Archival Phase Shifts

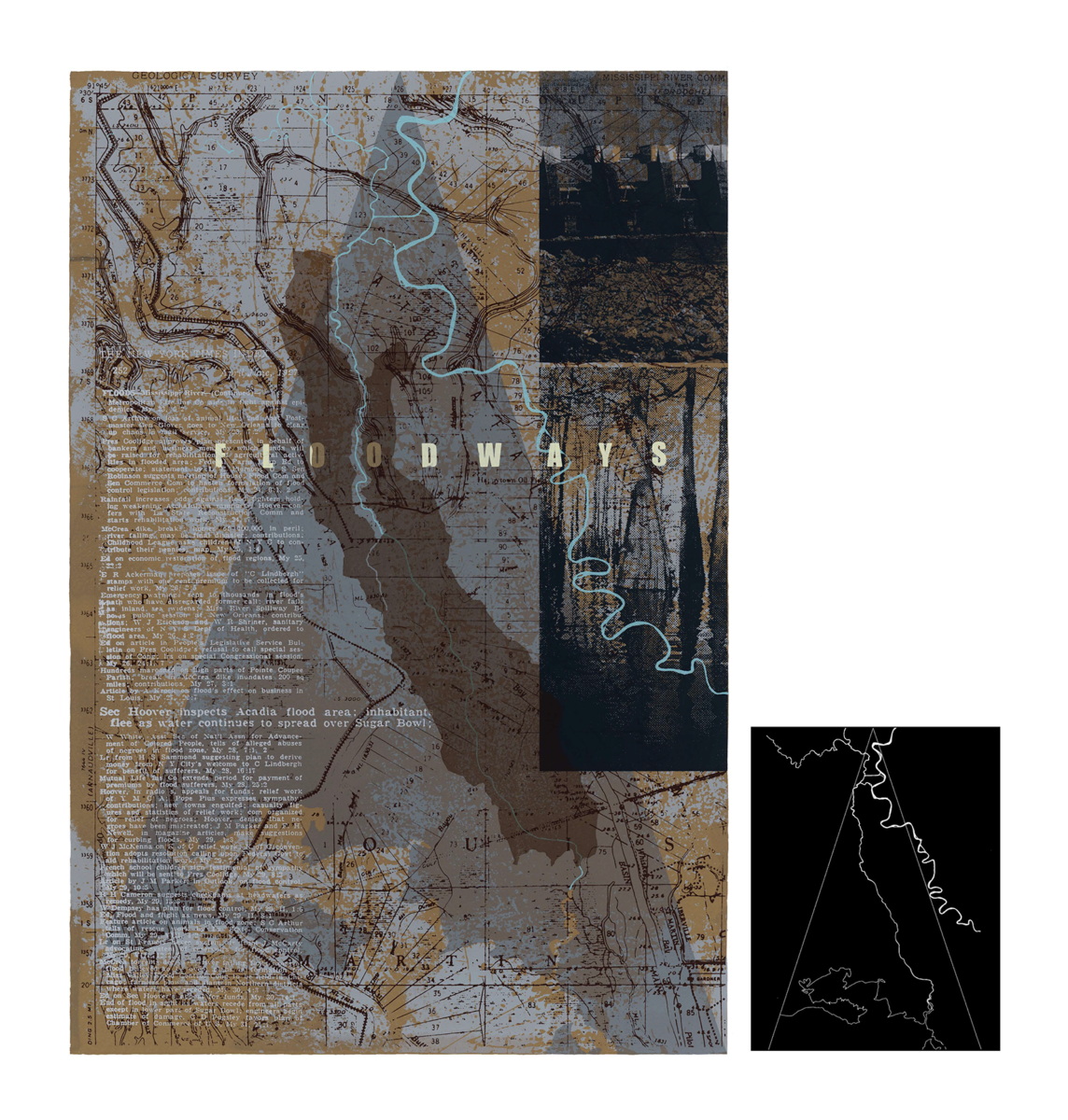

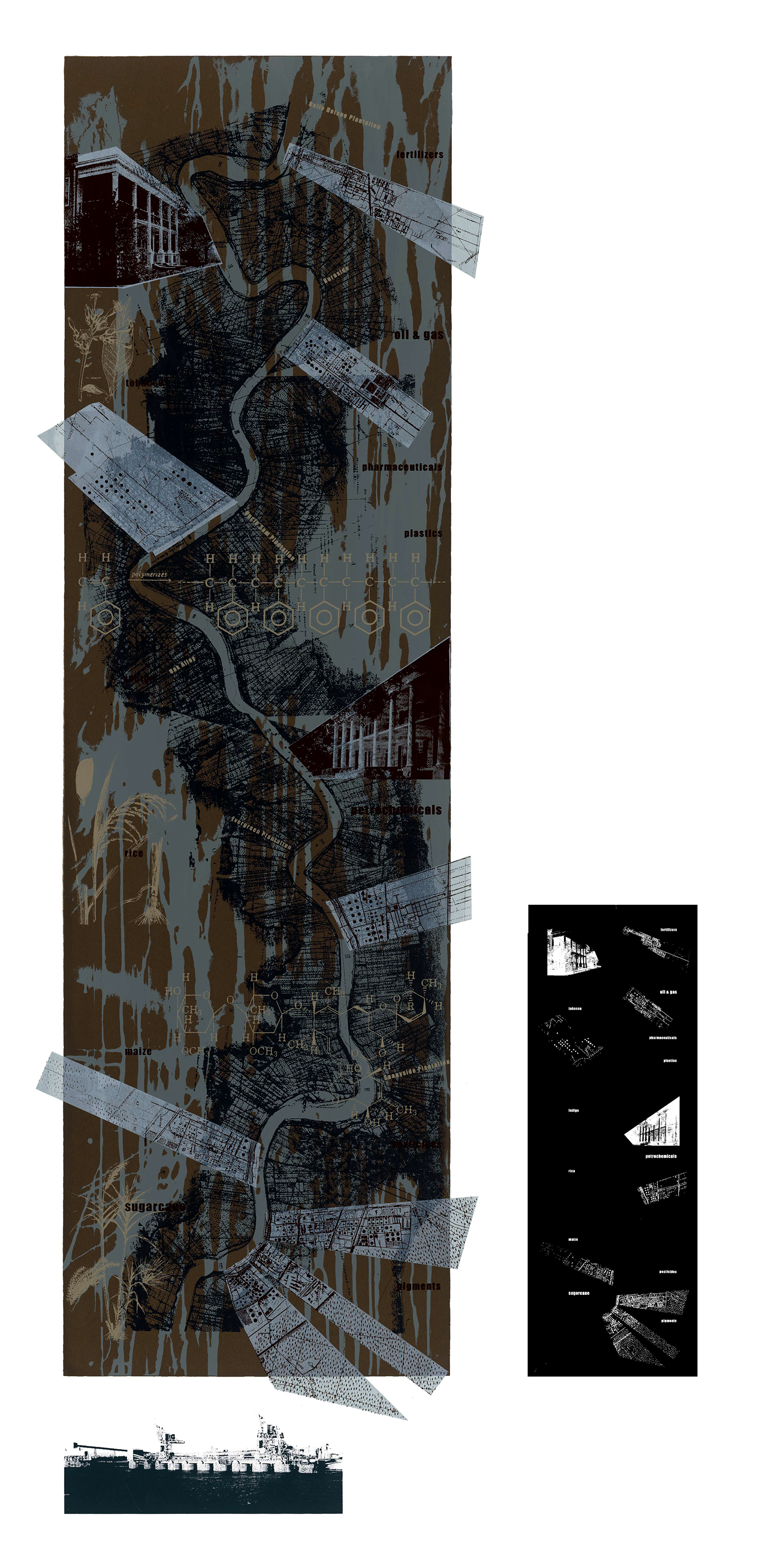

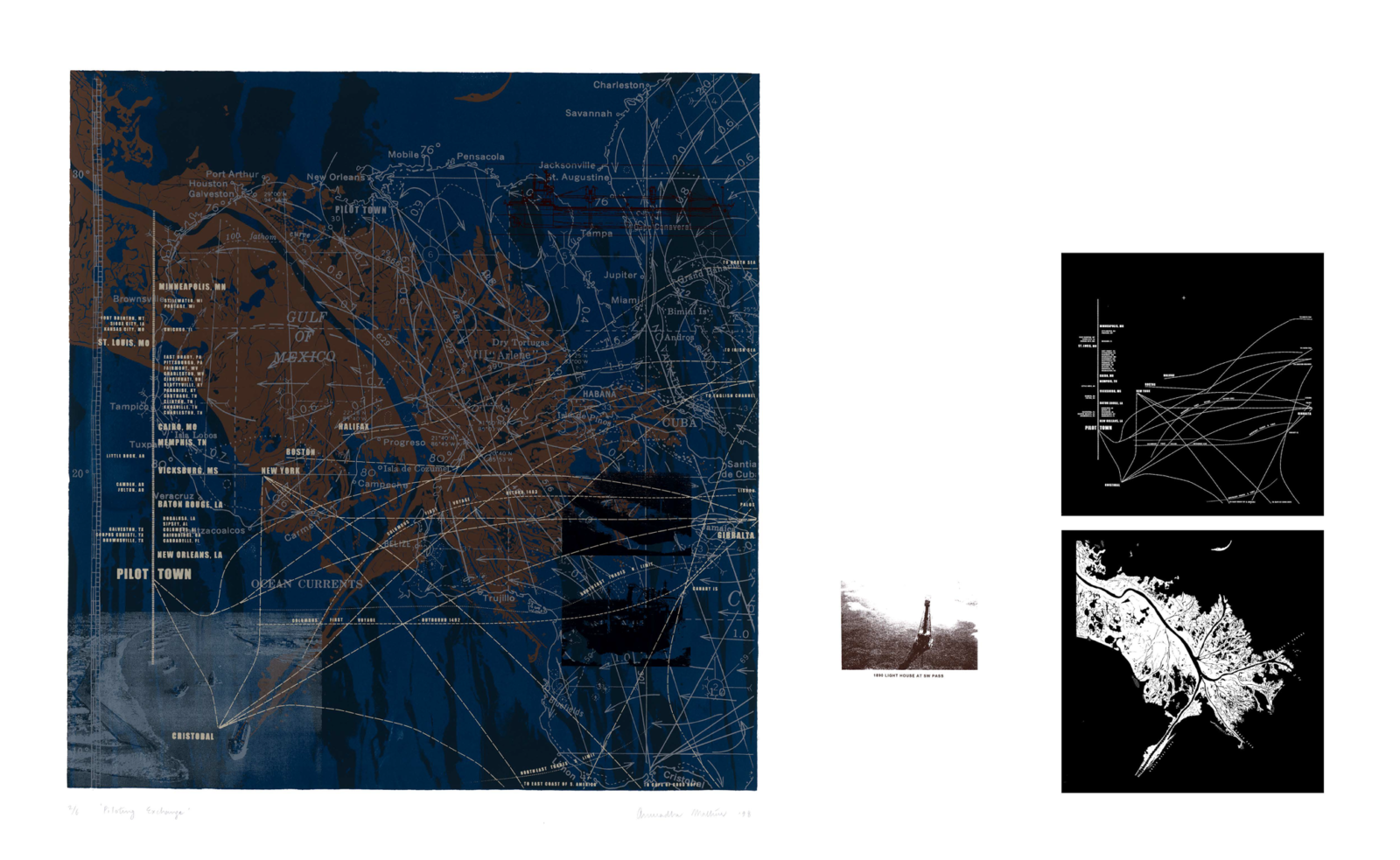

Archival records are historically defined by fixed content, structure, and context, but what might an “Anthropocene archive” look like? Alongside screen prints from the Mississippi Floods project by landscape architects Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha, which formulate a visual representation of the shifting landscape of the Mississippi River, media anthropologist Shannon Mattern proposes that—just as the archive of the Anthropocene Curriculum is documenting a messy, collaborative process of discovery—an Anthropocene archive would benefit from regarding itself as a “living” collection, one that captures the lives and deaths of the myriad entities transformed by the planet’s own phase shifts.

As ice turns to water and land to sea, the archive of that transforming Anthropocene world is compelled to engage with its shifting materialities. Not only do phase transitions constitute archival subject matter, via maps and data sets documenting retreating coastlines and threatened species, but they’re also manifested in archival records themselves, particularly those composed of geological material and extracted from geological grounds.

The archival record has historically been defined by its fixed content, structure, and context.1 Fixity affirms consistency and authenticity. Yet the rise of digital media and dynamic documents has undermined the fixity of records’ structure and content. Climatic crisis is also expediting the degradation of archival forms, like manuscripts and films, both necessitating and complicating the continual cooling of data centers to store digital materials while simultaneously exacerbating the risks posed to archives and special collections housed within flood zones.2 Context—“the organizational, functional, and operational circumstances surrounding materials’ creation, receipt, storage, or use”—is shifting, too, particularly as cultural heritage organizations are reassessing their relationships to colonialism and white supremacy, institutions that also formed the historical geopolitical and economic contexts for climate change.3

Several events, courses, and projects within the Anthropocene Curriculum have grappled with this fluidity and mutability, these phase transitions and context shifts—transformations that began well before the rise of industrialization and pollution, and before archival records were preserved to document their encroachment. To engage with this deep context, photographer Jennifer Colten and artist and architect Jesse Vogler turn their attention from the written archive to the landscape.4 They describe how historical documentation of the Cahokia Mounds of the American Bottom, the Mississippi River floodplain in Southern Illinois, tends to describe those landforms as either natural geological formations, animal habitats, or the creations of an earlier wave of European or Asian settlers. The mounds’ early white interpreters simply couldn’t conceive of them as the creation of an Indigenous society that settled the area5 around 600 CE. Yet, when we change the context and look at the landscape itself as evidence, we see an assemblage of “artifacts that index a way of being” as well as a mode of geoengineering: the mound is the “originary architectural gesture,” a “transitional object” marking the shift from a small settlement to a “becoming-city.” A fixed geo-archival structure takes on archaeological “content.” Recognizing these structures as human constructs, rather than merely “natural” forms, situates them within the realm of cultural history and deepens the archival repertoire of the region’s Indigenous populations.6

It was also in the American Bottom, amid the Cahokia Mounds, where, in 1926, the chemical company Monsanto founded an eponymous company town, Monsanto Town, a free zone offering minimal regulation and taxation. By the 1960s, when the town became one of the world’s top producers of toxic polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), local officials thought it best to dissociate from the corporate parent and adopt a new name: Sauget.7 Monsanto has likewise since rebranded itself as an agro-biotech company, and, in 2018, when it was acquired by Bayer, retired its radioactive appellation. Yet the research of Colten and arts organizer Matthew Fluharty demonstrates that, despite these reinventions, the chemical legacy remains: archived in the local soils and waters and in residents’ bodies—and embedded in the archives.8 Archivists have policies for dealing with corporate and individual name changes, and map librarians have tools for tracking changing place-names. The Anthropocene and our broader social reckonings present new challenges for archival description: reclaiming whitewashed and greenwashed histories, documenting places eventually to be submerged and life forms soon extinct, and recognizing Indigenous presences long ago expunged from the map and marginalized communities silenced in the archive.

Riparian scholar Patrick Nunnally notes that upriver from the mounds in Illinois, in St. Paul, Minnesota, “Dakota names and people remain in this place; subsequent layers of settler, industrial inhabitation have not erased the people, although these later layers make it difficult to see through them to the palimpsest of meanings underneath.”9 What we need, he proposes, “is the language that enables us to see through the palimpsest, to describe the layers of the landscape’s history, and to understand the dynamics of how people made places, understood, and inhabited them over centuries.” Can our conventions of archival description and other knowledge artifacts help us see through to these layers below?

Yet there are some fundamental values differentiating settler-colonial and Indigenous ontologies and epistemologies, which make that translation difficult. Communications scholar Sarah Lewison highlights the principle of property—the capacity to own land and people and to regard both as “resources” for use—and the ways property has historically been marshaled to oppress and expel disenfranchised communities, through redlining, “urban renewal,” and other exploitative policies.10 The idea of land as property is foundational to settler colonialism, whose extractivist tendencies are in turn foundational for anthropogenic climate change. “In Louisiana,” Lewison writes, “nine million acres of mixed wetlands were auctioned off for less than a dollar an acre, snapped up for timber and oil. Every canal that has ever been dredged through the swamp for logging, pipelines, construction, and exploration persists like an open wound, one that increases vulnerability to storm surges, hurricanes, erosion, and salt inundation.” Anthropologist Nathan Jessee, who has studied the resettlement efforts of the Isle de Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, explains that the disappearance of land—a profound phase shift—can be traced back to policies like the Swamp Land Acts of 1849 and 1850, which allowed states to drain wetlands for agricultural use; these acts, Jessee told Lewison, were “central to Louisiana making property out of this ‘uninhabitable swampland’ and setting the stage for private property development and extractive industries to come in.”11

Property is also central to the Western archive. Provenance, a fundamental principle of archiving, “dictates that records of different origins … be kept separate to preserve their context.”12 As archivist and anthropologist Jarrett M. Drake asserts, provenance “thrives with the presence of a clear creator or ownership of records and with a hierarchical relationship between entities,” which reflect and reinforce “the bureaucratic and corporate needs of the Western colonial, capitalist, and imperialist regimes in which archivists have most adhered to the principle.”13 Provenance, Drake continues, “emerged as a concept in the West at a time when most people”—Indigenous people, Black people, women—“were structurally if not legally excluded from ownership; ownership of their own bodies, minds, labor, property, and records.” Drake proposes that newer digital media—which loosen the fixity of the record’s content and structure—productively “complicate conventional ideas of custody and property,” too, “by enabling and encouraging shared stewardship.”14 Such developments also create the potential for broader community participation, as we see with Treasure Shields Redmond’s River Memory oral history archive,15 which documents how residents of St. Louis and East St. Louis experience their growing alienation from the river that divides and connects them. Finally, wider access to digital technologies, Drake notes, also gives more people the opportunity to name themselves—or to refuse identification—in the archives.

Still, provenance is what determines the “official” identities of some communities. Lewison explains that the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe and the Isle de Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, while both recognized by the state of Louisiana, are in the process of applying for federal recognition.16 The process, which can take up to thirty years, requires proving the tribes’ identities through identity constructs and records—many in fixed forms—validated by the state: “They must compile detailed evidence of their membership, genealogies, treaties, language, and governance for each decade of the twentieth century. The application takes the form of a narrative drawn from maps, diaries, letters, oral histories, and other archival materials.” The tribes must prove who they are in order to be eligible for the colonizer’s services and grants—a pitifully partial restitution for what was taken from them long ago. For Black Americans, however, as Lewison laments, “there is no application for the restitution of property they were swindled out of or forced to relinquish, or for the countless hours of stolen labor that augmented the wealth of others.”

Lewison’s colleagues, grappling with the paradoxical volatility of “property”—a seemingly fixed construct that often leads to dispossession, particularly for already disenfranchised communities—sought to devise a conceptual “phase shift” that would promote decolonization. They ultimately proposed that “multiplying the subject” might allow for a reparative, collectivist means of thinking about land stewardship (and, we might add, archival stewardship). Such collectivism constitutes a method and an ethos. In her work on the intersections of racial and environmental injustices in post–Hurricane Katrina New Orleans, Shana M. griffin, who worked with Lewison’s group, addresses her own shifting and layered identities—as an independent researcher, a scholar aligned with particular disciplines (namely, sociology and geography), an artist, an abolitionist, a feminist, an activist, and a former resident of public housing in the city’s Tremé neighborhood—and how each of these positions constitutes an ethical context, a framework for establishing her accountability to the people and places she studies and serves.17 Questions of contextual accountability should productively inform our cultivation and stewardship of both land and archives.

The Anthropocene archive is characterized by a fluidity, rather than fixity, of content and structure and protocol. It’s fluid in form, too, and not only because of the prevalence of digital records and dynamic documents. If a mound of earth can constitute an archival artifact, so too can more fluid geographic forms. As geographer Thomas Turnbull argues, the river itself is an archive; it “evidenc[es] not just efforts to alter the Mississippi’s flow, but [also] the similarly shifting cultural and political dynamics that have accompanied such endeavors.”18 While one can “read” the riparian archive by filtering and radiocarbon dating the “array of fine matter, minerals, particles, clays, microbiota, and more novel sediments … suspended within its flow,” understanding the river as an ecology requires immersive fieldwork, riding with those flows. Turnbull recounts of his experience as a traveler on the Anthropocene River Journey in October 2019: “Our canoe rode atop not just layers of water travelling at different velocities but also a thick repository of interactions between Earth and human history which, all the while, the river was busily archiving.” That fluid archive documents “interaction[s] between physical laws, ecology, and human interventions.”

The Mississippi is a living, breathing terrain. The Anthropocene archive it holds is fluid, not fixed, and documents “interaction[s] between physical laws, ecology, and human interventions.” Flows—Spreading Waters (1998) by Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha, shown alongside layers from the printmaking process. Part of the Mississippi Floods series. © all rights reserved

Sociologist Tahani Nadim, meanwhile, follows different regional flows: those of corn and data in industrialized, technologized agriculture—the kind of farming that Monsanto helped to cultivate throughout the Mississippi region and around the world.19 She writes: “Diffracting maize through data can render visible how variant forms of maize, like patented hybrids, are structured through heterogeneous networks involving copyright and patent laws, international development policies, population statistics, and logistical standards.” This vast archive of agricultural data—much of it focused on provenance—tends to perpetuate capitalist and colonial systems.20 Nadim continues:

The movement of crops, from farms to silos, barges, and processing plants to plates and troughs is nowadays accompanied by a thick data flow that is feeding more and more distributaries. Farm machinery is equipped with sensors that continuously send soil, land, and weather data and numbers on fertilizer use and water levels. These data can be aggregated to set crop prices or predict insurance claims or develop fertilizer. They can also be combined with data on land registration and credit use to drive the dispossession and privatization of common lands.

We can contrast this meticulously data-driven agricultural archive with the cultural practice- and process-based archaeological archive that food systems planner Lynn Peemoeller and her anthropologist, archaeologist, cultural heritage, and culinary colleagues discussed in a workshop at the Cahokia Mounds site in September 2019.21 They examined, through Indigenous ethical and epistemological frameworks, cultural histories of selective breeding and foraging, and how we might regard the “history of civilization as a history of seeds.”

What does it mean to “phase shift” from textual and audiovisual records to rivers and seeds, to incorporate riparian and carpological collections into the Anthropocene archive? For centuries, scientists have regarded Earth itself as an “archive”—and, as I described in the 2017 article “The Big Data of Ice, Rocks, Soils, and Sediments,” collections of these geological materials are critical for climate science.22 While many archivists have justifiably lamented the widespread metaphorical use of the term “archive” among humanities and social science scholars and artists, as well as their lack of engagement with archival studies and library and information studies scholarship, many cultural knowledge professionals have also embraced more capacious conceptions of archival records.23 Indigenous archive scholar Shannon Faulkhead suggests that a record “can be a document, an individual’s memory, an image, or a recording. It can also be an actual person, a community, or the land itself.”24 What distinguishes these various entities as archival, then, is the intervention of archival labor in the creation, collection, preservation, interpretation, presentation, and perhaps even destruction of their records.25

What might distinguish the Anthropocene archive is a critical reflection on the historical forces—climatic, geophysical, socioeconomic, and so forth—that have given rise not only to a transformed Earth but also to the archive documenting its condition. What phase shifts have brought these settler-Indigenous treaties and oral histories, sediment and water samples, seed and rock collections into the archive? In a 2020 article, entitled “Glimmer: Refracting Rock,” I examine how the illumination of rock samples not only transforms rocks into data, but also has the potential to “blacklight” the colonial histories of extraction and collection that undergird many natural history collections.26 What archival practices, from creation and collection to description and preservation, might Anthropocene archivists deploy to ensure that the records and geological specimens in their collections speak to the shifting structures and contexts that engendered their very existence—the mining operations and government agencies and community workshops and chilled storage facilities that have generated and sustained them—and that also render them essential for understanding a rapidly transforming planet? Just as the archive of the Anthropocene Curriculum is documenting a messy, collaborative process of discovery, an Anthropocene Archive would benefit from embracing and acknowledging shifts in its content, structure, and context; incorporating situated and Indigenous and more-than-human knowledges that aren’t always commensurate with one another; and regarding itself as a “living” collection—one that captures the lives and deaths of the myriad entities transformed by the planet’s own phase shifts.27 Shifts manifested in flash floods and slow violences, in redlined maps and climate models, in wilting leaves, melting icebergs, and seeds that store the history of civilizations.