Pictured Journeys, Experiences of Descriptions: Tracing ways down the Mississippi

While the Anthropocene River Journey is being experienced in all its visceral reality by the participants paddling down the Mississippi, much of the knowledge generated and exchanged during its journey will be assimilated by an audience situated at a remove. In this post for Temporary continent., Jamie Allen muses upon this distance, making visible the various contradictions inherent within efforts to bridge the gap and communicate “what happened.” Also addressed is the role environmentalist storytelling has played in conveying impacts upon landscapes, the privilege of the storyteller, and anthropocenic spectatorship both on and beyond the river.

The “River Semester” is a “fully-immersive educational experience and opportunity” that sees students—the majority from Augsburg University—undertake a 100-day canoe expedition down the Mississippi River. Considered in all manner of its complex fidelity, it is so very much more than a simple “fieldtrip.” The River Semester involves a group of people—who have not previously met—cozily sardined together in boats, vans, tents and campground shower facilities, as they spend three months travelling down the river, with intermittent access to the media intake diet North Americans have become used to, to creature comforts in general, and with limited contact to friends, family, and wherever they call “home.” The spotty mobile data service that exists in parts of technologized America, in the Mississippi basin, recurrently surprises everyone, and provides a cartography of historical, exclusionary impoverishment; of resource access divides and unbalanced infrastructural investment. The river seems, in this way, to flow both southward and into a past that may never have existed, but nevertheless much has been written about by some very talented white men: Whitman, Twain, Faulkner, among many, many others (also many of whom are not white and not men).

Eroded asphalt seen along the Mississippi riverbank at Prairie du Sac, Wisconsin Veteran’s Park. Photograph by Jamie Allen

This River Semester is unequal parts transformative, educational, trying, frustrating, inspiring, and transcendent, depending on the day, the hour, the moment. It also plays a large and impactful role framing the orientation and impelling the movements of the entire Anthropocene River project, Haus der Kulturen der Welt’s own river-as-framing device and fieldwork excursion, currently underway. Now a multi-year project initiated and led by Joe Underhill, the River Semester is held in collaboration with numerous partners, including an enabling, multiyear, river-long partnership with guides from the non-profit Wilderness Inquiry, and people like Big Muddy Mike from Big Muddy Adventures in St. Louis.

Nicole and Andrew are two people who work for Wilderness Inquiry, as leaders and guides of this years’ trip. They are responsible for logistics, planning, meals, cohering the River Semester group, ensuring its geographic progress, safeguarding the physical and mental health of participants, preventing harm and minimizing impacts. Their multiplicity abounds—Nicole is an architect and illustrator; Andrew a geologist, cartographer, and tech developer (geopoi.us)—and they are both very special human beings. Much more than guides, Nicole and Andrew, individually and as a team, take up roles as chefs, chaperones, teachers, and confidants. In leading a group of mostly non-campers, students, researchers, and others on a trip that oscillates between tests of patience and safety, Nicole and Andrew continuously explore levels of kindness, generosity, patience, and care that one would hope the rest of us aspire to. They both have sage and uncommonly reflective senses of what it is to travel in this way, and why it might be important to experience “nature” (whatever that might mean). How and why people bring things “home” from these experiences of journeys, natures, relations, terrains, and landscapes, and the communities and families that these form, concerns us all.

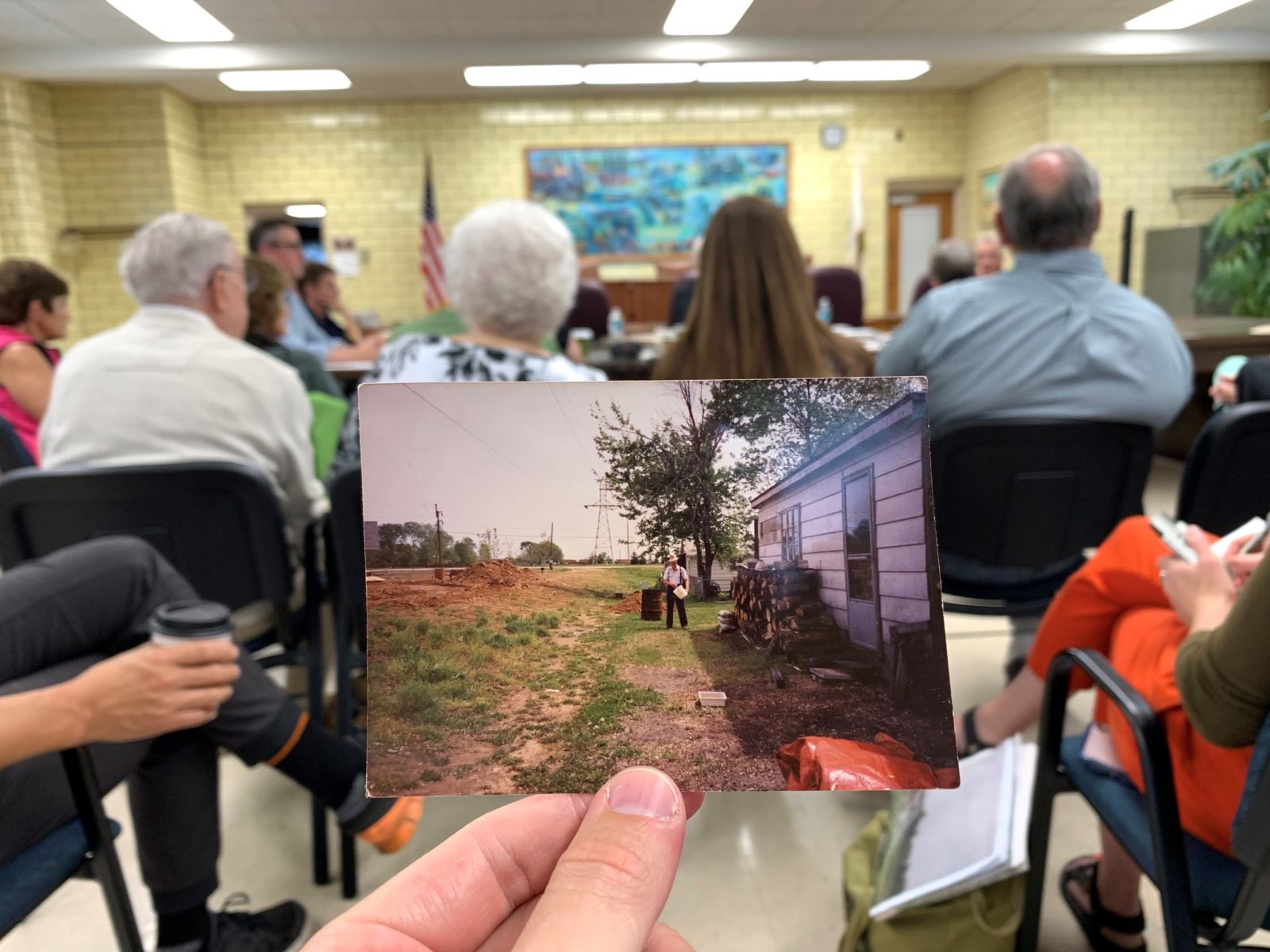

What is not lost on anyone on these journeys are the issues and aspects of anthropocenic spectatorship, disaster tourism, anthropocentric arrogance and extractive epistemologies that trouble the nested programs of the Anthropocene Project, the River Semester, and Mississippi, an Anthropocene River. This last framing makes these troubles particularly acute, perhaps, as it is in part the result of celestial national and institutional agendas aligning to provide resources, bridging cross-Atlantic histories in non-apparent but important ways. In ways that leave a lot of local folks asking “why are they here?”, “what do they want?”, or “what are all these Europeans doing in a town hall in Monsanto Town, Illinois, or in discussion atop the ‘500-year’ levee across from St. Louis?”

The Anthropocene River procession group atop the “500 year levee” along the Mississippi River, just off Monsanto Avenue. Photograph by Jamie Allen

During a portion of the bus tour through Cahokia Mounds, Weldon Spring, and Monsanto Town for Field Station 3, I sat with Nicole and Andrew to talk about if, how, and why they re-represent these journeys to themselves, or to others. The conversation picked up on the impactful and important traditions of American nature and journey literature, spanning generations, intents, and purposefulness. There are, of course, traditions of nature writing and literatures of the journey in all parts of the world. In the United States of America, one could be forgiven for thinking that this sort of authorship became a first art form of this settler-colonial nation, as European literary arts and letters crashed into the Atlantic coast, producing new national imaginaries.

Travel books, blogs, and nature writings are all openings into a literacy that is highly impacting, effectual and even generative of movement, policy, and practice in the United States. Aldo Leopold, whose home was visited by the River Semester crew, situates for this group the importance of simple, direct, and intimate written portrayals of natural environments. The nature writings of Henry David Thoreau helped spur and revive American national, natural narratives; those of Rachel Carlson also induced and inspired a generation on U.S. ecological policy. (Not-so coincidentally, Field Station 2 organizer Sara Kanouse has just embarked on a fellowship at the Rachel Carlson center in Germany, a non-profit devoted to research and education in the environmental humanities and social sciences.) “Does the tradition of environmentalism to which [John] Muir belonged, along with so many other nature writers and ecologists of the past—people like Paul Sears, Eugene Odum, Aldo Leopold, and Rachel Carson—make sense any longer?”, asked environmental historian Donald Worster in his important essay “The Ecology of Order and Chaos”, written almost thirty years ago.

As I write these words, my own attempts at making these Mississippi river encounters and terrains legible, I am transforming value and experience in ways that benefit some, and not others. The story is always the privilege of the storyteller. It is activity that allows for my own mobility, but leaves and fixes many other things, people, and images, in place. Posts to this digital publishing platform and related things like the Fieldnotes ‘app’—supported by offsite development and communications teams in Berlin, and data and media servers in god-knows-where—are “mere” surface-samplings of complex, indescribable relations, and events. Why do I do it? Why were we there? What becomes of all these effort to produce accounts of experience and transformation, these cumbersome and awkward attempts at communicating what happened? Words, video, pictures, sensor data, audio recordings, Instagram posts, tweets, pen-and-paper notebooks, Notepad.app entries, “voice memos”—a proliferative, at times profligate mediality. My hope, if I can offer a little, is that these write-ups and media continue to motivate understandings, and can help make connections to other forms and continuations of relations and events—here, now, or later, and elsewhere, with different kinds of depth, temporality, engagement, and commitment. But also, it would seem that we continuously write, record, and trace because we love it—as ever and sometimes forgivably, perhaps, all-too human.

Picturing one another at the Weldon Springs Army Reserve, while standing on a containment cell of the former U.S. Atomic Energy Commission Uranium Feed Materials Plant. Photograph by Jamie Allen

Sometime after the start of the River Semester, Andrew from Wilderness Inquiry found himself newly busied with taking care of equipment, bodies, and psyches for a fresh and anxious crew of mostly first-time Mississippi river journeyers. Yet he was still compelled, and somehow found the time, to write, composing texts that are truly beautiful contributions to distinguished traditions of American literature, of travelogues as personal, natural histories. Originally published to the blockchain platform Steemit, Andrew’s words as user “gcatalyst (@gra)” are briefly excerpted and linked to below. They employ a mode of experiential description, wrought from experience of the group’s departure from the Mississippi headwaters, tracing and expressing in ways that provoke responses of care and inspire custodianship; leaving no trace but the words of a sensitive and thoughtful human, being in the world. I am grateful to Andrew for his writings, and thankful to you for taking the time to read both his, and my own.

Anthropocene River Journey: The Source

Excerpt by gra (62) on steemit.com

This journey starts at a pristine lake. The lake may seem somewhat arbitrary; a random expanse in the upper reaches of a vast watershed that goes in many directions and bisects the land. There are other tributaries and drainages that extend much further when followed to their source, but they do not bear the same coveted “headwater” title.

Lake Itasca. Photograph by catalyst (@gra), steemit.com

Here we are at Lake Itasca, where the rice grows wild and rains and springs accumulate to form the beginning of a great river. The river here is more like a creek in that it can be crossed by hopping on stones rather than swimming or wading, but unlike the many streams that feed the lake, the outlet at the northern end flows all year round. Itasca also has the distinction of being the highest elevation lake feeding a non-ephemeral stream that flows into the Mississippi. It seems the headwater designation is not entirely arbitrary. Perhaps Itasca is a unique place after all…