Uncalculated Risk

A brief history of New Orleans' Industrial Canal Lock

Residents of New Orleans and the city’s surrounding parishes are no strangers to the role large-scale infrastructural projects have played in heightening risk while reducing equity in the region. In this text, two local community advocates, architectural historian Jeffrey Treffinger and John Koeferl, president of Citizens Against Widening the Industrial Canal (CAWIC), provide a brief history of expansionist projects undertaken by the United States Corps of Engineers in the area, demonstrating how many of today’s endeavors are rooted in now obsolete ideas from the past. In doing so, the authors argue that it is only by abandoning these outdated approaches, which typically favor the needs of industry over citizens, and engaging with the challenges of the current era that the rising tide of planetary change can be stemmed—not only in the case of New Orleans, but everywhere.

An ariel view of New Orleans taken c.1950, showing the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal (known locally as the Industrial Canal) in the top left. Image source Team New Orleans, US Army Corps of Engineers, (CC BY 2.0)

The United States Corps of Engineers is currently asking Congress to pour billions of dollars into the expansion of a failed, hundred-year old dream to move New Orleans shipping activity from the Mississippi to the tidewater area between the River and Lake Pontchartrain. The Corps is determined to build a new navigational lock complex in what is known locally as the Industrial Canal. This 5.2-mile Canal with its historic lock and bridge complex was completed in 1923 and for the first time, artificially connected Lake Pontchartrain to the Mississippi River. The Industrial Canal expansion is expected to last 15-years and cost over a billion dollars by Corps estimates. In reality, if this expansion follows other Corps projects of similar scale and scope it will take much more time and money than they originally considered. This project will likely significantly impact the health and well-being of area residents and disrupt, if not destroy, the economic development of the surrounding neighborhoods. It will likely snarl commuting between Orleans and St. Bernard Parishes and could impact essential hurricane evacuation routes. It is an idea that has no relation to its time and place, posing a regional threat by allowing another commercially driven federal project to ignore the community it will impact.

While New Orleans is confronting this project in 2020, Congress originally authorized a replacement lock for the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal (IHNC) in 1956. Since then, the project has been delayed by neighborhood grass root opposition, environmental lawsuits, Hurricane Katrina, and the Corps of Engineers own vacillating and incomplete designs. The 1956 Congressional authorization included funding for the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO): a laser straight, forty-foot deep artificial channel dug through the mud of the marsh and designed to speed mari-time between the Gulf of Mexico and the Port of New Orleans. The 1956 Congressional authorization also required a fifty percent local fiduciary partner to match federal funds for improvements to the IHNC and the digging of MRGO. At that time, this local partner was the Port of New Orleans. The context of the proposed IHNC lock expansion project must be viewed through the lenses of a community and region that coexist with water. The history of projects to control this water for economic gain are littered with side effects that have been disastrous to the landmass of Southeastern Louisiana and the people who live there.

The original vision of the Port of New Orleans was to somehow do what nature had never done: connect Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi River by digging a canal and building navigational lock to mitigate the differences in water levels. The Industrial Canal and Lock complex were completed in 1923 with the intent of concentrating barge and ocean-going traffic in this more predictable tidal zone rather than on the unpredictable riverfront. In 1927, not long after the completion of the canal and lock, heavy spring rains and snowmelt from the North raised the Mississippi River to unprecedented levels. This was perceived as a threat to New Orleans bankers and Port officials who feared the new lock would be overtopped by water. Port and City officials agreed to breach the Mississippi River levee below New Orleans in order to save the City. As a result, St. Bernard Parish was flooded and thousands of people were hurt and left homeless. The region’s fishing and fur-trapping economy were devastated. There was no form of compensation given to Parish residents. It is well understood that there was very little chance of New Orleans actually flooding in 1927 and this levee breach was done to show the rest of the nation that New Orleans could control its river.

As the Port of New Orleans grew to one of the largest in the United States, there were two deficiencies seen as impeding economic expansion. The IHNC lock was allegedly becoming a bottleneck in the system because of its inadequate size. In addition, the meandering ninety-mile journey between New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico took a lot of time (and fuel). The 75-mile MRGO was completed in 1965 and coincided with Hurricane Betsy. During that massive storm, extensive areas of St. Bernard Parish and the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans were flooded like never before. To area residents, something had fundamentally changed: the storm surge historically buffered by wetlands, was now in their homes and had a clear connection to the existence of MRGO. At the same time, the Eastern side of the IHNC flood wall failed allowing the storm surge in Lake Pontchartrain to enter the Lower Ninth Ward: a black working-class neighborhood. There was massive flooding, loss of life, and devastating property damage in this neighborhood that also had the highest percentage of owner occupied housing in the city. A significantly more horrible version of this same story was repeated in 2005 with Hurricane Katrina.

The people who were encouraged to settle along the IHNC bore the brunt of these bad water management decisions. The Desire and Florida Avenue housing projects were built on the Western side of the IHNC to provide residences for the labor force anticipated by the Port to staff their activity on the Canal. In reality, cargo handling became more mechanized during the 1960s and these jobs never materialized. The people who occupied these housing developments were marginalized and isolated from the rest of the City. Poorly constructed and in low lying areas, the Florida and Desire developments fell rapidly into disrepair and were all but abandoned after Hurricane Katrina flooded them.

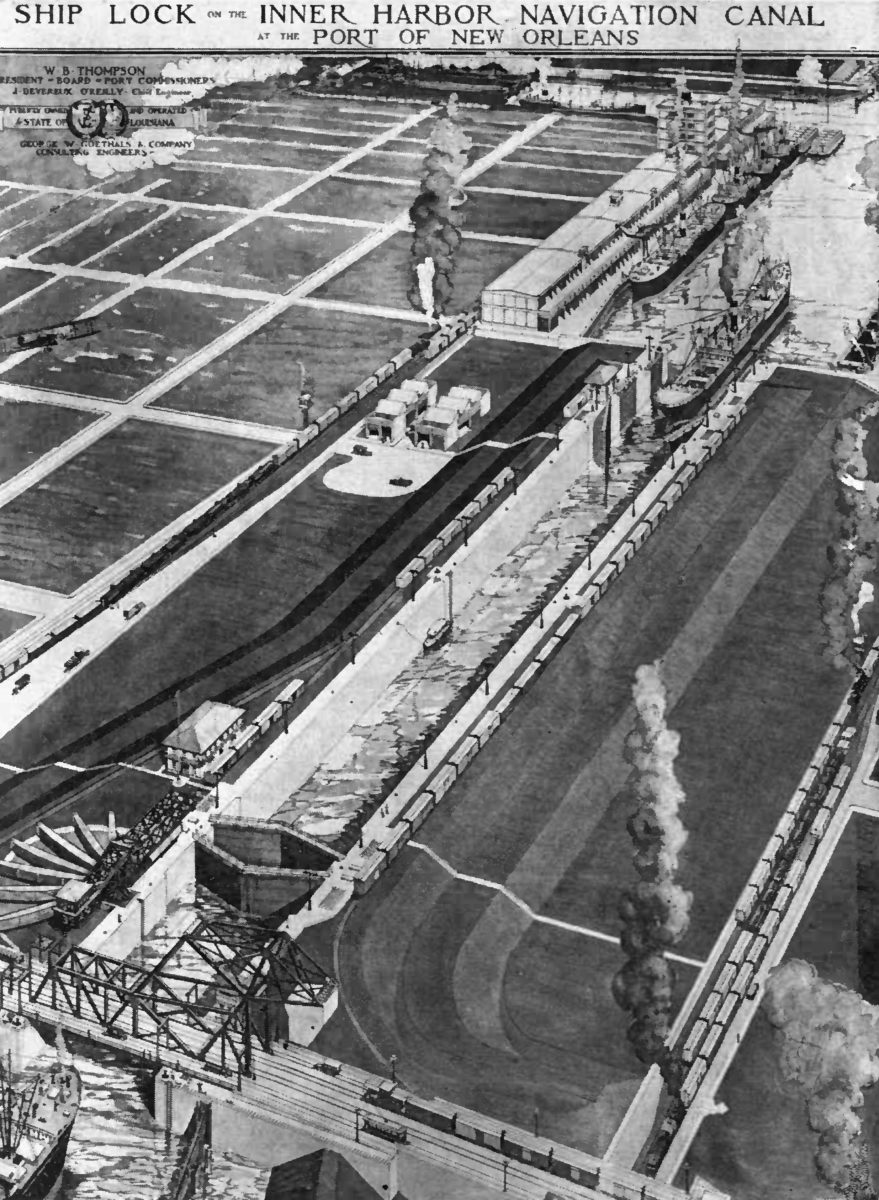

A 1921 drawing illustrating the IHNC Lock construction. Image source Team New Orleans, US Army Corps of Engineers, (CC BY 2.0)

In 1986, the Port sold its IHNC land and navigational lock to the Corp who intended to replace the historic lock with a new deep-draft version to service MRGO interests. While continuing to support the lock expansion, the Port saw problems with the tidewater system that the Port found troubling. The MRGO channel proved to be problematic and was underutilized and sometimes impassable because of collapsing earthen sides that were constantly eroded by ship wakes. The Corps spent a lot of time and money dredging the channel to keep the required depth of forty feet. The erosion significantly widened the channel over the years to over a quarter mile in some places. The Port was sensitive to the growing political fallout connected to MRGO environmental impacts as well the proposed expansion of the IHNC lock complex and its effects on the adjacent and neighborhoods. After Katrina, the Port removed their massive gantry cranes from the IHNC and moved back to the Riverfront. While still having barge industry ties in the IHNC, the Port of New Orleans is no longer a fiduciary partner and will invest no money in the Corps plan to expand the lock complex.

So, why now spend billions of dollars and thirteen years building a new lock into this residential neighborhood? A very good question with its answer’s roots in the Corps ownership of this land and its habit of putting the political influence of national energy and shipping interests above those of our citizens. For decades, the Corps of Engineers has been transforming the waterways and rivers of the nation for their clients: the barge and shipping industries. The Corps’ myopic view of water management projects seems blind to modern environmental science and the secondary and tertiary effects caused by its actions. The proposal to build a new lock in the Industrial Canal is a clear demonstration of the make-work mentality and unchecked entitlement that have contributed to the failure of the grand plan of the Industrial Canal. It should be understood that the COE is emboldened to act in such a way as it possesses “sovereign immunity” from accountability; the Corps is functionally above the law. As a branch of the military, the decision-making processes for these projects occurs largely out of public view. Of equal importance is the fact that this project does nothing to undo the years of poor water management decisions left behind by government and industry. This project squanders money that could otherwise be spent improving New Orleans flood defenses. Instead, building a new lock directs limited funding resources towards the needs of the navigation industry while ignoring the greater needs of the region, the City, and its residents.

Scope of Work

Aerial view of the Industrial Canal and Claiborne Avenue Bridge, looking south. The proposed lock is 5 blocks to the north of the Claiborne bridge (out of view). The left side of the image shows areas of modern home demolition. Photo by Michael Maples, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers/Public domain

In order to better understand the apparent disregard for the level of risk residents will be subject to as a result of the project, it is worth considering the location and aspects of its design in closer detail. The plan is to construct a new lock at Galvez Street, situated to the north of the Claiborne Bridge in the above image, so that fewer historic properties will have to be demolished. The original plan was to take three blocks of the Holy Cross-National Register Historic District, just southeast of the bridge, and construct a new lock adjacent to the existing one. This plan was eventually withdrawn by the COE due to community concerns: environmental impact issues and the loss of a significant number of historic buildings in the Holy Cross Historic district. The proposed Galvez Street location for the new lock will have the effect of bringing the Mississippi River water elevations 12 blocks further into the City; the River’s current water levels end at the St. Claude bridge. Twenty-four-foot-tall “T” walls will be erected from the River to that Galvez Street location. These walls will require over three years of pile driving adjacent to the Lower Bywater, Lower Ninth Ward and Holy Cross Neighborhoods; walls of similar design have failed and flooded these neighborhoods in the past

In order to create a chamber for the new lock, the Corps will excavate highly toxic sediment from the bottom of the Industrial Canal. There is no final solution for the destination of these excavations, but current planning scenarios have them loaded onto barges and then offloaded onto temporary sites in Orleans Parish until they can find a final resting place. One plan floated by the Corps is to use this material in the marshes to build wetlands. The documented presence of industrial wastes in these sediments do not meet federal regulations for this purpose and the Corps would be required to obtain a waiver from the Environmental Protection Agency to do this. All of this activity exposes the residents Orleans and St. Bernard Parishes to both air and water-borne toxins that will proliferate during more than a decade of proposed construction. No current environmental impact studies have been conducted to assess the effects of this project on area residents.

Once the new lock is complete and the twenty-four-foot-tall floodwalls have been completed, the Corps will then begin the immense task of demolishing the historic IHNC lock. Completed in the early 1920s, it was the single largest concrete structure in the City of New Orleans. With a mass of over 225,000 tons of concrete and reinforcing steel, the lock is roughly the size of the Chrysler Building lying on its side. This demolition will occur adjacent to the new floodwalls and their foundations; all resting in a very volatile geomorphology. The soil structure at the confluence of the IHNC and the Mississippi River is a roiling mixture of alluvial deposition and the hydrated sand remnants of an ancient seabed (Lake Pontchartrain). These conditions were well documented during the excavation of the IHNC and the construction of the lock required massive foundations beneath the lock chamber to ensure its stability. To date, the Corps has proposed no methodology for this undertaking or has it provided any data that this demolition will not undermine the new twenty-four foot walls that are intended to protect the city from flooding.

New Orleans Industrial Canal seen from the levee in the Lower 9th Ward, with a view of first lock, St. Claude, and Claiborne Avenue bridges. The blue towers of the Florida Avenue Bridge are visible in the distance. Image by Infrogmation, CC BY 2.5

A new bridge will replace the 1923 St. Claude Bridge; it will be a low-rise, twinleaf bascule type because of Historic District Landmark Commission concerns of impacts to the adjacent historic districts setting if a taller, mid-rise span type were built instead. Here, we are again confronted with the Corps’ apparent disregard for the project’s long-term impacts on those who cross the IHNC on their daily commute between St. Bernard Parish and New Orleans. There are two bridges that affect traffic over the IHNC: The St. Claude Bride and the Judge Seeber bridge at Claiborne Avenue. The Seeber Bridge can be raised and was designed for the Lake Pontchartrain water levels that are currently below it. Moving the lock to Galvez Street and bringing the higher Mississippi River water elevations below it will cause the Seeber Bridge to be raised more frequently than currently in order to allow barge traffic to pass. In addition, because of the new lock’s ability to handle more than double the volume of barges and tugs as the historic complex, the duration of these openings will be increased by over forty percent (COE data). This means that both the St. Claude and Seeber bridges will be up simultaneously and for longer periods of time. The result of this thirteen-year Corps project will bring commuting to a standstill and will impact hurricane evacuation procedures from St. Bernard Parish.

If you are a resident of the Lower Ninth Ward, Holy Cross or Bywater Historic Districts, the Corps is asking you to endure a minimum 13-year construction project in your backyard. As mentioned, there will be three to four years of pile driving and endless heavy equipment traffic; all adjacent to modest, shallow foundation homes and businesses. These neighborhoods have struggled to shore up residential and commercial re-development after the devastation of Hurricane Katrina. The proposed COE project will do nothing but stall, slow, or eliminate any progress that has been made to date. When the project is finished, there will be no direct benefits to the surrounding neighborhoods but rather, significant direct and unmitigated impacts resulting from the physical requirements of this heavy-handed project and the traffic and congestion issues that will result upon its completion.

Conclusion

New Orleans is one of the most endangered cities in America. Being surrounded by water, it is the home of the most intense Corps district. The Corps is broadly involved in almost every aspect of life with water and is staffed by a good many men and women who are exemplary citizens and long-term area residents. However, the Corps as a whole is a top-heavy, chain-of-command organization that is beholden to its clients. It has refused to factor into the lock project climate change, rising Mississippi River levels, the lessons of hurricanes Betsy and Katrina, or the possibility of actually abandoning this failed dream of the Industrial Canal. Instead, this project is mired in bad ideas hatched early in the 1900s, now at a time when the region and City are struggling to meet the challenges of the twenty-first century. These challenges call for more sustainable practices and projects that may be in conflict with Corps ideals. The hand of human intervention is all over our river, shipping channels and wetlands; connecting the river to the lake seems like a dangerous idea, opposition to which was most likely drowned out by the drumbeat of progress in the early twentieth century. The time has passed for high-risk channels with increasingly volatile barge traffic to be engineered into the middle of residential neighborhoods still recovering from the impacts of the last very high water. Indeed, what is evident here with the proposed Industrial Canal Lock expansion is the wish to continue the history of monumental authority used commercially to the detriment of the environment and people of our region. So, the problem for us now is to decide which century we must inhabit fully and in every respect for our City to survive the rising tide of planetary change.