The Grid

I don’t see a contradiction between

institutionalization and creative capacity.

Félix Guattari1

There is a speed of subjugation

that is opposed to the coefficients of transversality.

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari2

La Borde Clinique holds an important place in the history of French psychiatry because of its primary role in what came to be known as the institutional psychotherapy movement. It was established in 1952 by Jean Oury, who was joined soon after by Félix Guattari.3 Oury considered that psychiatric institutions were ill and that it was necessary to treat them in order to treat the patients. This pathogenic effect of the environment was called “pathoplastic” (pathoplastique). Hence the famous expression: “To treat the ill without treating the hospital is madness!”

This meant considering the hospital in its social and political dimensions. A series of organizational protocols were set in place at La Borde with the primary goal of stimulating patients’ autonomy, allowing them to regain a sense of responsibility and “re-appropriate the meaning of their existence in an ethical and no longer technocratic perspective.”4 A new spatial dynamics was also implemented to prevent the reinforcement of power structures. To give a few examples, patients had the freedom to walk wherever they wished and the spaces associated with medical functions had to rotate. Equally, it was considered that medication should not be given always by the same person. With these measures the scope of analysis was no longer limited to the privacy of the consulting room but was extended to the whole of the institution. For Oury and Guattari, the fabric of La Borde’s daily-life dynamics was thought to offer analytic opportunities of diverse kinds. Out of this series of experimental organizational protocols developed at La Borde, one in particular merits our attention—“the grid”—as it exemplifies the emancipatory potential of institutional processes.

The protocol

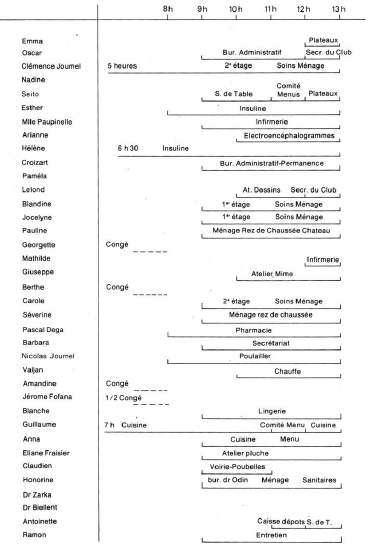

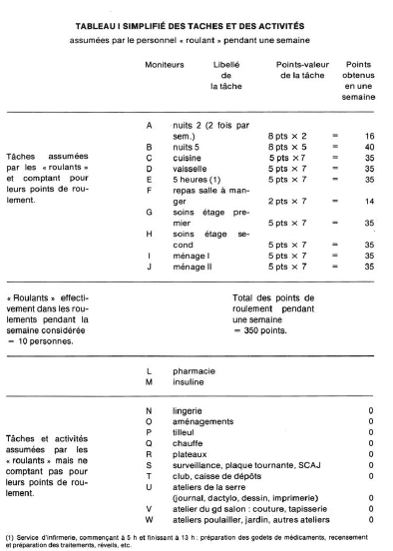

The grid was a rotational work schedule, divided by tasks and activities. It had the names of people rotating and the amount of time each person would spend on each task or activity per week. Visually it consisted of two axes—a vertical axis with a list of the names of the people in charge of specific tasks or activities and a horizontal axis to measure time, from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m. (Figure 1). Emerging around 1957, the grid arose from the need to “frame the deregulation”5 (Guattari’s words) while at the same time attempting to preserve the amicable atmosphere of the clinic (in its early years, La Borde was largely self-managed and spontaneously organized). A sample grid from the 1960s includes in the list of tasks dishwashing, housecleaning, kitchen and night shift duties, waiting at table, and many others. Activities were things such as the clubs, the journal, or the laundry. Tasks and activities were distributed according to their degree of agreeability.6 The tasks were associated with “disagreeability” and the activities with “agreeability.” Tasks ought to be shared by everyone given that they assured the minimal daily functioning of the clinic and thus were deemed everyone’s responsibility. For each task there were points relative to the value of the task and relative to the number of times a person performed that task (frequency). Points were accumulated and could be used to bargain when discussing the daily grid (Figure 2).

In this manner, the definition of tasks and activities worked as an indicator of what the majority of people inhabiting the institution deemed more or less pleasant. An example of this was the laundry, which several texts refer to as being one task that everyone wished to perform. From the perspective of institutional analysis, this apparently unimportant aspect could open a window into something else—something that would otherwise go unnoticed. As such, the grid allowed mutations of desire and subjective investments to be traced, insofar as these were expressed at the level of institutional dynamics. At the same time, as an organizational protocol it made power relations visible—in particular, all those aspects left outside the traditional doctor–patient relation. It also brought to the forefront relationships existing in the background: the institutional context, its constraints, organization, specific practices, and so on. Each institutional event, material or immaterial, discursive or non-discursive, was given expressive potential.7 In this view institutional analysis is fundamentally collective. This is not just because, in its strict meaning, analysis is no longer a privilege of the therapist only but is collectivized—i.e. it takes place collectively (in group sessions, discussion, etc.). But, in a more important sense, it is collective because it is impacted by spatial dispositions, linguistic and signifying dimensions, technical, economic, and sociological factors, rather than purely by personal, individual dispositions. Guattari’s conceptual elaboration of the grid gives an insight into what was at stake with such a simple protocol of organization and quantification. In the text “La ‘Grille’,” Guattari refers to the grid as an “articulatory system” whose goal was “rendering articulable the work’s organization with the subjective dimensions, so as to allow for certain things to come into the daylight, to allow certain surfaces of inscription to exist.”8 Take as an example the composition of the team managing the grid (the grilleuses). This team, itself rotating, was not to be composed of doctors so as to prevent the division of labor and daily structuring of the clinic to be congealed around the same medical structure. The measure did not aim to deny medical expertise but to impose limits on the organization of work coming from one single source: in other words, to allow for the framing of the organization or structure to come from multiple sources on the ground rather than from one overarching source.

It comes as no surprise, then, to read about the conflict to which the creation of the managing team (grilleuses) or the putting up of the daily grid was subject.9 Constant processes of collective negotiation and discussion took place. Nonetheless, conflict was vital in exposing dominant frameworks and making visible the power structures in play.

Local language and nonreductive semiotics

On this basis, it was paramount that the grid was discussed and negotiated among those affected by it. As Guattari comments, “it is useless to parachute someone into a task—especially if this is strategic—without his/her consent, without knowing how it is for him/her at that moment of the day in relation to the rest of his/her employment of time, and above all compared to what he/she would really like to be doing.”10 It is evident that the grid, described by Guattari as “collective analytic discursivity,” was much more than a mere rotational schedule. As the attribution of tasks and the rotation were subject to feedback and review, the grid itself shaped and systematically revealed the institutional processes that unfolded. In this manner, through changing and constituting the institution at the same time as in an evolving organigram, the grid was an instrument of collective institutional design. In essence, it had the virtue of singularizing the very trajectory of the institution with the ones of those living in it. Guattari further suggests that associated with the grid is the emergence of what he describes as a vibrant language, a language that would allow for the expression of the problems of the institution. As Guattari states: “[T]his system is connected with the invention of a language, with its own particular mode of naming different tasks, and a rhetoric that is particular to it, and that is the only way to treat certain problems […].”11 The fact that language played a crucial role in the institutional collective only makes sense if we understand how it served more than a mere technocratic function. By giving itself to the discussion of everyday life, language revealed in a pragmatic gesture its territories of conflict and production. This happens when the statement refers to more than itself, when it reveals the how, the where, and the why—or, to put it differently, its politics. In this regard, there are indeed references to the emergence of what is described as a “local language”12 in La Borde developing from the interchange of material and social tasks, technical and specialized knowledge, a collective learning of psychopathology. For instance, the use of psychiatric terms was adjusted and reviewed according to local use and the collective learning of psychopathology. There was also La Borde jargon (S.C.A.J. or Souscommission d’Animation de la Journée and B.C.M. or Bureau de Coordination Médicale are examples of this). This contrasts with the adoption of general semiologies and diagnostic manuals such as DSM,13 to give an example, which exemplify what could be described as a semiological axiomatization14 of the multiplicity of the mental and whose utility is hardly justifiable in terms of therapeutics. But this is just a part. Because, as I contended earlier, the successes of this specific form of “invention of a language,”15 as Guattari calls it, have little to do with language itself. Rather, they are to do with the fact that this is a particular mode of semiotization that is collective in nature and returns language back to the conditions of its existence in the first place. Language is cut open to dispute as part of a concrete existential situation that forces it to deal with broader pragmatics that exceed it.

In this sense, the relegation of the figure of the expert in institutional analysis is precisely an effort to stimulate a production of semiotization in relation to immediate and concrete problems. What was crucial was not the invention of a language but the creation of semiotization forums, as collective creations that could influence the transformation of the institution itself. Ultimately, it is important to draw attention to the articulation between collective discursivity and the organizational process—how the grid’s constant review would feed back to the institution itself.

The grid as the institution

Indeed, the grid was a formal organizational protocol that made use of a very basic and poor mechanism of quantification. The method itself was very minimal. As Guattari affirmed: “[T]he grid employs time inscribed on a piece of paper.”16 And yet it was a means to collectively create an institution. Rather than imposing a congealment of the creative ethos of the institution, the grid was an expressive formalization of this collective agency in time. In turn, this formalization acted on the institutional matter—that is, transforming it in a reciprocal presupposition.

This is where a function of collective semiotization enters—one that can be described as a semiotic praxis by groups and individuals; one that serves not a general axiomatization of problems of existence but a nonreductive formalization of collective life. For this to be so, it is critical that the meaning extracted from the grid’s quantification system is the responsibility of the collective forum that first set it up. To go a bit further, this capacity to self-guide semiotization processes is vital to the autonomy of the institutional collective. This fits Guattari’s description of a-signifying semiotics, which prescribes a type of relation between signs and things, by which the semiotic and the material connect diagrammatically, involving an existential production of the referent. Take the example of theoretical physics and musical notation. Here, signs are part of the material production and are in opposition to semiological redundancies that represent and offer “equivalents” of realities. In that sense, the grid can be understood as an essentially a-signifying protocol. As such, rather than casting pessimism into institutional processes,17 Guattari and Oury put forward an invaluable recasting of social and institutional practices. “A discussion of the process of institutionalisation has nothing to do with pre-established organisation charts and regulations,” Guattari writes: “[I]t has to do with the possibilities for change inherent in collective trajectories—evolutionary attitudes, self-organisation, and the assumption of responsibilities.”18 Such an understanding of the formal mechanisms and institutional processes that affirm the possibility of their nonreductivity and constitutive potential (one that does not subtract the multiplicity of the collective from its formalization) is still extremely relevant today. Much has been written about the mechanisms of reductive axiomatization and semiotization. But less has been said about how formalization processes—which are not an end in themselves—can be used to inform collective institutional processes that are not reductive in nature and can thus be openers and markers of important social and political change.