Relational Repair

A conversation on relationship, reparation, and reconciliation

In this edited transcript, Jeremias Herberg, a political sociologist whose research focuses on former mining regions in East Germany, and Rebecca Freeth, a researcher and dialogue facilitator working with Reos Partners in South Africa, reflect upon different understandings of repair. Drawing upon experiences from their research contexts, they consider the importance of tending to the “connective tissues” of relationships, the difference between innovation and repair, and the conditions required for truly restorative justice.

Rebecca Freeth

“Repair” hasn’t really been a big word in my vocabulary, but, in you and I preparing for this, I feel like it has entered my vocabulary in a way that I really appreciate. I find it a very productive word. My practice has lots of other words that start with “re”, such as “renew,” or “reimagine,” or “restore,” or “restitution.” “Repair” seems to be a more decisive term, both in terms of what’s possible, and as a recognition of brokenness. If we use other words, like “restore” or “reimagine,” it suggests that something’s wrong, but not necessarily broken. And so I’m starting to think about my work through this lens of repair. I was actually a bit shocked by realizing how much I see as broken—in my work, and in my world. It was quite a stark reflection on the state of the world through my eyes.

Jeremias Herberg

When you see a lot of damage around you, and probably many people do, how do you determine with others or by yourself what is in need of repair or what is irreparable?

RF

I work as a facilitator; I work on projects where there are particular situations that are problematic, and somebody presents themselves as a “problem owner,” saying “this thing”—such as structural racism in organizations, or gender-based violence, or food insecurity—is a problem and can you help us address it?” Often the problem people present is one version of it. The way we try and work with it is to get as far below the surface of the problem as possible, to stay curious about what else is going on there: what’s invisible, and what’s perhaps the source—or closer to the source—of the problem as it presents itself.

But you work in a very different context, in an academic context, and so I’m wondering: how does the word “repair” feature in your own academic work or practice?

JH

One quite fitting example is when we worked with young coal workers in the coal district of Lusatia, south of Berlin.1 In the process of the government’s decision to phase out coal, they began to see a need of restoring their position in the region, in the job market, and so on. They are very aware of past damages that occurred in the same region for all kinds of reasons, especially the reforms after the fall of the Berlin Wall, but they have very little sense of how to gain their own perspective that isn’t inherited from former generations of coal workers. It’s in that—finding their own stance—that we as social scientists can, I think, help a little bit. In conversation, we can get to the things that they are already doing that are very concrete, local, and situated, such as organizing some volunteering effort or a festive event for their villages. Through place-based projects like these, local groups learn to repair the personal losses and social structures that are damaged from past or current conflicts.

The notion of repair seems, in daily life, to be reserved for concrete stuff, but the things that you and I repair—the examples we have just drawn out—seem to look at deeper damages that go beyond just superficial fixes. When repairing, how do you isolate the damages done and the tools you have? Issues rarely come alone, but you have to start somewhere. There are often multiple or combined crises, certainly in South Africa. So, where do you start?

RF

One way is to think about such situations as complex adaptive systems. The work of Paul Cilliers, a South African philosopher, has been enormously helpful to me. I learned Complexity Studies with him at Stellenbosch University. A system is adaptive; it’s not just waiting to be fixed. It’s already in motion; always in change. There are nodes and connectors. Our work is primarily at the level of the connective tissue of a system. The first thing is to simply observe some of what’s going on in that complex adaptive system—to try to understand it and remain open to what it reveals of itself—through inquiry, through watching, through interviews, through storytelling, through theater performance, etc. And then to work at that level of the connective tissue, which means working at the quality of relationships with others, or with ourselves, working with people’s sense of agency or sense of responsibility, or the flow of information, etc. You can think about this connective tissue at any scale—for example it can be intrapersonal, interpersonal, inter-organizational, or with the natural environment around us. That’s where there is potential for repair. The relational, the in-between, the connective tissue—that stuff never dies completely. It never gets damaged to the point of being irreparable, or at least that’s how I’m thinking about it right now.

JH

It makes total sense from a sociological perspective to say that society or social processes cannot be fully damaged, even though single nodes—individuals, things, or technologies—can look really damaged. But they’re involved in a process that is constantly evolving. You see your work as a facilitator of these relational connections, right?

RF

That’s right. Relational connections manifest in, for example, the quality of conversation—what we often call “courageous conversation” between people. When things have got difficult or stuck or stagnant, courageous conversation can reactivate that connection. It can bring new insights about what’s actually going on in the situation, or new self-awareness when we hear ourselves reflected back by others, or new energy to do something different. So, repair is this kind of reactivation or healing. I never used to use the word “healing” in my work, but the more I realize the extent to which we are dealing with traumas from the past, the more I realize that it is appropriate.

JH

I keep going back and forth on this word too. I don’t like the medical aspects or the notion of intervening into a body in order to heal it. But the agency of healing is quite complicated. If you look at the body, it has self-healing capacities. Biophysical processes often do: a soil that is beneath a burning forest, even if the forests falls completely flat, still has some life in it. There’s still some life in things that are deeply damaged, and “healing” recognizes that. “Repair” has this subject-object relation: it’s someone looking at something—it doesn’t need to be collective; it doesn’t need to be a long process—and saying “I will fix this now.” But “healing” needs some sensitivity to the autonomy of the thing that is healing or being healed.

RF

And if we were to apply the medical language of “cure,” then we are back in that subject-object paradigm of a linear fix. But “healing,” I agree, is more intrinsic. You can support healing, but the thing has to heal itself. I’ve just been on a call with somebody who works for an international NGO. Last year, we had been invited into this organization to work on issues of structural racism, which are pretty endemic across international NGOs. They were set up in a colonial era with this idea of white saviorism—and that is causing mischief at every turn. You can imagine what European white saviorism does to people here in South Africa, who have a much more accurate, lived understanding of what’s going on and what’s needed. And so we’ve been facilitating a series of conversations, and the real turning point, the game changer, in these conversations, has been about working with whiteness. It’s when white individuals, whether they’re South African or European or from wherever, can change their behavior. And—let me make it personal as a white person myself—when we can change our behavior as white people and stop acting out of the old scripts of whiteness and these implicit assumptions of superiority and expertise and leadership, when we can change our behavior, and listen, rather than speak, and be patient, to see what else is going on before we interfere, and when we can acknowledge our power and privilege, and its impact, without falling into shame, when we can develop a new repertoire of behavior, then something else is possible.

So today’s conversation was with an older Black woman, a highly qualified nurse who has worked in this international NGO for many years, and has felt that she’s been hitting her head against the same issues again and again, and that she’s not been seen, and that her potential has not been recognized, and that she has not been able to advance through the organization. The last conversation involved the whole organization sitting in a large circle with Black staff members telling their stories about working in the organization, with white people just listening, without interrupting, defending and or denying those experiences. For this older woman, it’s been a very powerful experience for her to finally have her experience heard, acknowledged, the pain of it recognized, and then to receive an actual response—a “what can we do about this together?” kind of response. And then something new is possible in those relationships. The actual words that this woman used today—referring to a white boss—were: “She became someone else. She wasn’t the person who arrived.” That’s the novelty; that’s the possibility for change. And the relationship shifted. Not just because of the conversations we’ve facilitated, but because the woman was so determined to repair the damaged connective tissue of the organization.

How do you think about the relationship between repair and transformation and the possibility for something new? Do you recognize that in your own work?

JH

Yeah, conceptually at least. Listening to you, I was thinking about this conceptual contrast between innovation and repair.2 The twentieth century was often seen as the age of the new—it was the promise of a brighter future, although it clearly caused a lot of damage. But looking at your work on racism and postcolonial relations—and also my work on decarbonization and what’s happening in old industrial regions, coal regions, and so on—you could quite boldly say, it wasn’t the age of innovation, and it’s now the age of repair that we’re dealing with.

And those who had the agency of bringing the new to the world in problematic ways, I wonder where their agency is now in the repair process. Both of us are white people: is it that we now need to let healing evolve in some sort of relational sense? I feel sometimes that’s the easy way out: if everything is relational and emergent, my responsibility becomes quite vague, right? Or is it that we leave the responsibility to those who have suffered damages to now call out the best repair strategy? Which also seems problematic. How can someone be expected to lead the change that they actually want to see in the others, in those who have inflicted the damage? Or is it that we want to take the lead in the repair process, because we now realize something has been wrong? But that would be a reiteration, possibly, of the white savior syndrome.

RF

I think it goes back to tending the quality of relationship: that’s the place that needs attention. Once there is more self-awareness, and once there is more trust in that relationship, then you can try out things together. But as a white person in the South African context, I would always assume that I probably know the least about the situation. And so my job is to stay present and in relationship. It’s not to disappear and say, “this is yours to fix” or to fall back into the trap of thinking I’ve got the answer. The relationship itself has the potential to be the place, the vehicle, the locus, from which change can happen. Because I think that instrumental ways of being white have malnourished relationship. As I listen to myself, I realize I’m speaking about this in quite stark terms. Because that’s my reality in the South African context. So if I’m to do things differently, it has to be at the relational level, first and foremost.

JH

There’s also a case to be made for building institutions of what scholars call “restorative justice.” So not only punitive justice, or other forms of justice that we have institutionalized already, but also processes of resolution that involve those affected, the offender, the community, and so on. And to somehow build conventions, build knowledge, build places or professions that help us go through processes of restorative justice. That involves an active part on all of the people that have a role to play in the damage, good or bad. Maybe the processes of post-apartheid South Africa can teach us how restorative justice is done. Would you be able to report a little bit about your experiences in that area?

RF

I’m not an expert in restorative justice at all and I probably won’t be able to speak to that specifically, but I can tell a bit about the story of post-apartheid attempts at truth telling and reconciliation. Between 1996 and 1998, we had the hearings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the TRC.3

There, the emphasis was on people who were perpetrators of apartheid-era violations telling the whole truth, coming to the commission and volunteering what they knew. There would be an assessment of whether they had told the full truth. Usually, the person they had wronged was also present and also had a chance to speak, to tell their story. Often the survivor was the mother, the wife, the sister, who had lost a son, brother, partner. So first it was truth-telling and the possibility was there to ask for forgiveness. And then there was the possibility to offer forgiveness. None of these things were assumed. But the conditions were created for it. And it did actually happen in some quite profound ways. A summary of the week’s proceedings was televised every Sunday evening. I found it completely compelling viewing to watch people from either side of apartheid encounter each other in person. It’s one of those deeply human and rehumanizing experiences on both sides. Because if you’ve committed a violation, you get dehumanized. If you’ve experienced a loss or grief that deeply it can feel like it compromises your humanity too.

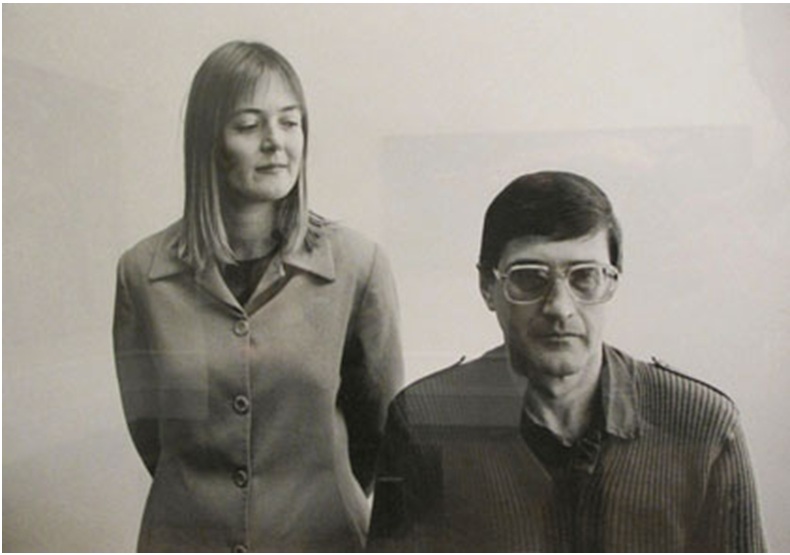

Jann Turner with Eugene de Kock, Truth Reconciliation Commission Headquarters, 1997. Kock was a South African Police colonel and assassin during the apartheid regime. Turner is the daughter of the prominent 1970s anti-Apartheid activist Dr Rick Turner, who was assassinated in 1978. Photograph by George Hallett, CC BY-SA 3.0

In the moment, it seemed to have very powerful impacts. But over the years since then all of the limitations have become visible. For example, there was a failure to prosecute people who applied for amnesty but didn’t receive it, as well as perpetrators who didn’t come forward at all. So people who had committed heinous acts of racist violence just got away with it. There was a promise of reparations, financial reparations, but they became smaller and smaller and smaller and ended up as a quite modest one-off payment to the minority of people who had appeared at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, but not to the millions of others who hadn’t. And that became a source of real bitterness. How do you acknowledge the need for material repair, where people’s lands have been stolen or livelihoods were taken away? How do you ensure that there is financial reparation, but in a way that doesn’t instrumentalize the relationship or make it transactional? It needs all of these elements to be really reparative. This is the challenge that the German government faces at the moment in Namibia. There’s been an offer of €1.1 billion in reparations for the Herero and Namaqua genocides. But there hasn’t been an apology and there is a lot of bitterness among Namibians about the way it has been done, which still doesn’t take seriously, at a relational level, what else needs to be repaired.

JH

It goes to show how many dimensions are necessary for a reparation process to be successful, or at least accepted as helpful by the people that suffered the damages. As you said, it has a material component. But it’s also a lot about timing. At what point do I condense this into a material offering, rather than continuing the dialogue? Or at what point is this not only about back-and-forth dialogue, but about me sending something to you, and accepting that you can do whatever with it and you don’t need to respond. So part of this seems to be bi-directional—you’ve talked about how everybody has a role as an active speaker. But, in some moments the dialogue shifts, and it needs to be really directional messages that acknowledge the power asymmetry, in the past and the present. It’s quite striking to me—if these processes are so key to current processes of change and justice—that there’s so little robust knowledge and institution-building around them.

RF

I think somebody who’s really worth mentioning in this regard is a South African psychologist called Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela. At the time of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission she was very involved in offering psychological support to people who gave testimony—including my dad, incidentally, who was a witness at the TRC. She has been unpacking that experience of working with these stories ever since. She recently founded The Centre for the Study of the Afterlife of Violence and the Reparative Quest. The term “reparative quest” acknowledges that repair is not a single action, and it’s not a product: it’s an arduous, probably long-term process and we have to quest for it; it’s something we seek out. Professor Gobodo-Madikizela has also used the language of “reparative empathy,” which I find really interesting. When she’s thinking about what needs to be restored, reparative empathy is that capacity to understand each other’s situations and hear each other and put yourself in the shoes of the other. For me, it’s helpful to think about three forms of empathy. One is cognitive: “I get it now, I can understand your reality better.” Another is emotional empathy, which I think is what Pumla’s talking about, to actually see our common humanity—as clichéd as that sounds—and to recognize the human being in the other. And then the third kind of empathy involves action, it involves doing something with your newfound cognitive and emotional recognition. I think this is the important thing. We have talked so much about the quality of relationship—that isn’t a passive thing, it requires action. It’s not like you just say, “well, we’ve restored trust and now that’s the end of it.” No, that then requires that we do something, in relationship.

JH

It seems like the large-scale repair processes we mentioned—be it in the post-colonial and environmental or other fields—require something visible, something that can be grasped, something that elevates the position of those who suffered the damage. Is “repair,” then, the right term for fixing things, for fixing relations? Can we scale it up and down as we’d like? Or should we reserve it for particular meanings? Is that a term that you would hold on to in the future?

RF

It’s probably not a term I will use in future because I think it can be so easily misunderstood, but it nourishes my understanding of my own work and helps me to see more clearly what is broken and the transformative potential. But, before we close Jeremias, I’d love to hear anything else you have to say about bringing it back to the Anthropocene and planetary repair.

JH

I mentioned the opposition of repair and innovation before and, in general, it seems to challenge me in my professional pessimism as a sociologist. Because, if we’re looking at this on a larger level, we could remain pessimists and see how much still has to be done. But I wonder if we actually do not already know quite a lot about how we can get rid of damaging technologies or institutions. We haven’t done so in a very sweeping way, of course, and it’s probably naive to think that we can now leverage a large-scale transformation that gets rid of everything that’s emitting greenhouse gases. But, for example, the ozone hole was a massive issue in the 1990s. And with a whole bunch of policies, alternative practices, innovations and so on, the chemical substances that led to that hole have been reduced quite drastically. 4 There are a few examples in the recent past or even longer ago where we have gotten rid of stuff that has been the cause of damage and have healed the damages. I would like to look at a couple of those examples—successful ones, less successful ones—and see if we can build a knowledge base. I think that’s also one of the lessons of the conversation for me is: repair is also about just trying to fix it. And you learn something, perhaps not for the very process that you’re in right now, but you learn about how to fix similar things, or how to use a certain tool, or how to position yourself in relation to people who have been damaged and so on.