Too Little Water: The Lake Chad Story

Lake Chad, in the arid and semi-arid Sahel corridors of west Central Africa, represents one of Africa’s greatest life forces. The lake’s water-based, life-supporting services support an integrated small-scale economy made up of agricultural livelihoods, and provide a lifeline to over 30 million people in four countries (Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria).

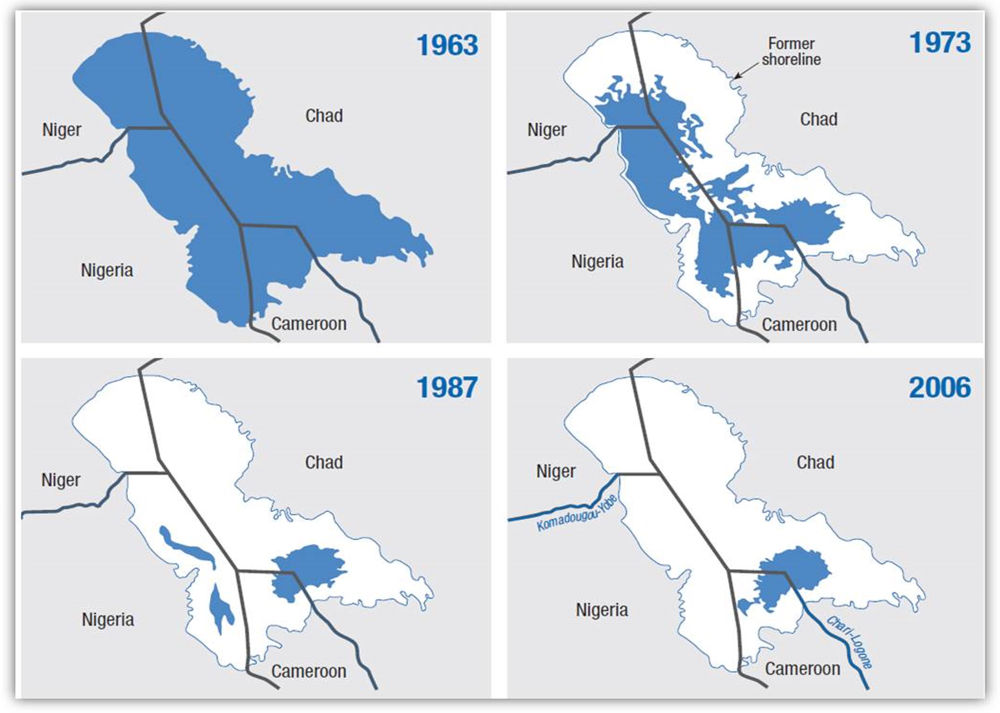

Since 1963 to date, more than 90 percent of the lake’s waters have disappeared, largely because of changes in climatic conditions and increased human demand for irrigation farming, livestock herding, artisanal fishing, and power generation. Images of its progressive diminution (from about 25,000 km² in the 1960s to less than 1,350 km² today); of lakeside communities whose sources of livelihood are declining; of droughts, deprivation, and conflicts dominate expert understandings of current conditions in the Lake Chad region. These conditions, acting alongside institutional weaknesses and government failures, constitute the key drivers of vulnerability and insurgency in the region. Conditions in Lake Chad provide a dynamic test bed of broad relevance for understanding mainstream human‒environment linkages, particularly in relation to the subjects of sustainability and resilience in the Anthropocene. Sustainability in this sense encompasses the need to recharge the lake and restore it to a level where it can continue to sustain local livelihoods and regional economies. Where this is not possible, then proactively upgrading the resilience of the locals will be necessary. This can be realized by enhancing the capacity of lakeside communities to create alternative livelihood options and to seek strategies that would increase their competence to confront emerging threats associated with the degradation of Lake Chad.

Further reading: Uche T. Okpara et al., “Conflicts about water in Lake Chad: are environmental, vulnerability and security issues linked?,” Sustainability Research Institute of the School of Earth and Environment, No. 67. Leeds: University of Leeds, 2014. Online; and in: Progress in Development Studies, vol. 15, no. 4, (2015), pp. 308–25.