Nordic Fauna Seen in Nature

In my research I am particularly interested in botanical collections and collecting spaces. Why do we have them, where do they come from, and how have they played (an ever changing) part in shaping the world and our shifting understandings of it? So when it came to choosing an anthropogenic landscape, it was always going to be some form of collection, but rather than revisit the botanic gardens, herbaria, and databases where I usually spend my time, I thought I would venture into a space that lies outside the scope of my research at present, but in many ways functions in the same way.

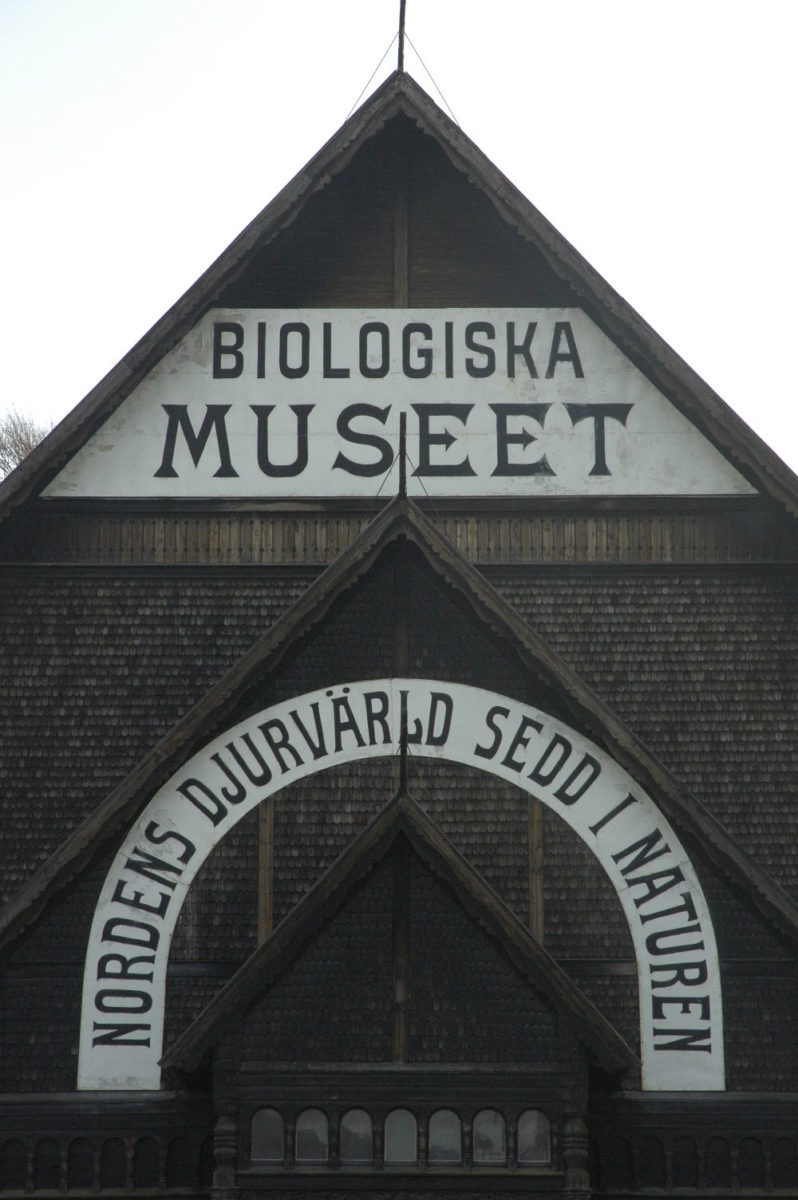

The Biological Museum in Stockholm, built in 1893, is designed rather like a traditional Norwegian church in what is now the Royal Djurgården Nature Reserve. Approaching the museum, one cannot miss the text that frames the ornately carved entrance: “Nordens Djurvärld Sedd I Naturen” (Nordic Fauna Seen in Nature). Enter, and nature awaits discovery. But what is this “nature”?

I think the key word here is “Seen.” There is an important difference between the claim of presenting fauna seen in nature and fauna in nature, but in a science that privileges sight above the other senses, the difference can be overcome through the art of verisimilitude—whether through the hands of the taxidermist and founder Gustaf Kolthoff, or of the painter Bruno Liljefors.

The museum is similar to an observatory, where the animal kingdom is gathered, represented, and fixed in time and space. As such it functions as a microcosm, representing in this closed space all northern fauna. Unlike the cabinets used in most natural history museums, the specimens are mounted in a 360-degree diorama, so that the visitor has the experience of being immersed in the landscape.

Like the bird-watcher, then, I will zoom in and begin with the small.

This is a bullfinch, the harbinger of snow. At a glance, it looks alive, about to tilt its head before flitting off to another branch. It looks real. The taxidermist’s art (re)captures the bullfinch in a possible moment, as in a photograph, so we can study its fine beak and beady eyes up close and at length. But we cannot observe its movements.

The landscape beyond jars a little, remote against the familiarity of the bullfinch. It requires more of the observer—a little imagination, a certain suspension of critical faculties, and a selective viewing, for instance, that the bullfinch is seen not through the kitchen window, but through the glass of panel 15. It is visibly locked. The padlock, marked with an egret, designates a clear boundary between “nature out there” (enclosed in the museum) and the observer.

This is, of course, “nature” as conceived in 1893. It is completely devoid of human traces, with the exception of the remains of a wooden crate on the beach.

On the ground floor, there is a small exhibition of bird species that have moved in and joined the Swedish fauna since the museum was built. An update, in effect. The sign emphasizes that (unlike the diorama, we might add) nature is not, in fact, static:

“Our fauna is in constant change. This might depend on human effects such as hunting, toxins, drainage of marsh lands, climate change etc. The changes can also be natural, as species expand to new territories. [. . .] Over time species disappear from Sweden while others immigrate and establish populations.”

Nonetheless, the dioramas are impressive technologies of representation. “Fauna Seen in Nature” seems justified, if we accept that “nature” is that which can be captured, externalized, contained.

In this museum-as-observatory, the human viewer is in the centre, surrounded by, yet separated from, a rendition of nature that is both controlled and fully knowable through the act of looking.

At the same time, in a sense, it is the viewer who is encased, surrounded by dead species, whose glass eyes are no longer able to meet her gaze. There are two cabinets in the entrance: one with claustrophobic-looking bears, and another with the hare-grouse. It is a curiosity, yes, but in the context of genetic engineering debates, for instance, it seems prophetic of an anxiety about what the limits to controlling nature could or should be.

At the heart of this observatory, this panopticon, is the emergency exit (“Emergency exit only!” in Swedish, English, and Russian), an elevator that makes me think of space shuttles and elaborate emergency-exit plans of planetary proportions. For me, this fixed, crafted landscape expresses the irony of a belief in the separateness of humans from the rest of the world coinciding with the age of the Anthropocene.