Landscapes of Confluence

The landscapes of the Confluence territory exemplify the impacts of history and agricultural practices. Brian Holmes takes us on a tour through the region, drawing attention to different approaches to land cultivation.

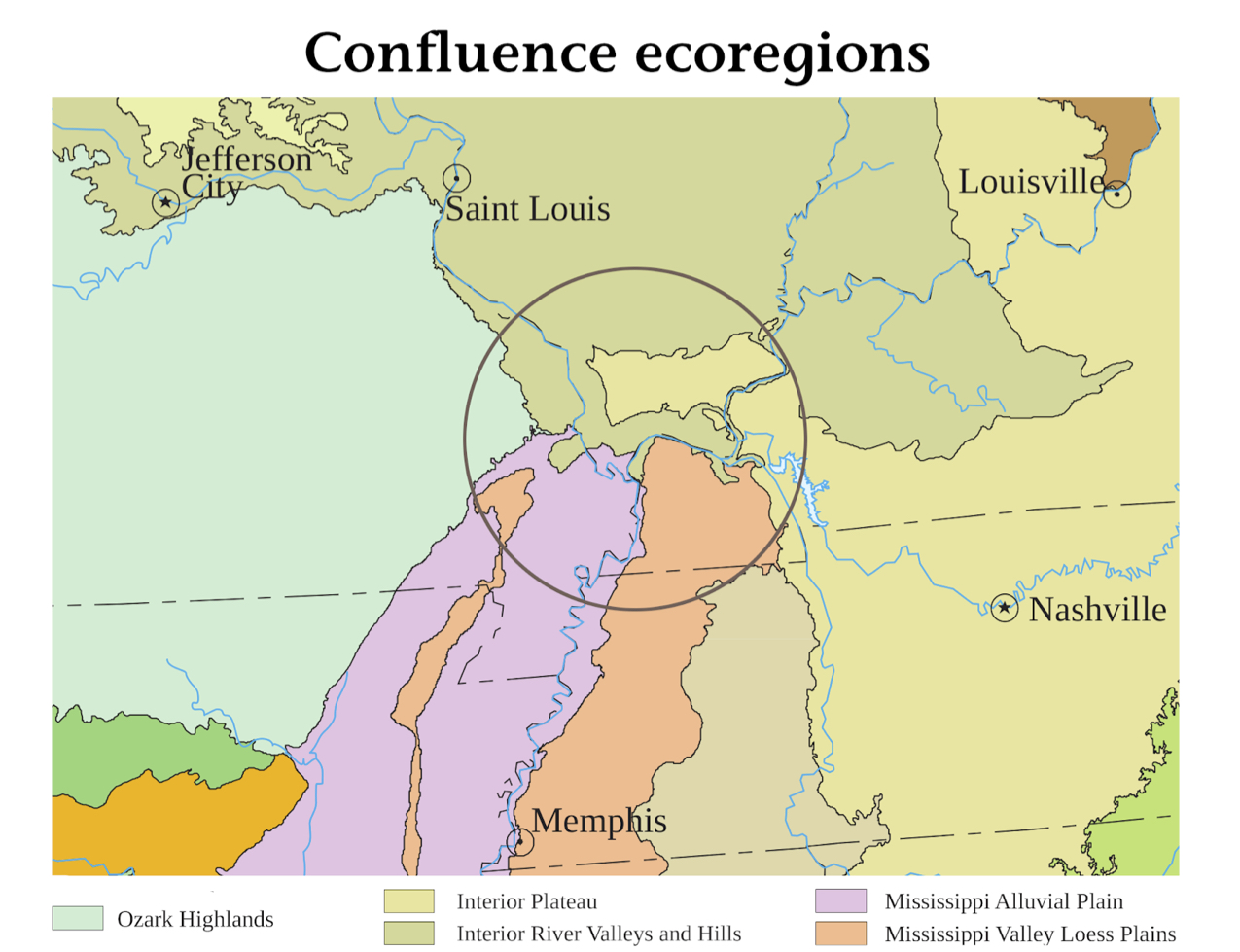

Confluence Ecologies (Field Station 4) takes its name from the meeting of two great rivers, the Mississippi and the Ohio. But it also refers to the multiple ecoregions that overlap and intertwine in Southern Illinois. The Ozark Highlands border us to the west. The Interior Plateau comes on with thick oak-hickory forests from the east. The glacially sculpted River Valleys and Hills to the north are dominated by corn and soybeans, with trees across the highlands and coal beneath the fields. To the southwest, a vast Alluvial Plain marks the outline of the sixty-million-year-old Mississippi Embayment, which gradually filled up with sediment from the river and is best known today for its Mississippi Delta blues. Alongside it, the Loess Plains prolong the incredible fertility of the Delta soils. All this is the Confluence region. And a hyper-active human population changes it continually. Field Station 4 is about political ecology.

Our Sunday bus tour began with the Cache River Valley at the southern tip of Illinois, about an hour south of Carbondale. This was an ancient bed of the Ohio River, formed by glacial advances and melt episodes between eight and twenty-five thousand years ago. When Europeans first came it was a sunken pond-and-swamp complex, filled with bottomland hardwoods and a great variety of birds. Early settlers moved onward to farm the rich northern plains, but latecomers eventually lingered and began to drain the swamps in the early twentieth century. The idea of the bus tour was to look up close at these changes in the land.

Map of Cache River Valley in southern Illinois, including Bay Creek, Post Creek Cutoff, and breached Karnak Levee.

The Main Brothers dug a long ditch with lateral channels to float hardwood logs to their sawmill in Karnak. Large agricultural landowners pressed for more improvements, leading to the dredging of the Post Creek Cutoff, which reroutes most of the Cache River through an increasingly eroded gully down into the Ohio. In the 1950s a Diversion Channel was installed at the river’s end, to shift the remaining trickle of water from the Ohio to the Mississippi. And the big farms just kept on growing. Local resident Max Hutchison woke up in the late 1970s to realize that the forests and pools he loved were disappearing before his eyes, dried by ditches and swallowed by soybeans. Our first stop on the tour was the breathtakingly beautiful Heron Pond, saved along with an emerald string of cypress-tupelo environments by grassroots and government activists in the 1980’s and 90’s.

The journey continued south through rolling hills and river bottoms to the decaying town of Cairo, Illinois. It was a major river port up to the late 1960s, but local elites failed to accept Black people’s struggles for racial justice during the Civil Rights Movement. Still protected by impregnable floodwalls built by the Army Corps of Engineers, the once-proud city in ruins offers its own mute commentary on the political ecology of the present.

Our final destination was Fort Defiance State Park, site of the great river confluence. According to the historical markers at the entry to the park, Lewis and Clark stopped here for six days on their westward journey of discovery and conquest. But get this: The actual confluence in 1803 was somewhere way back around Second Street of present-day Cairo! The park that we visit today was slowly formed by sediments over a century’s time. So don’t believe everything you read. We came here to see two rivers meet, and to experience two performances. More on that here.