In Search of Lost Crops Where the Buffalo Roam

Archaeologist and ethnobotanist Natalie G. Mueller reflects upon how her experience of a very special meal, which took place under the auspices of Field Station 3, brought new resonance to her research questions concerning lost crops and the answers that were waiting to be discovered in some surprising places: namely, buffalo dung.

A transformative moment for my understanding of lost crops came during fall of 2019, when I shared a meal made from my harvests with a wonderful group of friends and colleagues during the Anthropocene River Journey. To my knowledge, this was the first time anyone had enjoyed these plants as food in over five centuries.

Chef Rob Connelly serving dishes made from lost crop seeds at the Granite City Arts District as part of the Anthropocene River Journey's Field Station 3 visit (left), and (right) one of the chef's creations, featuring erect knotweed seed crackers and squash mousse. Thanks to Rob Connelly and Lynn Peemoeller for making the Edible Narrative possible. Photo by Natalie G. Mueller.

One of the great unsolved mysteries about the origins of agriculture is why people chose to spend so much time and energy cultivating plants with tiny unappetizing seeds in a world full of juicy fruits, savory nuts, and plump roots and tubers. Many anthropologists believe that the only explanation is desperation: Either human populations grew too large to live on better foods, or environmental conditions rapidly changed and caused a decline in the plants and animals that humans preferred to eat. In either scenario, people turned to collecting the seeds of annual grasses and herbs because of scarcity—not because they were attractive foods.

My colleague Paul Patton collecting seed from scattered populations of goosefoot, a lost North American seed crop, in Ohio, 2017. Photo by Natalie G. Mueller

Anthropologists in this school of thought point out that collecting small seeds from scattered plants or fragmented populations is time consuming and yields low caloric returns compared to, for example, collecting nuts or tubers (edible roots). Worse, the costs in time and labor of eating small seeds do not end with the harvest: small seeds need to be threshed, winnowed, and, in most cases, cracked, ground, or sprouted in order to be turned into food that humans can digest. This is because most are encased in layers of tough, indigestible tissue that protects the food contained in the seed itself.

Before (left) and after (right) cleaning goosefoot seeds. In my experiments, this process takes about three times as long as harvesting. Photo by Natalie G. Mueller

Another strange dimension of contemporary agriculture is that many of the species people eventually domesticated would have been very difficult to cultivate in their wild form. This is because, again, of all those seed protections. Seed and fruit coats prevent moisture from reaching the seed and delay germination. If you collect the seeds of wild crop ancestors and then try to plant them the next spring without any kind of seed treatment, most will not germinate. How did ancient people overcome this barrier? We know they eventually went from simply collecting seeds from naturally occurring stands of wild plants to clearing fields and planting seeds. But why would they bother if the seeds they planted never germinated?

Germination of wild-type seeds with robust seed protections (left), and of domesticated-type seeds with weaker protections (right) after the same treatment. These seeds came from the lost crop erect knotweed, which was domesticated by ancient Indigenous communities in eastern North America. Photo by Natalie G. Mueller

I’m hoping to find the answer to both of these questions in… bison dung. Now, a pile of dung might seem like a strange place to look for answers about the origins of agriculture, but bear with me. In summer 2019, I published a paper with my colleague, Rob Spengler, arguing that grazing animals like bison may have played an important role in the domestication of many of our crops. What follows is that story.

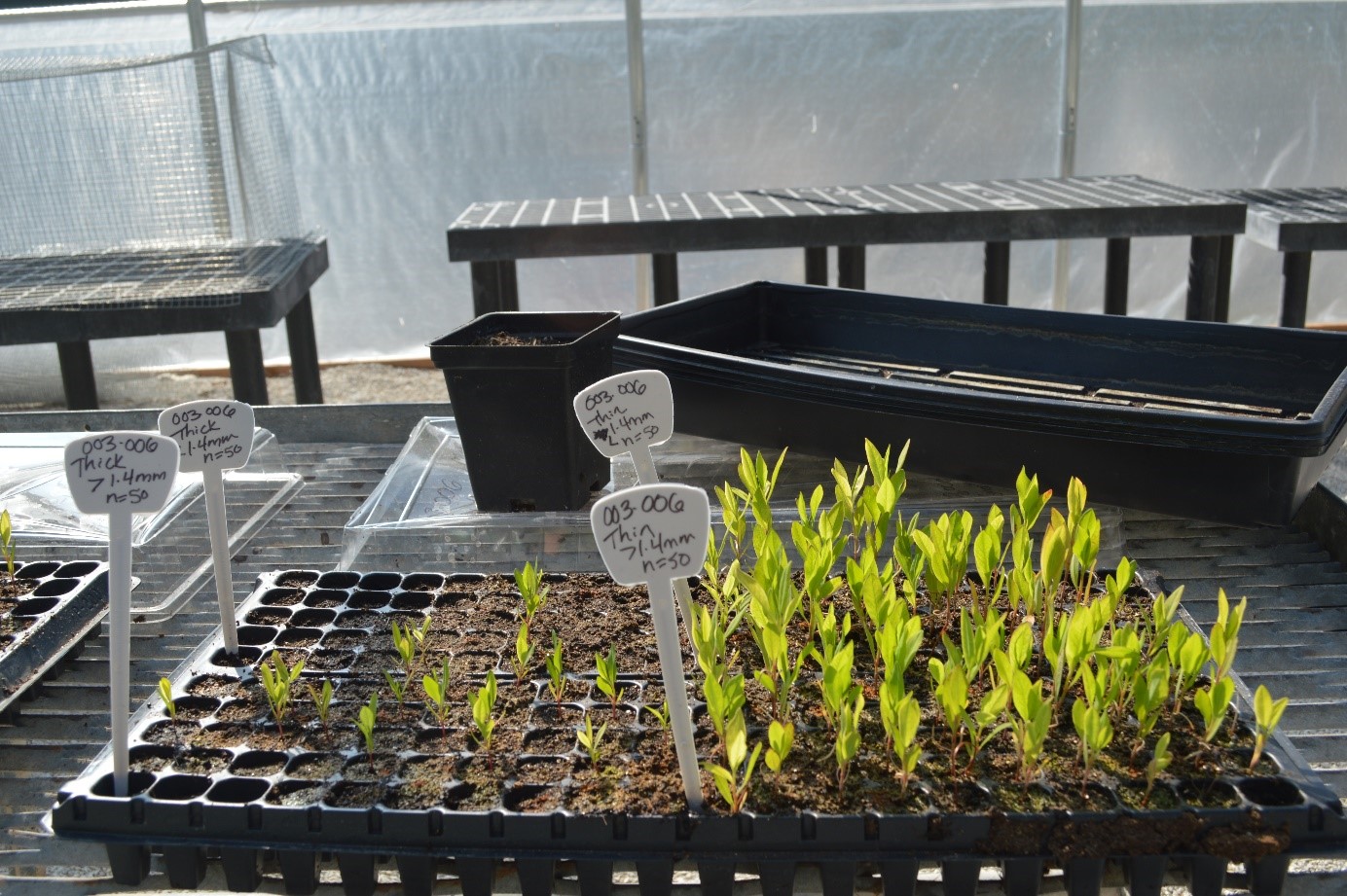

Seedlings germinating from bison dung in late spring 2019. Photo by Natalie G. Mueller

Part I: Plants hitch a ride

During the Ice Age, glacial advances and retreats created big problems for plant populations: they had to find ways to rapidly move across the landscape or go extinct, particularly in the vast mid-latitude grasslands of North America and Eurasia. Many plant species survived by hitching a ride in the gut of an animal. An animal would be attracted by the tasty and nutritious fruit of the plant, but the seeds inside the fruit would pass through their digestive tract and be deposited in a new area in a package of nitrogen rich poop—win, win! Plants that formed this kind of relationship with grazing animals in particular had a unique scheme: since these animals prefer to eat leaves over fruits, these plants have evolved to present their seeds as the centerpiece of a bouquet of tasty leaves. But since many leaf-eating grazers have particularly gnarly digestive systems that have evolved to break down tough, fibrous foods, these plants also have evolved particularly small and hard seeds, which can pass through this digestive gauntlet in good enough shape to germinate on the other side. Another unusual characteristic of such plants is that their seeds will not immediately fall off when they are ripe, as do seeds that are dispersed by wind or water. These seeds have instead evolved to hitch a ride: they are waiting among the leaves to be eaten.

Seed bouquets of sumpweed (left) and goosefoot (right), two plants that were domesticated by ancient Indigenous communities in eastern North America, fall 2018. Photo by Natalie G. Mueller

Part II: Humans arrive on the scene

Imagine you find yourself in the midst of vast grassland on foot and hungry. While this landscape may seem less threatening than, say, a dark forest, it is just as disorienting and difficult to move through. How will you walk through the tall grass without being bitten by snakes, falling into burrows, or becoming hopelessly lost? How will you find water? These problems can be solved if you manage to pick up another animal’s trail.

Tallgrass prairie in late spring with no bison trail to follow (left), versus following a bison trail from stream to stream (right). Photo by Natalie G. Mueller

Now you can walk quickly and with a reduced sense of fear. You are sure to come to a source of water before too long, because other animals need to drink, too. Maybe you’ll even have an opportunity to hunt the very animals you are following. As you follow the trail, you come to a place where the animals have recently been. Their trampling, wallowing, and grazing has created a large opening in the grassland on the banks of a river where they stopped to drink and sleep. Within this clearing, instead of tough perennial grasses, you find dense stands of lush annual plants. These stands have the appearance of a garden, because they are growing in enriched soil with relatively little competition. They are covered in edible seeds just waiting to be harvested. You know you’ll have to do some work to make these little seeds palatable and nutritious, but such a dense concentration of easily harvested food is irresistible.

My colleague, Ashley Glenn, harvesting dense stands of crop wild ancestors growing in a wallow on the tallgrass prairie, late spring 2019. Photo by Natalie G. Mueller

Part III: Plants find new partners

If we fast forward 1,000 years from this hypothetical first encounter, we might find a community of people that has made this patch of grassland their home. In some places, such as Eurasia, North Africa, and highland South America, they have formed such a tight connection with grazing animals that they no longer stalk them as game. The animals have become domesticated cows, goats, sheep, llamas, and alpacas. They are allowed to graze freely, but are penned at night or during certain times of year. The plants they disperse grow around people’s houses and in their corrals, and are also eaten by people. In other places, like eastern North America, the bison herds are still wild, but the plants whose seeds they disperse have become familiar during years of following game trails and building camps and villages in the clearings they create.

In either case, people collect the edible seeds of these plants for food rather than letting the animals eat them all. They save some of the seed and plant new fields, which they thin and weed to give each plant more nutrients and sun to produce seeds for them. Over many generations (which for these plants equate to just a single year), the plants respond to new selective pressures created by humans. Freed from the need to survive an arduous passage through the gut of a ruminant, their seeds can be larger and have less hard coats yet still survive—actually, these attributes are advantageous in their new environment, because people favor seedlings that emerge and grow rapidly by thinning out smaller seedlings from their fields and gardens. This process leads to the evolution of many domesticated crops like quinoa, amaranth, millet, sorghum, buckwheat, and the lost crops that I study.

There is quite a bit of circumstantial evidence that this really is what happened in many different times and places, but the various hypotheses embedded in the story need to be tested. Taking just the North American case as an example, some of the questions I’ve been trying to answer in my field work this year include:

Is it really easier to move through a grassland on bison trails? If you follow these trails, do you find populations of wild crop relatives? Do they form dense stands that are easy to harvest? Are the bison dispersing the seeds of these plants?

Before I started this project, I already knew the answer to this last question was “yes,” from a previous study conducted on the Joseph H. Williams Tallgrass Prairie Preserve, a Nature Conservancy project near Pawhuska, Oklahoma. Claudia Rosas and her colleagues collected 144 dung samples over the course of an entire year on the prairie, and documented two of the lost crops (little barley and sumpweed) in dung. They also collected fur from bison during the annual fall roundup, and documented the same two species (along with many others) in these samples. This is remarkable, since little barley sets seed in May and June; these plants were hitching a ride on a bison’s back all summer! Wallows are formed partly by bison rolling around on the ground, so there is a high potential for these furry animals to both pick up and drop off seeds in these prime locations. Lucky seeds who wallow-hop with bison will find themselves germinating in nitrogen-enriched, well-watered clearings, and ideal place to be a baby plant.

Bison fur in a wallow full of little barley. Photo by Natalie G. Mueller

In our study, we want to see not only if these plants are consumed by bison, but also if their seeds can germinate after the long and treacherous journey through a bison’s gut. We duplicated Rosas’ methods, but instead of collecting all year we are just focusing on the times when we know the lost crops are setting seed: late May-early June and October. We collect fresh dung then wash it and dry it (yes, you can wash dung). In the lab, we sub-sample the dung, taking half of it to the greenhouse to see what emerges from it and the other half to the microscope for seed identification. We are also experimenting with other seed treatments. Some seeds need a long period of ripening in hot weather before they will germinate, and others need to experience cold, wet conditions as a trigger. There are a lot of variables to explore, but luckily there is no shortage of bison dung.

Plants that have germinated from our spring dung collections so far. Natalie G. Mueller

In our study, we are also taking a more controlled, experimental approach. In collaboration with Cliff Montgomery, a Missouri bison rancher, we will be feeding batches of crop progenitor seeds to a bison, then collecting all of his dung systematically. This will allow us to see what percentage of seeds make it through, and what effect this has on germination rates.

Bison romping at Cliff Montgomery’s ranch. We fed crop wild ancestor seeds to one of these fellows in early December 2019 during the final part of our project. Photo by Natalie G. Mueller

This has been very exciting research that has added an important new angle to my understanding of the plants I study. I’ve been cultivating them for years, but before this year I never had a clear idea of how they were first encountered by foragers and why they looked attractive to these highly knowledgeable ancient people. Now that I’ve seen them growing along bison trails and in wallows, I think I understand why people were so inspired to start such a momentous relationship.