Navigating the Anthropocene River

A traveler’s guide to the (dis)comforts of being at home-in-the-world

In September 2019, a group of travelers boarded a set of canoes and set off from the Mississippi River’s headwaters in Lake Itasca, embarking on a hundred-day journey down the river’s length: the Anthropocene River Journey, in which twenty-five scholars, artists, and activists along with students from River Semester of Augsburg University in Minneapolis, Minnesota participated. In this essay, Joe Underhill, who organizes the River Semester at Augsburg University, recounts the many experiences the travelers underwent on both land and water, relating them to the ideas and practices of what might constitute an “Anthropocene curriculum.” Confrontations with the often destructive social, economic, and political realities of those who live along the river offered a stark contrast with the more joyful, even spiritual experiences of life in the field. Critically reflecting upon this experiment in immersive, field-based education, Underhill and fellow travelers offer an exploration of the (dis)comforts of an approach that they suggest could be called “being at home-in-the-world.”

“The wreck of the Anthropocene future.” A toy Landspeeder washed up on a beach on the Lower Mississippi. Field Note by Joe Underhill

This essay explores the idea of an Anthropocene curriculum that connects students directly to the world through immersive, field-based education while practicing a form of low-carbon, sustainable living. These life-affirming and meaningful experiences are much needed in the midst of the generally grim realities of the present era, made all the more daunting now by COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, this is an exploration of the (dis)comforts of what could be called being at home-in-the-world. This is both a radical rethinking of the praxis of higher education and a pedagogical form that allows for a nuanced, balanced, and complex understanding of the Anthropocene. This notion is explored via the example of the River Semester, a hundred-day canoe journey down the Mississippi River in 2015 and 2018 (with the next trip planned for 2021). A custom form of this expedition, organized in partnership with the Haus der Kulturen der Welt and Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, took place in Fall 2019 under the title of the “Anthropocene River Journey.” These programs were conceived as lived experiments and performative acts of rebellion against existing practices in higher education and as correctives for the resource-intensive norms of modern Western consumer capitalism. An Anthropocene curriculum needs to provide opportunities for the life-affirming communal experiences and connections with what remains “natural” in the Anthropocene. We have found these experiences to provide students with the skills and mindset needed for the long journey ahead and to be powerful medicine for the anxieties, anomie, and dysfunctions of our day.

Introduction

In these precarious times—variously referred to as the Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene, climate change, the Great Acceleration—those attuned to the realities of the global dynamics and trends, and called to respond to them, face a daunting set of challenges, stresses, and psychological strains. Maintaining hope, a sense of purpose, health, and sanity in the midst of the Sixth Extinction, rising sea levels, catastrophic floods and fires, resurgent xenophobic populist nationalism, and global pandemics is no small feat. Teaching and learning in this context require a curriculum that engages with these difficult and complex realities and also an intentionality around the ways to inspire hope and the sense of agency needed for the work that will inevitably be required to navigate the (literal and metaphorical) storms that lie ahead.

As Alya Ansari, one of the participants in planning workshops for the Anthropocene River project, puts it:

The Anthropocene has raised more questions and uncertainty about the ways in which we live and know than it has delineated a clear, forward course of action. What does it mean, concretely, to do the kind of comprehensive reformation of knowledge production that the Anthropocene calls for and enables? How do we resist within the Anthropocene, and how do we use the agency the concept bestows upon us to grapple with the harsh realities of a world we have created?

These canoe-based, semester-long expeditions down the Mississippi River, by their very nature, entail a thorough exposure to and immersion in the social, political, and anthropocenic realities of life in the American heartland. Stripped of the protections and comforts of life indoors and away from the screen-dominated (ir)realities of the digital age, the travelers on these journeys come face to face with the industry, poverty, wealth, wilderness, pollution, beauty, injustices, vitality, and dysfunction of natural and human communities all along the river.1 The students on these trips face the rigors of paddling hundreds of miles on a major river in all kinds of weather and attend to the duties and needs of the expedition, all while taking a full load of college credits. In a significant expansion of the usual programming, the 2019 Anthropocene River project, involved close to 500 scholars, activists, artists, and community organizers in a complex, multifaceted investigation of the Mississippi River as part of the hyperobject of the Anthropocene.2 The Anthropocene River project has produced (and continues to produce) a rich body of research, in various forms. As one early attempt to collate and reflect on at least some portion of this multimedia “raw data,” this essay draws on the resulting mix of field notes, art and research projects, and short contributions, as well as the experiences of the 2019 and earlier River Journeys. Photo documentation and field notes are inserted as illustrations of points raised in the text, and also as standalone vignettes that capture moments and sites that stood out for the river travelers.

One of the most notable elements of these journeys is that they are much more than the standard educational endeavors of research and knowledge acquisition. At many points along the way, participants have broken down and wept. This journey through the Anthropocene is emotionally laden and requires us to move from the cerebral and more narrowly academic concerns to our hearts and bodies and to notions of self-care, health, joy, and thriving. A central question raised by the experience of an extended, mostly human-powered voyage through an anthropocenic space is what the sustainability of those efforts is, in personal and emotional terms. In other words, how can we live and find joy in the midst of such immersion in the challenges and stresses of the Anthropocene?

These heroin syringes, found scattered near urban camps in Minneapolis, are but one vivid indicator of the pain and desperation of our times. Field Note by Joe Underhill

The historical and intergenerational trauma and solastalgia (sense of environmental loss) caused by the displacements and genocides of settler colonialism, slavery, racism, lynchings, war after war after war, pollution, the loss of beauty, the clusters of cancer in communities of color, constitute a challenge to the human spirit and contribute to the increase in stresses and mental illness nationally. As one recent report outlines:

From 2016 to 2017, the number of adults who described themselves as more anxious than the previous year rose 36 percent. In 2017, more than 17 million American adults had a new diagnosis of a major depressive disorder, as well as three million adolescents ages 12 to 17. Forty million adults now suffer from an anxiety disorder—nearly 20 percent of the adult population. … [Among] all Americans, the suicide rate increased by 33 percent between 1999 and 2017.3

Much will be asked of us in the years ahead, and in ways it will always be more than we are capable of. We already are and will always fall short, witnessing—as we currently are—destruction, deaths, extinctions, and injustices on a daily basis. This question of how to live in the Anthropocene entails the double project of finding that balance that allows us to do what we can without becoming exhausted, while also having the time and space to respond (mourn the losses, celebrate the partial victories) that will inevitably ensue.4This amounts to finding a home in the midst of all this chaos—a place of refuge, a sense of belonging and community, a connection to place, and a space within which we can thrive and be creative. We might call such a space a home-in-the-world. It is a way of living in the Anthropocene that allows us to engage with the realities and challenges of our day, minimize our environmental impact, and maintain a sense of agency. Each person experienced the journey differently. During these various river journeys, many participants at times did feel overwhelmed, anxious, frightened, or ready to call it quits. But at many points during our river journeys, we also felt decidedly at home on the river. We experienced joy there—living simply, with far less of the material possessions that separate us from the world, slowing down, using our bodies to do the daily paddling and setting up camp, sitting around the fire, to swim in the water, to experience a sense of reverential belonging, of grace. One such moment happened as we paddled through a thick swath of wild rice, when two Ojibwe rice-harvesting canoes silently emerged, quietly pushed along by men with long poles. There was a brief greeting, then a return back into the rice marsh, the boats swallowed up and disappearing into the tall grass. This display of connection and harmonious relationship with the land was inspiring, and reflected a certain hunger for that kind of connection among our group of river travelers.

A central element to the notion of home-in-the-world is the spiritual and ritual or ceremonial aspects of that space. Under the vastness of the sky and immersed in the unknowable mysteries and deeply troubling realities of the world, the river travelers instinctively moved toward—hungered for—the comfort afforded by ritual and ceremony. This longing for a sense of connection and meaning affirmed the importance of the journey as a pilgrimage, not toward the otherworldly redemption of a Christian heaven but toward deeper connections to the world, to each other, and to the sublime. In all this, the mysterium mysteriorum was the gigantic, majestic, magical entity of the Mississippi River itself. Each time we returned to the river, it was, as in the words of the traditional spiritual, like we were “going down in the river to pray.” Each time we swam in its waters, we were being baptized. The river at various times healed us, frightened us, washed away our sweat and our sins, and steadily carried us along toward the sea. In the midst of the relentless reminders of the damage wrought by the capital-industrial-military complex, the palpable constant of the river’s flow was calming. Despite all efforts to control it, to use it as a sewer and a dumping ground or a highway, the river has not been stopped or killed. It remains a force greater than us that came before and will be here after. We took some comfort in that fact.

Emily Knudson swimming at the mouth of the Mississippi River at Lake Itasca. Immediately, the impetus was to “get in the water” and connect with the river in an embodied way. Field Note by Joe Underhill

In the modern era, home is generally thought of as a sheltered, cloistered space, separate from the vicissitudes of “the wilds.” Temperature and humidity are controlled to stay within certain narrow bounds of comfort. Other people and creatures are carefully excluded, their movement controlled by walls, doors, screens, glass, and locks. This sense of home is tied to place as private property. Being at home-in-the-world, on the other hand, requires leaving the confines and controlled environments of the technological home and setting out into unfamiliar and largely uncontrolled terrain. It entails risk, exposure to the elements, improvisation, and flexibility—what anthropologist Anna Tsing refers to as “engagement with precarity.”5On the river, we travel a meandering path, which requires the exercise of what the ancient Greeks referred to as mêtis, or the improvisational skills needed to problem solve in the field. That is, we have to adapt to conditions, ask around, move camp, find shelter, live with some bugs, put on sunscreen, don a raincoat. This kind of outdoor living entail some exposure to the pollution, poverty, anomie, and floods that constitute a large part of our contemporary reality, without rendering oneself too uncomfortable or in danger.

The next section of this essay recounts our attempt at finding such a home-in-the-world, using a handful of scenarios from our journeys on the river to illustrate a few aspects of the Anthropocene curriculum. Following this, it turns to a description of the kind of curriculum called for by these times, looking at the psychological dimensions of this experience and exploring the physical and energetic limits and ways to navigate the emotional terrain of the Anthropocene.

Education on the Anthropocene River

Audrey Buturian Larson and the hybrid space of the headwaters, where the river does the thinking for us, where we disappear into a tangle of reeds and begin the meandering path from these wilds to the heavily industrialized Petrochemical Corridor (between Baton Rouge and New Orleans) and on to the Gulf of Mexico. Field Note by Neli Wagner

Although the specific itinerary and programming, weather, and composition of the group differs each time we travel down the river, the journeys share a certain arc to their roughly one hundred days, spent moving from the Mississippi River headwaters in Minnesota down to the Gulf of Mexico. The odyssey constitutes a kind of “pilgrim’s progress” through the Anthropocene, with hints of a way forward—not out of the Anthropocene but into a way of finding a home within it. At points along the way, the journeys have included encounters and conversations with river elders and other local guides who have provided insights that hint at what came before, what has been lost, and what might yet be possible again. Most of the river and watershed are heavily industrialized and engineered, but scattered throughout the journeys are also signs of resilience, agency, and hope. Being out on the river can often be discouraging. But it can also provide evidence of the strength and vitality of the river, and of the natural world in general. In spending an extended period of time on the Mississippi, we are reminded of the basic truth that the world is always more complicated than it is made out to be in any given abstract representation of it.

Although the dynamics and processes of the Anthropocene seem to engulf us, the colonization of the river is not complete. There are guides and mentors along the way—Indigenous voices, women artist-activists, river angels, river rats—who offer wisdom and perspective on our journey through the mixed dystopic, pastoral, and thoroughly anthropocenic landscape. At the beginning of our journey as part of the Anthropocene Curriculum, for instance, we met with Shanai Matteson and Graci Horne, who helped to orient us to the headwaters and Indigenous history of the Upper Mississippi. Horne, a Lakota/Dakota artist-activist, shared with us four questions used in her community to introduce oneself to a group: Who am I? Where am I? Who are my people? and What are my intentions? Her challenge to us was to critically reflect on our presence and roles within this settler-colonial space. Simple as they were, these questions challenged us and stayed with us throughout the journey, helping to ground us in place and in community with each other and with the people we met along the way. She likewise spoke of the river as a “Tree of Life” in the middle of Turtle Island (the Indigenous name for the North American Continent), and our group would come to see the river and watershed as a source of life force and spiritual sustenance along the journey. Horne invited us to think about those Indigenous lives that were lost, and continue to be lost, on and along the river, and to give tobacco in offering to them as we went (which we did on a few occasions). The challenge presented to us at the start of our journey was how to acknowledge and constructively engage with this history as a group of mostly white, affluent academics.

Graci Horne, her daughter, and Shanai Matteson at the pre-trip orientation at the Wilderness Inquiry headquarters, Minneapolis. Field Note by John Kim

At the Mississippi headwaters, the landscape provided some sense of the premodern possibilities, in the land (in Dakota, Makoce) where the waters (Mni) reflect the sky (Sota), and our group formally acknowledged that we were on Indigenous land. Where we started at Lake Itasca the human alterations of the landscape are often subtle and hard to discern. At Coffee Pot Landing, where we first launched our canoes, Gaagigeyaashiik (Dawn Goodwin) offered prayers and reflections on the sacredness of the land, in the first of what would become a series of rituals and informal religious ceremonies we engaged in along the way. A month later in St. Louis, Saundi Kloeckener of the Native Women’s Care Circle taught us about the water blessing, which her circle performs every Sunday morning and which became a regular—and powerfully healing—part of our group’s experience for the remainder of our trip.

Gaagigeyaashiik (Dawn Goodwin), whose name translates as Everlasting Wind, sharing her story of her relationship to the land, its sacredness, and the power of blessings. Field Note by Anthony Tran Students studying and listening to an audio recording of Naomi Klein’s "This Changes Everything," with a view of a coal-fired power plant. Field Note by Christoph Rosol

As we left the headwaters and proceeded downstream Upper Mississippi (between the Twin Cities and St. Louis), our time on the Mississippi River repeatedly confirmed that we live in an era of grave social and ecological challenge. To help bring about the historically unprecedented economic and social transformations called for by these challenges, we will need something more than a curriculum that is embedded within the modern fossil-fuel-powered economy, rooted in medieval scholasticism, and structured by the narrow and atomistic structures and epistemologies of modernity. But the River Semester is one attempt at imaging such an alternative. The Anthropocene is bringing about the collapse of conceptual and disciplinary boundaries, connecting the local and global via the technosphere, eliding nature and culture, and entangling us in “clashing temporalities.” Our experiences on the river reflected these complexities and entanglements. We were neither in the wilderness nor in “civilization,” but in a thorough mix of the two, experiencing always a balance between the harm caused by humans, and, at the same time, the strength and vitality of the riverine ecosystems. The hybrid and liminal nature of the Anthropocene requires an increased competence in intercultural diversity and interdisciplinary thinking, as well as practical training that moves beyond the theoretical confines of the academy. The program offers action-oriented education that is localized and applied to problem-solving, resilience, and coping skills for operating in stressful, even traumatic, situations. The river journeys provide an array of opportunities to engage in this kind of learning and provides hints of what a curriculum fit for the Anthropocene might look like. These times call for ways of teaching, learning, and doing research (and living) that are commensurate with the scope of the societal transformations being wrought by the Anthropocene—that is to say, what is needed is an education for systems change, not an education for learning how to function or thrive within the existing system.

South of La Crosse, Wisconsin students and faculty getting an embodied sense of the scale and feel for the Anthropocene landscape, scrambling up a pile of sand created by the ongoing efforts of the US Army Corps of Engineers to dredge the main navigation channel of the Upper Mississippi River. Field Note by Christoph Rosol

As part of what the environmental engineer Peter Haff has termed the technosphere, the landscape we moved through has been altered in countless ways to conform to the needs of commerce, heavy industry, industrial agriculture, and urban settlement along the river. Ours was a passage through a landscape and ecosystems that have been altered on every scale—from the macrolevel, evidenced in the geomorphology of the river, to the molecular, seen in the biogeochemistry of the water, soil, and air. The most immediately obvious transformations for us were the anthropocenic landscapes, such as the dredge spoils (the artificial mounds of sediment), concrete revetments (riverbank reinforcement), energy production and industrial sites encountered along the way. These forms of human alteration stand in contrast to the unstoppable flow of the river and the ongoing battle between the transportation and industrial infrastructures (constructed primarily by the US Army Corps of Engineers) and the natural hydrology of the Mississippi. The dredge piles were the work both of the river (constantly transporting and depositing sediment along its path) and the engineer corps, endlessly scooping sediment out of the river in a Sisyphean attempt to maintain the nine-foot navigational channel of the Upper Mississippi.

A view from the deck of a concrete barge on the heavily industrialized river in St. Louis Field Note by Temporary continent.

The capitalist ruins, and ongoing industrial activities, along the river were likewise a steady presence during our journey. The greatest concentrations of these sites is in Missouri around St. Louis and in Louisiana’s Chemical Corridor between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. Sauget, Illinois (formerly known as Monsanto Town), a quintessential company town, was created by the chemical manufacturer as a refuge from local regulations and taxes. It is now largely abandoned, replete with toxic waste sites. In the grim environs around St. Louis, we traveled from this to various other abandoned buildings and businesses—monuments to the legacies and ongoing impacts of nuclear and petrochemical industries. After a day spent visiting the Weldon Springs nuclear waste repository, a nearby “smoldering event” (a fire that has been burning in a toxic waste dump for years), and the mounds of coal byproduct near Cahokia, our subsequent trek to the neighboring planned suburban communities was particularly jarring. New Town at St. Charles, Missouri, is a Truman Show–like development on the floodplains of the Missouri River north of St. Louis and Ferguson. The town aspires to present itself as if everything is normal and fine—a seemingly willful denial of the environmental and social injustices that surround it.

Objects gathered by Andrew Gustin on the recently flooded “Island 7” near Kentucky Bend. Field Note by Tom Turnbull A mix of shells and polyethylene “nurdles” gathered on a beach in the Chemical Corridor, Louisiana. Field Note by John Kim

Moving from the scale of landscape to the more immediate, human scale, the places we camped were scattered with an assortment of technofossils and the ubiquitous detritus of other lost plastic toys and shoes (including the Star Wars Landspeeder pictured earlier). Many of the river islands do not have much trash, but some have masses of floodwater-deposited plastic. At the even smaller scale of things that one could cup in one’s hand, between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, we gathered shells mixed with small bits of the plastic feedstock used to make all the disposable marvels of consumer capitalism. Embedded into the sand and sediment, these small, high-density polyethylene beads (referred to by locals as “nurdles”) reflect the thorough mix of natural and unnatural on the Lower Mississippi. We also sampled sediment along our entire journey to test for the presence of microplastics, another geological marker for the Anthropocene.

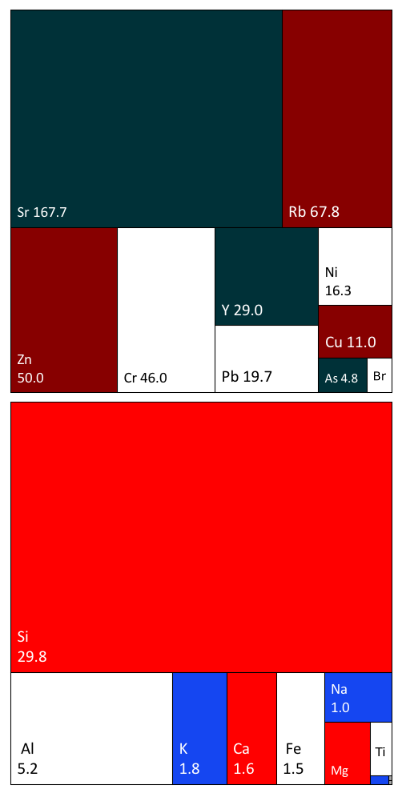

Diagrams showing the trace elements (top), including lead, strontium, and arsenic, and major elements (bottom), such as silica and aluminum, found in river sediment between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Field Note by Simon Turner

Besides microplastics, we found microscopic manifestations of the Anthropocene in the constituent and trace elements present in the collected sediment samples. River Journey participant Simon Turner’s diagram of one such sample shows significant levels of strontium, lead, and nickel. The microscopic transformations of the river are also reflected in the chemical composition of the water itself, with the steadily increasing mix of chemicals, sediment, and plant matter dissolved and suspended in the water.

The Lower Mississippi Delta as tabula rasa. Field Note by Amalia Lequizamón

In contrast to this muddy mix of biogeochemical and multi-scalar imbrications in the river, we found engineers’ attempts at representing and understanding the river to be jarringly simple and antiseptic. We encountered the river engineers’ challenge to understand and control the river in grand form at Louisiana State University (LSU), where we visited the Center for River Studies’ latest river model. It is a space-age representation of the Lower Mississippi River, used by hydrologists to understand flooding, sediment flow, land loss, and the impacts of different potential engineering projects on the river and its delta. Many of the weary and muddy travelers found the model troubling in its erasure of human communities and its assumption of a godlike mastery and omniscience about the river.

The fearsome symmetry of the massive engineering and river control infrastructure on the Lower Mississippi, here at the Bonnet Carré Spillway. Field Note by Joe Underhill

The further downstream we traveled, the larger the river grew, as did the corresponding river control infrastructures. Above New Orleans, the Old River Control Structure and the Bonnet Carré Spillway are part of the massive system of flood control structures that stretches from St. Louis to the Gulf of Mexico. The spillway is an acknowledgment of the need to give the Mississippi some breathing room—but always on terms dictated by the City of New Orleans and local petrochemical interests.

Steven Diehl reading some of the displays in the model jail cell at the Angola Museum gift shop at the Louisiana State Penitentiary. Photo by John Kim

With some trepidation and discomfort, the group stopped by the Angola Museum gift shop—as strange and dystopic a manifestation of the modern forms of capitalist slave labor as one is likely to find. The museum is part of the Louisiana State Penitentiary, which is built on the site of the former Angola plantation, giving rise to the prison’s nickname of Angola. It houses predominantly African American inmates who are living the legacies of slavery, racism, segregation, and mass incarceration, referred to as the New Jim Crow. In a twisted modern form of the display of Roman gladiators, prisoners perform in the “Angola Rodeo” for the amusement of locals.

View from the parking lot outside the ExxonMobil Baton Rouge Refinery, where several river travelers were detained and questioned by local police and company security officers. Field Note by Joe Underhill

Between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, we visited the Norco and ExxonMobil refineries. These were some of the first large-scale oil refineries in the country, combining German chemistry knowhow and American entrepreneurship into a living monument to the fossil fuel age. Each site is a thorough merging of the state and petrochemical capitalism, and they are highly guarded spaces. When several curious river travelers decided to walk around the Baton Rouge Refinery, even though they were outside the fences, they were stopped, put in the back of a police car, extensively questioned, and threatened with arrest for trespassing.

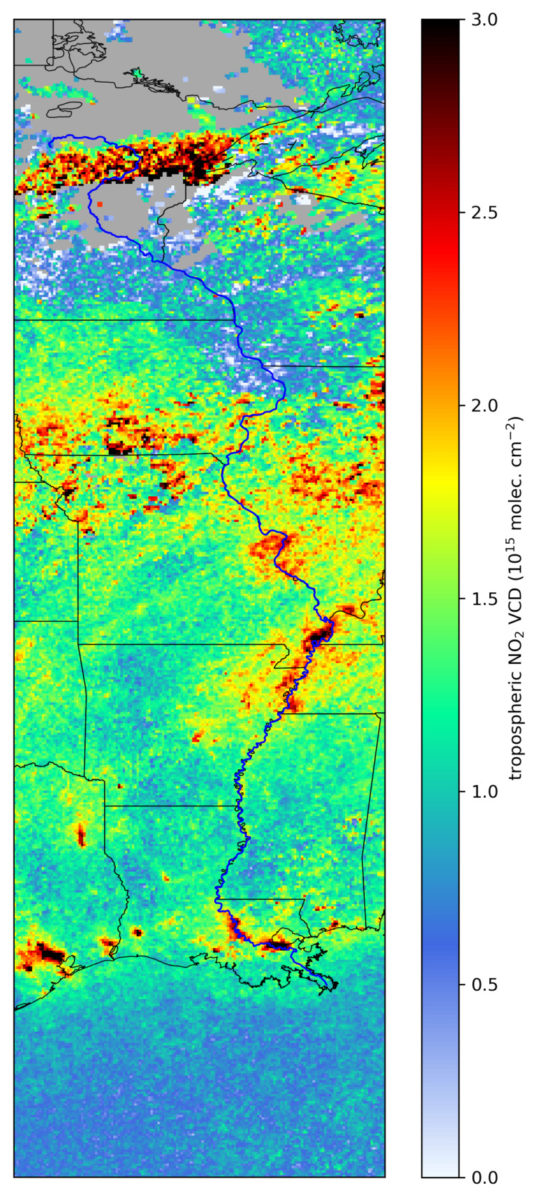

A satellite view of the concentration of nitrogen dioxide in the air above the Anthropocene River. Field Note by Christoph Rosol

From the vantage point of outer space, other patterns of the Anthropocene emerge along the twists and turns of the Mississippi River. As the river travelers paddled past an endless string of factories and cities, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Germany, using satellite sensor data, monitored the air quality along the route. Remote sensing of atmospheric nitrogen dioxide showed particularly high levels in the Chemical Corridor between New Orleans and Baton Rouge.

The dissolving delta and dead oak trees as viewed from the last remnants of land near Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana. Photo by Joe Underhill

All of these alterations reach their apotheosis at the Gulf of Mexico, where the reengineered delta begins to eat itself alive. The Louisiana Delta loses approximately one acre of land an hour, the result of many factors. The average sea level has risen about five inches in the twentieth century, and by 2050 it is predicted to rise another ten. Serious risk of flooding remains, should there be a sufficiently large storm surge or heavy rain—as the residents of New Orleans’s Lower Ninth Ward know all too well. There are predictions that globally by 2050 there will also be hundreds of millions of refugees and internally displaced persons as a result of climate change. We saw direct evidence of the beginnings of this in New Orleans and along the Gulf Coast. The photograph above shows land loss along the Louisiana coastline, as cemeteries, homes, and farmland sink into the sea—an evocative geographical form of Karl Marx’s description of the “creative destruction” of capitalism, in which “all that is solid melts into air.”

The unavoidable petrochemical entanglements; an arts and music festival sponsored by a major oil company. Field Note by Benjamin Steininger

The interconnectedness and urgency of the Anthropocene necessitates the breakdown of the false barrier between learning and living, between campus and world. We are teaching and learning and doing research in institutions and on campuses that are themselves part of the anthropocenic problem—fossil-fuel intensive, consumerist, located on land stolen from Indigenous Peoples. There is some hypocrisy in studying sustainability and the Anthropocene while continuing to consume resources and emit greenhouse gasses at a frantic pace, and fund schools with endowments invested in oil companies. At the same time, we have to recognize that a complete about-face is not possible. In philosopher Theodor Adorno’s words, “there is no right life in the wrong one.” That said, there are certainly some ways of life that are better than others.

Given the emotional toll of immersing ourselves in the ecological and social destructiveness of the current era, an Anthropocene curriculum entails breaking down the barrier between the intellectual pursuit of knowledge and the personal pursuit of well-being. This is not new to today—people have obviously studied grim topics in the past—but the current set of challenges are troubling in new and different ways. This is all the more reason to acknowledge the emotional and psychological dimensions of these subjects, and to explore ways to find ways to inoculate ourselves against the effects of dealing with these realities, building up coping mechanisms and new ways of being. We need to find the right combination or sequencing of different experiences; that is to say, a balance of exposure both to the problems and to the solutions. We will need to find the emotional intelligence and strength for this work, cultivate pragmatism to solve problems on the ground, and foster flexibility and resilience. In order to find our way home-in-the-world, we have to see how much we can simplify our ways of life and strip away the accoutrements and technological conveniences of modernity, both to reduce our ecological impact and to more fully experience the realities of the Anthropocene while still taking care of ourselves.

Finding balance in the Anthropocene life

Our campsite on an island in the Mississippi River near La Crosse, Wisconsin. A way of living with enough comfort while being connected and immersed in the world. Field Note by Christoph Rosol

The modern extractive capitalist activities and systems of wealth production that have led us into the Anthropocene—the consumption of massive amounts of energy, construction of structures and infrastructures to keep us “safe” and “comfortable,” production of all the various modern conveniences and labor-saving devices, development of elaborate and resource-intensive urban environments—have produced the highly controlled, artificial environments that both separate us from the natural world and make many lives easier and more comfortable. Much of the history of modern, Western, settler-colonial capitalism can be read as the quest for greater levels of control over the world (controlling othered bodies, water, energy, food production, and capital, keeping out disease, enemy invaders, “undesirable people,” and so on). This system has gotten very good at creating a sense of control over its surroundings. The results are planetary dysfunction, climate change, extinctions, and personal dysfunction, depression, anxiety, and malaise. To a large degree, these systems are mirrored, replicated, and refined within the structures of higher education.

One goal of an Anthropocene curriculum is to “get outside” of these structures and resource-intensive ways of being. To a degree, this means living with fewer barriers between us and the world. Such an arrangement facilitates our own awareness of and understanding of the Anthropocene in all its unpleasantness. By removing these barriers, we are brought into conversation and cohabitation with the amazing array of humans and species—kin—that share this planet, and, in the process, we become more fully alive. This does not mean we should or can remove all barriers—the complete removal of barriers is found only in death and our complete dissolution into the world. Human life requires us to be reasonably warm (or cool) and to avoid the mosquito bites, sunburn, poison ivy rashes, and other unpleasantries that can come from life out of doors. The trick is to find that the balance between being connected to the world and being exposed to danger or great discomfort. There are always trade-offs here, but it seems clear that a large part of the Anthropocene problematic is the excess of barriers.

An Anthropocene curriculum, then, requires some redefining of the “comforts of home,” not as the sterile isolation of the modern home but as the vitality and connection found in being at home-in-the-world. To the extent that our ecological (and often social) impacts are directly tied to our comfort level, this new way of living will require giving up things, and living with less control and comfort than we have become accustomed to. Some technological fixes—solar energy, electric cars, high-efficiency buildings, and so on—may allow us to have our cake and eat it too. But, at least in the short term, there is no way we can reduce the total destructive impacts of the modern economy and way of life without some fairly radical shifts. We should not underestimate the political, social, and cultural difficulties of such a shift—humans are generally attached to their comforts, love labor-saving devices and new gadgets, and there is a massive marketing system promoting all of this.

The question of how much we can or should we give up came up at various points along the river trips, as we collectively faced the physical challenges and discomforts of a life that entailed a significant decrease in the control and conveniences of home-in-the-Capitalocene. For the most part, we used our own bodies for labor, with the result being a per-person carbon footprint that was a small fraction of a typical American’s. We were sheltered from the elements by a few layers of clothing or our sleeping bags and the two thin layers of ripstop nylon that constituted our tents at night. We got muddy, bathed in the river, were bitten by various blood-sucking insects, and experienced at various times sunburn, straight-line winds, scattered flurries, and flash floods. As we as individuals struggled with these conditions, we had to think about how much discomfort we were willing and able to endure.

Undertaking the River Journey is not a matter of doing penance for our extractive and overconsumptive sins (although there is inevitably an element of the morality play here). Such an experience is most constructively seen as engaging in an awareness of the true “cost of living,” as it includes a wide array of social and environmental impacts. It is then our responsibility to minimize these impacts and in a basic sense just clean up our messes. It is important to keep in mind that this kind of low-impact living should not be imposed on those living at the margins—people for whom the exposure to the vagaries of the world is a daily reality, often with high costs. The global poor, seeking relief from the hardships of poverty, have every right to improve their standards of living and enjoy the benefits of “modern life.” Those in the Global South and Indigenous and other marginalized communities within Western nations will need to find their own paths, with allyship consisting largely of the hegemonic rich white folks getting out of their way, addressing the historical injustices, and dismantling the structures that continue to do slow violence in those communities.6 The issue here is not to impose strictures on the poor; it is crucial that there is agency and choice in this process of making a home-in-the-world, not some imposed hardship of poverty or displacement. But for those who can and do choose to live at home-in-the-world, it then becomes possible to see value, joy, and a way forward through this kind of liminal, balanced way of life, walking as lightly as we can on the Earth, transitioning as quickly as we can away from the fossil-fueled economic system, and in the process undoing some of the psychological harm inflicted by civilization’s discontents.7

How hard do we push ourselves in order to address these societal transformations that the Anthropocene now requires of us? There is no one particular answer to this question, other than to say that we must cultivate an awareness of the issues and engage in an ongoing discernment of how far to push ourselves. The appropriate balance will depend on the individuals that make up a given community, and the cultural context. For our particular experience of facing the Anthropocene on the River Journey, besides the challenge of safely navigating the actual river (an inherently dangerous activity, in and of itself), we needed to travel through this landscape with a level of self-awareness about all the above-described emotional dynamics. A key dimension to the experience is the attitude and group culture with which it is approached. If the attitude is one of unrelenting pessimism and despair, the experience reflects this. Approached with some level of optimism or hope for change, the experience is markedly different.

In the context of spending time on, and learning from, rivers, this optimistic approach amounts to aspiring toward something akin to the state of flow8 or being-in-the-river, in the sense of being fully immersed in the complex and multifaceted realities of life, rather than being separated from them. On these river expeditions, such a state of flow is often the case, both literally and figuratively. Finding the balance between stagnation and exhaustion, between those things that we cannot change and those that we can, between boredom and terror, we sought a kind of Aristotelian golden mean. Not unlike the current negotiations around safe spaces and trauma on campuses and in classrooms, we need to find the right amount of challenge—that is to say, a right balance to challenge our ideas and assumptions but not cause harm or trauma. In expedition language, we must try to find that space known as one’s “challenge zone,” which exists between the comfort zone and the panic zone.

An embodied theory of education and life calls us to get our neurons firing, our muscles pumping, our senses alive. This idea of being “fully alive” is worth taking seriously, even as it ironically entails being closer to death—more exposed, vulnerable, at risk in the world. If the Faustian bargain of modern consumer-extractive capitalism is that we have numbed and anesthetized ourselves, retreated to the mall and self-hypnotized ourselves in front of the digital phantasmagoria of a billion high-def screens, this journey into home-in-the-world offers an alternative where we can connect with the world and our fellow human beings, with a much greater chance of saving ourselves. This kind of “aliveness” includes a thorough connection with and awareness of the beauty and wonder of the world, a connection to a community, a grounding in the body and the pleasures and joys that it brings—and a sense of purpose and meaning in one’s life. We experienced all these dimensions, at various points and to varying degrees, along the river.

Imagining a way home

Can you imagine a way

Canoe, to carry us home?

Dig, dig into the water

Dig, dig into the water

Heave-e-oh! Heave-e-oh!

Heave-e-oh! Heave-e-oh!

—A round we sang on the river

The psychoaesthetics of the Anthropocene are generally dire, verging at times on the apocalyptic. The landscape’s palette is bleak and dark and raises again the question of how to move through this space and to live with these grim realities while still maintaining one’s sanity, agency, and any sense of hope. Any number of different responses to these kinds of modern stresses can arise—escapism and retreat, religion, drug use, therapy, action, humor, getting lost in abstraction. Which mix of these is most conducive to making some progress in addressing the Anthropocene problematic, particularly in regard to a university curriculum?

These anthropocenic states of mind—ranging from anger to dysthymia to depression to trauma—were ameliorated through the kinds of experiences we had on the river. Because, in addition to all the “fuckery” perpetrated by the forces of reactionary patriarchal heteronormative fossil-fueled consumer capitalist neocolonialism, there is also a great deal of life force, fierce love, and diverse resilience out there. There is the unending flow of energy from the sun, the never-ending flow of rain from the skies, the inventiveness and ongoing diversity of life forms and genetic material, and the richness of cultures that we will need in order to imagine a way home. The world has been harmed, but it is still a huge world. Humans, despite our increasing numbers and impact, are still but a small part of the whole. On these journeys it was clear that the river was bigger than us. And it provided us with many moments of solace, inspiration, and joy.

Camp on Wolf Island, Missouri, October 14, 2019. Photo by Joe Underhill

In the midst of all troubling encounters described above, we would also have evenings like the following. On the approach to Wolf Island, situated below the confluence of the Mississippi with the Ohio (between Cairo, Illinois, and New Madrid, Missouri), we had expected that we would be able to paddle directly to the landing at the head of the island, since the river was just below flood stage. We found, however, that the wing dam at the head of the channel was still just above water, requiring a last-minute strenuous paddle against the current to clear the rocks. Having succeeded in safely rounding the wing dam, we made our way, with tired limbs, to the landing on a wide expanse of sandy beach. We pitched our tents and the dinner crew began cooking as the sky turned gold and pink and purple in the sunset (pictured above). As always, the firewood was gathered. Nell pulled out a textbook and got some studying done. Carlina went for a swim in the chilly water. The moon rose, bright enough that we observed faint rainbows in the airborne ice crystals that framed it, which we decided to call “moon dogs.” In this silver light, we heard coyotes in the distance as we sat around the fire telling stories and singing a few songs as Audrey played the guitar.

The human-powered travel past hints at a low-carbon future—wind turbine blades being shipped north. Field Note by Joe Underhill

Despite everything that has been done to the Mississippi, the river is still home to paddlefish, a species that has been in its waters for tens of millions of years. There are rich forests of silver maple and black willow, oyster mushrooms to be foraged, “river angels” who humble us with their generosity and hospitality. There are signs of change, restoration, revitalization, decolonization. On the River Journey, we experienced not only the noise of the machine but also the contrasting quiet flow of the water, and on a few occasions, barges passed by us loaded not with coal or soybeans but with wind-turbine blades (pictured above).

Chi-Nations Youth Council sharing their stories of efforts to reclaim land and a home in Chicago. Field Note by Temporary continent.

The many examples of resistance, agency, and creativity provided solace in the midst of the otherwise grim terrain. We were inspired by the stories and work of Chi-Nations Youth Council, a group of Indigenous youth in the Chicago area who are working to reclaim space within the city (pictured above). We had the opportunity to witness the dramatic assertion of a new form of postcolonial agency in the reenactment of a 1817 slave rebellion in Louisiana (pictured below). We toured the remarkable habitat restoration at the site of the former Badger Army Ammunition Plant in western Illinois. We shared meals that connected in various ways to the river and local landscapes, like our “Edible Narrative” meal in St. Louis. We “ate the river” as part of the “Asian Carp Convivial,” a celebratory meal that highlighted the work of a local business that harvests the invasive bighead and silver carp from the Mississippi River and markets them both in China and the US. Although not everyone found the fish particularly tasty, it was a joyous and creative way to reframe our relationship to the introduced “invasive” species in the river. And we saw the radical rethinking of local autonomy and decolonization of Cooperation Jackson, the black-led experiment in self-government in Jackson, Mississippi. From a very different political perspective, we likewise experienced the radical hospitality of the staunchly Republican family at Poche Park in Pauline, Louisiana, a riverside campsite they created on the batture in the corridor between Baton Rouge and New Orleans in which air pollution and cancer rates are some of the worst in the nation. There our generous hosts brought us pralines, cokes, beer, and stories, showed us the gators in the nearby slough, and invited us back to their houses for showers and stories of life in the shadows of the sugar fields and petrochemical factories.

Reclaiming agency by rewriting history. Dread Scott and reenactors of the 1817 slave rebellion in New Orleans, Louisiana. This particular revolution was televised. Photo by Joe Underhill

Throughout the journey and our direct confrontation with the Anthropocene River, the river travelers found themselves responding intuitively and instinctually to take care of themselves and each other, with humor, play, music, dancing, and the occasional post-paddle shoulder massage circle. Through it all, we traveled under the ceiling of home-in-the-world, which repeatedly awed us with its splendor and the graceful, spiraling dance of the migrating white pelicans, even in the midst of the signs of destruction and land loss. The river travelers were hungry for these experiences, longed to be part of them, and missed them terribly once the journey was over.

The river travelers demonstrate what to do after a long day of paddling through the Chemical Corridor, Louisiana. Field Note by Joe Underhill

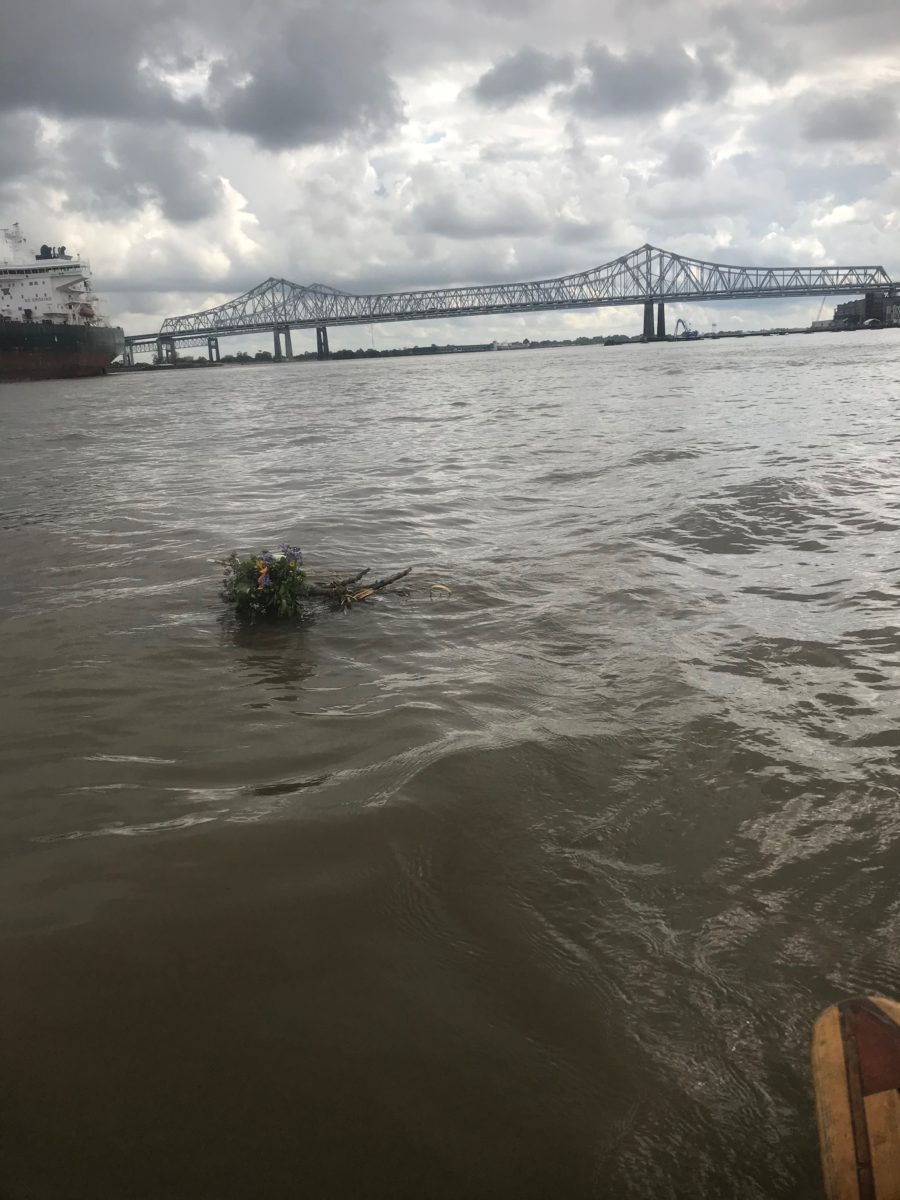

One of the most powerful and meaningful activities that evolved over the course of the trip were the aforementioned water blessings, introduced to us by Saundi Kloeckener, which we held on Sunday mornings. These were healing moments of quiet reflection that grounded us, connected us to our feelings and to each other, and brought us closer to the community of water protectors and river citizens that spans from the headwaters to the Gulf of Mexico. This ceremonial, even spiritual, component of the experience was incredibly important. At our last camp above New Orleans, Ben gathered black-willow branches and flowers and created a ceremonial bower. As we paddled into the port of New Orleans, the deepest and most polluted stretch of the Mississippi, we launched the ceremonial raft of flowers with the blessing “Travel well, flowers. Travel well.” Dwarfed by the passing oceangoing freighters, it was a powerful sign of hope, a spontaneous expression of our persistence and of the need for beauty in the midst of the Anthropocene.

Our offering to the river as we paddled into the French Quarter of New Orleans. Photo by Joe Underhill

In the end, when the group reached the Gulf of Mexico, the river began to feel wild again. The travelers noted how it began to feel like the headwaters, as if we had come full circle. The disappearing delta, and the dying trees, were poignant reminders of the realities of the Anthropocene, and out in the gulf itself were hundreds of massive oil-drilling platforms, frantically working to extract the last remains of the fossil fuels used to power the processes that are destroying the delta. But despite all this, there was still the splendor of the evening sky, and there were hints of what it would take for us to find a home in this troubled world.

With thanks to Audrey Buturian-Larson, Steven Diehl, Nell Gehrke, Fiona Shipwright, Nick Houde, Jaclyn Arndt, and Emily Knudson for helpful feedback, suggestions, and edits.

Select Bibliography

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper, 2008.

Edgeworth, Matt, and Jeffrey Benjamin. “What Is a River? The Chicago River as Hyperobject.” In Rivers of the Anthropocene, edited by Jason M. Kelley et al., pp. 162–75. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2018.

Hanh, Thich Nhat. At Home in the World: Stories and Essential Teachings from a Monk’s Life. Berkeley, CA: Paralax Press, 2019.

Haraway, Donna. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin.” Environmental Humanities, vol. 6 (2015): pp. 159–65.

Kagge, Erling. Silence in the Age of Noise. New York: Pantheon, 2017.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed, 2015.

Kress, John W., and Jeffrey K. Stine, eds. Living in the Anthropocene: Earth in the Age of Humans. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2017.

Morton, Timothy. The Ecological Thought. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Nixon, Rob. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013.

Tsing, Anna. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibilities of Life in the Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017.

Underhill, Joseph. “What We Learned from the River.” Open Rivers, no. 6 (Spring 2017): https://editions.lib.umn.edu/openrivers/article/what-we-learned-from-the-river/

Zolli, Andrew. Resilience: Why Things Bounce Back. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013.