Maa Wákąčąk: Sacred Earth in the Anthropocene

During the 20th century, the ground known to the Ho-Chunk Nation as Maa Wákąčąk, one of the tribe’s most sacred sites, became home to one of the US military’s largest ammunition producing facilities in the world. Today, the site is broadly presented and perceived as a site of conservation. Yet, as Sarah Kanouse for Temporary continent. recounts here following a trip to Maa Wákąčąk in the frame of Field Station 2, these histories of conservation and conquest are anything but “past,” and continue to overlap and exert anthropocenic influence on this sacred earth.

Vehicles turn into the cracked, concrete parking lot under a grey drizzle. First a few, then a few more. We are nearly all late due to some combination of distance, weather, and the need for breakfast. The damp chill prompts many people to wait in their cars, breath fogging glass. Our host, Randy Poelma, environmental specialist for the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin, stands outside his truck in a green rain jacket, chatting casually with the handful of people who venture out of their vehicles to explore the surroundings.

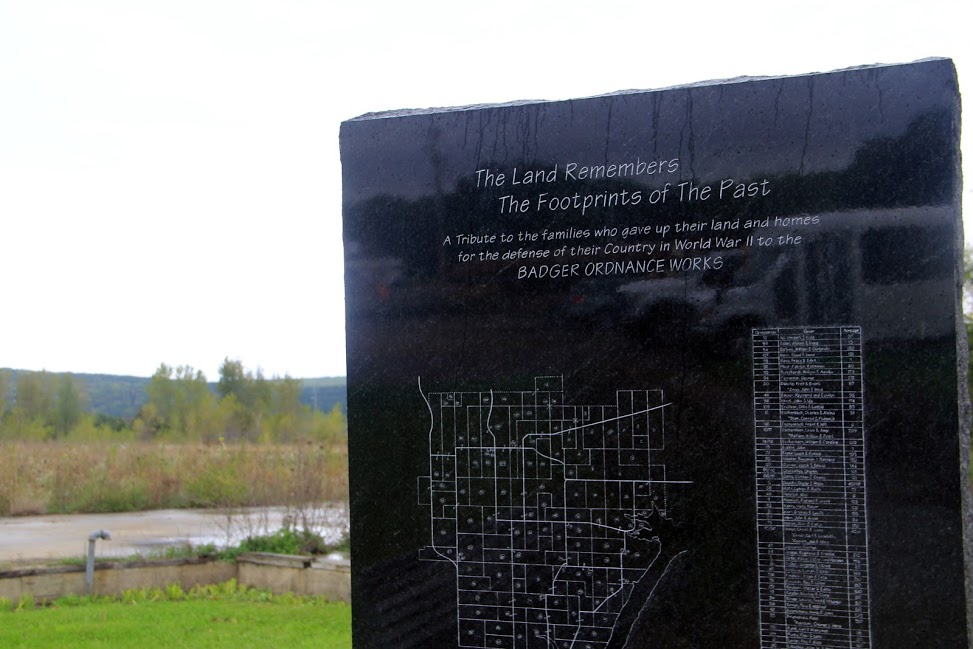

We are assembling near the gate of what was once the largest ammunition plant in the world. Operating during the Second World War, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, the 7,500-acre Badger Army Ammunition Plant was best known for making rocket fuel and “smokeless” powder: a projectile propellant whose chief military asset was its ability to fire upon opposing troops without a plume of smoke to give away the position of the attacker. Placed on standby status in 1977, the facility was declared surplus property and closed in the late 1990s. The military history of the site is celebrated in the volunteer-run museum housed in the only surviving building visible from the road. A black, granite monument to the farmers whose land was seized to build the plant occupies a patch of well-manicured lawn, incongruously lush amid the pavement and brittle autumn grasses that grow in its cracks. Neither museum nor monument has much to say about Maa Wákąčąk, or “Sacred Earth,” the Ho-Chunk name for the tribe’s land restoration project on the former ordnance works and the reason for our visit this rainy Friday.

Photo by Ryan Griffis

Military activities produce quintessentially Anthropocenic landscapes that are both “unspoiled” by urban development and profoundly “disturbed” by the environmental and moral legacies of such enterprise. Many former military sites combine high levels of biodiversity with dangerous levels of contamination ranging, from the industrial mundane (lead, asbestos, PCBs) to the very specific toxic residues of war. Despite twenty years of remediation, the groundwater at Badger is contaminated by a plume of dinitrotoluene, or DNT, and recent tests have detected per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), whose effects on ecosystem and human health are not yet well understood. The twentieth century’s cavalier attitudes toward environmental safety and lax record-keeping mean that the extent of improper disposal and chemical dumping at former military sites may never be known. Because conservation lands are less intensively used by human beings than, say, residential, agricultural, or commercial facilities, the Environmental Protection Agency permits a lower level of remediation to take place—often relying on so-called monitored natural attenuation, or essentially doing nothing but allowing time to pass with periodic water and soil testing. Geographer David Havlick has dubbed this “opportunistic conservation,” or a way for the army to limit their responsibility for the chemical plumes that persist decades after the last “smokeless” powder ignited.

Maa Wákąčąk is both more complicated and more interesting than most other conservation projects on former military lands. As Randy explains after leading us into a non-public area of the former ordnance plant, the army isn’t the only entity to find opportunity in returning this contaminated land to prairie. Using a law granting tribal governments the right to surplus federal land, the Ho-Chunk mounted a decades-long campaign to acquire Badger, ultimately persuading a reluctant Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) to place 1,500 of the least contaminated acreage in trust for the tribe—a transfer finally completed in 2014 as part of the National Defense Authorization Act. The land is adjacent to Te Wákąčąk, known to settler society as Devil’s Lake. The name gestures, through inversion, to the lake’s sacred status to the Ho-Chunk, who know it in English as “Spirit Lake.” Randy, a non-Native career employee of the tribe, explains why tribal elders placed the highest cultural and spiritual importance on restoring a land base adjacent to Te Wákąčąk.

Although the physical restoration of the land is in its infancy, Randy helps us see beyond the crumbling grid of asphalt, the incongruous stands of feed corn, and the late-season meadow grasses that recede in the mist. He speaks of 406 tons of creosote-soaked railroad ties removed, tons of contaminated dirt excavated, scores of invasive shrubs ground into wood chips, and even the strategic use of short-term leases that let the tribe outsource the eradication of the soil’s bank of weed seed to tenant farmers growing RoundUp Ready corn. We learn that the restoration is funded by leasing 170 acres to Sierra Nevada Corp., a Nevada-based rocket company developing engines that will service the International Space Station starting in 2021. The lease was re-negotiated after SNC acquired a legacy tenant, providing an opportunity for the tribe to demand safe removal of asbestos-ridden buildings, the use of non-toxic propellant, and the creation of a STEM training program for Native youth. Randy and his colleagues carefully source prairie seed from within a 100-mile radius to preserve local genetic integrity while selecting a plant mix that will withstand rapidly changing climate conditions. The tribe maintains a federally certified, 10-person fire team that performs prescribed prairie burns on their lands and travels to the west to fight forest fires on government land. Elders look forward to gathering milkweed and other sacred foods and medicines each summer. Once the prairie is established, the tribe plans to reintroduce bison. As Randy speaks, we come to see that Ho-Chunk conservation practices are not separate from cultural values and economic needs. Rather, the restoration of this land is a multivalent process that supports subsistence in both monetary and spiritual economies. Maa Wákąčąk emerges not as a sentimental restoration of a stable prior ecology but rather a post-Anthropocenic realization of traditional ecological knowledge through sophisticated legal strategies, business acumen, and conservation best practices.

Toward the end of our time together, Randy takes us to the most Instagrammable portion of Maa Wákąčąk, a collection of original buildings and a concrete bunker that haven’t been yet been dismantled. They have all the romance of ruin porn: broken glass, moss encrustation, obscene graffiti, trees breaking through walls. I take some photos, but I’m too embarrassed to upload them, and besides, there’s no cell service so far off the main road. Randy shows us that the holes drilled by the army to test munitions inside the billion-year-old Baraboo hills have been converted to habitat for hibernating bats. While the tribe ultimately wants to get rid of the hulking concrete blast wall, the remnants of the army’s occupation have been repurposed to shelter a species decimated by the worst wildlife disease of all time: white nose syndrome, which has killed millions of bats across North America.

One of the dangers of military-to-wildlife conversions is that they can appear to retroactively justify the military use of the land and, by extension, the larger project of war making and conquest of which it was a part. This narrative is sometimes invoked at Badger: the army’s wartime acquisition of white-owned farms is what allowed the Ho-Chunk to ultimately regain Maa Wákąčąk. This framing seems to demand gratitude for the army’s occupation of the land, conveniently forgetting that it was the army that forcibly removed the Ho-Chunk in the 19th century and that it was the army that so contaminated Badger that the BIA could only be persuaded, after a nearly 30 year campaign, to transfer a small portion of the property to tribal trust. Without making an explicitly political point, Randy’s description made clear that the leftover army infrastructure didn’t just provide bat habitat so much as require modification in order to be habitable by bats. These details matter, as the question of whether the Anthropocene is to be survivable, and for whom, requires rhetorical practices, material acts, and transformative narratives as those underway at Maa Wákąčąk.