Repair Is Broken

Toward Fixing Repair

In this essay, human geographer Louise Carver examines what is broken about neoliberal capitalist modes of repair in the context of the Anthropocene. Analyzing the logics behind “natural capital,” “offsetting,” “net-zero,” and “ecosystem services,” she shows how these terms are used to uphold modernist-liberal traditions rather than to substantively engage with or respond to the entangled environmental crises we are facing. It’s first necessary to fix repair itself, Carver says, if we are to become ready for what is emerging through and as the Anthropocene. Since while repair suggests looking backward, it is towards new possibilities that recuperative efforts must be directed.

“Acknowledging that the world is not there for us—that it has its own autonomy, separate from one’s own—requires giving up forcing definitions on it. Maybe ‘life’ is vital, emergent, productive. Maybe it is not. Maybe ‘the world’ can be put to work in manifold ways. Maybe not.”

—Resilience in the Anthropocene: Governance and Politics at the End of the World1

When I was around seven or eight years old, I sat at my first-floor bedroom window and repeatedly dropped a ceramic clown out onto the paving stones below. It was a measured act. I didn’t throw the toy but just extended my arm and released it to observe the fall and impact; I was both fascinated and delighted that it had not broken on the first try. When it finally did, the fun was immediately over. Regret, dismay, and shame ensured. A disfigured character that, although still recognizable, was strangely alien to me now that it was in pieces. My interest in the toy’s material integrity and resilience evaporated the moment I knew how many times it needed to be dropped to sustain critical injury. But there was something I was told later, as I presented the pieces to my mother for repair, that I recalled only while writing this essay: “You must be a scientist,” she said. The comment seems to capture an experimental drive to push limits until the point of breakdown that perhaps characterizes both the careless games of an inquisitive child and the cavalier norms of advanced technocratic liberal modernity. I suspect it was belief in adult authority or expert, technical capacity to repair what is broken that encouraged me to test this object’s strength in the first place. If we are careless, then we break things we value, merely because we think they can be put back together.

A reparative mode of production or securing the “work of nature”

Twenty-five years later, I attended an international conference called the World Forum on Natural Capital in Edinburgh with a group of critical geographers from the UK and Canada. We were there to document and observe ethnographically the dramaturgy of an international summit, which at least by European standards had come to epitomize the mainstreaming and enactment of efforts to value biodiversity and ecosystems within corporate and national accounting regimes. This event and others that are similar represents a broader configuration of institutional alliances intent on “putting things back together” across the splintered, broken, cracked, and ruptured natural capital stocks upon which delegates were being reminded their operations relied.2 “Natural capital stocks” is another way of describing the web of life and abiotic ecosystem relationships and exchanges, which form at least one (ultimately undecouplable)3 foundation for capitalist production. Repair of this critical infrastructure is now privileged in terms that affirm its functionality as central to value accumulation. Environmental repair and restoration here become a central component of corporate engagement that must be valued, priced, and traded through business operations.

Epistemologies of brokenness will produce their own reparative modes. Hence some of the reasons for attending this conference and other similar places over recent years include to observe how the “realness” of and consensus for nature as natural capital is feverishly invested in,4 and to trace how this idea is backed up with armies of consultants, policy frameworks, technical reports, governance programs, and sometimes recalcitrant sums of money. Such assemblages of environmental governance—from national governments, to corporations, to multi-lateral organizations like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services—are avowedly working to restore a capital base for economic life on Earth. Appropriately valuing resources so as to maintain and repair “natural capital” is necessary to secure the other side of the accounting ledger: the flows of “ecosystem services” that feed socio-metabolic cycles. Talk of natural capital stocks and flows of ecosystem services is now so pervasive that it is easy to assume these phrases have always been part of the environmental-policy lexicon. The old idiom “unable to see the wood for the trees” was invoked by World Forum organizers to highlight the difference in value potential between treating timber as a one-time (or slowly renewing) resource for consumption versus seeing standing, living trees as providers of bundled and stacked “ecosystem services” or “green infrastructure.” These “services” include, for example, providing flood management, carbon sequestration, clean water, and functional biodiversity. Green (land-based) and now blue (ocean-based) capitalisms embody this eco-modernist impulse through ideational and policy architectures that use value, pricing, abstraction, and accounting to convey that living ecosystems are worth more alive than dead. This is, after all, nature at “work”—producing valuable services for humans and their economies. The logic is one that famously allows the International Monetary Fund to declare the value of a whale to be US$2 million, given its carbon-sequestering appetite for phytoplankton.5 In the Anthropocene, this nonhuman labor class is increasingly compromised. It is reduced in its capacity to functionally perform its role of regulating, provisioning, and supporting the manifold cycles, formations, decompositions, absorptions, and purifications of biospheric activity. Its workers strain under the weight of growing anthropogenic geological, atmospheric, and hydrological agencies. The premise for capitalist repair, therefore, is to set about restoration of this capital stock. It is envisaged that this could happen by fully recognizing (pricing) the “work of nature” within growth paradigms such that bodies and cycles will sustain their reproductive economic functions. From this emerges the premise for expanding restoration “economies of repair,”6 characteristic of a growing reparative mode of capitalist production.7

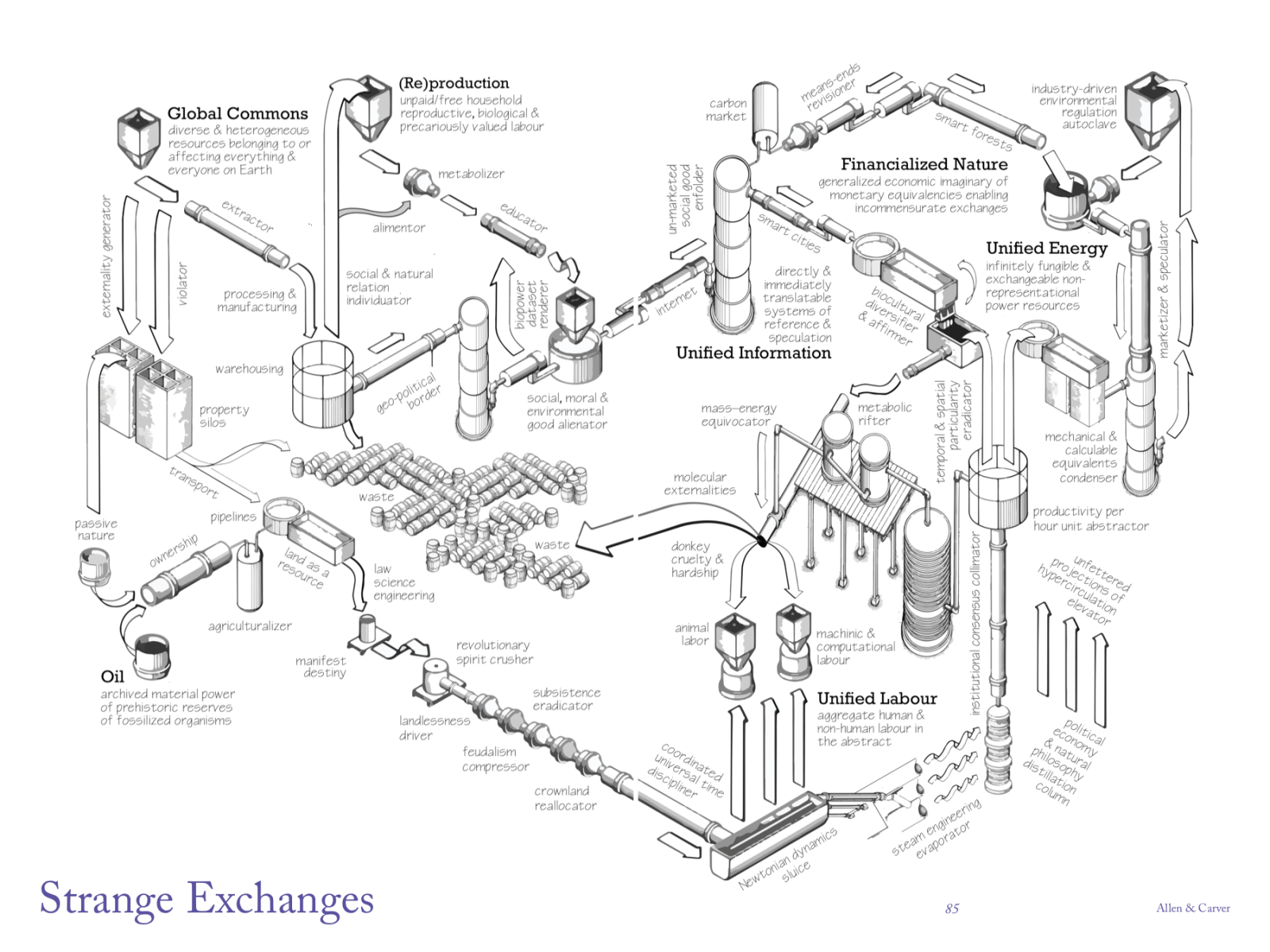

Historical dynamics and strange exchanges within machinic processions converging logics towards the reparative modes of capitalist production. Image by Louise Carver and Jamie Allen, from Strange Exchanges in an Almanac for the Beyond. Published by Tropic Editions © All rights reserved

Harm-led repair

Today, it is possible to “offset” carbon emissions, habitat impacts, and the loss of biodiversity, individual species, and hectares of wetland, alongside other definitive, bounded, largely fictional units of environmental value. Offsetting is economized repair in its most direct form. The logic is to precisely quantify and tie a reparative act to an environmental injury through an exchange mechanism in a way seen as neutralizing or even quantitatively inverting the harm (as it is registered in the accounts). Offsetting is the green economy’s fix, extending a pervasive and pernicious imaginary of nature as an artifact that can be technically and unproblematically mended. The hope is that the aggregate sum of harm and repair will deliver a net gain or net reduction of “value.” Yet often skirted over here is that the original damage will always exist but the repair may not.

One of the strange perversities of offsetting as a mode of environmental repair—premised on restoring natural capital value to compensate a harm—is that the harm comes to lead and pay for repair. In England today, new financing for the nature-recovery agenda is expected to come from biodiversity and carbon offsets from house and infrastructural developments. As the layers of accumulated system design stack up—exchange of this for that, according to one baseline or another—it becomes all too easy to lose sight of the bigger picture in the restricted view of arbitrary reference points, counterfactuals, and the constantly moving parts of a biosphere or biodiversity budget. This obfuscation is partly a function of valuation practices that equate geographically and functionally different natures and time frames. An energy company, for example, can purchase an environmental credit of “equivalent” biological, ecological, or atmospheric value to the harm it has presided over because it looks the same within the balance sheet of accounting. In this respect, offsetting can be and is used cynically to provide justification for damage to land or emissions that authorities otherwise would not have permitted. Climate scientists who promoted the climate “net-zero” policy—a simulated century-long carbon-offset model for aggregate atmospheric emissions—have since conceded in terror that possibilities for future climate repair are being perverted to a countereffect through this policy. There is a deliberate misreading of and inflated faith in climate restoration techniques, whether technological carbon removal or biological habitat rehabilitation, which shape the pathways of the net-zero model but are yet to be developed and deployed. As these future repairs are built in as assumptions within the model’s extended time horizons, in the present they are used to bolster and justify further fossil burning.8

Restored to what?

In 2021, the United Nations announced that we have entered the Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, declaring the need for dramatically scaled international efforts to restore a billion hectares of land and ocean (roughly the size of China). Yet, as a young and evolving science, increasingly also crowded with voices from the social and political sciences, restoration ecology is faced with the problem of defining what exactly the targets of restoration should be and why. Traditionally, restoration of a degraded or depleted ecosystem focused on re-establishing historical conditions to within a range of expected variability. Under this remit, aiming for fidelity to a specified historical baseline was envisaged to enable species and ecosystem communities to thrive and adapt to change and disturbance within the biophysical range in which they evolved. But with each record-breaking annual temperature, rainfall, drought, and migration of species and pathogens from one area of the globe to another—as dramatic presage to the anthropocenic condition—these historical baselines have mostly vanished. While a return to a prior state is implied in the term “restoration,” it is more likely that what is being restored is a certain level of function or integrity within an ecosystem’s key processes.9 Whether and how an ecosystem is restored, to what specified functionality, and for whom is therefore an intrinsically political concern of the Anthropocene, and most pronouncedly in light of the dynamics of green and blue capitalisms.

Infrastructural maintenance

Perhaps, in supposing that ecosystems are amenable to “repair” in the first place, we can never really escape notions of technical, substitutable, “infrastructural natures.” Repair invokes ideas of artifice and operational form; the “making work” of something fundamentally in service to its users. In this sense, novel ecosystems shaped through human hands and capitalist systems are increasingly being viewed explicitly as infrastructure, with the capacity to perform in equivalent if not superior or cheaper ways to the cemented, piped, and cabled “gray” kinds of infrastructure. “Green-blue infrastructure” is a framing for the ecological-material processing functions that generate “nature-based solutions” to the various environmental ills and socio-metabolic needs of modernity. Such ideas and schemes are becoming naturalized across the governance apparatus of many advanced industrialized nations. Their policy approaches make ecosystems “legible, governable and investable” specifically “to mobilise the regenerative power of biotic life to invigorate the liberal promise of infrastructure.”10

Talk of green and blue infrastructure makes it startingly apparent that the politics of “who decides what” emerges through a reparative mode of production. Repair for critical infrastructural and technology systems requires what has been spoken of as “articulation”11 to make the repair and maintenance work fit into or onto the existing orders and value systems of whatever it is that is being modified, so as to prevent too great of a schism or disruption. With respect to the biopolitics of environmental governance, I suggest it is exactly here that repair comes undone. In the act of “making fit,” repair that is formed in and around existing political and economic structures is little more than maintenance for a technocratic and liberal incumbency controlling the terms of articulation. Repairing infrastructural natures, or even maintaining them, for functional performance is distinct to building integrated systems of abundant, autonomous, un-certain, and un-optimized becomings—flourishing ecologies instead of renewed sites for extraction.12 That is not to say that such ecologies need necessarily be pristine, wild, or premodern, but rather that it matters by which values and for whom ecosystems are (re)produced and why. Indeed, the production of ecosystems—even economically useful ones that provide all kinds of human and interspecies sustenance—has always been the outcome of collaborative co-productions between the labors of human hands and nonhuman paws, beaks, hooves, mandibles, proboscises, membranes, and jaws. We have all always been “ecosystem engineers,” though some of us claim more “world making and breaking” capacities than others.13

Resilience for more of the same

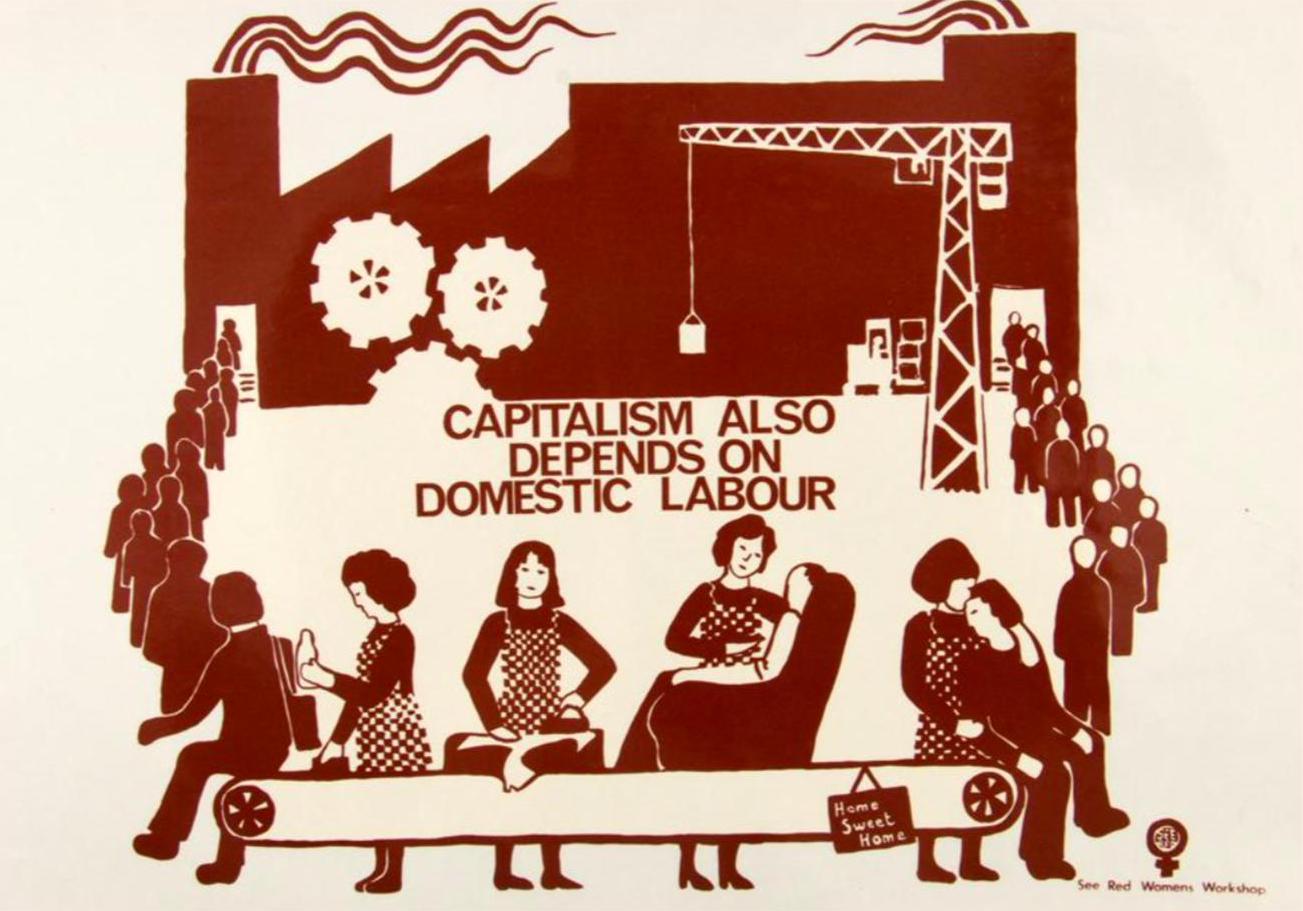

In exploring the reparative mode of production that seeks to secure, through capitalist logics, the regenerative capacity of biotic relations as “the work of nature,” we might also remember the Marxist-feminist appeals for society to recognize “women’s work.” This movement define this work as the unvalued but critical reproductive and emotional labor supporting, repairing, and regenerating workers’ bodies and minds.14 Reproductive labor, in renewing capacity for generative perpetuation, while not equivalent, could resemble the autopoiesis of a functioning ecosystem that “produces itself by producing the very elements that compose it as a system”15 or the immunitary mechanisms of a healthy, healing organism.16 To shift ideas of immunity—given its constitutive role within restorative, reparative, reproductive processes of both human bodies and the work of nature—to the center stage of repair is to be able to think about a kind of work (and care) that is premised on repairing the repair mechanisms themselves.

Activities and relationships of care for social and bodily reproduction makes visible repair as an intrinsic and constitutive factor of value production through supporting rest, renewal and resuscitation. “Capitalism also depends on domestic labour” from the book: See Red Women's Workshop: Feminist Posters 1974-1990. See Red Woman’s Workshops was a feminist a collective screen-printing studio operating in London between 1974-1990. Image by See Red Women's Workshop, CC-BY-ND-SA 3.0

For living systems to be able to “bounce back,” heal, and repair after infection or injury—to be able to generally reorganize in response to dynamic change—animates hopes for interventions to cultivate socio-ecological resilience, defined broadly as the ability to recover following stress or disturbance.17 Resilience theory in ecology replaces outdated models of ecosystem “stability” and equilibrium states that would require controlled management to prevent disruptive impacts. The notion of stability, therefore, appears to be aligned to the onto-epistemological milieu of the Anthropocene. But while, by contrast, resilience thinking seems to embrace the dynamic and nonlinear entanglements between humans and nature, it is—much like the broader story of an incumbent capture of repair I have been telling here—becoming a strategy to merely uphold the modernist-liberal traditions that have led us into the Anthropocene. Insofar as resilience has “the effect of tethering innovation and imagination to the maintenance of existing economic, social and political relations,” it functions not to change anything about how we live but instead to powerfully “ward other ways of living off.”18 Resilience is heralded as a savior governance strategy, one that increases adaptive capacities to change and maintain system identities and functions, so as to ultimately keep all other things the same.

Repair as a becoming ready for the “not yet”

The diagnosis of the Anthropocene is one of breakdown of the repair mechanisms of Earth systems. Biogeochemical regulatory functions have switched so that vital constitutive forces made from lively milieus of human and nonhuman labors have eroded to the point of being defunct. What will emerge in their absences is uncertain. Thresholds in the regulatory functions of Earth (at least within the time frames relevant to us and innumerable other species) have been breached, setting off pathways of irrevocably and dynamically altered conditions. For all the disorientation, bewilderment, risk, and uncertainty the Anthropocene presents, it does insist that we reconcile with the idea that there is no way back to past states. But what can we make of repair if there is no way back—only onward toward future functional forms? The question we face is not necessarily whether and to what extent the Anthropocene condition is reparable; rather, we must ask what kinds of functions, futures, and worlds we want to participate in making and who gets to decide on and partake in these processes.

I have found it helpful to think about where the word “repair” comes from in trying to imagine a better term. It derives from Latin “parare,” meaning to “make ready or produce.” A reading of the word “repair” in this light—through its orientation to something else, its commitment to the present moment, and its reckoning with what has come to pass—stands in contrast to the idea of repair as a return. Commitments to “being ready,” rather than going back, therefore imply alterity—maybe even transformation. This kind of repair is arguably about further breakage rather than patch-ups. It is for endings, retirement, and palliative treatment—building hospices for catastrophe-generating modernity.19 A reparative politics might also be one of refusal to participate in a system that denied anything was ever broken in the first place.20 The progress machine of liberal humanism, which has been declared a failure by the delimitation of a condition called the Anthropocene, has always been profoundly dysfunctional for the majority of Earthly populations. Perhaps it is only in accepting what is broken and exploring what else is possible that we can consider an “aftermath” to “fill in the moment of hope and fear in which bridges from old worlds to new worlds” can be built.21 Cultivating our capacities for more and better “broken-world thinking” is useful for this purpose.22 “Fixing” repair from this perspective might then become generative and productive for social institutions, politics, and economic relations that far exceed sector-specific forms of restoration, recognizing the essential factors of regeneration, not so they can be captured but so that they can be nurtured, cared for, and supported.

As well as endings, repair is therefore resolutely about the “not yet.” Here, repair becomes more akin to supporting enabling conditions for collective and cooperative interventions toward autonomous and ultimately uncertain and pluralistic becomings. But this still demands honesty and acceptance—not avoidance—over the scale, risk, and complexity of coordinating action that must be democratic and commensurate with the gravity and scope of the situation at hand. Technical expertise, advanced innovation, and industrial technologies will no doubt be required, along with situated and distributed efforts at the grassroots level—and the politics of participation in both spaces remains crucial.23 It is problematic that a reparative model of production is being constructed by blinkered technocrats and shaped by the interests of capital, thus experimentations in deliberative, collective alterity beckon. Those already underway can be better illuminated. These are experimentations not just in practice- and institution-building but also in critical thinking, ways of seeing, and modes of framing and supporting the co-productive processes of a living oikos. Repair is broken, if not dead. But before we rush to fix it, we would do well to remember there is nothing to return to—only uncertain possibilities worth struggling for. For those engaged in reparative work, recuperative logics, ethics and priorities might instead be grounded in preparing and becoming ready for what is emerging through and as the Anthropocene.