeds that we find in the archeological record. In the case of sumpweed, that’s an increase in seed size, which is common change that occurs in domesticated annual seed crops across the world. In goosefoot, it’s a little more complicated. The changes that occur are partly an increase in seed size, which is actually an increase in seed volume, so it’s a change in shape, but still means more food for people to eat and stronger, more vigorous growth for seedlings because they have more to draw from.

There’s also a decrease in the hard-protective coat around the seed, which is what prevents it from germinating. After five years of growing these things myself, I think that’s actually the most important and least well understood aspect of the domestication of annual plants, because when you’re going through the process of transitioning from managing a wild stand to actually opening up a field and planting things, the most important thing to understand is how to get the seeds to germinate. If they don’t germinate then you’ve just wasted all your time—that’s happened to me many times.

Lynn: What seeds are you germinating? Are you using actual ancient seeds?

Natalie: To be clear, I’m not growing ancient seeds. I’m growing the seeds of modern plants that we call the wild progenitors of the lost crops, which means the wild ancestors, but they’re not actually the ancestors of the lost crops, because they exist further ahead in time. So what they are is either relatives of the wild ancestors of these crops, or, a more interesting possibility that we would need to investigate through DNA, is that some of these populations are actually feral, meaning that they’re the descendants of the domesticated crops.

We could be wrong in our experimentation in the sense that potentially we’re using descended populations as representative of ancestor populations. They could already have some changes—a genetic legacy—associated with domestication before they went feral and were no longer tended by people. We just don’t know yet. We have to look into the DNA to get at that.

Lynn: It’s interesting that the tracking of time and DNA are not necessarily parallel. They’re intertwined and perhaps forking paths.

Natalie: We talk about wild progenitors of crops all the time as if they still existed, but the real wild progenitors of crops are the seeds that we would find in sites from 6,000 years ago, not the plants that are growing in the landscape today. They could be really different. Even if they aren’t feral, they’ve still been evolving for the past 5,000 years. They’re not going to be exactly the same as they were 5,000 years ago, especially because they’re annual plants.

Gayle: Examples include the wild ancestor of the Cucurbita pepo, subspecies pepo, the Mexican pumpkins and squashes that were independently domesticated at around the same time or even earlier than the pepo ovifera, the eastern squashes that we’re growing here, represented by the acorn, summer or yellow squash. We think we know the wild ancestor for the eastern one, a Cucurbita texana like wild gourd that still grows. There is no known wild ancestor for the Mexican pepo pumpkin—it’s been domesticated out of existence.

Lynn: Let me bring up an interesting concept that cross references the Anthropocene with the work that we’re doing and talking about, contextualizing selective breeding. The idea of postnatural histories is something that has emerged in literature looking at that role of human interaction, when referring to living things that have been intentionally (consciously or not) altered by human beings through domestication, selective breeding, induced mutation, and genetic engineering. That’s referring not only to plant species but also animal species. Of course, Darwin is a big part of this framework for thinking about that role of co-evolution. One idea the Anthropocene represents is the end of division between people and nature.

What we’re talking about now is the history of civilization as a history of seeds. I’m curious that, from a scientific point of view we’re using seeds as a way to practice a cycle of life, but also as a representation for marking time and culture. One image I’ve always found particularly striking is about morphological evolution, specifically of corn, Zea mays. As in, how over time it transformed from teosinte, a stringy grass, to the swollen ears of corn that we see today. Gayle, you’ve talked about the “Zeafication” of history. How do we understand those changes through the landscape? How do we reconcile what we recognize today as food with the history and postnatural co-evolution of those crops?

Gayle: I still haven’t wrapped my head around the postnatural; it’s still evolving. My immediate reaction was that it’s not really a term that is going to be embraced by archeologists.

Lynn: Why not?

Gayle: Taking it back into the past, all of these things were happening, that were changing the landscape, changing people—co-evolution and domestication were happening. I see that. I’m ingrained in seeing that as part of natural evolution. I don’t want to separate people from nature.

Susan Bostwick: That’s exactly what I was thinking, that we are part of the natural world.

Natalie: I think what we’re saying is that’s perhaps not a new insight for archeology . It’s not like now that we’re in the Anthropocene, there’s no separation between people and nature. Because of the way we do our research, we’ve always seen people as being embedded in ecosystems and that’s been part of what we study.

I’ve been reading a lot of multi species studies recently because it obviously intersects with what I do. I really like a lot of it but one thing I find very frustrating is that the sense that many people in humanities disciplines are just realizing what people in ecology have been doing for the past 100 years. This attentiveness to other species, it’s not a new thing within science—but it’s also not a new thing within humanity. Something that’s necessary to domesticate an animal or a plant is an extreme attentiveness to its life cycle and morphology; its potential and how it grows and thrives in different contexts.

Lynn: That’s a great answer. We find ourselves in a place where we’re learning how to represent knowledge, that foundational body of knowledge that grows through research over time and which is all dependent on what comes before it as well. That intersection with humanities perhaps involves looking at some of these same things but from the different angles. This prompts me to bring this out of my bag of tricks.

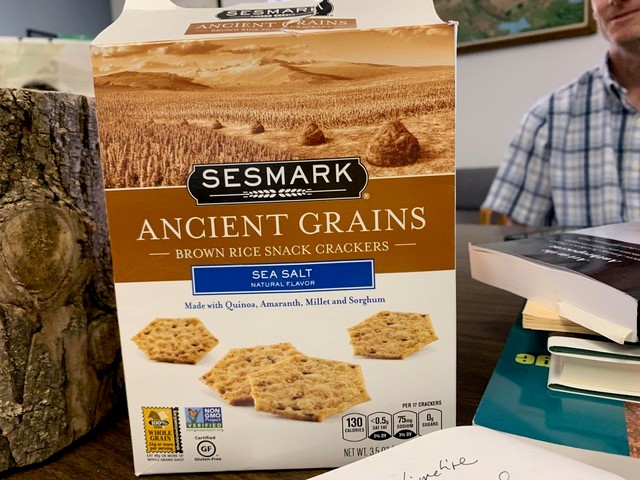

Lynn brings out box of Ancient Grains “Brown Rice Snack Crackers,” made with Quinoa, Amaranth, Millet and Sorghum

Ancient Grains “Brown Rice Snack Crackers,” made with Quinoa, Amaranth, Millet and Sorghum. Photograph by Lynn Peemoeller

Natalie: “Ancient grains” is my absolutely favorite… As if there’s “non” ancient grains.

Lynn: I will pass it around, I’d like to get some reactions. The other thing I would like you to consider is this visual representation on the packaging itself. What is the picture of? Does it represent what’s in the box? What is this artifact that we’re looking at?

Natalie: One single agricultural landscape could never represent those four grains since they come from different places in the world and are grown in totally different ways. I actually don’t know what this is supposed to be.

Lynn: I think it’s the Fertile Crescent.

Rob Connoley: We’re dissecting a cracker box.

Susan: I was thinking that it’s Monet’s haystacks.

Natalie: I appreciate those reactions because I can be really annoying in museums about the way that agriculture is presented. 90% of people are probably just think “oh, it’s a field.” Most representations of indigenous agriculture, such as in eastern North America, show the three sisters: maize, beans, and squash, though that’s starting to improve. Since lost crops are not really familiar to many people, the designers and artist that create exhibitions and displays really need to make an effort to understand what these plants even looked like in order to make some representation of what they could look like in a field setting. Even then, we don’t really know what they would’ve looked like in a field setting.

Lynn: Yet we’re in a room and we’re surrounded by images that are recreations. This is already one of the intersections.

Lynn points to painted representation of city of Cahokia

Bill Iseminger: I did that one.

Lynn: Bill, is that art or is that science? Or both in that representation?

Bill: The idea was to show that they had to have extensive fields to feed all the people here, so I just tried to make it look like a field and made it rectangular. It doesn’t have to be necessarily but that was the art part of it. It does reflect something we know about science.

Gayle: Certainly the big expanses of field in the upper right and the upper left are exactly where the fields are likely to have been. Others would have been other places too, and on the painting there are some down on the lower part. There is really good soil around the alluvial fan coming down off of the bluffs. The fields could well have been rectilinear like that. They might have been a little more elongated or have had been gaps where there were swells, and there might have been different shapes, hexagonal or polygonal forms. But I wouldn’t say that they couldn’t have looked like that. We don’t know exactly what they looked like but that’s a really good start. They’re big and they’re open.

Bill Iseminger's painted representation of the city of Cahokia. Photograph by Lynn Peemoeller

Lynn: We’re talking about time—just by recognizing the role that the visual representation does play in creating the way that we relate to something today. From different time periods, we have different styles of visual representation. Today, thus cracker box represents a particular kind of marketing. This is the ultimate capitalist representation of a packaged and ready to purchase landscape for our supposedly collective history.

Natalie: It’s an ominous image really. There’s no people for one thing. It’s a huge open expanse, probably bigger than even grain fields would’ve been in ancient Near Eastern civilizations with cities. It looks like how we grow grain now, not how people would’ve grown it when they had to do it by hand. In rural areas where people still grow things by hand you see a lot of people walking around and doing things. You don’t see giant fields full of grain that are completely devoid of people.

This visual aspect is part of the reason why we’re creating the gardens we’re working on. For the most part, it’s because I wanted to understand how people grew these crops and get inside how their agricultural system worked. But in addition to this, when you point out these plants in the wider landscape as ancient crops, many people just see them as… weeds. That’s because they’re growing a ditch or whatever, looking all sad and bedraggled. Half the time a plant has been sprayed with herbicide and is half dead. If you grow them in a garden, first of all, they look completely different because they’re happy, protected, and cared for, but it also helps people to imagine them as crops much more easily to see them in this tended landscape. Part of the teaching purpose of having them in gardens is to show this wasn’t just people gathering seeds from weeds and then they got corn and they had agriculture. It was an actual agricultural system. You have to see things being grown as crops before you can imagine them as crops.

Lynn: It’s a practice, also. We practice growing and that’s what Janisse Ray talks about when she describes more contemporary seed saving, and the passing down of these landraces and heirloom cultivars. It’s that we practice planting the seed. We practice that genetic evolution that people have been doing for thousands of years before us.

Gayle: We fail and then we practice again.

Natalie: And if we stop practicing it then the crops become lost. It’s not something that only happened here. It’s happening all over the world right now.

Lynn: What do you think is lost or gained through this process of selective breeding? How do we reckon the loss of biodiversity over time? It’s a huge question, but how does that play into your work?

Natalie: The loss in biodiversity in our agricultural system can be seen according to different time scales. I personally see the high point of agriculture in this region as taking place about 2,000 years ago. People might argue with that. What we see at archeological sites is a flawed and biased snapshot of what was going on in human created and maintained ecosystems. During that time period we can see five or six different grain crops, along with a few different annual fruit crops, trees, and bushes being maintained. That’s not to mention all of the different kinds of animals that people were maintaining or encouraging in various ways. Within our little world of people who talk about these subjects, it’s often remarked upon that Native Americans in eastern North America didn’t have irrigation and levies, almost a though it’s something they lacked.

But another way of looking at it is that they were protecting the flood plains because they produced a lot of food for without them having to do anything; it was just free food. Now we see what’s happened to the flood plains since we’ve built a bunch of levies and irrigation—they’re completely destroyed, and it takes a ton of energy to produce food in those same spaces that were previously naturally abundant. In my opinion it’s probably something the Native Americans knew was an option and chose not to do.

Working in the garden at Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site. Photograph by Lynn Peemoeller

Lynn: I want to bring in another topic and talk about foraging. Foraging is one method, both ancient and contemporary, through which we can relate to the reading of a landscape for its nutritional value. Rob, you talk about the ethics of foraging in your work. It seems like you’re laying the groundwork for a “virtuous relationship” between human and plant. To me, that seems possible on a very intimate scale. But we’re talking about contemporary within this framework of the Anthropocene. What are the limitations of scale? Do you think that it’s possible to engage with a landscape and not to have an implicit motive to exploit it? That’s a big generalization, but how might you translate that in your work?

Rob: I’m an extremist when it comes to foraging ethics. I’m still lingering on the crackers box because to me, it’s a response to a harming of our food systems. People can’t eat gluten because we’ve done what we have to wheat crops. So now we have “ancient grain” crackers and rice crackers and all these other dietary responses. In foraging, it’s the same thing. All the sudden, foraging is exciting and sexy. That started in the United States about 15 years ag while in Europe, it’s never really stopped—although it’s dwindled as well. When I say I’m an extremist in the ethics, it’s because I see people jumping on board foraging as a response to what we’ve done to our food systems, and they don’t care about the impact on the environment.

In New Mexico, particularly places where things were scarce, when I would go out, one of the main considerations I had was: What impact will my taking this plant have on the wildlife in the area? And what will the impact of this have on the environment? Meaning, if I plunder the whole cattail stand, will it come back next year? In that way, I was cultivating the crops of the forage. Here in the American Bottom, everything is so much more prolific but I’m still trying to figure out where that line is. All these things go through my head when foraging, knowing that these weeds in the garden are actually the best food. Again, that ties back to how we’ve harmed the food system. For me, this conversation is about opportunity. I don’t want to say connecting people back to the land, that’s a little too hippy for me, but it’s something similar—getting people to realize there’s food around them and the processes and systems having a detrimental impact on us can be avoided if we’re reconnected with the environment that we’re in. We just need a little bit of education to do it properly.

Katie Englemeyer: Such as accurate education about ancient grains on that box.

Lynn: We have this opportunity to create a narrative, us here together. What do we choose to represent? This idea of time and representation is really tricky. Just trying to understand the seeds, the way that you’ve chosen to cultivate your garden, Natalie, the way that we chose to do this Cahokia garden. It’s not 100% accurate, just like this box. There are different levels of accuracy but what message do we choose to portray in this work? That’s something that’s interesting about your restaurant concept, Rob, that you have put a specific timeframe on it. Can you talk about how you chose that time frame?

Rob: The timeframe is 1820 to 1870. My spouse does regional ministry with United Church of Christ and visits churches all over Missouri, Memphis and a few peripheral places. When I was first starting out, I said “When they were done with these churches in the Ozarks, could you ask about the old church cookbook. I would love to get my hands on those.” Over a half year, I received 20 different cookbooks, from the 1930s through modern times. As I looked through even the oldest of them, I found the same stuff over and over again—casseroles and jello salads. I said I’m not opening a casserole and jello salad restaurant. But, I guess that’s what I did. We just call it using fancier terms and people pay more money for it.

Those books led me to University of Arkansas Fayetteville because they have an Ozark collection, specifically a cookbook collection. I found books that took the form of old pamphlets, which I would then buy eBay because for two bucks. I have now a huge collection of those, from1915 through 1940, and also more contemporary. Those were interesting but every time I saw a squirrel casserole or possum pie, I had the feeling think it wasn’t authentic. Over time I realized that those were written for tourists. I connected that though to Shepherd of the Hills, by Harold Bell, the quintessential book that brought people to the Ozarks. Anything after the date stamp of that book, is not as interesting to me because it’s aimed at the tourist. The archivist at Fayetteville pointed me instead to Little Rock. I went looking for books, but they would bring out family scrapbooks and letters. The restaurant period’s start date of 1820 comes from the date of the oldest letter I laid my hands on. The end point of 1870 is because anything after that started to look too much like what I would see in Appalachia or down in New Orleans or up in Minnesota. Mass communication had kicked into a level that that information was no longer isolated to the region.

The amount of information I found started to get unwieldy but now I have an intern from St. Louis University transcribing all these documents and we’re going to go back to Little Rock to start re-researching and seeing what else we can find. So, our timeline will shift. We know it will.

Lynn: Are you looking for recipes specifically?

Rob: You don’t see recipes until after the introduction of baking powder around 1843. There were some recipes but not very many. I can’t think of anything else that I would find pre-baking powder other than pone, which, again—why do you need a recipe for pone? It’s cornmeal and water and there you go, fry it up. So that’s why the restaurant’s time period exists, and it will change because the Ozark was where I plateau started. But what really defines Ozark cuisine to us is these stories and traditions that we have accurate documentation of , which we can bring back to contemporary times and give a new life. That’s much more exciting to me versus trying to say exactly determine “is this Ozark or Appalachian.” What’s the difference?

Natalie: It sounds like you’re talking about ancient times too. Our best evidence for what was going on with the lost crops throughout the entire era that they were grown comes either from the Ozarks or the Appalachian Mountains—and that’s because those are the places where they’re well preserved in caves and shelters. Even though the agricultural system was basically the same in both places, it wasn’t exactly the same. There were some plants that were only grown in the Ozarks, including mystery ones that still haven’t been identified.

Vessel Interpretation in progress. Photograph by Lynn Peemoeller

Lynn: I wanted to bring Susan into the conversation before we end, because I think your work is very interesting in the way it works materially with clay. We all know that this region is famous for its clay deposits. What’s fascinated me about Saint Louis is that it was built on the clay industry and the extraction of that clay was hugely important during the 19th century.

Susan: Bricks.

Lynn: The brick industry, which is pretty much shut down at this point. What I see as common for both you and Rob is a foraging relationship with the earth that’s both ancient and a contemporary. It one you’re still developing, as someone who searches for clay seams and deposits that can be utilized for pottery specifically. In other words, you’re practicing what we recognize as material extraction but through ancient methods. You’re also a gardener. What do you think the relationship is between the past and the present in your work?

Susan: I’m a gardener who teachers and has also made a lot of pots. What I teach folks about ancient technologies is that we can pretty much go anywhere on the planet and dig clay. In this project, we find that we’re going to creek beds because there mother nature has done the work and we can find seams of clay. Clay is ancient and it’s everywhere. We’re trying to tie a specific clay with specific pottery. That being said, as a contemporary potter, there are clays that we have mined out of existence on the but planet that are reproduced in factories. It’s not just the potters who are responsible of course, but industry. Again, just materials that are no longer available to us. You would think again, clay is so plentiful, but these ones aren’t available in the earth.

Lynn: When we met here at Cahokia Mounds State Historic Sites several months ago, we walked around and looked at all of the artifacts and discussed their youthfulness. I know that you’re interested in the Woodland and Mississippian period, spanning 250 to 980 BC. Do you find that you represent those forms in your work, or are you translating them? And are you interested in the same functionality as they held?

Susan: As a potter I’ve always really tried to make pots that contribute to a sustainable earth. But people would end up buying pots and displaying them and not using them. That’s a challenge as a maker because if people are going to use them, then I have to make them affordable. There was one potter who just died recently, Warren McKenzie, who brought that whole philosophy to the U.S. from Britain. In my own work, I’m more inspired by ceremonial artifacts, the effigy pots. I’ve often incorporated animal imagery into my work. I try to blend something functional with something more ceremonial. I make funerary urns, for example.

What really inspires me with the ancient pots is technically how they’re made. I look at these pots and think about how the walls are this thin and we know nothing about the technique! I’m trying to learn more about the temper that people used, which was mussel shells primarily. When we’ve gone out harvesting, I’ve then realized that I need to know about the mussels because there’s invasive mussels and there’s native mussels… If you’re on private land, it’s your own land and it’s okay. But on public land, you need a fishing license and you’re limited to so many mussels per… so now I’m a geek—every time I go to a restaurant and anybody is eating mussels, I’m like can I keep those shells? I know it’s not accurate because they’re not from around here, but it’s sometimes the only way to get plentiful mussel shells that I can process and then wedge into the clay. So, I think my lines are blurring a little bit more. I’m trying to better understand ancient pots, how they’re made, how they were used, with my contemporary concerns.

Lynn: There’s so much there in terms of parallel. We’re in a contemporary space here today, looking at the functionality of these landscapes and interpreting them from the past to the present. We all bring our own work to those interpretations. There is so much overlap and potential to share knowledge when it comes to clay, the role of cuisine, culture, ethnobotany. From our cross-collaborations we are building a knowledge base and living archive of how people and plants co-evolved. It’s been great to get to a glimpse of what people were cultivating in ancient times and how we might interpret and utilize those remnants and practices today.