Defining a New Earth Epoch

Putting the Anthropocene on the Chronostratigraphic Chart

The geological time scale is the product of centuries of careful study of Earth’s history. This text describes some of that research process and how it informs the designation of a new potential epoch: the Anthropocene. This is the job of the Anthropocene Working Group, an interdisciplinary research group who, since 2009, have been investigating human traces in the geological record.

Defining the Anthropocene by a point in a geological deposit is a small but significant step in understanding the evolution of our planet and our species. The history of Earth is recorded in layers of rock that allow geologists to read what conditions were like in the past. Breaking down the story of a constantly changing planet into understandable, defined time periods has been a common feature in the development of human thought and critical in the development of geological science. Geologists use differences (and similarities) in rocks and sediment sequences to infer environmental changes that occurred in the past.

There is no one location on Earth where the whole of geological history can be found. The conditions that enable preservation are highly variable and produce a record that is fragmented and complex. Stratigraphy is the methodological tool by which physical information of the past—blurred and distorted by time and space—is systematically recorded and put into order. Geological science, since its inception, has used stratigraphy to build a picture of our planet’s formation and development from crustal evidence. The search for the stratigraphic onset of the Anthropocene is a continuation of this process.

Vast timescales are critical to our understanding of the sequence of events and processes leading to the formation of strata and their variability over time and space. Beginning very soon after the planet formed, waves have washed onto beaches, rivers have dumped mud in deltas, wind and rain have eroded mountains, and volcanic dust has settled at great depths in remote reaches of the ocean. While such physical processes may be separated by thousands of kilometers and differ in nature due to the geological complexity of our planet, they are unified by time. Temporal connections allow scientists to correctly order physical stratigraphic associations, even after our restless planet has buried, uplifted, and scattered layers far from where they originally formed.

As the science of stratigraphy developed, geologists used changes in rock types and the fossil record to define major units of geological time; for example, in a certain cliff, trilobite fossils (which are from the early Cambrian, 521 million years ago) that appear in vertically oriented deep-sea mudstones occur only at the base, while dinosaur remains (from the Triassic period, around 250 million years ago) in terrestrial muds at a different tectonic orientation occur only in higher deposits, above the trilobites. Type sections of strata where such astonishing changes could be observed and named became reference locations against which changes elsewhere could be assessed. This process has continued through geologists refining known and new stratigraphic details using the increasingly advanced technology and analytical tools at their disposal. The development of absolute dating methods during the twentieth century has been critical, since they are far more accurate than the former methods, which relied on superposition and fossil occurrence.

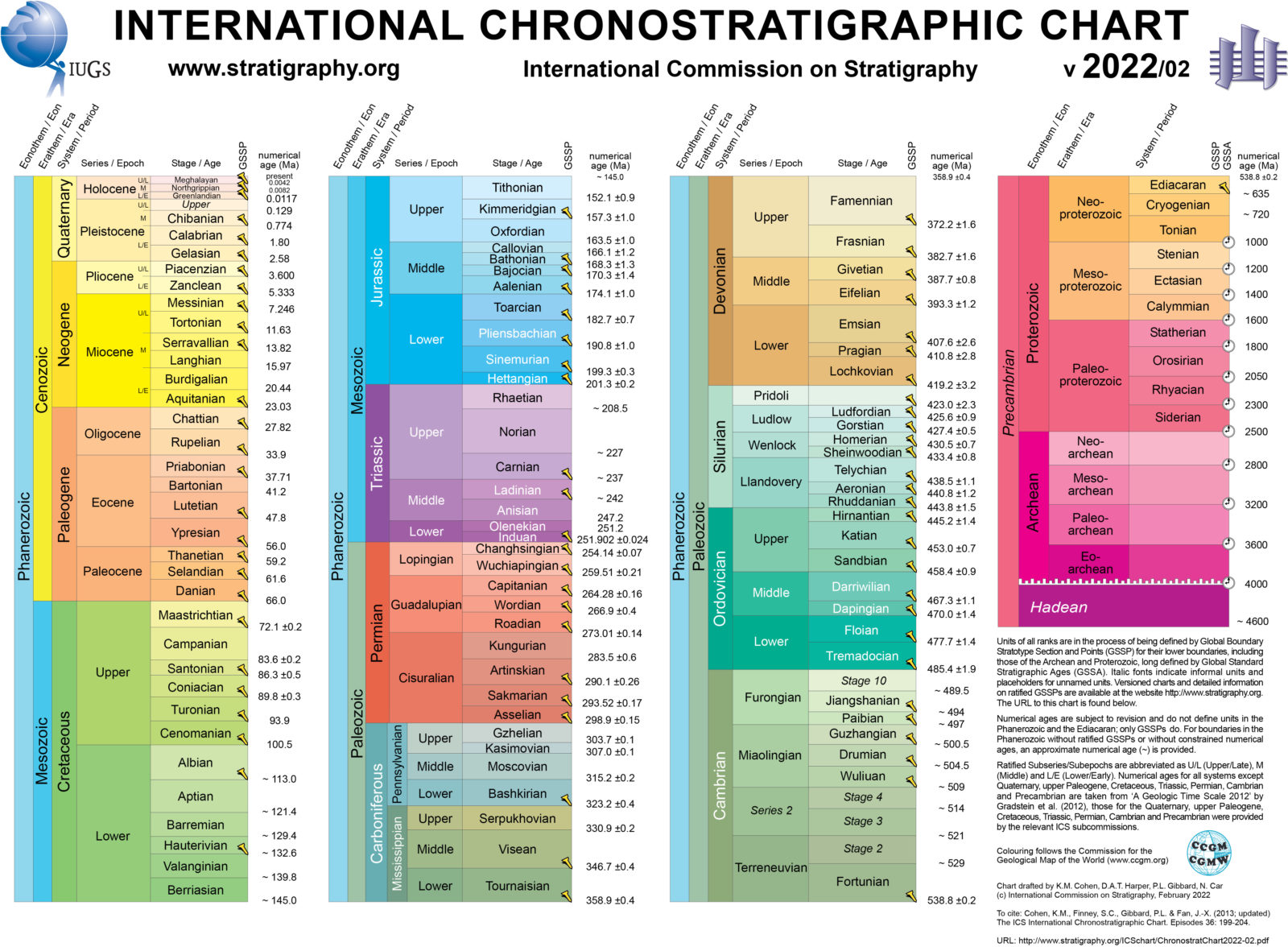

Centuries of geological research are represented by the International Chronostratigraphic Chart, produced by the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). This chart illustrates time boundaries and groupings of significant geological changes agreed upon by international teams of geologists. Since the 1970s, the ICS has worked toward defining the base of boundaries—that is, the starting point of new eras and epochs—by identifying Global Stratotype Section and Points (GSSPs), informally known as “golden spikes.” This process involves teams of scientists with in-depth knowledge of the relevant stratigraphy using empirical evidence to define a point in geological time at a specific location that can mark a boundary. The locations of GSSPs are not origin points: the Jurassic (201.3 ± 0.2 million years ago) did not begin in Tyrol, Austria and the Holocene (beginning 11,700 BCE) did not commence 1.5 kilometers below the Greenland ice cap. But the timings and evidence recorded at these locations provide reference sections of changes that are found across the globe.

The ICS divides its work between seventeen subcommissions, each comprising a committee of geologists who focus their attention on defining and researching specific periods of geological time. The Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (SQS) is tasked with defining geological time within the Quaternary period—the last 2.58 million years—which is formed of the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs.

The notion of the Anthropocene as a new unit of geological time in which human beings have significantly altered the planet was famously put forward by atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen in 2000, and the idea has since gained traction across a variety of academic fields and beyond. But the Anthropocene has not (yet) been ratified by the ICS.

The Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) was established and tasked by the SQS in 2009 to examine the Anthropocene as a chronostratigraphic unit, following its growing usage in the Earth system science community and preliminary analysis by the Stratigraphy Commission of the Geological Society of London. The proposed definition of a stratigraphic Anthropocene signifies that human activity has become a global geological force that has altered planetary conditions to such an extent that we no longer live in the Holocene. The AWG proposes that this transition has occurred in the mid-twentieth century, with unprecedented changes to planetary systems created by industrialization, technology advancement, and globalization.

Since 2019, the AWG has examined twelve sites across the planet as possible locations for the Anthropocene GSSP. These sites include a variety of environments with unique geological characteristics and deposition types, but all record high-resolution archives of human impacts over at least the last century. For an extensive description of the twelve sites in question, please see the individual guides to each site.

In 2022, we are at a critical moment in the process of defining the Anthropocene. In May 2022, the AWG researchers present the result of their analysis at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin. In the following months, the AWG will jointly assess the findings and identify the site most suitable for further evaluation by the SQS and eventually potential ratification by the ICS. A final decision on whether the Anthropocene will be incorporated into the International Chronostratigraphic Chart is expected in the next two to three years.

A Chronology of Anthropocene Working Group Key Events

2000

- In response to discussion of recent Holocene global change at a meeting in Mexico, Paul Crutzen improvises the term “Anthropocene”, then publishes it in an article in the International Geosphere–Biosphere Programme Newsletter, and two years later in Nature.

2006

- The Stratigraphy Commission of the Geological Society of London begins preliminary analysis in response to the growing visibility of the Anthropocene concept, largely in publications of the Earth System Science community.

2008

- Twenty-one (of twenty-two) members of the Stratigraphy Commission were co-authors of a paper that suggested a stratigraphic case might exist for the Anthropocene and that it should be investigated further as a potential new unit of the International Chronostratigraphic Chart.

2009

- The Anthropocene Working Group is established by the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy to “examine the status, hierarchical level and definition of the Anthropocene as a potential new formal division of the Geological Time Scale.”

2011

- Publication of The Anthropocene: a new epoch of geological time? by the Royal Society of London.

- Geological Society of London meeting on the Anthropocene (May 11)

2014

- The AWG have their first in-person meeting, hosted by HKW (October 16–18).

- A Stratigraphical Basis for the Anthropocene is published by the Geological Society of London.

2015

- The second AWG meeting is hosted by the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research at Cambridge University (November 24–25).

2016

- Members of the AWG vote informally to decide that the Anthropocene possesses geological reality, that it is best considered at epoch/series level, that it is best defined beginning in the mid-twentieth century with the ‘Great Acceleration’, that it should be defined by a GSSP.

- The third meeting of the AWG is held in Oslo (April 22–23), hosted by the Fridtjof Nansen Institute (FNI) and Research Council of Norway.

2018

- The fourth meeting of the AWG is held in Mainz (September 5–8), hosted by the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry.

- Funding is secured with the help of HKW to facilitate the examination of existing GSSP candidate sites and the collection and analysis of cores from additional sites.

2019

- The AWG hold a binding vote, to confirm that the Anthropocene should be treated as a formal chronostratigraphic unit defined by a GSSP, and that the primary guide for the base of the Anthropocene should be one of the stratigraphic signals around the mid-twentieth century.

- Publication of The Anthropocene as a Geological Time Unit by Cambridge University Press.

- The fifth meeting of the AWG is hosted by the New Orleans Center for the Gulf South (NOCGS), Tulane University (November 8–9).

2021

- The sixth meeting of the AWG is hosted at HKW and online (September 21).

2022

- The AWG voting process commences on October 3 with a prescribed interval of at least thirty days for discussion. The AWG begin voting on site selection and other decisions required of the GSSP in mid November. Further intervals of discussion and voting will continue into 2023.

- As a result of the initial AWG discussion period, three proposals have been decided upon being less favorable as GSSP candidate site (Ernesto Cave, San Francisco Estuary, and Karlsplatz), leaving the AWG with nine remaining sites on which to vote.

2023

- Each of the sites publish a paper within a special thematic issue of The Anthropocene Review, including an epilogue co-authored with the HKW and MPIWG project partners on the role of their collaboration in the research process. The site’s papers can be found at the bottom of each guide to the individual sites.

- The AWG announce the proposed GSSP candidate site in July 2023 at a meeting at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin.

2023–4

- The selected GSSP candidate will need to go through three further stages of voting; by the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy, the International Commission on Stratigraphy, and the International Union of Geological Sciences.

- If the GSSP candidate successfully passes these three voting stages, it will be officially ratified and gain a place on the International Chronostratigraphic Chart.