Faith, Family, Farming

Tracing the origins of the original “American Farmer” Johnny Appleseed via the various incarnation of the “Wild West” that have led to the era of Apple Inc. and the quantification and gridification of American landscapes, Jamie Allen for Temporary continent. unearths the role folklore has played—and continues to play—in harvesting worth of all kinds. Locating the phenomena in the Midwestern United States context of Field Station 2, this reflection also draws parallels between systems and processes that operate at a global scale.

A t-shirt for sale in the women’s section of the gift shop at the John Deere Pavilion, visited as part of Field Station 2’s traveling seminar entitled Extractive Infrastructures and Imaginaries. Photograph by Jamie Allen

Then God said, “Let the earth bring forth vegetation, seed-bearing plants and fruit trees, each bearing fruit with seed according to its kind.” And it was so.

— Genesis 1:11

There are few American folklores as powerful, or as powerfully abused, then that of the American Farmer. One such fable began with John Chapman, a real human being and 18th- and 19th-century nurseryman, propelled and propagated during and after his lifetime as the myth of “Johnny Appleseed.” Chapman was operative in precisely the Illinois state territories that we traverse through, during its season of massive, mostly grain, corn and soybean harvest, with Field Station 2: Anthropocene Drift. According to the mythological propagation, Johnny (a good, Christian Swedenborgian) travelled across America planting trees that would eventually allow American things to be called “as American as the apple pie.” He did so in a landscape that was, and often still is, supposed as empty and barren, unmarked, uncultivated, and unoccupied. This has, of course, never been the case, as the lands in which Chapman placed his apple nurseries were places in which people already lived on, worked with, and cultivated the soil. In this Midwestern United States, these people are part of numerous indigenous tribes, whom Chapman’s real activities and mythos played a part in displacing, deceiving and decimating.

Amongst those who have survived and thrived, despite these uninvited incursions, are people of the Ho-Chunk, whose lands were also visited as part of Field Station 2—Blackhawk Rock at Kickapoo Valley Reserve, among other locales, guided by Bill Quackenbush alongside other gracious hosts, to whom we, as visitors, remain grateful. It would be Bill’s generosity and trust—and against-all-odds and against-all-historical-lessons opening of lands and offering of cheerful friendship—that we hoped would set a tone for the groups of learners and listeners of the River Project. All of us find ourselves looking for waypoints and guidance to figure out where we are on our own journeys, down the Mississippi and otherwise, and to find direction through a turbulent process and program that calls for the examination of even the most personal, cultural, and geopolitical standing, stances, and practices.

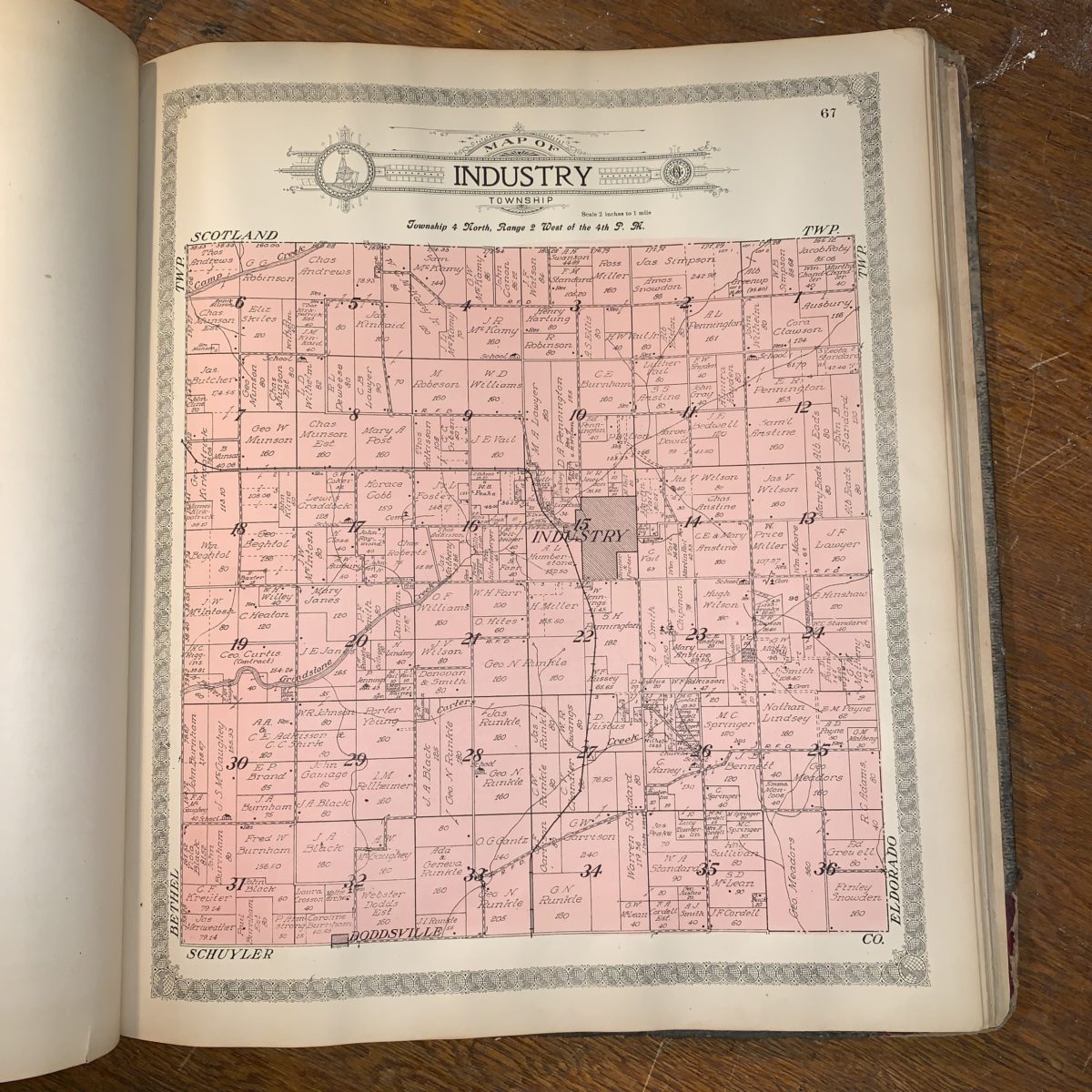

The apple, duly acknowledged by Michael Pollan and others for its evolutionary success and self-propagation through human cultivation, also plays its ambiguous role as an enabler of colonialism. It’s a kind of North American Jaffa orange, conscripting and then overwriting the geographic histories and territorial relations of peoples, in the name of particular kinds of productivity for particular kinds of producer-consumers. Appleseed’s “nurseries,” real and symbolic precursors to the quantification and gridification of American landscapes, the doling-out of its lands to white people, and its subsequent technological and industrial subjugation. Johnny Appleseed himself became a very rich man by selling his enclosed seedling apple tree plots, grown on land he did not pay for to arriving settlers at high margin, before moving on to “nurse” other unclaimed lands. Perhaps in homage to this originally American pirate-pioneer of disruptive innovation, the California company Apple Inc. continues to use the name “John Appleseed” as a fictive moniker, for corporate demos and tech development.

This kind of disruption, against the various straw men of “regulation” and “government intervention” that free marketeers in U.S. history are always anxious will fetter the “free” flow of capital, is also why the great drive west is still invoked to refer to emerging markets, as in, China as the “Wild West” of global investment. “Wild” refers to the precarious speed that opportunities became available before agreed upon practices and standards set in, to various “land grabs,” actual and otherwise, that “opportunize” the insecurity and contradictions inherent to “ownership” of lands, airs, waters, and information. This is an elastic tension and critical resonance between public, commons agreements and infrastructure (paid for by the government), and private investment (which is afforded and constrained by these agreements and infrastructure) in the U.S., which continues to reverberate through American popular political economics. These are projections that also allow for de facto environmental sacrifice zones in places like Monsanto, Illinois (now Sauget), where chemical industries took advantage of the “Wild West” of absent environmental regulation throughout the 20th century—and which Field Station 3 will take us to.

Robotic lawn mower demonstration in the back left corner of the John Deere Pavilion, 1400 River Drive Moline, Illinois. Photograph by Jamie Allen

On Saturday, September 29, the travelers of the Anthropocene River Project are among public visitors to the John Deere Pavilion, a kind of corporate experience, turned showroom, turned house of worship to the labor theory of property. While we are there, the dressed up high-schoolers of Moline taking part in homecoming, have their parents take coupled and group photographs on, inside, and in front of the farm machinery outside and within the pavilion. The place even seems to be laid out like a church—from an exterior courtyard strewn with sportier new models of green and yellow farm machines, visitors pass through a portal, to a vestibule reception. Two side aisles linearize and narrate histories and futures of not just the company but the future of global agriculture. A central, windowed nave culminates in an elevated altar where an awe-striking, massive combine machine sits beneath an arched dome.

Photograph by Jamie Allen

Photograph by Jamie Allen

We hear later this same day from Alyosha Goldstein on how Western agriculture is itself a technology that leaves “the land in pieces,” just as it is a central faith, supposed to hold America together. Goldstein’s lecture, provocatively and problematically, was delivered in a house John Deere’s son Charles built, now the Butterworth Center. The deep crimson velvet chairs and walls of the Butterworth give us easy-to-point-at examples of the often harder-to-see slower violence that paid for them—violence against land and river, and peoples like the youth of the Chi-Nations Youth Council whom we will meet the following day.

North American farmland continues to co-constitute global capitalist transformations, as the things we call “land” and “home” are conscripted as the origins of commodities, and as modes of capitalization that seems to know no bounds. Yet these lands, like the bible-thumping faiths of late colonial settlers that attempted to “settle” them, resist subsumption by narrative myths of productivity. Even so, Western, white culture still struggles to literally literalize faith, spirit, relation, and nature, as rational narrative and chapterized grids—how to fit the world into a book, a bible, a story, a script, a database, a ledger? These are the stories of Western capitalization that we continue to live through today, and that are sounded out in the past, present, and future visions of the John Deere Pavilion:

The Industry Township page in an early 19th-century land-title registry, seen at the Western Illinois Museum on the route between Field Station 2 and Field Station 3. Photograph by Jamie Allen

What we live on, own, and are attached to, so goes this Lockian narrative, must be harvested for all it is worth and more. Every individualized resource, is commanded and demanded to increasingly produce some form of monetary value, extracted as not wholly new forms of labor-ized homes, modes of transport, clothing, et cetera, ad nauseum. John Deere, among just a few others, are designing automated pacemakers for the arrhythmic beating heart of America’s “heartland,” and the rest of the world, leaving individual producers and laborers on the outside of a fenced-in corporate and technological fantasy—of hyper-productive, labor-less, and unpeopled lands—entirely legible, and giving up everything.