Notes Toward a Karachi Ecopedagogy

Sensing the Ephemeral Rivers

Where are we in relation to nature? And what does it mean to sense, to know, to anticipate, to expect, to witness? Situated in the urban concrete landscape of Karachi, Pakistan, artists Shahana Rajani and Zahra Malkani propose an “ecopedagogy” that entails awaking ourselves to a network of relationality, not to the landscape alone, but also to communities devastated by the ecocidal impulses of the state and the expanding development and displacement in the area. Rajani and Malkani argue that Karachi’s history and presence is not only marked by this violence and erasure, but by a rich history of resistance and refusal—battles to defend the ecological body of Karachi that constitute an ancient and ongoing pedagogy.

In the concrete urban landscape of Karachi, our relationship with nature is primarily one of denial and domination. When the land speaks to us, loud enough that we have to hear it, it always seems to come as a surprise, a rude awakening. During the last monsoon, in August 2020, the city flooded. Karachi’s seasonal rivers—carved out and built into by real estate developers and state officials drunk on high-end housing projects and spectacular infrastructure—returned, as they do, remembering and reminding, flooding over gates and busting through concrete. However much we bury and build upon it, the landscape demands to be known. The relationship between the city dwellers of Karachi and the ecology of this land has been marked by violence, both slow and spectacular, and a profound alienation. Our upcoming course at Karachi LaJamia seeks to move beyond this painful disconnect into recognizing and inhabiting, with care, our profound entanglements and shared destinies with this erased ecology.

The city is imagined as the other to nature, outside and beyond nature, a site that overcomes the petty limitations of nature to truly realize the power and potential of humankind. Like most cities, Karachi has been built on a relentless annihilation and enclosure of land, unceasing expansion, and the continued devastation and displacement of the communities that have long inhabited it. In the idealized urban dream of Karachi, there is no indigenous nature, no indigenous life—the sand is from Dubai, the trees from Riyadh, the grass from the US, topped off with an Eiffel Tower replica from Paris. Truly a world-class city, Karachi today is on the frontlines of the climate crisis—with floods, water shortages, and heat waves becoming increasingly routine. At the heart of this crisis is a systematic forgetting, erasure, and denial of Karachi’s indigenous ecology, indigenous communities, and indigenous knowledges. Our course seeks to remember, acknowledge, celebrate, connect with, and sense this ancient ecosystem we call Karachi.

Where are we in relation to nature? What is this ground that holds us? Who walked it before us? Where does our food come from? Who grows it and under what conditions? Where does our concrete come from? Where does our water come from? Who fights for it? How can we visualize Karachi and ourselves within these webs of relationality that sustain us and that we systematically deny, desecrate, and devour? Deep contemplation of the topography of the city destabilizes and unravels, exposing all the fallacies prevalent in the dominant narratives of Karachi. Sensing and connecting with the land may bring us closer to a long process of unlearning this relationship of domination and alienation from the land. In this text, we contemplate one particular ecological form in Karachi for all the pathways of wisdom and insights it opens up for us.

The River

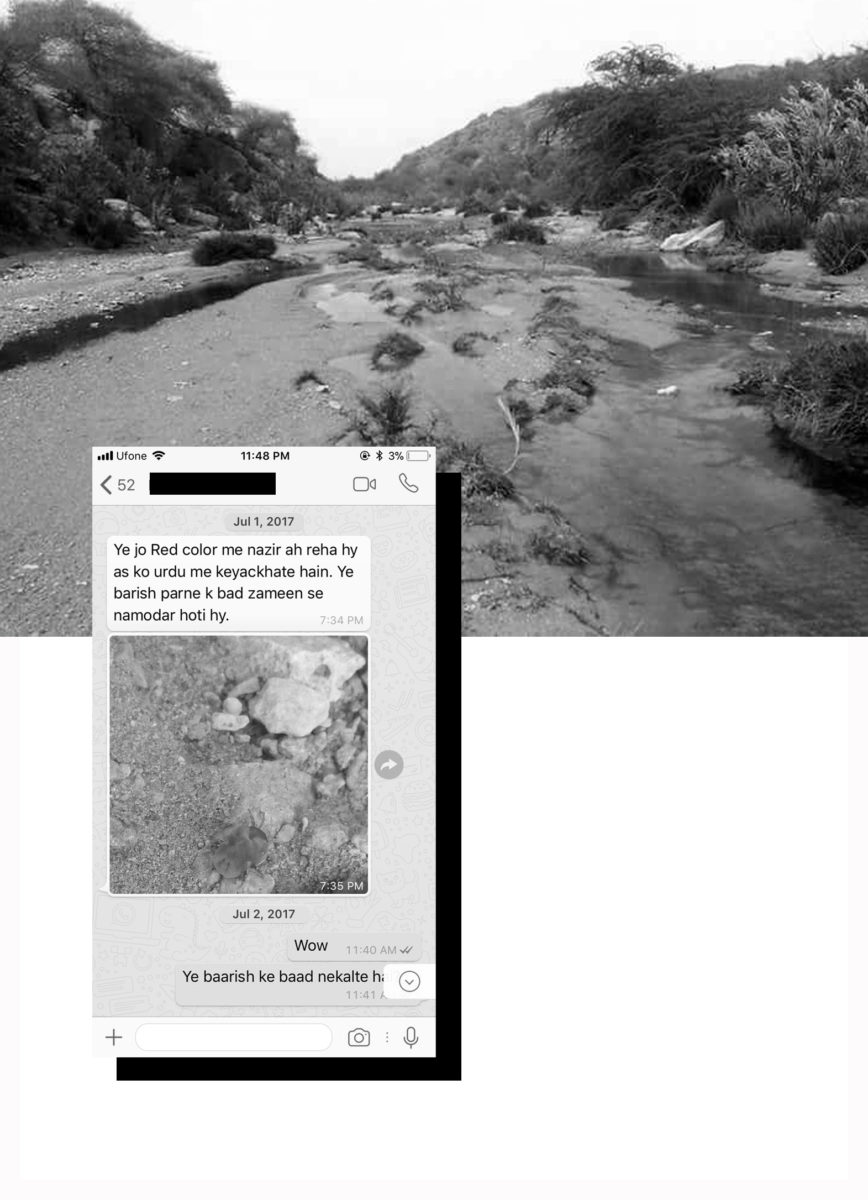

Excerpt from Exhausted Geographies II, an artist book by Shahana Rajani, Zahra Malkani, and Abeera Kamran, reading Karachi through emergent and decaying infrastructures, disappearing ecologies, and architectures of militarization. The excerpts included here are from the booklet Zikr, reflecting upon and mapping the disappearing rivers of Gadap. Image by Shahana Rajani, Zahra Malkani, and Abeera Kamran © all rights reserved.

We begin with the seasonal, ephemeral river—a mystical ecology. The ephemeral river comes and goes, flowing in and out of our consciousness. What does it mean to sense, to know, to anticipate, to expect, to witness the seasonal river?

Located on the western bank of the Indus River Delta, Karachi is built around and upon a river ecology. In a dry, desert landscape, the river becomes a central infrastructure for livelihood and sustenance. Sindh, the province Karachi is located in, is named after the ancient river Sindhu, and its patron saint, Jhulelal, is an avatar of the river, seated on the aquatic lotus flower, perched atop the mysterious palla fish. River songs, river worship, and river myths abound in this region. Rivers haunt the imaginations of mystics—bodies of water, in all their various scales and moods, are encountered and sought as divine, mysterious, miraculous places in so many sacred and mythological traditions. Water is always engaged in some kind of alchemy, always shape-shifting. It softens everything it touches, reflecting, mirroring, and transforming. It disappears before our very eyes, and emerges out of nothing.

On maps of Karachi, ephemeral rivers and ecologies remain unseen. These cartographic representations reduce and flatten rivers and hills to seemingly inconsequential interruptions upon the surface of a land imagined as a tabula rasa. Such maps also bear no traces of the indigenous communities who have lived with these ecologies for generations. Villages, homes, agricultural fields, pastoral lands, and sacred geographies are denied representation on survey maps and have disappeared from public view. The blank spaces in these maps efface; they insinuate that there is no history here. They convince us of an untouched, empty land: ready, waiting. These violent practices of mapmaking, carried forward today by state and real estate developers, remind us of a long history of forgetting Karachi’s river and delta ecologies. This systematic forgetting has been central to the making of the city as we know it today.

In contrast, indigenous narratives of the city routinely feature, and even center, these ephemeral rivers that ebb and flow. Ephemeral ecologies mark time, make manifest cycles of nature, appear as invitations for livestock, agriculture, and play, and bring with them gifts of abundance. However, these river imaginaries do not exist within the one-dimensional cartographic register. They live in and through the memories, experiences, and practices of people and communities. Temporal river ecologies refuse the fixity of the cartographer’s map, mark the failures of the map form, and challenge the colonial vision that conceived of land as distinct from water.

The seasonal river, as it brims and floods, appears and disappears, in all its uncontainability, overcomes the blankness and boundaries of the developer’s map. The river demands a longue durée connection. It reminds us that to sense, to understand, to know, and to live and work with the land is a durational, multigenerational practice. A deep and grounded connection with nature is impossible without indigenous knowledge—knowledge accumulated over many generations of careful observation and symbiotic relation with the land. This knowledge must be accumulated and passed on across lifetimes before one can even begin to sense and comprehend the rhythms of nature. Today, these knowledges are devalued, degraded, erased, and ignored across the city—by state officials, developers, and urban planners and by activists and academics alike. The ephemeral river is an invitation, a leakage that lays bare all the cracks and crevices in our knowledge of the land.

Excerpt from the booklet Zikr, reflecting upon and mapping the disappearing rivers of Gadap. Image by Shahana Rajani, Zahra Malkani, and Abeera Kamran © all rights reserved.

Ephemeral rivers abound in Gadap Town, an indigenous neighborhood on the outskirts of Karachi. Gadap was once considered the “green belt” of Karachi and was a primary source of food and water for the city. More recently, the communities that have lived in Gadap for generations have been at the forefront of environmental resistance in Karachi for the past eight years, as they resist the demolition of their homes and the displacement of their communities at the hands of the state-backed real estate mega-development organization, Bahria Town. In 2016, Karachi LaJamia in collaboration with the Gadap-based Karachi Indigenous Rights Alliance organized a course titled “Gadap Sessions,” bringing together a range of students, activists, and researchers from across Karachi to witness, document, and investigate ongoing processes of accumulation by dispossession on the peripheries of our city. At the center of our pedagogical approach was Francisco Gutiérrez and Cruz Prado’s concept of “ecopedagogy,”1 where pedagogy is understood as a practice of connection, collectivity, community, and care—not only with one another but also with the ecology and environment in which we are situated.

As we moved through this landscape, where development and infrastructure are unleashing vast dispossession and erasure, communities spoke of the dozens of seasonal rivers and waterways that exist here that are being wiped out and built upon. While Bahria Town advertisements and maps invoke Gadap as a barren wasteland awaiting the gift of development, local communities alerted us to the seasonal rivers and nourishing landscapes that have sustained life here for centuries. Roz, Kaccha, and Chakor are the Balochi names given to the streams and other places where water would collect after rains in the Pahwaro mountain of Gadap. Padaraii Chhab was another place on the mountain where every year after the rains, people from nearby villages would go live with their livestock. In Balochi, padar means “temporary,” and chhab means “a small waterway.” These placenames reflect the way people engage with and inhabit their land as well as the centrality of seasonal waterways in practices of migration and settlement. The names enable a remembering, an intergenerational sharing of knowledge and intimacy with the natural landscape. Since they are not visible to the eye, sensing these ephemeral rivers requires a familiarity with the forms and flows of the landscape and demands close attention to the textures of the ground—the silt and sand, pebbles and rocks—formed over centuries of intermittent contact with water. The residents of Gadap warned of the floods that await Bahria Town if its developers build into the land with little care or knowledge of this landscape—a warning that proves prescient across Karachi every monsoon, as we experience devastating floods in sites that were once rivers and now are concrete.

While real estate megaprojects like Bahria Town have decimated the natural landscape, disappeared indigenous landmarks and waterways bear witness to the dense interconnections between people and nature, to a practice and politics of care and respect for the ecology and the natural orders of landscapes. Even in the aftermath of occupation and devastation, indigenous communities across Karachi remember each river by name, where it came from, where it went, and when to expect it. Herein lie the keys for reconstituting our relationship with the land in Karachi.

Excerpt from the booklet Zikr, reflecting upon and mapping the disappearing rivers of Gadap. Image by Shahana Rajani, Zahra Malkani, and Abeera Kamran © all rights reserved.

If we sense and listen, the sounds of the rivers echo within our homes, too. This city of concrete is built from mining the riverbeds of the Lyari and Malir Rivers. Over the past few decades, 60 billion cubic feet of sand and gravel have been illegally lifted for construction purposes from seasonal riverbeds in Karachi’s rural areas. This unlawful practice of sand mining has led to irreparable erosion and depletion of rivers and fertile land. While the Karachi Master Plan of 1975–85 envisioned that 85 percent of Karachi’s agricultural needs would come from its immediate hinterland, today these lands can barely sustain fodder. Urban development in Karachi has been built not only on expropriated rural land but also out of it. The river and the land became the very raw materials needed to construct the concrete city. In that sense, its capacity for and the inevitability of its decay and doom is encoded into the very material of these infrastructures. Try as developers and politicians might, the temporality of infrastructure cannot overcome the life cycles of nature.

As Karachi has grown and expanded, an endless labyrinth of infrastructure has followed, razing centuries-old networks of rivers already ravaged by sand mining. The most recent example is the new infrastructure project the Malir Expressway, designed to flow alongside the Malir River to connect gated communities like Bahria Town in Gadap to the city center. This new road will occupy and devastate 700 acres of fertile, agricultural land along the river. Such roads that emerge onto and cut into the natural landscape have an anywhere-everywhere texture of smoothness. This smoothness of the urban ground is highly political, as it forces us to relate to our bodies and the environment in particular ways. In reducing friction, paved roads and concrete surfaces allow us to forget the very ground we travel on, the ground that holds us, obscuring and erasing. To refuse the road as a securitizing concept is to sense and listen to the mutability of the ground, its variations and vulnerability, its complex textures and topography, narrating history and cosmologies.

The floods and flows of these rivers, cyclical and tentacular, transgress boundaries and respect no borders. They trace and connect pathways, lineages, networks in a dance of relationality. They defy the colonial obsession with containment and borders and the sharp distinctions between self and other that mark urban life. The Lyari and Malir Rivers rise from the Kirthar Range, imbricating Karachi within a larger ecosystem and social world, disrupting its imagined boundaries. The city’s unabated growth floods and clogs these rivers—as well as the Indus Delta to the east—with industrial waste and raw sewage, poisoning the water and ravaging mangrove forests and marine ecologies. The destruction of the delta ecology, in turn, contributes to the drying of the seasonal rivers and the devastation of villages, lives, and livelihoods as the sea swallows up the delta, displacing and pushing floods of climate refugees into the city. In 2019, farmers and fisherfolk from across Sindh marched to Karachi to protest and bring visibility to the desecration of the Indus Delta, the fifth largest delta in the word, highlighting the centrality of Karachi in the planetary ecological crisis.

To truly contemplate and reach toward the ephemeral rivers is to enter into the cosmographical dance they map across the surface of the city, imbricating those who live in Karachi within an ancient, planetary, multispecies web of relationality. Awakening ourselves to this network of relationality means, necessarily, bearing witness and attending to not just the landscape alone but also to the communities—indigenous groups and refugees—devastated by the ecocidal impulses of the Pakistani state and the ecocidal frameworks from which Karachi has been, and continues to be, built. As much as Karachi’s history and present is marked by this violence and erasure, it has also been marked by a long and rich history and tradition of resistance and refusal. From the ephemeral rivers to the coastal islands, from farmers to fisherfolk, battles to defend the ecological body of Karachi are an ancient and ongoing pedagogy.