The Reed, Slime Mold, and Sprout

On becoming and the form of time

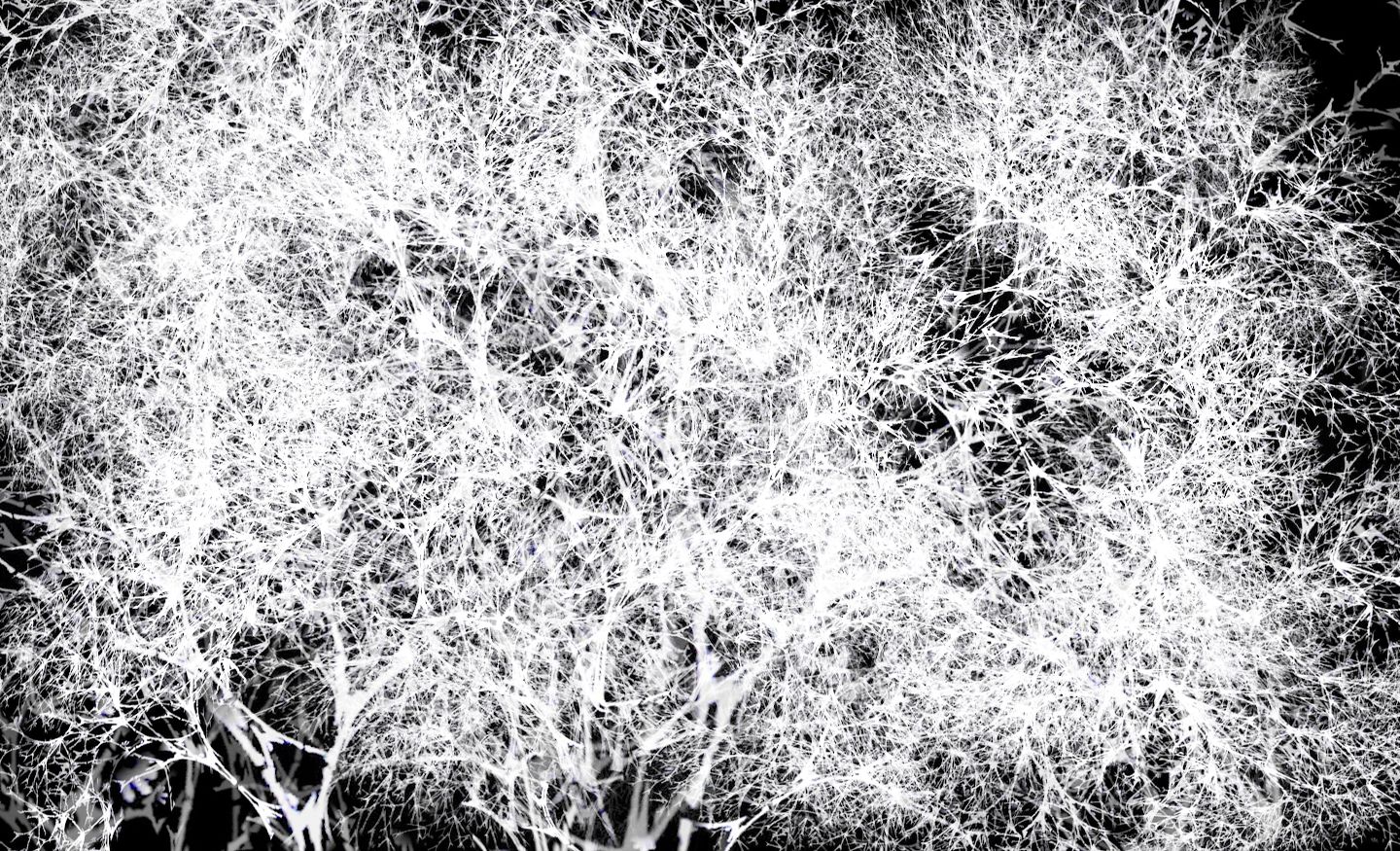

This essay, published during Anthropocene Campus 2016 and accompanied with video work by Delhi-based multimedia artist Rohini Devasher, explores the notion of history and meaning via ancient considerations of reed, slime mold and sprout. Through the lens of these curious strains of existence, Researcher Mashahiro Terada proposes a microscopic look at the concept of “becoming,” offering new ways of thinking required of us in the Anthropocene.

The Anthropocene makes us think. It makes us think about what history is and what development means. History is a notion, so it is a matter of the intangible, but at the same time history is a construction of concrete things and events. The Anthropocene requires thinking about not only the history of human beings, but also the history of the planet. When history is regarded as concerning human beings alone, its focus is on the product of human will, but when we think about the history of the planet, we confront the problem of how such a history is possible.

One of the entry points for this way of thinking about history might be a principle of becoming as opposed to the notion of being; the becoming focuses on the dynamics of change. It sees the modality of changing things. Change is intangible, although equally it can be perceived as tangible. Viewing the problem of becoming in a microscopic way, we may have an answer to the question of the Anthropocene.

Reed becomes.

At the beginning of the Shinto chronicle the Kojiki,1 the ancient historiography of eighth-century Japan, the reed appears on Earth as the first thing to exist. It appears in the process of the world’s becoming, thus the description of the reed has significant meaning in the history of the world’s beginning.

When heaven and the earth first began, in the heavenly plain, the god who was becoming was named ‘his majesty central major god of the heaven.’ The next god was named ‘his majesty high god of becoming.’ Then the next was called ‘godly god of becoming.’ These three gods were becoming as a single god, and they hid their body. Then, when the land was still young, looking like floating fat and drafted like a jerry fish, the name of the god who was becoming, like a shoot or the sprouting of a reed, was named the ‘god of beautiful shooting sprout.’ Then came the ‘god of everlasting heaven.’ Those two gods were becoming as a single god, and they hid their body. Then came the ‘god of everlasting land,’ and then the ‘god of wealthy clouds.’ Those two gods were becoming as a single god, and they hid their body. Then came ‘the god of mud,’ and his sister the ‘goddess of mud.’ Then came the ‘god of horn and stake,’ his sister the ‘goddess of vital stake.’ Then came the ‘god of huge gateway,’ his sister the ‘goddess of huge gateway.’ Then came the ‘god of sufficient,’ his sister the ‘goddess of respect.’ Then came the ‘god of coming,’ his sister the ‘goddess of coming.

At first, three gods appear: they are the god of the heaven and two gods of becoming. They are the world itself and existence will begin in the place, or venue, like actors coming onstage. The stage looks like a muddy and slimy circumstance. In such an environment, the first actor to appear is the reed, or the sprout or shoot of the reed. It is a symbolic meaning. The shooting sprout of the reed is the very first element of the world. The shooting sprout became the god. The notion of becoming, as the political theorist and philosopher Masao Maruyama points out, is a fundamental element of the Japanese narrative of history.2 He argues that from the time of the Kojiki, the Japanese historical narrative was dominated by the concept of a continual momentum of becoming, which lasted until the beginning of the post-modern age.

Is the reed metonymy or metaphor? As regards metonymy—that is, to signify something by naming it as something else—the reed is certainly part of the history of the world’s becoming. As the world’s character is represented by the reed as well, the reed is also a metaphor. The implication of the description of the reed is that history develops as the reed develops—both are relevant, which could be said is the primordial condition of historical writing.

Hegel believed that history developed through the function of the dialectic process. According to the ancient Chinese tradition, it was thought that history developed because of the order of the heavens. History, or historical narrative, needs motive power. The notion of becoming, therefore, can be seen as one of the motivating powers for the development of history. History moves forward, but what is the power of history? For ancient historians, history develops as the reed develops.

Slime mold becomes.

The development of history is not the only problem, for there is also the problem of the notion of history itself as related to the concept of becoming. How can humanity perceive of history itself? History is a notion, but also represents something that exists. Below, I investigate the notion of history from the perspective of Mandala thought and slime mold.

Mandala is a branch of Mahāyāna Buddhism.3 According to Mandala thought, things and the mind are inseparable, just as the inside and outside are also inseparable. According to Mandala thought, the world is consistent with the principle of Samsara, the cycle of life or rebirth, and the principle of Nirvana, the void. The world belongs to the Samsara Mandala, in other words; however, things that belong to this world are brought from Nirvana to become beings. Those two Mandala principles are closely interconnected. The essence of the Nirvana Mandala is a void; hence, the inhabitants of the world of the Samsara Mandala neither could perceive nor touch the Nirvana Mandala. The dynamic of becoming is based on these two Mandalas. Becoming comes from the void and has neither an inside nor an outside.

The Mandalas connect in multiple ways, and cannot be described in terms of a cause-and-effect relationship. They can be observed only as relative relationships, as in the case of quantum physics. According to such a worldview, the dynamic should be seen as a multi-relational network of functions as it cannot be seen through the logic of the function of cause and effect. It is necessary to understand the relationship itself. It is important to perceive all the various traffic of the many relations that make up the entire world; and in order to understand such a process, human perception should focus on the power of the process, or on the process itself.

Kumagusu Minakata (1867‒1941), a philosopher, anthropologist, and biologist, combined this Mandala theory with slime mold, or Mycetozoa in the early twentieth century.4

Slime mold is a curious strain of existence; it is a single cell. However, when it comes to the phase of the reproductive process, the mold transforms into a multi-cellular structure. The slime mold metamorphoses when they are in the moving phase; single cells congregate and move as if they are single organs. The way slime mold cells move is similar to an amoeba, but when the cells reach the reproductive phase, the cells metamorphose into a fungi-like shape, different to that of the amoeba.

For Kumagusu, observation of the Mycetozoa and the philosophy of the Mandala are best carried out on the same horizon. Like Plato, who develops his philosophy in the form of a dialog, Kumagusu develops his philosophical theory mainly in letters to his colleagues. In one of the letters, he argues for Mandala philosophy and Mycetozoa observation continuously.

When I was working with a microscope in the charcoal storage room in the midsummer, he [Taoism scholar Naoyoshi Tsumaki] came here and we talked about various things. I was observing the slime mold then, so I showed him it and compared it to the description of the ‘Nirvana Sutra.’5 This says that when the negativity in this world vanishes, the negativity in the other world will appear, as when a light is lit and darkness vanishes and when a light is turned off and darkness appears. […] [It is often said that Mycetozoa is sprouting when it metamorphoses into a fungi-like shape in the reproductive phase, but] the shapeless, insignificant, phlegm-like, and hence disdained half-fluid, the so-called original body, is the very living organism and the fruiting body of Mycetozoa, of which the protective spore is the only dead thing. It is a complete misunderstanding to say that when a fruiting body, i.e. a dead body, appears, that Mycetozoa is sprouting. It is also false to see the living organ of it, which does not have any particular body structure, and to say that the original body of Mycetozoa is dead.6

To Kumagusu, discussion about slime mold and the Mandala system was of equal value; or, to put it more precisely, what Kumagusu was thinking, his theory, had already appeared in the manner of the life of slime mold. In the 1930s, when Kumagusu was intensively observing slime mold, the scientific world did not know how to deal with such a way of describing life that was neither animal nor plant. This ambiguity bothered scientists, and the term Mycetozoa reflects the confusion, as the meaning of “myceto” is bacteria and “zoa” means animal. Of course, although ambiguity is best avoided in science, actually it exists, is our reality. Thus, in order to solve the ambiguity, Kumagusu turned to the Mandala theory.

History likewise is ambiguous. Normally history is thought of as an objective matter, but when thinking about history it is not so easy to decide whether it is objective or subjective. History is based on the principle of matter, which occurs in the world of objects; however, it is also a matter of the names that belong in the world of the mind. How can two categories be combined to become one? When we use the two Mandala systems as auxiliary lines, it can be said that a fundamental principle that enabled those histories to exist in the first place is by the very fact of the principle of the Nirvana Mandala. Becoming can be thought of as the other name of the becoming from the Nirvana Mandala into Samsara Mandala. The essence of becoming is based on the principle of the void. The difficulty in catching the becoming is that it comes from the void.

Sprout becomes.

Becoming relates to the ambiguity of our world. When we think about becoming, we must also think about what it means for our understanding of the world. The world is not a special place, but the place in which we live. Thus, the question arises as to what our ordinary world means. The Indian Mahāyāna philosopher Nagarjuna (c.150‒250 CE) thought about this question from the point of view of the sprouting shoot. In our world, plants sprout every day and everywhere. What does this mean? Nagarjuna explains the meaning of the sprouting in his own logical way.

The sprout is neither in the seed, its cause, nor in the things known as its conditions, viz., earth, water, fire, wind, etc., taken one by one, nor in the totality of the conditions, nor in the combination of the causes and conditions, nor is it anything different from the causes and conditions. Since there is nowhere an intrinsic nature, the sprout is devoid of an intrinsic nature. Being devoid of an intrinsic nature, it is void. And just as this sprout is devoid of an intrinsic nature and hence void, so also are all the things void because of being devoid of an intrinsic nature.7

When a shoot is sprouting, it is only sprouting. Sprouting is not the cause. Sprouting is not the condition. It is only sprouting. To sprout is a verb, and “is sprouting” is the predicative. No one can touch the verb “to sprout” or predicative “is sprouting.” It is only a matter of logic, and the logical world can only be addressed in logical terms.

Nagarjuna’s thought is based on the same system as the Mandala system mentioned previously. What he taught as the principle of the pratiya-samtpada (becoming by virtue of a relational condition) comes from the reality of our world. For him, the world consists of the principle of the relational condition, and the essence of the relational condition is a void (sunyata).

French philosopher Augustin Berque analyzes this point in detail and concludes that this logic, the middle way, could be a suitable alternative for the new era of the human environment.8 According to the dualistic view, “A is B” and “A is not B” cannot be compatible. It is the principle of the excluded middle. When we follow Nagarjuna’s view that “A is B” and “A is not B,” this therefore cannot be compatible; however, if the middle way is evaluated it could present an alternative to rethink the dichotomy. What the Anthropocene requires of us is to use the new way of thinking, of coming out of the dichotomy. In this sense, to look at becoming in detail might indicate an important lesson for us all.