Remnant Formations

East Coast Pine Barren Habitats of a Particular Ant

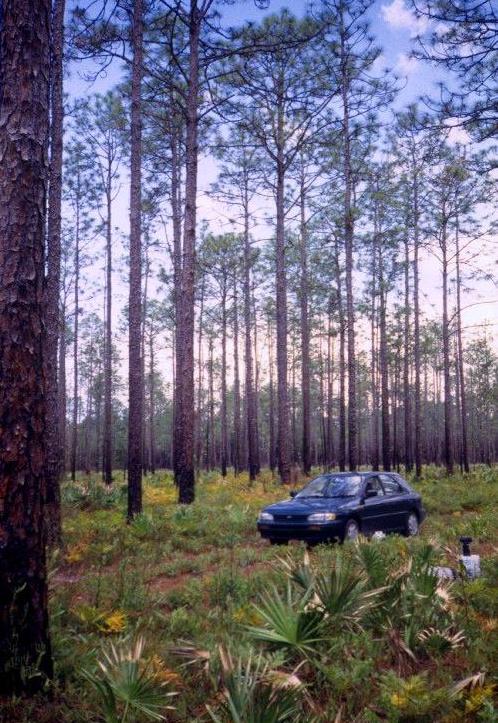

In the early 2000s I undertook the study of a particular ant, Pheidole morrisi, across a wide latitudinal gradient to study the effect of climate and other factors on the colony organization of this species. Three United States study sites were chosen for their pinelands, also known as pine barren ecosystems: one within a national forest in Florida; another within a state game land in North Carolina; and the last in an electrical utility company’s power line area in New York.

These sites varied greatly in the degree to which they were shielded from development and recreational use as well as in how they were managed in terms of ecosystem dynamics. Because pine barrens are sandy soil systems that are typically maintained by fire regimes, the nationally and state-regulated sites frequently conducted “controlled burns” to create something akin to the fire regimes that would otherwise occur naturally. However, because the US Army also used the state game-lands site for training purposes, unintentional fires sometimes occurred due to the use of artillery and weapons; likewise, spent ammunition littered the site. Managed forestry and logging were conducted at the publicly managed sites and I had to obtain national and state permits to collect ants there. The electrical utility company’s site in New York allowed no fire maintenance and instead mowed and cut vegetation to maintain space for the power lines. Access to these sites was not permitted, so my research collection was conducted without seeking permission.

Although all three sites were anthropogenic landscapes given their ecological management, it was because none of these sites permitted typical housing or agricultural development that they were especially attractive for my research: their lack of development meant that these were some of only a few places where my species of ant could still be found “in nature.” This was particularly evident at the electrical utility company’s site in New York, since these areas were among the few that were not either paved over or converted to lawns in that part of Long Island. An amateur ant expert, Ray Sanwald (Figure 1), was my local guide, as he has been for many international ant researchers looking to sample species native only to that locale. Ray has lived in this area of Long Island continuously for over seventy years. Over that time, his house lot, which had been at the far edge of agricultural land in the 1950s, in the intervening time has been engulfed by suburban development.

While I certainly altered the landscape with my own ant collecting (digging as deep as two or three meters to obtain the ants and removing the colonies in the process), Ray had begun to actually collect and relocate ants to a two-acre plot of land near his house to create a biodiversity sanctuary for native ant species that were in danger of becoming extinct due to habitat loss. Ray’s particular interest in “slave-making” ants and species of this group were of high priority for his singular conservation effort. He was very supportive and encouraging of my collecting because he saw my species as competitors to the slave-making ants that he was trying to preserve—anything that aided their removal was a positive change in his eyes.

There is no other person known to have the expertise Ray has with that local ant fauna, and this has implications for future study into the slave-making species, which are of great interest to a global group of researchers. Like the national and state forests, the Long Island Pine Barrens are garden versions of those that existed before. The habitats within the utility power line areas and similar sites present interesting cases in which patterns of otherwise uncontrolled urban and suburban development are interrupted, although often they function in support of those very forms of development they partially resist. Perhaps there is some very loose comparison to be made to various areas of “new wilderness” that result from a mixture of both management and conflict, like the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) or the Chernobyl nuclear disaster site—both of which are forms of inadvertent nature preservation born out of the Anthropocene.