The Technofossil Record: Where Archaeology and Paleontology Meet

The emergence of technofossils

Technofossils—human-made artifacts that can become part of Earth’s far-future geology1—have long existed, reaching back to the flint and bone tools of our distant ancestors. Over time, they have become more abundant and sophisticated, as shown by the archaeological record. And,since the mid-twentieth century, technofossils have gone through a phase ofparticularly explosive growth in abundance and diversity, many being made of novel materials such as plastics. With a mass now exceeding that of all of Earth’s living organisms,2 technofossils have become a planetary presence that we must better understand and deal with. The rivalry between the living and constructed realms goes well beyond a kind of face-off in mass equivalence: it becomes a war with many casualties, and the living side bears the brunt of it.

To understand the phenomenon of technofossils, we need to go further back in time to set the framework (or multiple frameworks). The very word “technofossil” is a reframing of the venerable term “artifact” to emphasize that many of these objects will enter the fossil record, and may be used—in the near or far future—like the traditional zone fossils, such astrilobites andammonites, thatpaleontologists use to age-date strata. Moreover, as these objects enter the fossil record, one can bring the dark arts of taphonomy to bear, forward-modeling how, and in what form, these objects will survive within strata over geological timescales. This, though, is not a simple exercise in telling catchy stories of the far future. The very act of fossilization means passing through, and interacting with, the living, sensitive “critical zone” that surrounds our planet. A plastic bag, for instance, might ultimatelyform a complex flattened impression in a bed of shale, reminiscent of (say) some exquisitely preservedjellyfish from Cambrian times. But, in passing from the surface to its ultimate burial, the bag may have choked a seagull, trapped some marine worms on the sea floor and, as a novel barrier to water and oxygen, formed different microbial micro-communities on its lower and upper surfaces that would react differently to the conditions of ever-deeper burial—before that subterranean life eventually winks out,millions of years later, several hundred meters below the sea floor. Technofossilization is therefore an active process, making its own living winners and losers in the critical zone. The process is complicated further in that humans not only manufacture complex objects, butassist in the fossilization process itself, for instance by emplacing such objects within tunnels and boreholes.

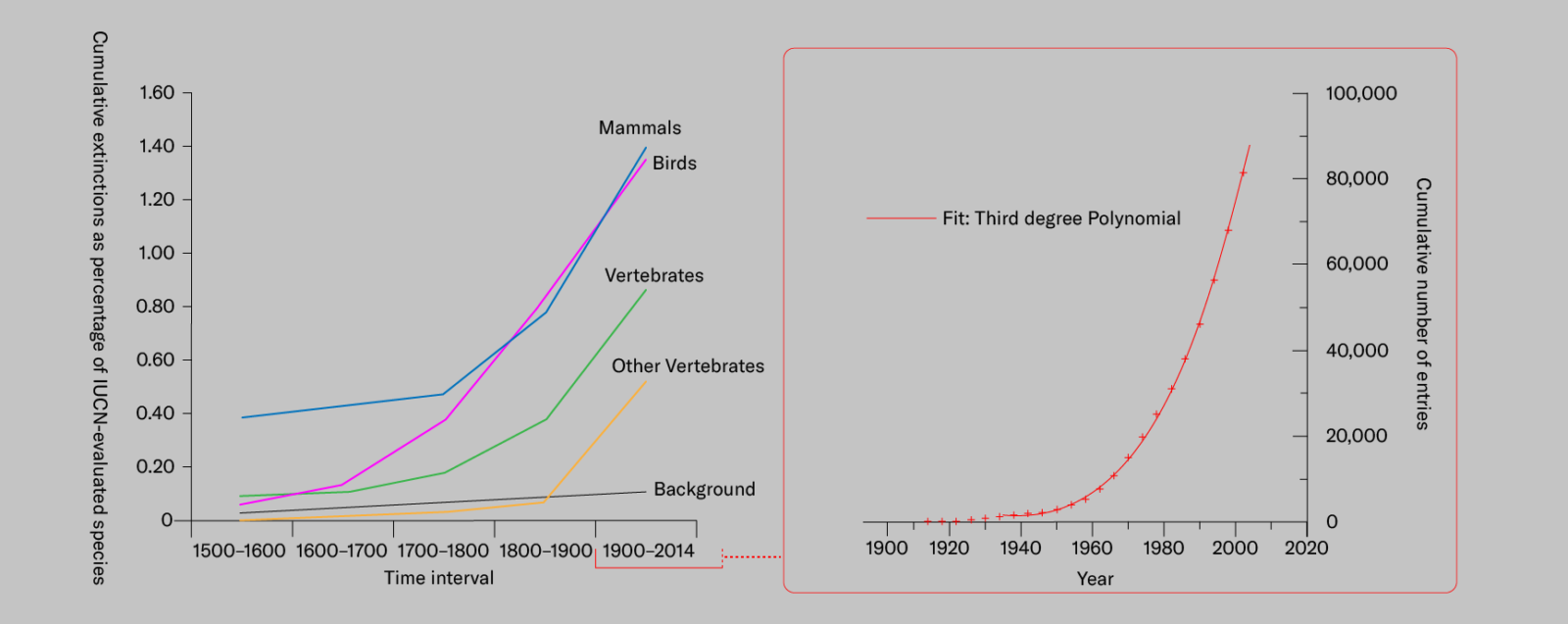

Two quite different kinds of data—biological species extinction rates taken from Ceballos et al. 2015, and rates of growth of new synthetic inorganic crystalline compounds (i.e. minerals in all but formal name) taken from the 2006 study of Behrens and Luksch. Graphs redesigned from Ceballos et al. 2015 and Behrens and Luksch 2006 by Luis Melendrez Zehfuss

A taxonomy for the archaeosphere

There are other perspectives that can be explored—that need, indeed, to be explored. Technofossils, that concept devised to encourage paleontological/geological analysis of our manufactured constructions, are still artifacts, and remain both central to and representative of the “material culture” of the discipline of archaeology. Here, the contrasts in methodological, analytical, and philosophical approaches between archaeology and paleontology might be fruitfully explored, with the aim of encouraging cross-collaborative discussions which would help us understand this enormous and rapidly evolving phenomenon. Archaeology has a long tradition and practice of collecting, classifying, interpreting, and curating artifacts of all kinds, a tradition almost entirely lacking in geology (except when collaborating—with archaeologists, naturally—on Pleistocene andHolocene strata). This knowledge and experience could usefully inform a paleontologist’s approach, whose natural reflex might be to try out Linnaean biological classification on technofossils, placing (for example) a Bic Cristal ballpoint pen species within a (large and diverse) ballpoint pen genus, within a family of pens (including fountain and felt tip pens), within an order of writing implements (in which pencils and crayons might be located), all these being within a phylum of communicative technology (which could inspire fierce discussions over whether or not it would include computers and televisions). Such an approach would be fascinating, if prone to being instantly overwhelmed by the huge scale and explosive growth of technodiversity—not to mention the cumbersome processes of biological taxonomy, which demands the formal selection of type specimens and the involvement of committees in nomenclatural changes for individual species. Taxonomic systems, however, reflect evolutionary patterns, and technofossil evolution differs from biological evolution, as we discuss below.

The archaeologists’ experience and traditions with this kind of material provide an alternative and complementary platform for coping with this challenge. And archaeology, while traditionally tasked with exploring the human world of the past—from ancient times prior to literacy up to historical times—now looks increasingly at the contemporary past, when the scale, speed, and nature of anthropogenic change accelerated. Thisfocus has led to pioneering archaeologically-based or -influencedstudies of contemporary “material culture”—for example, the analysis of the kinds of waste accumulating in landfill sites suggests thatthe modern, still-functioning world may be put under the same kind of microscope as in the studies of, say,Troy,Pompeii, orAngkor Wat. Geological studies also interpret modern waste and debris—but mostly on a large and relatively crude scale, where they are treated as sedimentary units to be mapped out, and their general properties assessed. Attempts to deal with the fine, technopaleontological detail contained within these deposits are just beginning, specifically as attempts to link waste and debris with still-functional constructions in same way that fossils are routinely compared with modern biological organisms. There is enormous potential to understand this phenomenon better in these kinds of ways—even as our contemporary material culture continues to grow and evolve around us.

Archaeologists traditionally deal with technofossils made of novel materials—pottery, glass, concrete, brick, tile, and now increasingly plastics and other modern materials—which are commonly found as inclusions in archaeological strata. These are used to date and correlate layers and features in ways broadly analogous with how geologists use fossils of natural organisms. However, methods of stratigraphic analysis have to be adjusted somewhat to take into account important differences between technofossils and “natural” fossils. An obvious point is that whereas the evolution of biological organisms is determined by natural selection acting upon the physical expression of genetic coding, technofossils are subject to cultural selection pressures and only indirectly to forces of natural selection. This can lead to significant differences between their patterns of distribution in the stratigraphic record. Another difference is that the processes of fossilization through which the remains of natural organisms get to be preserved in strata might, in classical geology, be considered entirely natural. However, in the case of technofossils, these processes may be technological as well, with questions of the intentional design or cultural style coming into play. A brick is a good example: first made from clay molded into a required shape and heated in a brick kiln, it spends its useful life in the functioning technosphere as part of a structure, and afterwards it might end up in urban archaeosphere layers of accumulated occupation debris and building rubble, or be deposited back in the ground as landfill. The brick does not need to wait millions of years for geological processes of lithification (hardening) to occur: It has already been turned to stone, in a kiln rather than in sedimentary settings, with a strong potential for long-term preservation as a fossil on geological timescales. Thus even its entry into stratigraphic contexts is culturally and technologically mediated.

Archaeological methodologies have evolved to deal specifically with such objects and materials, and take due account of the factors described above. Typologies and seriation charts used for pottery can be adapted for use with other novel materials, such as plastics. Of particular consideration is the technofossil within its stratigraphic context. The information it can convey is—as with fossils in ancient strata—multiplied many times by taking into consideration the total assemblage of technofossils and novel materials along with other environmental evidence, such as animal bones found together in a particular layer, and the position of that layer within a broader stratigraphic sequence of archaeological cuts and deposits. The technofossil has potential to reveal information not only about itself and its own mode of manufacture or use, or about the layer within which it was found, but also about larger structures and features in the archaeological record. A single technofossil or novel material such as a fragment of pottery (which can be dated by reference to similar pottery found in other correlatable contexts)—if it is found beneath a wall or in a layer cut by building foundation trenches—can help to date the whole building or complex of buildings (just as a single trilobite fragment can date a stratal succession to a precise level in the Palaeozoic) and at wider levels, provide information on patterns of trade.

Twentieth-century technofossils in inundated landfill deposits at East Tilbury on the River Thames estuary. The landfill is being eroded by tidal surges as sea level rises. Here are objects of glass, ceramic, brick, tile, concrete, etc. Lighter materials such as plastics have been carried away by the tides, leaving heavier items behind. Photo by Strat188, wikimedia

Technostratigraphy in the Anthropocene

There is a difference though, in scale if not fundamentally, between thepottery shards of thousands-year-old civilizations and, say, modern polyethylene bags, ballpoint pens, and the plastic shafts of cotton swabs. Those pottery relics provide marvelous time constraints, which can typically date the cultural evolution of particular local civilizations, together with those that they interacted with along evolving trading routes. The timescale produced is a patchwork of local to regional ones, that one correlates as best as one can, usually with the help of numerical proxies such as radiocarbon dates.Modern plastic implements, invented only decades ago, have spread around the world with astonishing speed, first along modern global trade networks, and then once they were discarded, scattered by wind, flowing river waters, and ocean currents—and within the bodies of animals that had eaten them—to become truly global temporal markers. Some, like theplastic fibers discarded from modern clothing, are so abundant that they have become a key signal, routinely sought (as “micro-technofossils”) in the core specimens being analyzed as potential candidates for the Anthropocene “golden spike.” One might consider thefly ash particles also routinely analyzed for the same purpose as another“micro-technofossil,” as they, too, are the byproducts of an industrial process.

Most technofossils provide very fine dating resolution, not only for identifying theAnthropocene, but also to signal a discrete level within it. Among the modern polymers which are produced and consequently discarded in large amounts around the globe, one might consider, for instance, those under the polyethylene (PE) umbrella: there are dozens of polymer types (LDPE, HDPE and many others) that have been invented within decadal timespans and might representfine-scale chemostratigraphical markers within Anthropocene strata.3PET (polyethylene terephthalate) bottles, now ubiquitous, were first produced in 1973, and so date what one might now term the mid- to late Anthropocene. Of course the patterns into which plastics have been shaped infinitely multiply the dating possibilities.The plastic credit card andthe Bic Cristal ballpoint pen, for instance, both first produced in 1950, may be regarded as zone technofossils for the Anthropocene, whilecompact discs (surprisingly widely dispersed as trash) only date from 1982. The technostratigraphic possibilities are almost endless, as technodiversity (if measured as the number of specific kinds of technofossil) is now far greater than biodiversity, measured as the number of species.4 The larger technofossils are not quite as ubiquitously distributed, of course—but then paleontological macrofossils such as ammonites and trilobites are also not as ubiquitous in strata as are microfossils such as fossil pollen and micro-algal sporecases; indeed, many macrofossils are rare, and yet they are avidly sought by paleontologists for their great value as markers of geological time. One may expect similar utility for technofossils, both small and large, once efforts to seriously map and classify Anthropocene strata get under way.

Technofossils and the evolution of information

Technofossils, and the new materials of their construction, are just the residue of a process—or rather, of many variably interlinked processes and forces: supply chains, investment hubs, research institutes, factories, courts of law, pubs, power stations, football stadiums, prisons, advertising agencies, army barracks, farms, across the garden fence, and in other countless and diverse nodes of human influence and action that combine within the technosphere. In the same way, biofossils are the residue of a network of interlinked biological and geological processes that, together, define the biosphere and underpin its actions.

As high tides and storm surges erode the landfill deposits at East Tilbury, sheet plastics dumped in the 1980s emerge from the low receding cliffs, to be swept out onto the river and eventually out to sea. Such modern forms of plastic are found only in the upper layers. Lower layers contain earlier forms of plastic such as bakelite. In fact this landfill, started in the late nineteenth century, may comprise a stratigraphic record of almost the entire history of plastics. Photo by Strat188, wikimedia

One way of tying together the stratigraphic classification of objects as different as biofossils and technofossils is to take advantage of the fact that both indirectly record steps in the evolution of knowledge. The role of knowledge merits attention because it plays a central role in the appearance of technology, and thus in the emergence of the technosphere from the biosphere.5 Knowledge can be understood as information that has causal effect, and that has the potential to evolve by transforming itself and its environment in a way favorable to its own survival.6 This physical definition applies to information in DNA, which propagates according to Darwinian mechanisms and, in the process, helps construct its immediate environment (the organism itself) and alter its surroundings (niche construction) in a manner that enhances its own survivability. One of the products of the evolution of non-cognitive genetic knowledge was the human brain, an organ able to create and store causal information in patterns of neural synapses. Lacking the Darwinian constraint to replicate itself accurately, such human cognitive knowledge was able to evolve and impact the world in a way relatively unconstrained by biology.

The escape of knowledge from biological control created in its wake a new force in Earth history: technology. The resulting flood of technological artifacts with their information-rich patterns of form, composition, and connectivity initiated yet again a new cycle of knowledge creation, i.e., the knowledge embedded in technology. This process resulted in human-technological networks, patchy and widely scattered at first, that grew and merged to produce,by the late eighteenth century, a new, globally integrated Earth system.7 This system constitutes the technosphere, where “sphere” indicates the presence of many qualities common to the classical Earth spheres, i.e., the atmosphere, hydrosphere, lithosphere, and biosphere.8 The production and deposition of chemical, particulate, and artifactual waste by the technosphere, including many novel forms,accelerated markedly from the mid-twentieth century onwards, giving rise to unique, preservable, and globally distributed technofossil assemblages.These help allow practical recognition of the Anthropocene within recent strata.

The characteristic entities of the technosphere and biosphere, i.e., artifacts and organisms, can serve as durable proxies for the underlying technological and biological information they contain as they provide the raw material for fossilization. Changes in organismal information, transmitted between generations via Darwinian evolution, most commonly result in only incremental differences in organismal body design. Although DNA information tends to fade with time after an individual organism dies, corresponding structural information can persist in the architecture of biofossils. Where the resulting biofossil record is locally non-incremental, one may infer that the discontinuity is due to causes such as erosion, rather than to a sudden change in organismal design.

In contrast, technological artifacts, enabled by the fluidity of information freed from the chemical bondage of DNA, can evolve rapidly in giant Lamarckian-like steps, leaving a technofossil record marked by discontinuities that reflect the saltatory nature of technological change. As a consequence of these jumps in design, the resulting technofossils cannot be relied on to carry with them intrinsic evidence of their temporal relationship to earlier technofossils. Information missing from the technofossil record must be provided from an independent but correlatable data repository. Such an external record, as compiled for example from archaeological findings and the history of technology and science, offers a stand-in for the continuity that characterizes biological change. The required external record, residing for example in the cultural knowledge in books, universities, and museums, and in the cognitive knowledge in the brains of living scientists and historians, is a product of the technosphere. Thus the evolution of technological knowledge, in addition to generating a cryptic sequence of technofossils, also provides, in a continuously updated form, the key to deciphering the technofossil text. This makes it possible to avoid ad hoc organizational schemes for the classification of technofossils, such as those based on form or inferred function, and instead to adopt a cladistics approach similar to that in biology, i.e., an ordering system that respects the causal chain connecting successive generations of technology.

The necessity of relying on cultural information for understanding technofossils is not a sign that technofossils should be unacceptable as part of the geological record. Indeed, biofossil classification is similarly dependent on knowledge residing in the technosphere. The extension to technofossils simply reflects the fact that in the Anthropocene, cognitive and cultural knowledge has influenced planetary dynamics sufficiently rapidly and profoundly torequire updated stratigraphic charts and protocols. This points to the fact that stratigraphy must be a living, growing science if it is to keep up with the pace of planetary change.

Human-led mineral evolution, concrete, metals and the plastics connection

The novel materials used in these constructed objects are as astonishingly hyper-diverse as the objects themselves. That the number of types of inorganic crystalline compounds—minerals in all but formal classification—multiplied forty-fold over a figure that hadheld more or less steady for two and a half billion years is impressive enough. The mineralogist Bob Hazen and his colleagues have both beautifully set out the geologically slow pace of mineral evolution on Earth,9 and then detailed its late but strikingly impressive human addition.10 To have nearly all of that novel,human-driven diversification taking place in the last 70 years seems surreal, like something out of science-fiction.11 Most of these new compounds are present in tiny amounts, of course—but then, most natural mineral species are extremely rare too; only a few dozen make up the bulk of rocks on Earth.

However, the mere presence of a novelty may not really count for much in the Earth System, if its effect on that system is slight or benign. The most abundant novel material on Earth, by a wide margin, isconcrete, at something exceeding half a trillion tons—about half this weight was produced inthe last 20 years. Yet concrete is a rock, a little like a sandy limestone, generally inert if not altogether non-toxic (through its highly alkaline nature). Large amounts of pure (or alloyed) metals have been brought to Earth’s surface, like iron, copper, and aluminum—the metals themselves are not generally regarded as pollutants (although the separation of these metals from their native ores may be highly polluting). Plastics, though, are something different.12 Even though they are among the most chemically inert of all of the novel materials, their relative inertness, combined with their strength and lightness, is exactly what makes them so troublesome.

Plastic bags can be blown like leaves by the wind, reaching places far away from their initial sources. As discussed above, when landing in the soil, bags do not mulch down as leaves do, but just… remain. If buried and out of the reach of UV radiation from the sun, they might stay intact for decades, centuries—or perhaps even longer, even while being disturbed by the action of worms, moles, and percolating water, and slowly shifting their position via soil creep and other mass movement processes. Although this kind of long-term longevity is an open question, current evidence suggests that plastics can be preserved at least within human timescales, and for some perhaps far longer;amber, after all, has no problem surviving, buried in strata, on multimillion-year timescales. That is, however, not surprising, because plastics are resistant to most forms of degradation by design. Plastics are manufactured to be durable, and most of the plastics that now migrate between different environmental compartments are not those with long lifecycles, such as machines and vehicles or the fridge in your kitchen, but those with short lifecycles, such as the plastic bag blown away by the wind. If at the surface and attacked by UV radiation, plastics simply fragment into smaller pieces of plastic which can stay there or travel on. In general, the smaller the fragment of plastic, the higher its potential to be transported within and among compartments. This very mobility has allowed microplastics (<5 mm) to become a ubiquitous component of the surface layers of all ocean sediments, even in remote regions or at profound water depths. This means that in all oceans aplastics-rich sediment layer is forming, one that has never occurred before in the entire history of our planet. On land, a large proportion of contemporary agricultural soils is also heavily polluted with microplastics which have been spread through the application of organic compost and sewage sludge. The hyper-rapid evolution in plastic polymer technologies (PET, PP, PVC etc.) can even record decadal shifts in abundance that may date post-1950 sediments, as we have shown above. Some plastics might even be considered extinct.Bakelite, for instance, may be considered an ancient polymer type, as it is more than a century old, and its current production rates are negligible when compared tomore modern polymers.

It is hard to think of a geological equivalent, physically or chemically, for plastics. As larger fragments, amber and related solid hydrocarbons come close, but they are too rare to have wider environmental impacts. The tough natural polymer coats of pollen and spores could make good analogues for microplastics, but millions of years of evolution has enabled biological digestion processes to evolve which can break down these materials—not least by honeybees, which can use pollen as a primary food source (one, these days, sometimes hijacked by health-conscious humans). One might have to go to other planetary bodies to find analogues for abundant, undigested polymerized hydrocarbons at the surface—such as Saturn’s moon, Titan, where such solid particles are thought to make up the spectacular wind-blown dunefields there. In many ways, plastics are an alien material for Earth, and developing an effective conceptual framework for plastics is one of the challenges they present us in the Anthropocene.

A technosphere in overdrive

Technofossils, whether of plastic or of other materials, are at a stage of development that gives much food for thought. Their ever-faster increases in bulk and sophistication, as a key component of a technosphere in overdrive, take place largely at the expense of a diminishing biosphere, amid a heating climate and rising sea levels that may be also counted as spin-offs of the technosphere’s construction. Will that furious evolution continue, as new forms spring up to help their parent humans cope with, and perhaps ameliorate, an increasingly perilous environment in this new kind of arms race? Or will the technosphere, and its cornucopia of material inventions, be choked off as its biological foundations give way underneath it? Or might technofossils even dispense with their biological foundations to become wholly silicon-based, sustaining themselves on a Hothouse Earth inimical to complex organic life? That last option still seems a little out of reach, but one never knows. In whatever form, this story looks like it will still develop some fascinating, if not always comforting, chapters.

Jan Zalasiewicz is a field geologist, paleontologist, and stratigrapher. He teaches various aspects of geology and Earth history, and his research on fossil ecosystems and environments, spanning over half a billion years of geological time, includes study of the Anthropocene concept.

Peter K. Haff is professor of Geology and Civil and Environmental Engineering in the Division of Earth and Ocean Sciences and in the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University, North Carolina. His research focuses on the role of technology in the Anthropocene

Matt Edgeworth is Honorary Visiting Fellow in the School of Archaeology and Ancient History at the University of Leicester, UK.

Juliana Ivar do Sul is a researcher working at complementary aspects of (micro)plastic pollution in the environment. For many years she has explored environmental fates of plastics in the sea, and now focuses on their potential as markers of the Anthropocene.

Daniel Richter is Professor of Soils and Forest Ecology at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University.

Cover art by Protey Temen, © all rights reserved Protey Temen

Please cite as: Zalasiewicz, J, P K Haff, M Edgeworth, J Ivar do Sul, D Richter (2022) The Technofossil Record: Where Archaeology and Paleontology Meet. In: Rosol C and Rispoli G (eds) Anthropogenic Markers: Stratigraphy and Context, Anthropocene Curriculum. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. DOI: 10.58049/e1bg-ab83