The Mississippi Basin: An Operational Landscape

Drawing upon the methods employed by the Commodity Flows seminar of the Anthropocene River Campus in New Orleans, architect and urbanist Nikos Katsikis describes the assemblage of “operational landscapes” that are tied to the Mississippi basin. As Katsikis’ mappings of different flows demonstrate, over the course of several centuries, this—inherently flawed—logic of operationalization has seen the Mississippi transformed into one of the many dynamic “hinterlands” of the Anthropocene.

The meta-geography of the conterminous United States is often dominated by an image of densely inhabited, intensively productive coastlines (those abutting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, but also those along the Great Lakes and the Gulf of Mexico); and a sparsely inhabited, largely agricultural interior of lower economic intensity. To a large extent, this “great interior” corresponds to the drainage basin of the Mississippi River: a riverine system of more than 250 rivers that flow into the Mississippi, across parts or all of thirty-one US states, plus two Canadian provinces. Indeed, while the Mississippi Basin drains more than 40% of the contiguous US, it hosts less than 25% of its population. The map in figure 1 highlights the boundaries of the basin’s dominance over North America, relating it to the distribution of population densities. However, what defines this extended system is not so much the cities and metropolitan regions—the agglomeration zones of “concentrated urbanization”—but rather the broader and historically pervasive operationalization of natural systems: an assemblage of “operational landscapes,” where nature is put to work. Landscapes of primary agricultural production, (largely waterborne) circulation, and waste disposal. It is through the various assemblies of these operational landscapes that the Mississippi Basin constitutes the basis for the material economy of the US, and, to a certain extent for commodity flows of the world.

Through the map of “cropscapes” (figure 2), the dimensions of Anthropogenic operationalization across the basin are revealed. The Mississippi Basin hosts more than half of all agricultural land within the US and, at the same time, almost 30% of its land area is dedicated to industrial farming, in particular to monocultures of corn and soybeans. Out of the almost 1 million km2 of farmland covering the basin, more than 60% is dedicated to a rotation between corn and soybeans, mostly concentrated along the upper Mississippi Basin, with around 100 million tons of the resultant crops exported. If the agricultural productivity of the landscape is the foremost process of operationalization across the basin, the second is the circulation of mostly dry-bulk, primary commodities, including, but not limited to, agricultural products. The map in figure 3 reflects the general distribution of flows of freight traffic across the US, both road traffic (trucks) and waterborne traffic. The historical importance of the Mississippi network of waterways is still prevalent as waterborne freight transport remains by far the most cost-effective option, especially when transporting bulky commodities (with low value to weight ratios), which characterize the productive output of the region (agricultural products, chemicals, fuels, minerals). Almost 4% of all annual US freight volume is transported through the upper and lower Mississippi River waterways, a system that also has stitched along it a series of intermodal ports bringing together barge, truck, and rail traffic.

These geospatial layers start revealing the basic dimensions of operationalization through which the Mississippi Basin is assembling a multitude of operational landscapes of production and circulation of primary commodities into a “horizontal factory”. But as processes of operationalization intensify in the constant search of profit, the capacities of natural systems to support them are gradually exhausted and need to be compensated through recurring investment and eventual capital intensification: fertilizer inputs substitute the lost fertility of the soil, while constant drainage is required to sustain navigational depth across the waterways. At the same time, efforts to expand this capacity often lead to further degradation. The increased used of herbicides and genetically modified crops leads to the evolution of more resistant “superweeds” and “superbugs,” while drainage efforts through tilling lead to increased water pollution, erosion, and sedimentation—all of which require further investment in infrastructure and inputs, in a constant struggle to maintain the operationality of the landscape. A vicious cycle of increasing investment, commodification, and intensification, only to sustain thinning profit margins, lays bare the limits of operationalization, as its consecutive waves exhaust the “ecological surplus” of the Mississippi Basin.

As the underlying logic of operationalization is driven by the search for profit, the hyper-productivity of the region yields questionable results. The metabolism of the agroindustrial system offers a lucid example: While agricultural yields continue to rise, the region is barely producing any food. More than 50% of the corn and soy production ends up as animal feed, with its nutritional contribution deteriorating as it flows through the meat processing industry. What is even more striking is that a growing amount of crops is not even part of the food/feed nexus, but are rather inputs for the biofuel industry. In fact, to a large extent, the Mississippi Basin is turning into an energy landscape, characterized by a quite paradoxical metabolism: as large quantities of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers need to be diffused over the Cornbelt to compensate for the exhausted fertility of the soil, tons of fertilizers are shipped through the Mississippi transport network, from the fertilizer processing and mixing plants that are stitched along it, and which are interwoven with the pipelines providing their main input: natural gas. In this rather absurd cycle, one form of energy (natural gas), is eventually turned into another (biofuel), having been transmitted through nitrogen fertilizers and plants. Moreover, excess nitrogen is “returned” to the riverine system in the form of water pollution, reflected in figure 4. This map overlays nitrogen deposition along the watersheds with the location of natural gas pipelines and fertilizer plants, disclosing this irrational interplay that is facilitated through subsides and regulatory frameworks aiming to address agricultural surpluses and trade crises.

Operational landscapes, such as those composing the Mississippi Basin, largely constitute the dynamic “hinterlands” of the Anthropocene, the basis of the material economy of the planet. Grasping the structure and dimensions of the material economy requires a critical interrogation of the main devices through which trade and production are monitored—frameworks that are often geared towards the measurement of only economic value, obscuring the associated negative externalities, both social and ecological, and thus accommodating their spatial and temporal displacement in the search for profit. Operational landscapes are thus revealed as profit landscapes, based on the appropriation, not so much of human, but of extra-human work. As the capacity of nature to contribute free work is gradually exhausted, operational landscapes reveal the limits of dominant modes of development and pose questions to the limits of capitalism as a whole.

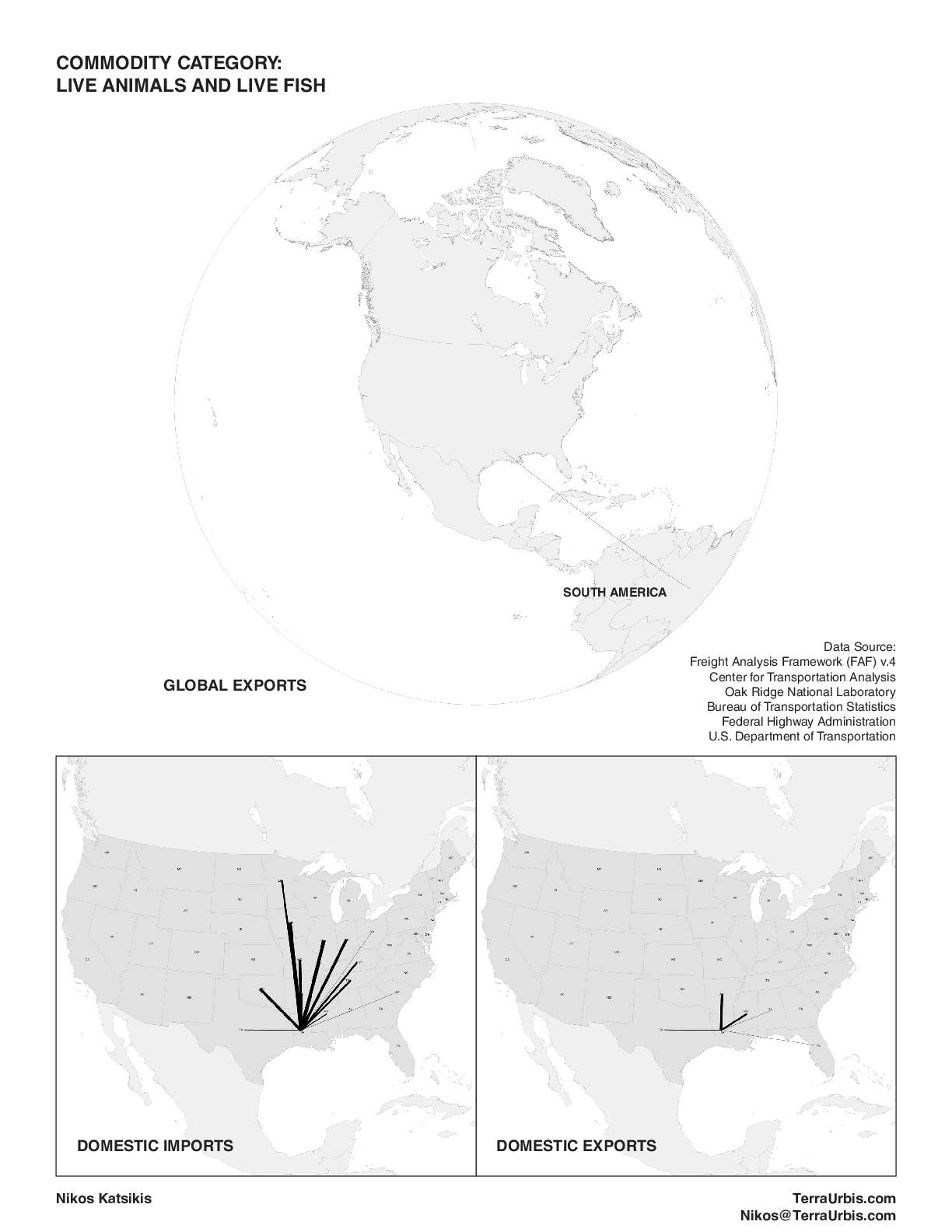

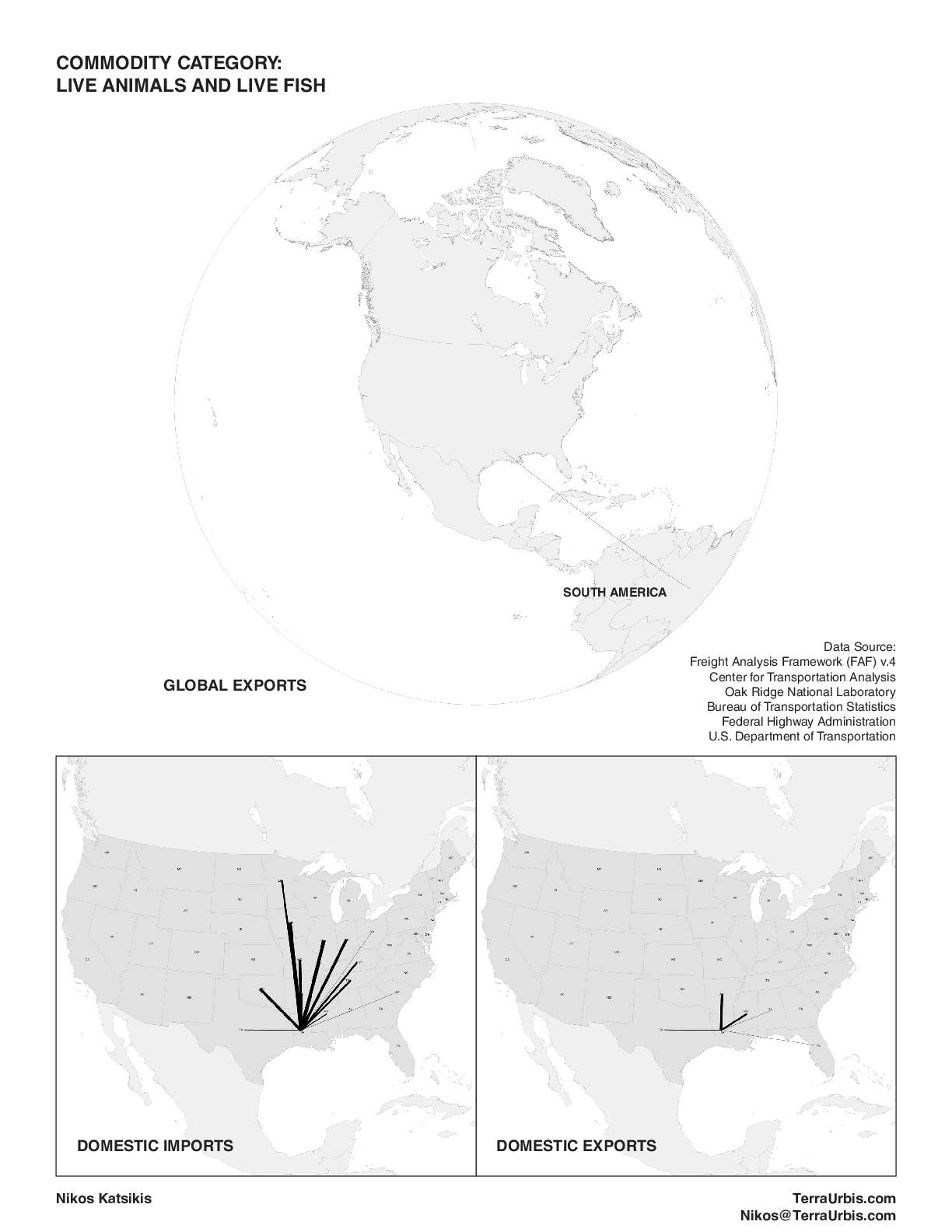

This atlas reflects the work of the mapping workshop organized during the Anthropocene River Campus that took place in New Orleans in November 2019, which aimed to reveal the structure of the material economy across parts of Mississippi by mapping the flows of commodities in and out of the state of Louisiana. Workshop participants introduced a series of items, which had to be classified according to the standard commodity classification systems, the 5-digit Standard Classification of Transported Goods (SCTG). Using as a background the general description of the operational properties of the basin provided by the maps in figures 1-4, and the latest version of the US Commodity Flow Survey and the Freight Analysis Framework (US Census and Bureau of Transportation Statistics, 2012), the workshop mapped the weight and volume of domestic and international imports and exports from and to the state of Louisiana for 15 different categories of commodities, shown in the form of an Atlas. While by no means complete, this exploration offered a glimpse into the structure of trade around Louisiana, but above all interrogated the potentials, limitations, and underlying logics of bureaucratic data surveys and geospatial data, highlighting how operational landscapes are also geospatial data constructs.

Download Full PDF (15 Pages)