Data Flows

Post-Natural Histories of Maize and Their Companions Along the Mississippi River

Sociologist Tahani Nadim introduces a collaborative exercise in experimental, ethnographic story-writing. Drawing on art, literature, and filmmaking, this research is focused on maize—the cyclical and seasonal lives of which, Nadim argues, configure socio-technical intimacies that cut across different times, both deep and human.

“What stands out are the ways we can trace the past to the present and the present to the past through geography. The historical constitution of the lands of no one can, at least in part, be linked to the present and normalized spaces of the racial other; with this the geographies of the racial other are emptied out of life precisely because the historical constitution of these geographies has cast them as the lands of no one. So in our present moment, some live in the unlivable, and to live in the unlivable condemns the geographies of marginalized to death over and over again. Life, then, is extracted from particular regions, transforming some places into inhuman rather than human geographies.”

—Katherine McKittrick, Plantation Futures

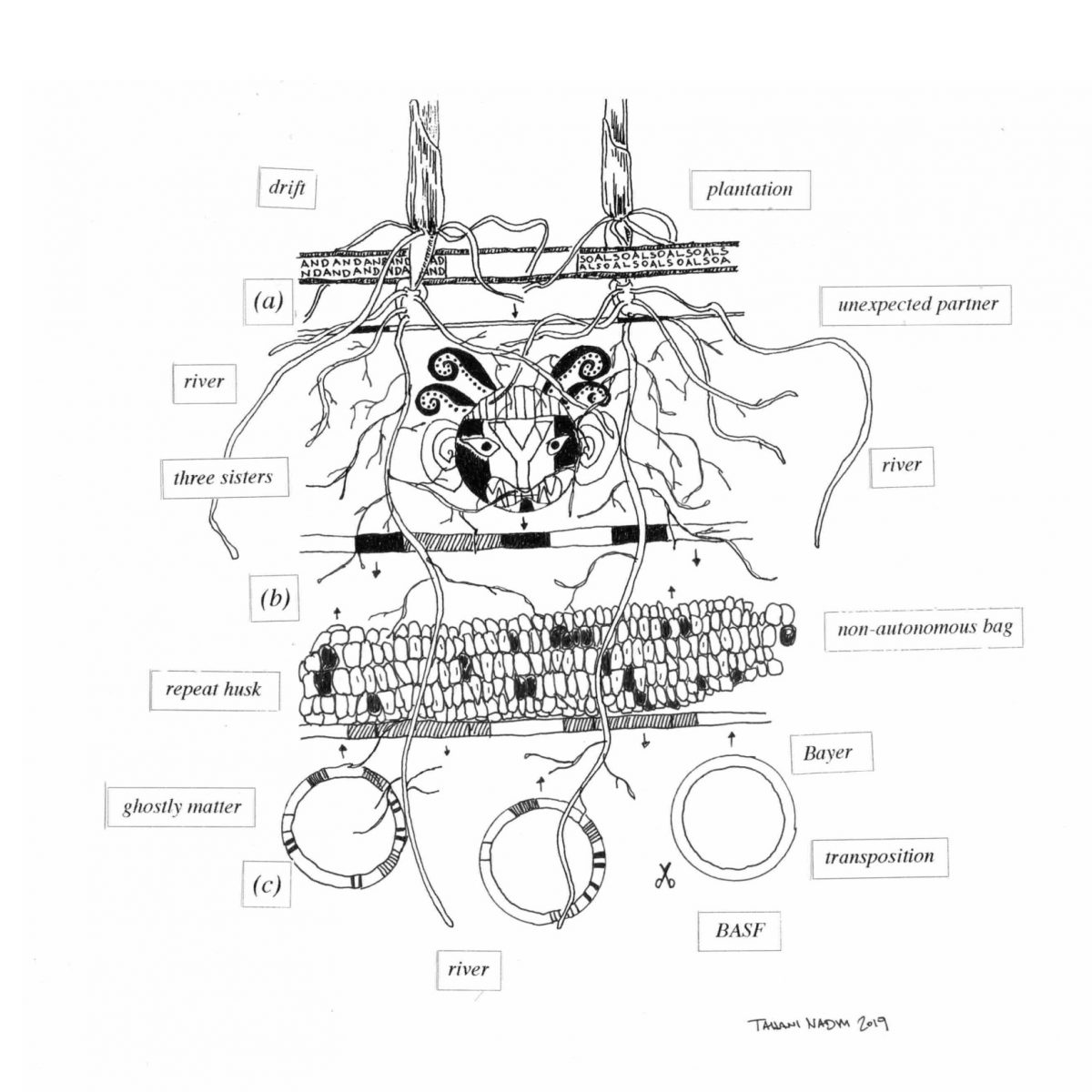

What can the archives of natural history tell us about genetically modified crops? How does a river divulge the geographies of marginalized? What might the rust on a combiner reel off about women’s health care? How do you read the biome through agrilogistics and vice versa? In other words, what stories contain the Anthropocene? By taking part in Mississippi. An Anthropocene River, I want to weave an experimental essay capacious enough for carrying multiple plots, plans, and plants. Put succinctly, I want to engage in what Donna Haraway, after Ursula Le Guin, calls “bag-lady story telling” that puts “unexpected partners and irreducible details into a frayed, porous carrier bag.”1 Concretely, I’m interested in maize (Zea mays) as a central model organism for the development of genomics and epigenetics, or epigenomics, and as a premier commodity crop. These figurations of maize are related. They have been radically reconfiguring human-environmental relations while mobilizing vast data machines that are intensifying ongoing expropriations and introducing novel types of extraction and concentration. At the same time, the lives of maize are cyclical and seasonal, recursively configuring socio-technical intimacies that cut across different times, both deep and human. Maize is thus a valiant companion for striking up “noninnocent conversations”2 with people and nonhuman worlds past and present. Specifically, maize lets me loop relations, from the Mississippi, to the Spree, to the Danube, and back; from speculative futures, to the Columbian Exchange, and back.

With this project, I would like to disturb conventions of storytelling that preclude the recognition and restoration of interdependencies across people, landscapes, and times. This necessarily involves problematizing my storytelling position as a mostly whitish, privileged academic, schooled in disciplinary structures that have been complicit in racializing regimes. Concurrently, I want to undo attachments to unhealthy data cultures where only some practices and people are permitted to generate and circulate consequential data. Such exclusivity condemns much of human life, as well as its implications in ongoing devastations, to “non-existence.”

Querying these data cultures also entails a generative de- and reconstruction of dominant archives, like those of natural history collections. This project is situated at the intersection of science and technology studies, cultural anthropology, natural history, and speculative problem-making—drawing on art, literature, and filmmaking. It might best be described as a collaborative exercise in experimental, ethnographic story-writing. It consists of four coeval movements through which such stories become assembled: I want to start with repairing data. Along the course of the journey, I would like to record different data moments, ranging from conventional data points, such as temperature and duration, to idiosyncratic and composite data points, such as “level of discomfort” or “presences of ghostly matters.”3 I want to start with proxy biodiversity/biodiversity proxies. Along the journey, I would like to record traces that indicate biodiversity as well as biodiversity that indicates something else. I want to start with people. Along the journey, I would like to share stories, experiences, dreams, fears, and hopes. I want to start and end as a guest.