How did human activity alter the Mississippi Basin?

An energy-based perspective

Through the practice of agriculture, the chemical energy produced in the process of photosynthesis is effectively made available to human use. But how has the expansion of agricultural practices influenced “natural” biospheres? And how much of the photosynthetic energy generated in the Mississippi basin is diverted to human use and how much of it returns to “natural” ecosystems?

Human activity has substantially transformed the surface of the Mississippi Basin. Much of the prairie—the vast natural grasslands of the central United States, once populated with buffalo—has been converted into agricultural croplands in the last 200 years. This conversion resulted in the emergence of different plant species, affecting when and how solar radiation was absorbed and how much water evaporated from the Earth’s surface into the atmosphere. Where croplands are concerned, humans harvest most of the land’s productivity, thus removing much of the chemical energy from the surface and bringing it into human use. These changes in land use have altered the overall functioning of the Mississippi Basin.

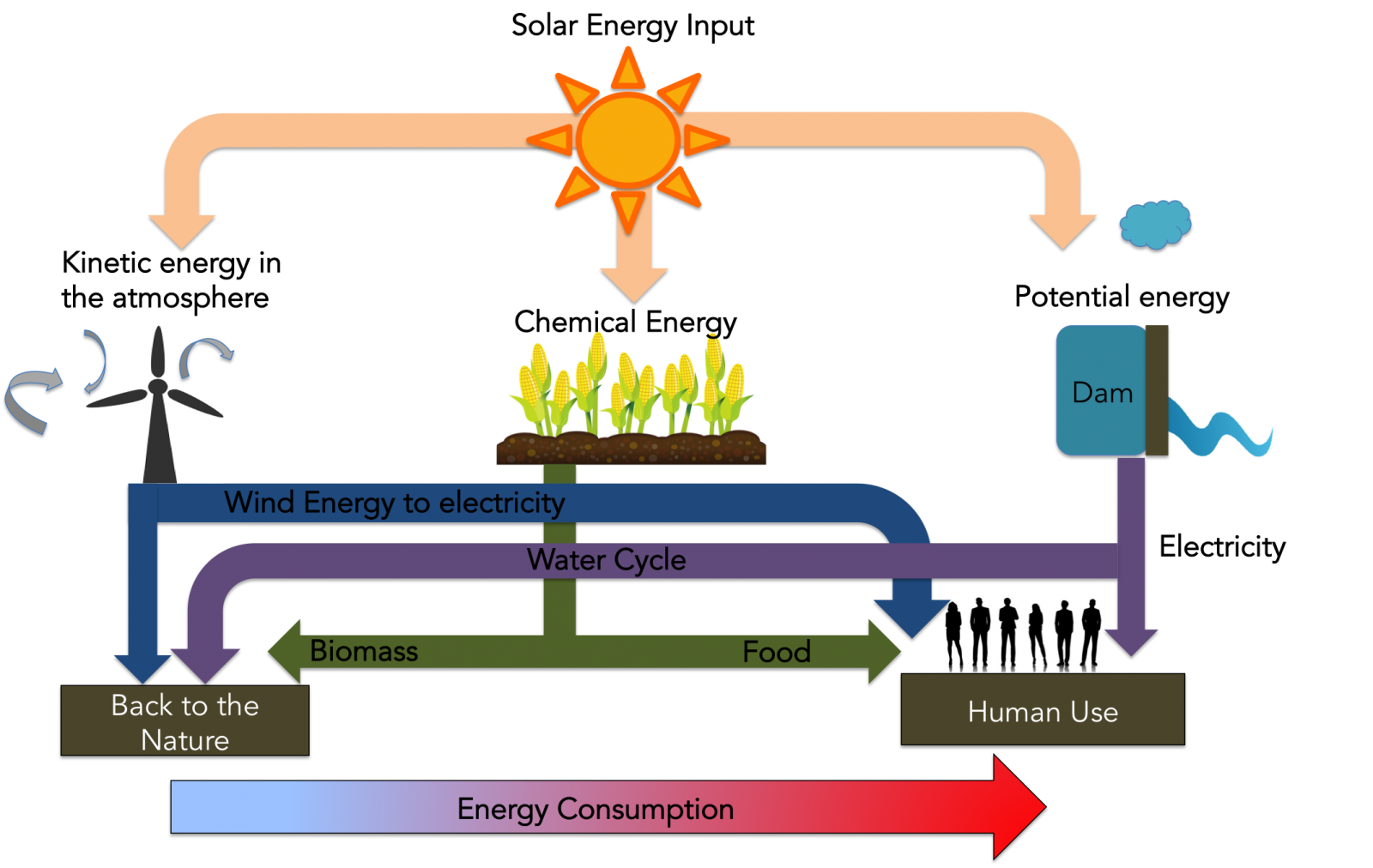

The goal of this project is to identify and quantify human-diverted energy conversions within the Mississippi Basin. The basic picture is that sunlight adds energy to the basin, and natural processes convert this energy into different forms. Absorption results in surface heating, producing thermal energy. The heating of the ground causes updrafts, creating wind. When water is available, surface heat converts some of that energy into water evaporation. Updrafts carry this moisture into the atmosphere, where it eventually becomes rain, generating the potential energy associated with precipitated surface water. Some of the energy is absorbed by plants, which use it for photosynthesis, converting it into carbohydrates. The rates by which these forms of energy are generated are typically small, representing only a tiny fraction of the Sun’s total energy input. Yet these processes play a vital role in basin dynamics. Winds mix air, water feeds plants and transports river sediments, and photosynthesis feeds natural ecosystems.

When humans settled in the Mississippi Basin, they increasingly altered the land’s surface by converting it into range and croplands. The major aim of this was to divert photosynthetic energy conversions and make them available for human use. Agriculture means that humans harvested the embedded chemical energy of crops as a food source. This energy is then no longer available to feed natural ecosystems or soil biota. Consequently, the natural biosphere has shrunk as human land uses have expanded and agriculture has intensified. The use of kinetic energy by wind turbines or potential energy by hydroelectric dams does essentially the same thing: diverting a natural energy source to human use, thus reducing the activity of the natural processes that depend on these energy sources.

In this project, we aim to put numbers to the energy diversions in the Mississippi Basin and assess how they have likely changed over time. We plan to use spatial data sets of climatological variables, such as solar radiation, winds, and precipitation, in combination with land-cover maps to estimate two energy-conversion scenarios. The first scenario will consider a hypothetical natural state where no energy conversions are diverted to human use. Using this scenario as a reference, we will then reevaluate these conversions for present-day conditions using land-use statistics as well as statistics on wind energy and hydropower. This comparison should tell us the extent to which humans have diverted natural energy conversions. From this comparison, we should also be able to identify how much more energy could potentially be diverted for human use.

We suspect that, particularly with regard to chemical energy generated by photosynthesis, most of the basin’s energy has been put to human use. This, in turn, would illustrate that the Mississippi Basin is indeed an Anthropocene river basin, one in which energy no longer flows naturally, but is predominantly used for human ends.