“Planting a Seed is a Revolutionary Act”

A Blues Epistemology for the Anthropocene?

In this reflection on experiences in Natchez, Mississippi, Jason Ludwig, whose research explores racial capitalism and environmental injustice, describes how the town’s Black history—for so long suppressed in favor of an antebellum heritage tourism economy—has been asserted through the efforts of local activists. It is only through paying attention to these histories, he argues, that the intersecting Anthropocenic relations of extraction, enslavement, and inequality are revealed. Ludwig puts forward what writer Clyde Woods termed a “blues epistemology,” as a means of establishing the critical historical consciousness crucial for determining more just futures in the Anthropocene.

I: The View from Natchez

When I visit huge mansions

I run around to the back,

looking for the house

behind the house behind

the Big house where my origins

begin in this Republic.

— Sterling D Plumpp1

“Natchez was and is a segregated town,” explained Jeremy Houston, a local tour guide and historian. This Mississippi city with a population of around 15,000 is also an unusual starting point for any effort to conceptualize the Anthropocene. Compared to the dramatic scenes of resource extraction usually associated with this term, Natchez is a slow and quiet place—seemingly far adrift from the global march of unmitigated extractivism that has harbored climactic and geological catastrophe on a planetary scale. Nevertheless, as Jeremy led our group of curious students, artists, and researchers through the town in October 2019, I found myself wondering: what exactly, then, can Natchez teach us about the Anthropocene?

Although once home to thriving paper mills and rubber plants, Natchez has since been left behind by an industrial economy that has sought cheaper labor abroad. Today the city depends for most of its money on a tourist industry that encourages visitors to spend day (and night) on grounds once worked by enslaved people. The city’s verdant meadows are dotted with grand manors sporting equally grand names like Longwood or Rosalie Mansion, former cotton plantations, and homes of cotton planters that have been converted into museums or bed and breakfast inns. These all aim to display to visitors to the city the wealth and opulence that once belonged to its antebellum, slave-owning elite. In Natchez today, tourists are invited to not only eat dinner on tables once owned by those who made their fortune in the trade of other human beings, but also— if one is so inclined—to take “haunted” Halloween tours through their plantation grounds, their bedrooms, and even the cellars of their mansions (although visitors are left to imagine for themselves the identities of the tattered and tortured ghosts who might be stalking the halls of the master’s house).

If the concept of the Anthropocene points our attentions to the future, Natchez on the other hand feels like a town designed to send visitors on a trip back through time. But as Jeremy was at pains to point out, the image of the past that the average tourist receives is an incomplete one. While Antebellum Natchez certainly was one of the country’s wealthiest cities, its grandeur and wealth was produced by the labor of enslaved people—none of whom could enjoy the benefits of these riches. Theirs is the history you will not receive while staying at a bed and breakfast, Jeremy explained. And that is why he and other Black residents have taken it upon themselves to tell the other half of the city’s history—the story of its Black past. They have invested many years labor into doing so, erecting several placards and monuments throughout the city, marking sites of importance to the history of Black Natchez. These include slave markets, blues clubs, and the homes and business places of post-emancipation Black community leaders and civil rights activists. Jeremy himself has played a prominent role in recovering this long-ignored past, publishing a multi volume history of Black Natchez, working as a docent at the city’s African-American History Museum (opened in 1991), and founding his own historic tour company.2

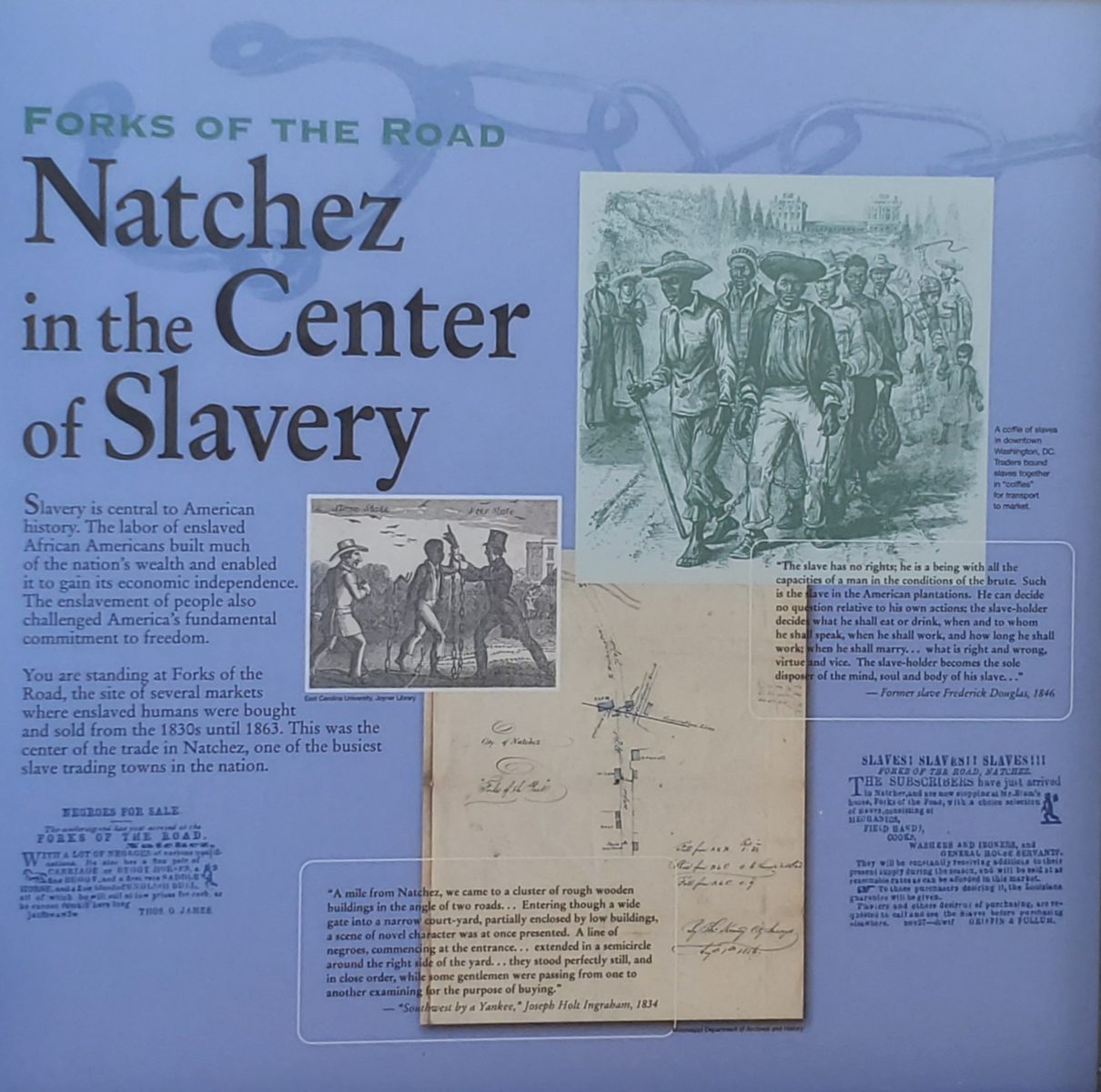

The institutionalization of Black history in Natchez has only been possible thanks to long battles fought by local activists. The memorialization of the Forks of the Roads slave market is a case in point. The market, located at what was once a busy intersection along the city’s eastern border, was founded in 1808 by the slave traders Isaac Franklin and John Armfield. Until 1845 it was a principal trading post in the global exchange of human bodies, with thousands of enslaved Africans and their descendants marched out on display under the brutal Mississippi sun, to be gazed upon by prospective buyers as well as a curious public. At its peak, around 500 enslaved persons were sold per day at Fork of the Roads, making it the largest Southern slave market outside of New Orleans. Such prodigious commercial activity was fueled by a developmentalist ideology that tied the economic growth of Natchez and the surrounding region to the expansion of the plantation economy as well as to the brutal bondage and exchange of enslaved bodies undergirding it. Its chief slogan—which made today’s thriving plantation tourist economy possible—is captured in an old advertisement for the Forks of the Roads market (reproduced in facsimile on one of placards that stands at the site today): “Buy More Negroes to Raise More Cotton to Buy More Negroes.” And so on and so forth.

A historical placard at Forks of the Road. Photograph by Jason Ludwig

Despite this history, the grounds where the Forks of the Road market once stood remained empty of any historical markers until 1998 when local community members campaigned to memorialize the site. After a protruded battle with city leaders, who were worried that such actions might taint the city’s reputation as the civilized and aristocratic “Jewel of the Mississippi” (which, they feared, would harm the tourist industry), the campaign succeeded, leading to the erection of placards that narrate the history of Forks of Road. Today, visitors to the site will find on display iron chains that once held enslaved people waiting to be sold into the brutal economy of Mississippi’s cotton kingdom.

That this history remained silenced for so long is all the more egregious considering its relevance to present day concerns. With his profits from slave-trading at the market, Isaac Franklin started his own cotton plantation in nearby Baton Rouge in the 1830s. Displaying a cruel and sardonic wit, he named it after the country from which he had imported most of his enslaved workforce: Angola. Nearly two hundred years later and in its current guise as the largest and most notorious maximum-security prison in the United States, Louisiana State Penitentiary, the Angola Plantation continues to operate as a site geared towards extracting maximum value from Black bodies in bondage.

That such connections to the past remained for so long hidden from public memory is no mere accident. Nor is it surprising. A plethora of scholars have shown how, like murderers hiding the bodies of their victims, dominant institutions expunge the histories of violence that enabled their ascension in order to cover their hegemony under a veil of normalcy.3 In Natchez, the image of the city presented by the tourist industry depends to a large extent upon such silencing of the past. As the work done by Jeremy and others who have sought to recover the history of Black Natchez shows, however, marginalized groups can and will contest the monopolization of historical narration.

The lessons this offers towards understanding the dynamics of the Anthropocene is that just like fossil fuels, just like cotton, just like tourism, history has a political economy too. And just as rethinking and reshaping our dependency on oil and coal is crucial for building a more livable future in the Anthropocene, it is also vital that we develop new forms of critical historical consciousness and institutions of public memory that place the injustices of the past on trial. Such work, which Jeremy and others in Natchez have long been engaged in, is an ineliminable step towards building a more just world. As the poet and native Mississippian Natasha Trethewey has written, confronting the challenges of the future means first “reckoning with our own blindness and erasures.”4 Put another way, reckoning with the Anthropocene requires not mistaking huge mansions to be our history, and searching instead for the stories hidden away in the house behind the house behind the Big House.

II: Singing the Blues in the Anthropocene

One scholar whose life work equated to just such a colossal effort to uncover lost Black histories is Clyde Woods. In his writings on the history of the Mississippi Delta, Woods argued that the alluvial soils of the region gave birth not only to the logics of domination that justified the racial violence and ecological exploitation still prevalent in the United States today, but also to the most cogent forms of critique and resistance—what he named the “blues epistemology.” Woods describes the blues epistemology as a Black intellectual tradition vested in collective deconstruction of the “plantation relations” that first destroyed Black identities and aspirations during enslavement, and which have continued doing over 150 years after emancipation. As a mode of knowing and expressing anguish at the Black past, indicting the injustices of the present, and imagining and building towards a more just future, the blues epistemology can be understood as oriented around social and personal investigation of two critical questions: “How did we get to where we are now” and “How do we get to where we want to be?”

And as those preserving the history of Black Natchez have shown, the blues epistemology and the forms of survival and resistance it has engendered have always been present in the city and the surrounding region. Its presence can be felt today in the Natchez African-American Museum, where one can read the stories of the formerly enslaved who sought to build new lives for themselves while caught within a freedom that was not truly free; or about the musicians and writers, from Papa Lightfoot and Richard Wright to Anne Moody and the Ealey Brothers, who sought melodic and literary languages with which to express blues wisdoms; or even about Wharlest Jackson, whose life was stolen by a car bomb because he dared to speak up and fight for Black equality. Their stories all attest to the fact that as long as plantations have stood in Natchez, there have been voices courageous enough to indict the violence and exploitation that they stand for.

Richard Wright exhibit, The Natchez Museum of African American History and Culture. Photograph by Jason Ludwig

These voices must be amplified and their insights must inform every conversation concerning the Anthropocene. If the term “Anthropocene” conjures up apocalyptic images of ecological catastrophe, mass precarity, and the fragility of human life, then which other voices can guide our thinking about these issues other than those who have for generations engaged in critique and resistance against systems of violence and exploitation? Woods expresses this idea perfectly,5 stating that future political and economic movements must take strides to

celebrate and valorize the millions up upon millions, living and dead who met the regimes of destruction with unshakeable dignity. In the same vein, the lands, rivers, streams, air, plants and animals of the region must be restored to their sacred status. Until then, ‘every hill and molehill,’ every blade of grass, every flutter of the flag, and every note that is played must be contested.

From the viewpoint Woods offers us, the Mississippi Delta and its surrounding areas emerge as pre-eminent sites for understanding the historical forces that have shaped the Anthropocene. The blues epistemology offers the conceptual means for comprehending how this region never truly was the heart of an “empire of liberty,” as Thomas Jefferson once dreamed of it, but was instead the epicenter of the nightmare that was American slaveocracy. Thinking the blues in the Anthropocene means attending to the history that tracks the expropriation of territories along the Mississippi, from Native populations and the radical reshaping of these lands into an ever-expanding regime aimed at extracting maximum value from land and from brutalized Black bodies. The tendrils of this regime stretched far beyond the banks of the river, its cotton, and capital traveling across the Atlantic to fuel the industrial economies that European powers would later apply towards colonizing much of the globe.6 Seen from the blues perspective, then, the plantations standing along the Mississippi River represent the foundations of the modern hierarchical world-system, and signify the violences that announced entry into the Anthropocene.

Only once the constitutive role that these historical violences against nature and people played in the development of the modern world is acknowledged can the important work of constructing more livable futures begin in earnest. This is the foundational truth to which the blues epistemology has always attested. The pantheon of blues thinkers enumerated by Woods—and indeed, Woods himself—demonstrate an express commitment to developing a new social order centered on the liberation of subjugated lands and people. No figure expresses this ideal better than Fannie Lou Hamer, who founded the Freedom Farm Cooperative in Sunflower County, Mississippi in 1969. Believing that true freedom would remain unattainable for the Delta’s Black population so long as wealthy white planters monopolized land, Hamer started the farms in order to promote Black self-reliance in the region. For Hamer, the Freedom Farms expressed her philosophy that land should be communally-owned and that Black survival in Mississippi depended on seeking the necessary means for “channeling legitimate discontent into creative and progressive action for change,” whether it be through practicing sustainable agricultural or organizing political movements.7 To this end, the Freedom Farms produced food intended to feed Mississippi’s impoverished and struggling Black families, while also offering affordable housing, educational opportunities, and various other services.

Although a lack of funding meant that the Freedom Farms were short-lived, such an experiment in envisioning and enacting a more socially and ecologically just world is instructive for our present moment, which is plagued as much by social injustice as by looming environmental catastrophe. Indeed, Hamer’s work at the Freedom Farms has continued to serve as touchstone and guidance for those concerned with sustaining Black life amidst the future challenges presented by the Anthropocene.

III: Black and Blues Futures

Like Jeremy fighting to uncover the past of Black Natchez, others in Mississippi are reclaiming the legacy of Fannie Lou Hamer and the blues tradition in their efforts to develop a more liberatory Black future. The relevance of the blues epistemology to conceptualizations of the Anthropocene is most apparent in Mississippi’s capital, Jackson. In the “City with Soul,” Cooperation Jackson is organizing Black and Latino working-class communities towards building an environmentally sustainable, worker-owned cooperative. So far, this consists of the Freedom Farms (named after Hamer’s cooperative), community maker-spaces, and a land trust upon which efforts are underway to develop worker-owned businesses and housing. Across these sites, the group seeks to develop the institutions and infrastructures necessary to sustain Black life in the face of the planetary devastation threatened by the Anthropocene.

This work draws heavily on the inspiration of previous generations of Black radical thinkers and activists, ranging from Hamer to Kuwasi Balagoon, the radical Black poet and anarchist. The Cooperative’s current work also builds upon the legacy of the Jackson-Kush Plan, a generations-old Black re-imagining of the city of Jackson and the Mississippi River Valley that envisions the region as a catalyst for a sweeping transformation the living conditions of Black Americans. The plan envisions the creation of a Black-led New Afrikan Republic in Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Tennessee that models itself after the Ancient Egyptian Kushite Civilization, with the Mississippi River serving as the fertile analog to the Nile.

Through their work, which blends Mississippi’s long tradition of Black critical thought with expertise in twenty-first century digital tools, Cooperation Jackson applies the blues epistemology towards developing what the historian Rayvon Fouché has described as a “black politics of technology,” a radical reshaping of technological processes in a manner responsive to Black needs. The result is in a broad vision of what radical Black future-making in the Anthropocene might look like.8

The cooperative’s work is foremost concerned with addressing the resource deprivation that is a direct legacy of the ecological devastation and underdevelopment wrought by the plantation economy on Mississippi’s landscape. Kali Akuno, one of Cooperation Jackson’s founders, has written that the history of Mississippi’s development “has fundamentally been contingent upon the extraction of natural resources such as timber… and cash crop agriculture, such as cotton, tobacco, sugarcane and rice, which were primarily sold as international commodities.”9 However, with the nineteenth-century transition from a global capitalist system structured around agricultural commodities to one structured around fossil fuels, formerly monocultural economies like Mississippi, lacking the capital and infrastructural networks of more economically-advanced regions in the United States, have since been locked into a state of resource scarcity and underdevelopment.

The burdens of this underdevelopment have largely been fallen onto Mississippi’s Black population. Despite the abundance of food across the United States and of agricultural land in Mississippi itself, working-class and impoverished Black populations in the state face a variety of food-access deprivations. This food scarcity, an ongoing legacy of the plantation economy, has left Black communities in Jackson and the surrounding region with little to no access to fresh and healthy foods. Addressing this racially-stratified scarcity motivates Cooperation Jackson’s work, which applies new and sustainable technologies towards continuing Hamer’s efforts to advance black food sovereignty in the region. Their plans to achieve this include the creation of an Eco-village in the heart of the Downton Gateway section of West Jackson—a “comprehensive, interconnected and interdependent supply and value chains…our own network of cooperative farms, processing centers, food hubs, compost and soil generators, food processors, canneries, grocery stores, etc.”10

The cooperative seeks to further develop Black resource sovereignty by building the material and infrastructure for the Eco-village with tools created in their Centers for Community Production—maker-spaces that use open source sharing and 3D printing in order to develop sustainable, worker-controlled manufacturing. Through work like this, Cooperation Jackson contributes a black radical vision of technoscientific practice in the Anthropocene that imagines possibilities extending far beyond the visions of global “sustainable development” discourse, showing how new tools can be used not just to improve profit margins while cutting carbon emissions, but in order to catalyze the democratization of the economy, the transition to a sustainable economy, and the empowerment of vulnerable Black communities.

Like Hamer’s Freedom Farms, Cooperation Jackson’s work is as much about feeding impoverished Black Mississippians as it is about seeking out and enacting a more just world. Such undertakings locate the Anthropocenic task of reshaping of our relations with the natural world as inextricably intertwined with the need to address and undo the legacies of centuries of racist violence. As Sister Imani Bridgeet Olugbala of the cooperative has put it: “planting a seed can be a revolutionary act.” Through following this insight and earnestly engaging with histories of violence, as well as those of Black resistance, perhaps we can plant the seeds necessary to sustain and cultivate more just and ethical forms of life in the Anthropocene.