The Vietnamese Community in Eastern New Orleans

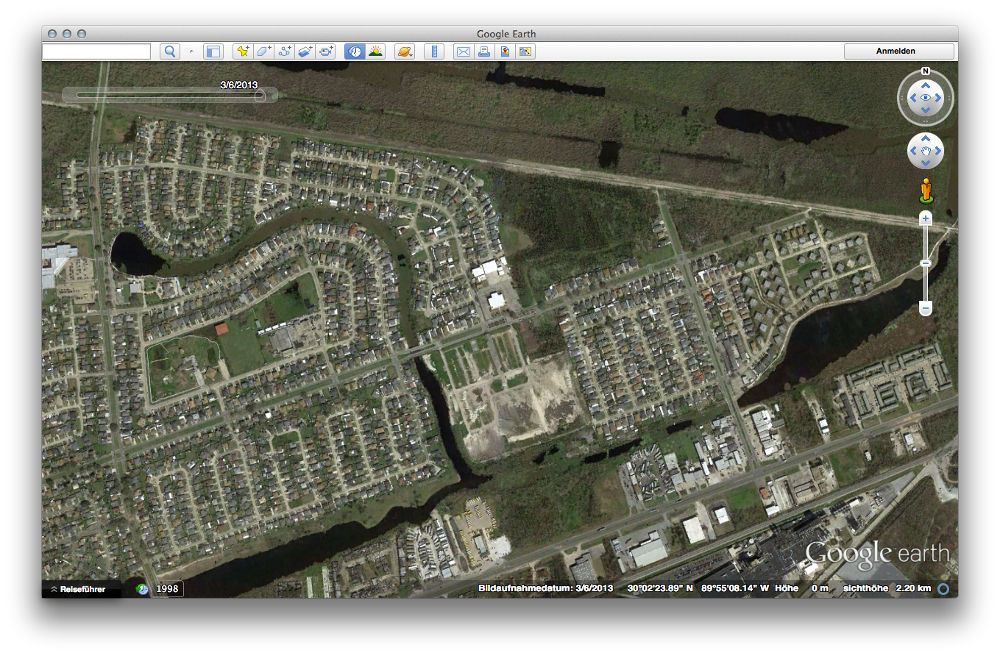

This case study looks at the Vietnamese community in Versailles and Village de l’Est, areas in Eastern New Orleans with the largest Roman Catholic Vietnamese congregation in the United States and one of the densest Vietnamese concentrations anywhere in the country. Today, there are about 8,000 inhabitants of Vietnamese descent, who constitute the physically isolated and intensely clustered suburban community.

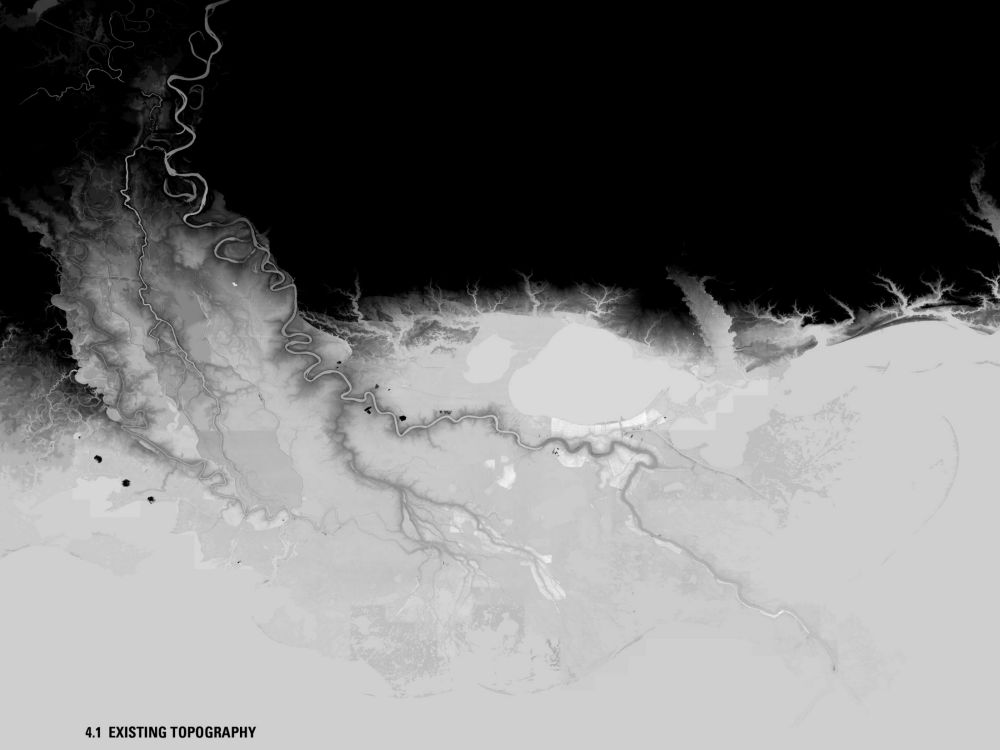

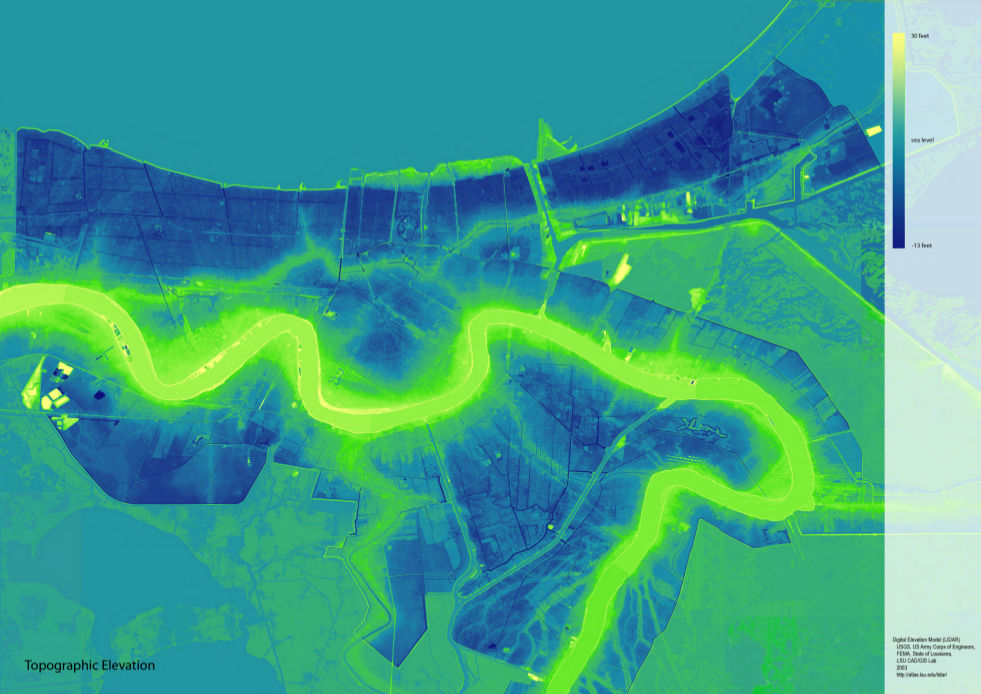

In the 1950s, Eastern New Orleans was mostly rural except for services along Chef Menteur Highway. The intercoastal I-10 was built through New Orleans between 1963 and 1972. In the early 1970s, the area was aggressively developed and swampland was drained to make way for suburban habitation. The drainage system, which was put in place before development began, was designed in such a way that it could store heavy rainfall runoff better than in New Orleans and its western counterpart, where similar development had started around ten years earlier. In 1965, Hurricane Betsy caused severe wind damage and flooding in and around Eastern New Orleans. The Flood Control Act of 1965, when ratified, put the federal government in charge of storm protection. With the newly constructed I-10, the envisioned and implemented flood protection, the Industrial Canal, the NASA Michoud plant, and new subdivisions, the “New Orleans East” development scheme profited greatly from increasing real-estate values throughout the oil-boom years. The intercoastal I-10 helped convert an area previously considered unfit for habitation into a vast suburbia.

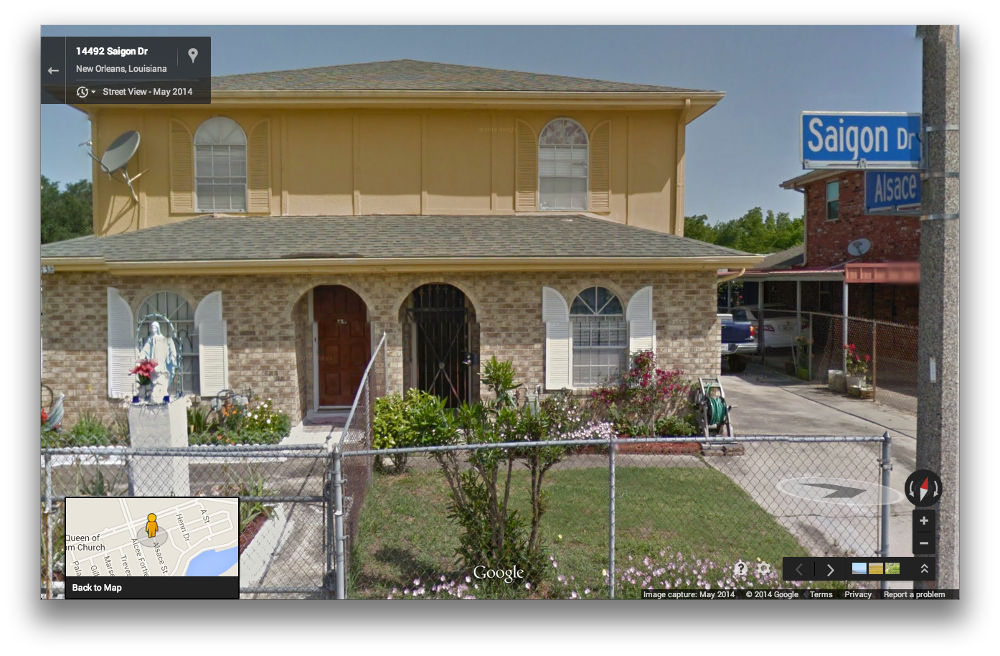

The common ground between New Orleans and Vietnam is not only their environmental semblance in terms of a semitropical climate and fishing opportunities. Less obvious is that they both share a strong Roman Catholicism, in both cases introduced by the French. Although prosecuted by the government, Catholicism thrived in Buddhist Vietnam. Following the communist victory over the French in the First Indochina War (1946‒54), Vietnam was partitioned into two states: North and South. North Vietnam was under the rule of Ho Chi Minh and became increasingly hostile territory for Catholics. This resulted in an exodus of Catholics from North to South Vietnam over the following years. The refugees settled in the Mekong Delta and in and around Saigon. They established self-contained hamlets protected against the communists by palisades and with statues of the Virgin Mary and Vatican flags to reconstruct a sense of the past. The end of the Vietnamese War and the fall of Saigon in 1975 led to the reunification of Vietnam under socialist rule and to the second exodus of Catholic Vietnamese, from both rural and urban areas. The United States military supported and brought refugees to four US military bases, in California, Florida, Pennsylvania, and Arkansas.

Led by a federal Catholic organization and following their criteria (of a good economy, an existing Vietnamese community, higher welfare benefits, and warm weather), relief agencies nationwide were sought to support these efforts by providing potential settlement sites for the Catholic refugees. Of the criteria, New Orleans could not fulfill more than a semitropical climate, but it offered advocacy by a strong relief agency that practiced the same conservative, Vatican-reverent Catholicism as the Vietnamese. The Associated Catholic Charities invited Vietnamese families from a US base in Florida to settle in New Orleans. They sponsored apartments in the “Versailles Arms”—an apartment complex on the periphery of the city—that happened to be available despite a housing shortage and due to layoffs at the Michoud NASA facility nearby.

The “first wave” of about 3,000 Catholic Vietnamese immigrants arrived in Eastern New Orleans between 1975 and 1977. They were mostly middle-class anti-communist political refugees, so-called “elites.” The “second wave” of refugees or “boat people,” most of them poor rural farmers and fishermen, who had left Vietnam by boat, arrived after 1977 and throughout the early 1980s. A further wave of immigrants in the 1980s and 1990s may have chosen the site perhaps due to its physical appearance, but had there not been an established Vietnamese community already, they might never have arrived there.

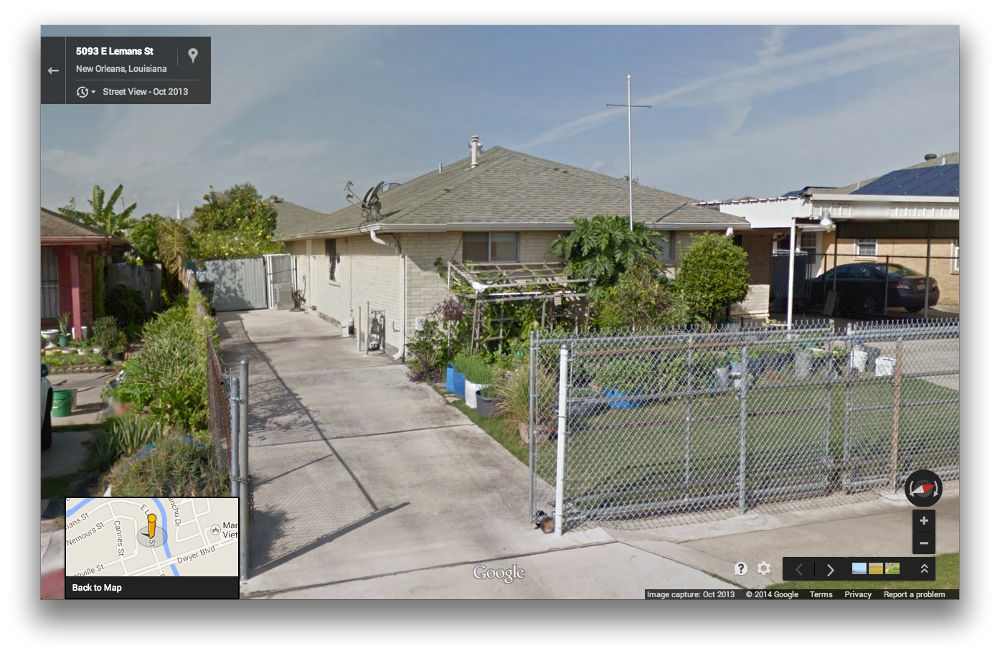

The refugees commenced gardening shortly after their arrival in 1975. Lawns, front-, side-, and backyards as well as the banks of the Michoud Bayou are cultivated with tiny to elaborate poly-cultural market gardens, creating an agrarian landscape that is reminiscent of their former setting. If it had not been a suburban area, the tradition of gardening may never have occurred. Some of the gardening within the Versailles Arms complex was disapproved and had to be relocated outside the area protected by the levee, where forest was cleared for agricultural land (according to Richard Campanella, the last example of land-use transformation from forest to agriculture on East Bank New Orleans).1

Further reading and sources

Campanella, Richard, Bienville’s Dilemma: A historical geography of New Orleans. Lafayette: Center for Louisiana Studies, 2008.

Fontenot, Anthony, Jakob Rosenzweig and Anne Schmidt, project and exhibition: “Exposing New Orleans.” Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 2005, online (accessed 11/12/2015).

Lewis, Peirce F., New Orleans: The making of an urban landscape. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing Company, 1976.

McMichael Reese, Carol, et al. (eds), New Orleans under Reconstruction: The crisis of planning. New York: Verso, 2014.

Rosenzweig, Jakob, “Reinventing the Mississippi River Delta: A flood of creativity,” diss. MA Architecture. New Orleans: Tulane University, School of Architecture, 2007.