Re-patterning with Kudzu: Reckoning in Search of Regeneration

The kudzu plant—a climbing vine notorious for its rapid growth—has a long history of co-evolution with humans, having been both championed and vilified since arriving in the Americas from East Asia in the nineteenth century. This rollercoaster of American engagement with kudzu makes it an apt focal point for approaching questions around nativeness and belonging, human exceptionalism, multispecies solidarity, and ecocide. In this essay, interweaving text with photography and film, artist Ellie Irons documents her travels to Natchez, Mississippi, to meet kudzu. With the guidance of plants both native and migrant, Irons finds space to re-pattern herself as a cohabitant and collaborator in ecosystem regeneration.

Meeting Kudzu, Palm to Leaf

A trickle of sweat slips down my spine as I step into the deep shadow of a towering bald cypress tree at the edge of a shallow pond. Spanish moss hangs still in the midday sun, and lily pads float on dark, still water. Blinking as my eyes adjust to the contrast, I peer across a large, closely mowed field ringed by a grove of neatly trimmed old oaks. Though the rising heat I can just make out the roof of the Greek Revival mansion that is the centerpiece of the Natchez National Historical Park in Mississippi. Two hundred years ago, the manicured landscape unfolding before me was covered in cotton plants. As I rest in the shade, I sense their ghostly roots spreading through the soil below my feet. I imagine those roots sucking up nutrients laid down over millennia by the meandering river Mississippi River, bringing silt from a watershed half a continent wide. I envision how those nutrients were embedded into plant tissue, which then produced leaves, buds, blossoms, and finally, gossamer puffs of cotton. I strain to comprehend the exhaustion of life and land as, season after season, enslaved people harvested that cotton, stripping nutrients away in the form of the “white gold,” the main cash crop for the plantation system in this region. The venerable southern live oaks I can see in the distance may understand. Long-lived beings, some of these trees likely survived the plantation era. Their direct ancestors may have lived alongside the Indigenous Natchez people whose homelands these were prior to European invasion and colonization.

Since this land became a park in the 1990s, many tourists have stood where I stand now. They have framed the landscape before me with cameras, generating photographic souvenirs of a seemingly bucolic view. But this is not the view I came here to see. Having regained my resolve beneath the bald cypresses, I rotate my body so that my back is to the pond and the Melrose mansion. Now I face the busy street that marks the edge of the park, and beyond that street, I can make out a deep ravine covered in a verdant tangle of vegetation. On the other side of the ravine are the trim backyards of a suburban neighborhood. I wait for the traffic to ebb, then set out across the sunbaked asphalt toward the ravine. When I reach the other side of the street, I step onto soil that is barren and cracked. Looping vines twist out of the ravine, reaching across the bare soil toward the road. Stooping to examine them, I see circuitous stems covered in coarse hairs. These vines emerge from a mass of gently lobed leaves, in clusters of three, layered one atop another into a voluminous mass. Watching my footing on the steep slope, I take a tentative step into the vegetation. Stooping again, I lift a cluster of leaves and catch a glimpse of purple petals in the dappled light. I crouch lower, awkwardly maneuvering the blossom toward my face as I sink into the vegetation. I take a deep breath, pulling the petals to my nostrils. Unmistakable: the scent of sweet grape candy, or overripe concord grapes. Yes, this is kudzu (Pueraria montana), the plant I’ve come to Natchez to meet.

A Companion Plant for a Troubled and Troubling Age

When I was invited to engage with the land currently known as Natchez, Mississippi, through the lens of the Anthropocene, I knew it was time for me to contend with kudzu. Known colloquially as the “vine that ate the South,” this climbing vine has a long history of coevolution with humans. Since it arrived in the Americas from East Asia in the late nineteenth century, it has been variously championed and vilified, exploited and attacked. This rollercoaster of American engagement with the plant makes it an apt focal point for approaching questions around nativeness and belonging, human exceptionalism, multispecies solidarity, and ecocide. These questions are also central to my interest in joining other scholars and artists in interrogating the Anthropocene as a conceptual framework and geological age.1

Before starting this project, I had never encountered a living, breathing kudzu plant at close range. As an artist who works closely with spontaneous urban plants (a.k.a. weeds), I engage regularly with vegetation that lives in close association with humans. As part of my ongoing Feral and Invasive Pigments (2012–) project, I give workshops on making watercolor paint from weedy, urban-growing plant species like pokeweed (Phytolacca Americana) and Asiatic dayflower (Commelina communis). Kudzu often comes up during these workshops. Participants are excited to tell me stories, often secondhand, about how the vine swamps houses, climbs in windows, and smothers cars and telephone poles. Thus, kudzu has long inhabited my psyche.

I traveled from my home in the Northeastern United States to the banks of the Mississippi, to the land we now call Natchez, to meet American kudzu on the contested terrain it has colonized alongside many other migrants. As a settler on Turtle Island, I wanted to ground myself alongside kudzu, to contemplate our shared complicity in the ecocidal system that has brought us together. While far too brief, my five days of fieldwork in Natchez provided me with an opportunity for bodily engagement with this infamous being. Through strategies expanded upon below—including public fieldwork, a kudzu-entanglement workshop, and a video and audio guide—I sought entry points to explore a tenacious set of ills that plague the Western, settler-colonial environmental imaginary under late capitalism. These engagements with kudzu, which I frame as opportunities for re-patterning that imaginary, are buttressed by textual and archival research that interrogates forms of environmentalism that are premised on purity and exclusion, from herbicide-based restoration to white nationalist ecofascism. In the hybrid video and text essay I present here, I relate what I learned about kudzu, both its naturalcultural history and ongoing life in the United States, and what I gleaned of its lived reality on the ground in Natchez.

During my time in Natchez, kudzu helped me flip my focus. Whether visiting a monument or a historical site—or just a grocery store or a gas station—seeking out kudzu lent me an inverted view of the city. The negative space between “points of interest,” and mundane urban infrastructure came into focus, revealing an alternative topography dotted with its own arresting focal points: a series of what I came to describe as kudzu inversions and kudzu obelisks. Rooting in hard-to-maintain interstitial spaces and overlooked gaps in the urban landscape, kudzu thrived in gullies, ravines and depressions, creating inversions; it climbed vertical infrastructure like billboards, telephone poles, and lamp posts, creating obelisks. From this realization a typology of three forms emerged to guide me through my research in Natchez. Obelisks and inversions became focal points, from which vines sprawled outwards until they came up against a street, sidewalk, lawn, or other impediment. It was here, along the edges, formed between kudzu and the rest of the city, that I did much of my fieldwork.

A selection of forms from the Obelisk/Inversion/Edge Typology that emerged during fieldwork in Natchez. Natchez, Mississippi, September 2019. Image courtesy of Ellie Irons

Bringing my artistic practice to the heavily layered landscape of this riverside habitat through the lens of kudzu was both challenging and clarifying. While text-based research—ranging from nineteenth-century newspapers to contemporary ecology studies—is essential to what I present here, the core of the project revolved around direct interaction with kudzu in Natchez through an approach I call “public fieldwork.” This artistic research strategy draws on and combines aspects of socially engaged art, feminist performance art, multispecies studies, traditional and local ecological knowledge, and community science, among others. It involves carrying out my artistic practice outside, in public view, as a means of interacting with and drawing connections among a diverse, multispecies audience. Ongoing, in-depth work with a core group of collaborators—including both plants and people—continues to help me refine this methodology, which responds to our protracted environmental crisis by cultivating multispecies solidarity in urban and disturbed ecosystems.

Key collaborators and interlocutors in the development of this methodology include the spontaneous urban plants of Brooklyn, New York, and the members of two collaborative groups I work with, the Environmental Performance Agency and the Next Epoch Seed Library. We advocate for multispecies solidarity by imagining and enacting forms of sociality between humans and weedy plants. Alongside many others, we seek to contribute to the break down of damaging, relatively recent, and predominately Western binaries between humans and the rest of nature. As a white, settler artist seeking to learn from and with plants on the lands currently known as the United States, I have the responsibility do so in deference to and in solidarity with the long history and ongoing present of Indigenous peoples who know plants as kin.2 While beyond the immediate scope of this project and essay, the work of repatterning deeply seated tendencies to separate so-called “nature” and “culture”—held both in my own body and in dominant societal structures—must also involve active work in support of Indigenous resurgence across this continent.3

Kudzu and the landscapes it inhabits are particularly rich and troubling terrain upon which to attempt these re-patterning interventions. As Maya Kóvskaya, curator of Field Station 5: Place, Space, and Relations of Belonging, observes in her writing about Natchez as a site of exploration: kudzu “shows the complex and consequential entanglement of the twin concepts of white supremacism and human exceptionalism and their intertwined instantiations in genocide and ecocide, giving form and motivational force to the emergent Anthropocene conditions along the Mississippi since the start of the colonial era.”4 As Kóvskaya describes, the role of soil erosion and kudzu inhabitation provide me with the specific, grounded lens through which to engage the “widespread colonial processes and outcomes” that are mirrored in the Natchez context.5 Throughout my time in Natchez, a landscape straining under the legacy of plantation monocultures, chattel slavery, and Indigenous genocide and contending with the contemporary realities of racial segregation, poverty, and extractive industries, I was haunted by a series of pressing questions.6 What does an anti-racist, nonviolent restoration ecology look like in the face of mass migration? How can we actively counter “Make America Green Again” scenarios that harken back to a fallacy of pristine wilderness premised on Indigenous erasure? Who benefits and who suffers under schemes to “eradicate” nonhuman life forms labeled as invasive? And what impact does this rhetoric have on white settler-colonial attitudes toward the rights of human migrants? Kudzu, a misunderstood edge dweller in an Anthropocene drama, could not answer these questions for me. But it proved to be a compelling companion with whom to contemplate them. Alongside kudzu, I sought opportunities to re-pattern myself, seeking the narratives of abundance, regeneration, and flux that are so necessary if we are to replace the tired and dangerous habit of telling tales premised on scarcity, rigidity, and fear.

From Exotic Miracle Plant to Alien Invader: Kudzu in the Sights of Invasion Biology

There is much to explore in kudzu’s history in the United States, from its introduction as novel horticultural species in the Gilded Age—which also coincided with the Jim Crow era in the South—to its championing as a soil-building miracle plant during the Great Depression. We’ll return to the conditions that generated several decades of kudzu-mania shortly. But as befits the plant known notoriously as the “vine that ate the South,” we’ll begin with kudzu’s fall from grace. After being planted in the millions and celebrated for its rapid growth as late as the 1940s, by the 1950s, as it naturalized to its new home, kudzu was recognized as too successful. It was taken off the US government’s federal list of recommended plants for soil stabilization and recovery in 1961.7By 1970, it was identified both by ecologists and the state as a weed, and by the 1980s listed by many states and municipalities as a specific kind of weed: an invasive species. By 1997, it was finally listed as a “noxious weed” at the federal level.8 Each of these designations raised the stakes for the plant’s containment and eradication. Over the last half century, kudzu has become notorious in the public imagination as well. Images of the plant overcoming infrastructure, from houses to telephone poles, are widespread, and the species has become an icon for illustrating the dangers of introduced plant species.

While the term “weed,” used to refer to unwanted or undesirable forms of vegetation, has been part of the English language for at least a millennium, “invasive” as applied to plant life has more recent origins.9 The term was originally defined by zoologist Charles Elton in his 1958 book on the topic, in which he describes a “biological invasion” as “the enormous increase in numbers of some kind of living organism” often due to introduction to a novel environment.10 Writing in the wake of the Second World War, Elton employed militaristic terminology, likening the arrival of new species to a “bombardment,” with “ecological explosions” akin to nuclear bombs.11 Now known as “invasion biology,” the field he helped found has grown exponentially since the 1950s, and the term “invasive” is used in many contexts, from municipal codes to dinner menus.12 Like any term used across disciplines and contexts, its meaning is slippery. While colloquially the term is often used to describe anything not considered native to a region—“native” being a questionable designation in its own right—at the federal level in the United States “invasive species” are defined as those “whose introduction causes or is likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human health.”13

Examples of how violent and militaristic imagery is used in some campaigns promoting the management of introduced and invasive plants. The logos here are drawn from various state and municipal programs around the United States. Image courtesy of Ellie Irons

After entering the scientific lexicon in the 1950s, the concept of “species invasion” took several decades to seed in the public imagination. As it entered the public discourse, it carried with it the violent rhetoric of the field’s founding. The excesses of the 1980s, as Americans recoiled from the radicalism of the 1960s and ’70s, set the stage for the first widely circulated eradication campaigns aimed at unwelcome plant migrants.14 This is also the decade that saw President Ronald Regan sign into the law the Immigration Control and Reform Act and climate scientist James Hansen alert the United States Congress and the American public to the dangers of global warming. Concurrently, the Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment defined an international approach to combating so-called invasive alien species and brought invasion biology into a new phase of power and influence.15 These sociocultural moments are not unrelated. As biologist turned feminist science and technology studies scholar Banu Subramaniam describes: “The narrow lenses of the biological sciences see invasive species purely as a biological problem, and the narrow lenses of the humanities see xenophobia or racism as a human problem. […] There are deep links between the nationalization of nature and the naturalization of nation.”16 Subramaniam suggests there are connections between a distinctly American form of environmentalism—premised on manifest destiny and the containment, regulation, and conservation of a “pristine” wilderness landscape—and strains of protectionism, nativism, and nationalism that have animated American culture in waves since the country’s founding.17 The urge to protect and conserve, even when catalyzed by well-meaning attempts to “save the Earth” from the perils of a changing climate, can overlap with and feed into ideologies based in xenophobia and genetic purity, as seen in populist and fascist movements from New Zealand to England to the United States.18

While horrific acts of violence linked to ethnonationalist ecofascism have punctuated the news in recent years, the roots of ecofascist tendencies in the United States and other Western societies are deep. Reflecting on links between contemporary ecofascism and its progenitors, scholar of transatlantic English literature Jessica Krzeminski traces how “an emphasis on purity disguised as a return to morality” has informed settler attitudes toward human newcomers since early in the history of the American nation-state.19 Krzeminski finds examples of ecofascist attitudes in the United States as early as 1880, as the post–Civil War Reconstruction era came to a close and immigration from Eastern Europe expanded rapidly.20 Known as the Gilded Age, this is the time period in which social Darwinist ideas reached the United States and were translated into racist and classist social policies based on eugenics, from immigration reform to forced sterilization.21 Environmental policy researcher Anna Eskridge and cultural geographer Derek Alderman explore these undercurrents in their analysis of the fate of kudzu a century later. Writing about attitudes toward kudzu in the late twentieth century, they describe the species as an “environmental ‘other,’” around which “discourses of fear” reverberate, creating the conditions for anti-kudzu legislation at the state level.22 In their analysis, it is these fear-based narratives, exemplified by labeling kudzu a “plant thug” and “alien invader,” that did more to drive this legislation that any material evidence of the plant’s biological tendencies or ecological effects. Parallels to the contemporary anti-immigration climate in the United States are undeniable.23

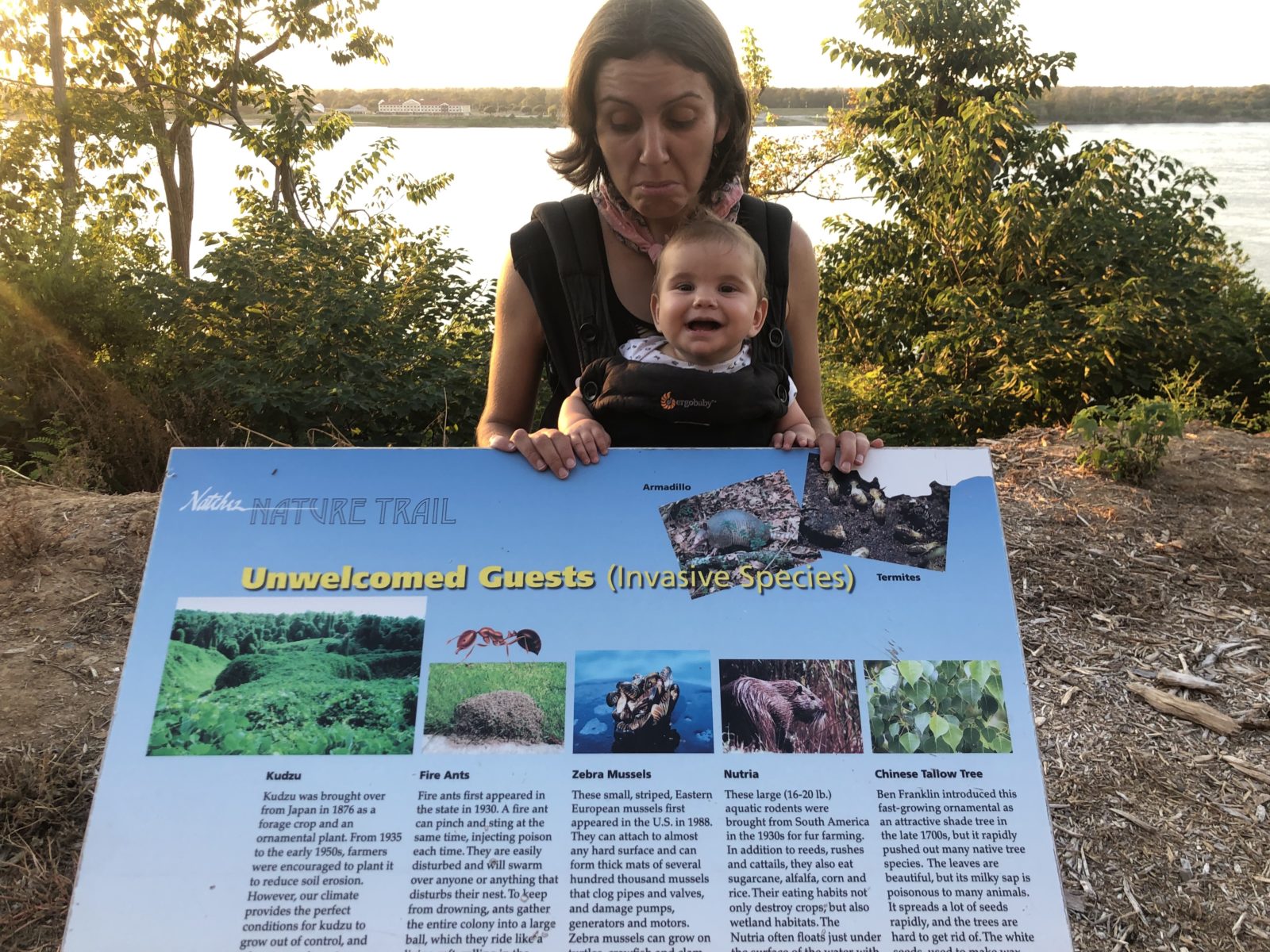

The author and her daughter examining a sign found along the Natchez Nature Walk, which reads, “Unwelcome Guests: Alien Invaders.” Along the length of this city-maintained path, trees, vines, and herbaceous plants have been cut and mowed, allowing for a view of the Mississippi River but resulting in dry, cracked, exposed soil and little shade. Natchez, MS, September 26, 2019. Photo credit Dan Phiffer

To return to the data, which is so easily masked by fear-based rhetoric, while the drivers of extinction are complex and multifaceted, again and again studies and reports show that human-driven habitat destruction has been—and will continue to be—the top cause of biodiversity decline.24 Depending on how the data are crunched, species invasions do play a role, but in specific ways that are context-responsive and entangled with the impacts of habitat destruction.25 In many cases, so-called invasive species flourish as the passengers rather than drivers of ecological degradation.26 In other cases, introduced species naturalize and don’t reduce—or may even support—native species diversity.27 Additionally, “solutions” for stemming the spread of migrating species are often expensive, ineffective, and even at times destructive.28 Even so, an obsession with eradicating so-called invaders persists among conservation-minded Americans.29 Promoted through campaigns that often other and vilify the species in question, the effort claims the attention and energy of conservation biologists, agrochemical engineers, and weekend “weed warriors” across the United States.30 I will explore possible drivers of this ongoing vitriol in a later section, but first we will examine how kudzu was received when it made its debut on the North American continent.

Welcoming Kudzu in the Gilded Age

While today Americans know kudzu as an infamous invasive species, it wasn’t always so. When it was introduced in the late nineteenth century, kudzu was initially welcomed as a luxurious novelty by a settler-colonial culture still in the process of world-building. Arriving in the Americas in the wake of the US Civil War and the closing of the frontier, kudzu made landfall on earth seeped in bloody struggle, racial violence, and Indigenous genocide. As scholars of the American perception of landscape and wilderness have explored, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, settlers were reimagining and remaking land taken in violent conquest, and searching for an American identity amid ongoing turmoil.31

Among the tactics for settling and pacifying the new American “wilderness” was the purposeful introduction of familiar European species and the importation of novel species prospected from colonized regions around the world. Long known in East Asia as a medicinal, forage, and food crop, kudzu was presented at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876 as part of the Japanese Pavilion, where it was appreciated for its ornamental qualities and intensely scented purple blossoms.32 Some sources report that the plants were destroyed after the fair—whether they were perceived as a threat, or just as disposable, is unclear. Regardless, it seems kudzu did not naturalize after this initial introduction, likely because it was maladapted to cold northern winters.33 It is widely reported that kudzu was presented again at another world expo, in New Orleans in the 1880s, most likely at the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition of 1884.34

Thus kudzu arrived in the United States just as the American Gilded Age was germinating. This was the period of industrialization, expanding railroad networks, and international trade that made northern robber barons rich at the expense of a largely immigrant working class. As social Darwinism and the eugenicist policies that would flow from it began to take hold, other forms of ecosocial engineering were afoot. In this same decade, the American Acclimatization Society was founded to introduce to the North American continent familiar European species “which were useful to the farmer and contributed to the beauty of the groves and fields.”35 This enthusiasm for augmenting or even replacing species indigenous to the Americas with species perceived as more beautiful, useful, or familiar continued unabated through the mid-twentieth century, even as early conservation and preservation movements began to advocate for the value of so-called pristine wilderness habitats populated by native species.36

In line with this enthusiasm for introduced species, by the late nineteenth century kudzu seeds and seedlings were available for sale in mail order catalogs. Enthusiasts promoted the species as nutritious fodder for livestock, but its spread was gradual. Farmers found the plants slow to root and hard to harvest as an agricultural crop compared to cash crops like cotton and tobacco.37 Until the 1930s, the plant remained a horticultural novelty without solid footing in its new home. While kudzu foundered in the fields, it found sanctuary on the grounds of Southern plantation homes as a decorative veranda plant, where long summers, mild winters, and human companions eager to see it succeed kept it alive.

Kudzu’s Surface Level Success: A Veneer over Disturbed Habitats

While thousands of plant species have been intentionally introduced repeatedly since the advent of European colonization, most have failed to naturalize. Only a small fraction of intentional plant introductions, roughly 1,500 by some estimates, have resulted in new populations that can survive outside of greenhouses, gardens, and other carefully controlled environments.38 The vast majority of species that have naturalized, like kudzu, have found footholds in landscapes prepared for them by settler-colonial world-building activities.39 Species like dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), white clover (Trifolium repens), and broadleaf plantain (Plantago major), appreciated for their medicinal and forage qualities, now thrive in lawns across the United States.40 They are preadapted to this setting, where the blades of the mower mimic the mouths of grazing animals. Disturbance-oriented pioneer species like redroot pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus) take to the bare, sanitized soil of industrial agriculture settings, growing alongside cash crops like soybean and corn. Climbing vines like Asiatic bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), porcelain berry (Ampelopsis glandulosa), and kudzu take hold and persist in degraded soil in edge habitats created by deforestation.41 In each of these situations, settler-colonial world-building lays the groundwork for these so-called plant invasions, which unfold as co-created and collaborative events that cross species boundaries, involving both human and plant agency and ingenuity.

In the case of kudzu, the species has a suite of traits—the ability to grow rapidly on bare soil, reproduce vegetatively, and fix nitrogen—that rendered it well suited to two niches that were abundantly available in the first half of the twentieth century. These niches included worn-out agricultural soil depleted by centuries of monoculture cultivation of cotton, tobacco, and other cash crops, and freshly disturbed soil laid bare by the surge of infrastructure construction that took place in the wake of the Great Depression under New Deal programs like the Public Works Administration.42 Through this tumultuous period, as large portions of the Black population migrated out of the South fleeing drought, poverty, and Jim Crow–era oppression and violence, kudzu began to spread in their wake. It did so with massive amounts of help from the state and enthusiastic evangelists who embraced it as a kind of miracle plant to be put to work laboring for the cause of repairing and expanding American dominance as the still nascent nation was finding its footing on the world stage.43 The state subsidized the planting of at least 85 million kudzu seedlings throughout the south, and kudzu proponents further aided the cause, forming the Kudzu Club of America, which at its peak in 1943 was 20,000 strong.44

During this time, kudzu was planted not just on worn-out agricultural soil but also on road and highway embankments as national highway infrastructure expanded under the Public Works Administration in the 1940s and the Federal-Aid Highway Act in the 1950s.45 As miles and miles of new asphalt were laid down, they were lined with miles and miles of young kudzu seedlings. While many of the new plantings subsidized on agricultural land languished and disappeared—they were easily foraged away by livestock and plowed under by farmers ready to try another cash crop as markets recovered—kudzu found the edges of highways to be suitable habitat. It soaked up the ample light where forests had been ripped down and gashes cut in the soil to create ideal driving conditions. It climbed with pioneer trees as they grew from bare soil, just as it had climbed verandas in the century before. Here kudzu found temporary sanctuary on the edges of a car-culture infrastructure—on steep highway embankments, it was hard to reach with mowers and other maintenance machines. Once it had done its job of stabilizing raw embankments, the kudzu stayed on, temporarily unmolested.46 It blossomed and stretched and thrived, performing the miracle of growth for a new generation of Americans who traveled the country’s highway system by car. Framed by the car window, it now became the “vine that ate the South,” a mythical abstraction few have experienced intimately.

Destructive Surfaces: Asphalt, Turfgrass … Kudzu?

While ecologists and the state began to turn on kudzu in the 1950s, it wasn’t until the 1980s that kudzu became more widely known as a problem plant. Aided by publicity campaigns, media attention, and in some cases direct recruitment from those working in the field of invasion biology, a subset of the American populace became proponents of kudzu eradication campaigns.47 As many scholars and researchers have noted, during this time we can also observe the rise of a specific lexicon around introduced weedy species that parallels much of the language used to vilify and malign human immigrant populations.48 While language aimed at human immigrants often seeks to dehumanize them—they are “animals” and come as a menacing “high tide”—migrating plants are more commonly anthropomorphized as “barbarian hordes” who are “WANTED dead or alive” for “ecological crimes,” including “terrorizing natives” and “stealing land.”49 The categories of the vegetal and the human, so preciously separate in the hierarchy of Western human supremacy, here collapse into one and other, pressed into a hostile zone built on fear and myth, abstraction, and hate.50

Examples of materials from state and municipal invasive species management campaigns in the United States, taking the popular form of the “wanted poster.” This format is also offered as a class project for elementary school students on several platforms for digital lesson planning. Left to right: Introduced Pests Outreach Project poster, Massachusetts; Environmental Services Division outreach poster, Springfield, OR; Riverlink Poster, Asheville, NC; Invasive Species Project lesson plan, teacherspayteachers.com. Image courtesy of Ellie Irons

While much of the frenzied rhetoric around kudzu has an air of certainty, the plant’s physical roothold on American soil is actually tenuous and not well understood. Several recent articles on kudzu’s geographical footprint in the United States suggest that the plant is actually much less widespread and slower growing than the legends (and the weed warriors) would have us believe—its numbers may even be in decline.51 While conservative accounts of the plant’s range have reported that kudzu covers more than 2 million acres (with less conservative reports coming in at 7 to 9 million acres), recent studies, taking advantage of more accurate and efficient mapping technologies, suggest the plant may cover only 226,000 acres of land.52 Whether this is due to declining coverage or more accurate estimates is unclear.

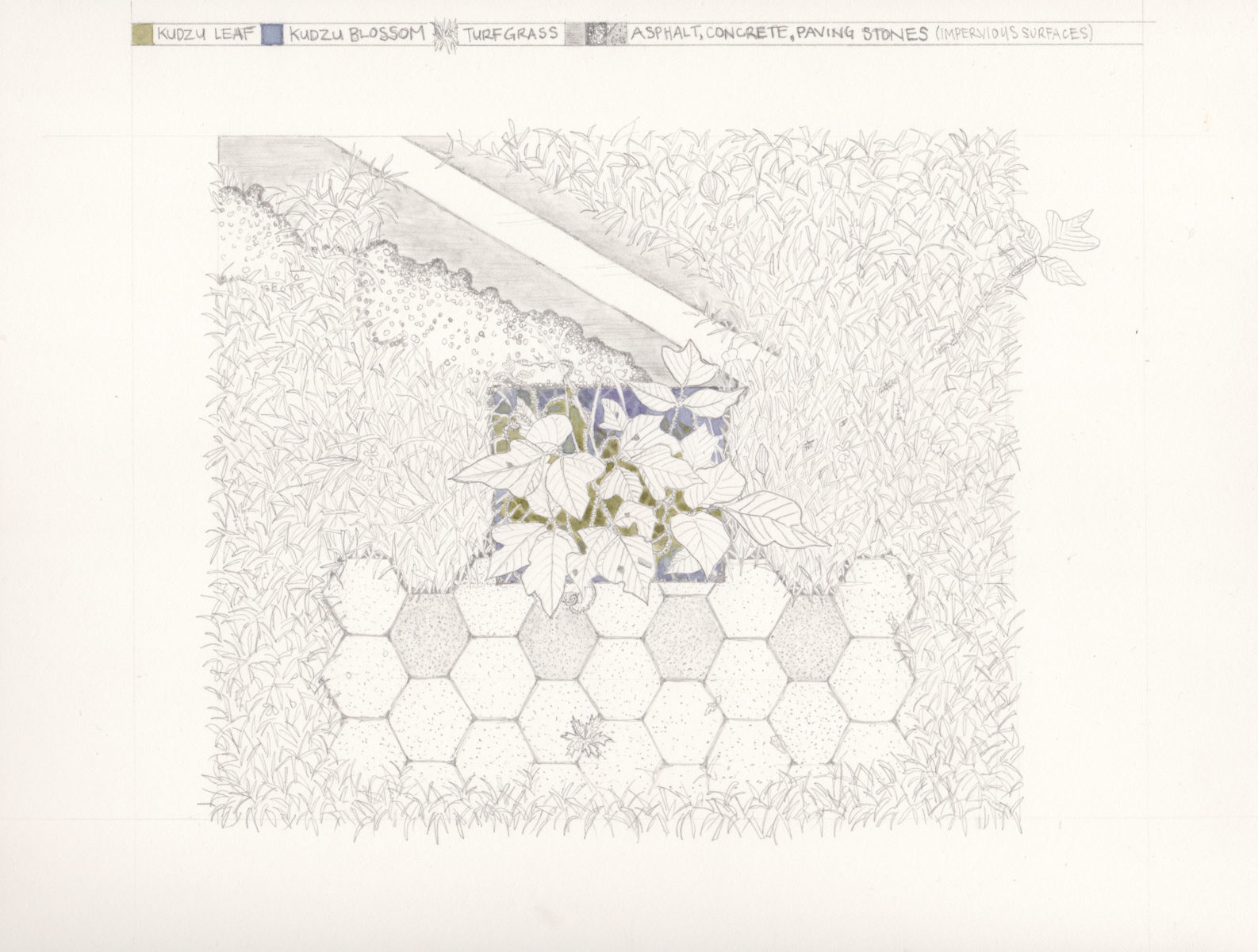

Even assuming the larger estimate of 2 million acres of kudzu on American soil, this figure is dwarfed by other ecologically devastating ground coverings that increase yearly with rampant development, contributing to habitat loss and accelerating climate change. Impervious surfaces, including streets, sidewalks, and buildings, cover roughly 27 million acres, or 1.13 percent of land in the continental United States, while turfgrass comes in at 40 million acres, or 1.9 percent.53 Assuming kudzu covers 2 million acres—again, recent estimates show it’s much less—that figure comes in at 0.082 percent of land in the continental United States. Largely this is disturbed land alongside highways, sandwiched between developments, and in fragmented forest patches. So why does kudzu play such an outsized role in narratives of ecological degradation? And why are these narratives so grounded in fear and hate? One simple explanation is that kudzu and other highly visible introduced plants provide an easy target. They live alongside us, integrated into our urban and suburban habitats. They present themselves to us by cropping up along the edges and borders, where they are relatively accessible and vulnerable to destruction at the hands of humans. Ripping them up, spraying them with herbicide, tossing them in the trash bin, or refashioning them as a consumer product has an immediate, visceral effect.

“Invasive” Ground Cover of the Contiguous US, 2019, a drawing from the author’s Invasive and Feral Pigments series, created with pencil and kudzu blossom paint made during an open studio event and workshop at Natchez National Historical Park, Mississippi. Image courtesy of Ellie Irons.

Attacking the turfgrass, highways, and sprawling developments that are the driving force behind the decline and extinction of many native species requires attacking the American way of life. Degrowth and economic restructuring for greater equity and sustainability requires long-term commitment to a complex process without a clear roadmap. Redirecting anger, fear, and a sense of environmental impotence toward othering and eradicating kudzu is less risky and more straightforward. Thus to this day, teams of dedicated “kudzu warriors,” earnestly tout the virtues of kudzu eradication.54

Adding Poison to a Climate Catastrophe

While some of the most visible anti-kudzu activity takes the form of community weed pulls that rely on volunteer labor, control strategies based on widespread herbicide application are also common and widespread.55 Though more than half a century has passed since biologist Rachel Carson’s potent 1962 treatise on the dangers of widespread pesticide use, and we continue to learn about the dangers of herbicide and pesticide application, biological control through chemical means remains a staple in restoration ecology to this day.56 In the decade leading up to kudzu’s designation as a federally regulated noxious weed in 1997, detailed plans for the species’ “containment and eradication” were developed, a phenomenon that has brought the plant into intimate contact with the agrochemical industry.57 Tensions continue to run high around banning or decreasing the use of herbicides like glyphosate, both in so-called pristine ecosystems and in areas heavily used by humans, like parks and other recreational spaces. Supporters of herbicide use insist that native species are being irreparably harmed by reductions or all out bans of herbicides, while others seeking to reduce or ban herbicide use debunk invasion biology and its reliance on chemical control as scientifically unsound. For example, in his book Invasion Biology: A Critique of a Pseudoscience, conservation biologist David Theodoropoulos writes, “Every time you hear the word invasive species—think Monsanto,” arguing that attempts to eradicate successful non-native species are promoted by chemical corporations intent on selling herbicides.58 In response to critiques like this one, take a recent opinion piece by veteran conservationist Ted Williams. He vehemently defends a herbicide-based approach, arguing that there is a “hysteria” around the connections between herbicide application and cancer in human populations. He insists that Monsanto’s glyphosate is “the safest herbicide ever used,” advocating for broadcasting the chemical across swathes of landscape in addition to more targeted point applications.59 These two viewpoints are a microcosm of the polarized approach to living alongside so-called invasive species in the contemporary American climate.

As authoritative voices clash in a rush to simplify and clarify, to answer once and for all how we should think and feel and act in response to so-called invasive species, the multifaceted life of kudzu in the Americas reminds me to hold space for complexity. While I find myself falling firmly on the anti-herbicide end of the spectrum—based on intertwined environmental justice and ecological concerns—I acknowledge that we are living in a moment rife with contradictions and wicked problems.60 Drawing on a feminist epistemology rooted in an appreciation of situated knowledge reminds me to be skeptical of narratives proffering neat, universal solutions to complex, localized issues.61 Both Theodoropoulos’ strident discrediting of invasion biology and Williams’ ardor for protecting native species with poison must be tempered with a context-based approach to staying with the trouble and holding contradictions together. Careful study and attention to the ecosystems and communities at stake is essential.62 Taking what I need from arguments like these, I turn to other guiding voices: those of Indigenous experts whose ancestors have long known plants as teachers and guides, and whose communities have been living through environmental collapse, and the dystopian future it portends, for centuries.63 Experts like environmental biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer and Anishinaabe botanical teacher Mary Siisip Geniusz, while not writing about kudzu specifically, provide plenty of examples for how to follow the lead of plants, weedy and otherwise, allying ourselves with vegetal life as we make our way through what has been, and will continue to be, a long, protracted climate emergency.64 Kudzu may seem an unlikely ally, but for someone like me with much to examine in my own privileged relationship to environmental collapse, it proves a solid companion.

When I wrap my arm in kudzu, or trace its border on the sky with my finger, I acknowledge that it is here on Turtle Island, doing what it does, because I am here. Because of me and people like me, species and lifeways that were present in precolonial Natchez have been lost. Kudzu and I are complicit in this disappearance. To engage kudzu is to engage the genocide of the Natchez people, the forced labor of enslaved Africans, and the monoculture cotton fields that debilitated the soil and prepared the way for kudzu to root. The struggle to eradicate this plant from the landscape through violence will never recreate what has been lost, nor will it validate or redeem the presence of settlers on this land. Pouring resources into kudzu eradication smacks of the kind of pursuit of purity through restoration that philosopher Alexis Shotwell critiques so well. As she describes in Against Purity: Living Ethically in Compromised Times:

[Purism is] one bad but common approach to devastation in all its forms. It is a common approach for anyone who attempts to meet and control a complex situation that is fundamentally outside our control. It is a bad approach because it shuts down precisely the field of activity that might allow us to take better collective action against the destruction of the world in all its strange, delightful, impure frolic. Purism is a de-collectivizing, de-mobilizing paradoxical politics of despair. The world deserves better.65

Documentation of a kudzu entanglement session facilitated by the author and Field Station 5 curator Maya Kóvskaya. After making watercolor paint from kudzu blossoms, participants touched, smelled, and intertwined themselves with kudzu. Several participants had never touched the plant or smelled its intensely sweet, grape-scented flowers, even though many of them had lived alongside it all their lives. Natchez, MS, September 29, 2019. Image courtesy of Ellie Irons

Applying this critique of purity to our ecosocial relationships to kudzu calls for a careful examination of the motivations behind kudzu eradication campaigns, and a case-by-case analysis of how individual kudzu communities are thriving or struggling across the Southeastern United States. Who is benefiting from their presence? Who is calling for their eradication? What resources and energies are sapped by this call that are desperately needed elsewhere? The kudzu inversions and obelisks I encountered throughout Natchez dot a landscape scarred by plantation monocultures and chattel slavery, the ravages of an agroindustrial past and petrochemical present, the ongoing stresses of a changing climate, and the deep inequities of the capitalist society that fuels it all. My time in Natchez, flipping my focus from houses, sidewalks, strip malls, and streets to the shrouds of green that fill the space between them, was generative. Kudzu roots in gullies and atop abandoned infrastructure, and it roils around the edges of lawns, parking lots, highways, and cemeteries. It marks an alternative geography in which to read the history and future potential of this land and the life it supports. Wading into this alternative geography and making close contact with kudzu literally shifted my perspective in a visceral way. Abstract concepts, language, facts, and figures about kudzu are entangled with the feel of delicate kudzu hairs brushing against my skin. This bodily knowledge is fuel for re-patterning myself and others like me to approach vegetal beings with the respect and reverence all life is owed.

In Closing: An Unexpected Sanctuary Where Monocultures Meet

On the third day of my public fieldwork in Natchez, I arrive early on the grounds of Regions Bank in downtown Natchez. Morning light slants across the neatly manicured grounds of the low-profile, single-story brick building, which is offset by a kudzu inversion surrounding it on three sides. I park in a recently resurfaced asphalt parking lot. As I step out of the car, I find the dark surface already radiating a warmth that portends the day’s oncoming heat. The parking lot is bordered with wood chips and a trim green lawn. The lawn, in turn, is encircled by a field of kudzu, which sprawls down a gentle slope and into a gully between a busy avenue and the back fences of a residential neighborhood, in an arrangement similar to the one I encountered opposite the Melrose mansion. As cars pull up to the bank’s drive-through ATM one after another, I spend the morning walking a series of transects between the parking lot, lawn, and kudzu field. I trace the sinuous border where lawn meets kudzu in slow, loping strides. I march from the parking lot, across the lawn, and deep into the kudzu field in a diagonal line from west to east. I sit on the border between each surface and observe the life forms around me, marking the outlines of kudzu against sky, lawn, and street with my fingertips.

I am particularly struck by what I see on the border where the kudzu field meets the lawn. The grass looks recently mowed, trimmed within a half-inch of the soil. I guess it has been treated with herbicide, since I see very few weedy interlopers in its expansive green surface. The kudzu field that encircles it is thick and uniform, about waist-high and more verdant than some of the older, deeper stands I’ve observed. It appears to have been cut back recently. Its border with the lawn is uniform and neat, but new vine tendrils are already creeping out across the shorn grass. All along the edge where these two monocultures meet, I encounter a vibrant array of plant and insect life I’ve observed nowhere else in Natchez. American trumpet vine (Campsis radicans) and scarlet creeper (Ipomoea hederifolia) twine among the kudzu, their vibrant, trumpet-shaped blossoms attracting hummingbirds. Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) and woodland lettuce (Lactuca floridana) stand tall, their yellow and lavender blossoms buzzing with bees and flies. Tucked into this thicket I find both Asiatic dayflower (Commelina communis), a plant I know well from making watercolor paint in Brooklyn, and its cousin, whitemouth dayflower (Commelina erecta). I also pause to watch a large garden spider perch on a kudzu leaf, and note clusters of kudzu bugs on the undersides of kudzu leaves, leaving lacy patterns as they munch at the foliage.

A sample of the plants collected during public fieldwork in the transition zone between kudzu field and lawn ranging from Asiatic dayflower (Commelina communis) to Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis), behind Regions Bank, South Canal Street, Natchez, Mississippi, September 29, 2019. Image courtesy of Ellie Irons

The richness of this zone of transition I encountered in Natchez makes me think of anthropologist Anna Tsing’s and feminist theorist Donna Haraway’s interest in contact zones. In conversation with one another and with the concept of the “edge effect” drawn from ecology, the two scholars contemplate the novel multispecies relationships that form on the boundaries between habitats.66 As Haraway, drawing on Tsing, writes in When Species Meet:

I remembered that contact zones called ecotones, with their edge effects, are where assemblages of biological species form outside their comfort zones. These interdigitating edges are the richest places to look for ecological, evolutionary, and historical diversity. […] Such contact zones are full of the complexities of different kinds of unequal power that do not always go in expected directions. […] Rethinking “domestication” that closely knots human beings with other organisms, including plants, animals, and microbes, Tsing asks, “What if we imagined a human nature that shifted historically together with varied webs of interspecies interdependence?” Tsing calls the webs of interdependence “unruly edges.”67

Haraway’s assertion that power relations do not always act as expected when species meet at edges resonates with what I observed where lawn met kudzu at Regions Bank. Monocultures created through human-plant interactions, both intentional (lawn) and unintentional (kudzu), met in an impure, imperfect, but functional refuge for species banished from other habitat types in Natchez. Along this edge I watched solitary bees move from kudzu to goldenrod to trumpet vine, visiting an assortment of blossoms that never would have been seen together in the nineteenth century, let alone in the era before European colonization.

While perhaps impoverished in the eyes of a conservationist, and anathema to the goals of a weed warrior, this small assemblage of biodiverse kudzu-lawn habitat is life giving to me, delivering a complex and fortifying brew of joy and sorrow. Acknowledging the vitality of a habitat like this one is, for me, a practice aligned with the capacious, regenerative, equity-oriented environmentalism of Shotwell, Kimmerer, and Subramaniam. The sorrow that accompanies this stance is unavoidable, for it involves acknowledging what has been lost. Grief becomes a constant companion in an era that requires, in Haraway’s oft-quoted words, “staying with the trouble.”68These diverse thinkers and doers draw on a variety of fields, from Western science to Indigenous agricultural practices, to approach the question of migrating plants and shifting ecosocial assemblages with a nuanced view. Rather than debunking invasion biology as a sham or embracing the war on weeds as the path to ecological salvation, they offer paths to move beyond these reductive choices. Alongside them, and with the essential guidance of plants both native and migrant, I find space to re-pattern myself as a better cohabitant and collaborator in ecosystem regeneration.