The Mississippi River Provides Insights into the World of More than 300 Million Years Ago

The impact of coal and fossil fuel emissions on anthropogenic climate change has been well established. But how did coal form originally? In this excursion into the Carboniferous age, geologist Colin Waters traces back the origins of coal in the region that today forms the Mississippi River system.

During the geological time period known as the Carboniferous—which spanned from around 299 to 359 million years ago—in many respects the Earth would have appeared an alien world. The name Carboniferous comes from the vast accumulations of coal that developed across Midwestern and Eastern North America, Northern Europe, and Asia at this time; this was the first development of coal on such a large-scale in the Earth’s 4.6 billion-year history. The Carboniferous age is separated into the Mississippian (early Carboniferous) and the Pennsylvanian (late Carboniferous), a division that broadly distinguishes between the mainly limestone successions of the Mississippian (of the type found around the upper Mississippi Valley) and the coal-bearing strata of the Pennsylvanian (named after the North American state in which coal deposits are extensive).

The arrangement of the continents was markedly different to today’s configuration: the late Carboniferous collision of Laurentia (present-day North America, Northern Europe, and Northern Asia) and Gondwana (present-day Africa, South America, Antarctica, Australia, and India) resulted in the development of the supercontinent of Pangea. This collision also generated the Appalachian Mountain belt, which was comparable in scale to the modern-day Himalayas and formed part of a mountain chain that extended across Europe (the Atlantic Ocean had not been formed at this point).

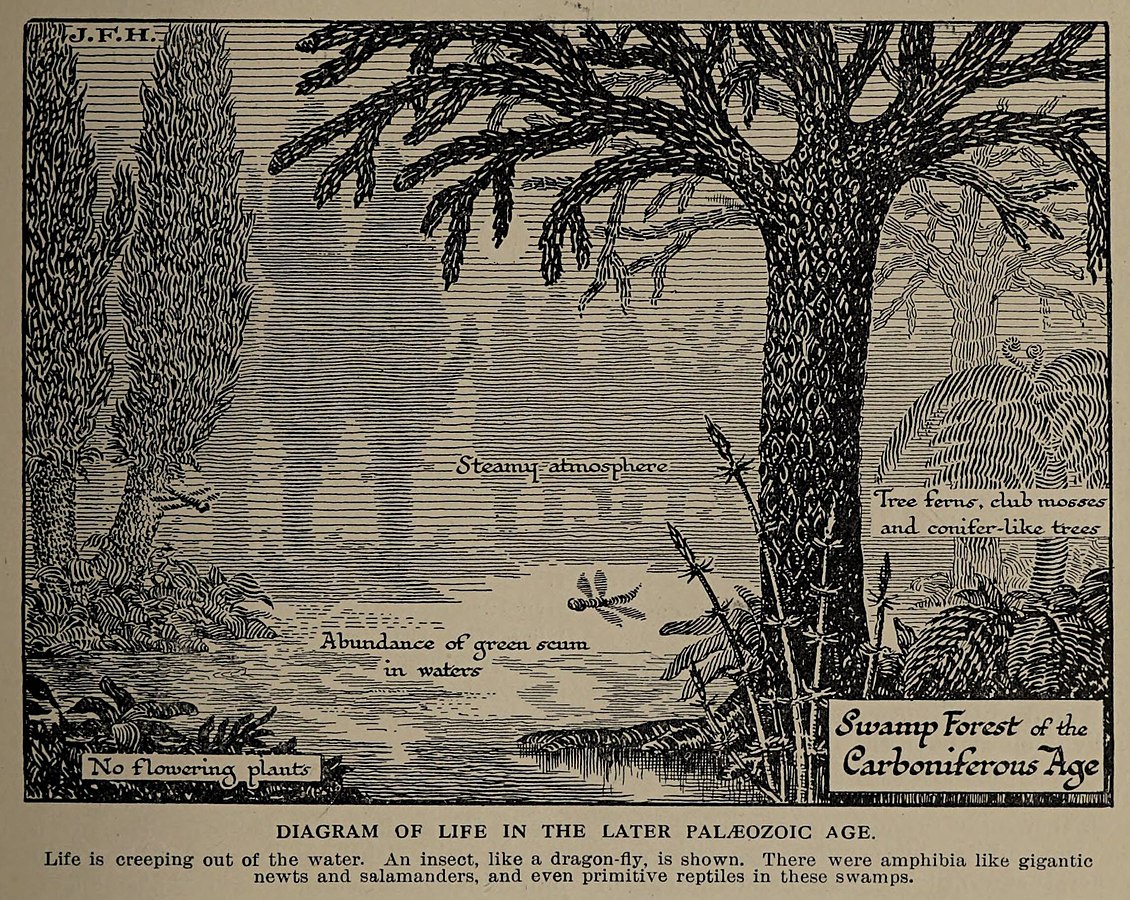

Vast coal deposits, including those of the Illinois Basin located in the Mississippi River Valley, started as extensive swamp forests, growing on lowlands that were located near the Equator at the time. These tropical and monsoonal forests comprised tree-like plants that were very different from the angiosperms that dominate our modern woodlands. Seedless vascular plants such as lycopsids (giant club mosses), sphenopsids (horsetails), and tree ferns flourished to form these forests tens of meters in height; modern relatives of these plants typically grow only tens of centimeters high. Populating these same forests were the first land snails, dragonflies, millipedes, scorpions, and spiders, with land-based reptiles appearing at this time too. The swampy conditions meant that, upon death, the plants did not completely decay, but formed carbon-rich peat deposits, which on subsequent burial, compression, and some degree of heating transformed into coal. Given that it takes about ten meters of peat to produce one meter of coal, and that some of the resultant coal seams are greater than ten meters thick, these Carboniferous coal accumulations represented a colossal sink of carbon, ultimately resulting in reduced atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations. This great expansion of forests during the Pennsylvanian period also, through photosynthesis, produced an atmosphere enriched in oxygen by up to 35 percent, as compared with the 21 percent in the present day. Such a world would be prone to wildfires, but at the same time permitted the evolution of invertebrates that could grow to great sizes.

Swamp Forest of the Carboniferous Age Illustration by J. F. Horrabin

Certainly, this would be a strange world to visit, but one that can be envisaged through comparisons with the modern Mississippi Delta. During his second journey to North America, Sir Charles Lyell—one of the founding fathers of the science of geology—observed that, when visiting the Cypress swamps of the Mississippi, “no sediment mingles with the vegetable matter accumulated there from the decay of trees and semi-aquatic plants,” which explained the absence of sediment in Carboniferous coal.1

Mississippi Cypress Swamp Image by Julie Delio

In addition, it is thought that ancient precursors to the Mississippi River existed in the region during the Carboniferous age. The uplifting of areas due to the continental collision between Laurentia and Gondwana caused increased erosion along the line of the Appalachian Mountains, aided by monsoonal climatic conditions. The vast supplies of sediment that this produced were transported by river systems flowing southwestwards in an area comparable to the modern Mississippi; the Appalachians continue to act as the eastern flank of the modern Mississippi River system to this day. These ancient rivers deposited their sediment loads to form huge areas of lowland river floodplains and deltas during the Pennsylvanian period, the geometries of which can be compared with the modern Mississippi River system. In 1954 Harold N. Fisk and his co-researchers provided some of the first detailed sedimentological analysis of the development of deltas using the Mississippi Delta.2 This has become widely used as an analogy for ancient delta-formation and notably for Carboniferous coal formation.

Satellite image of the Mississippi Delta Image by NASA

The decreased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere during the Pennsylvanian period is thought to have been a driver in the development of large ice sheets at the South Pole over Gondwana, with multiple phases of glaciation and deglaciation causing sea levels to fluctuate, perhaps by up to one hundred meters. These fluctuations produced repeated cyclic successions of marine and lake muds, river and delta sands, and peat, ultimately lithifying once buried to form shale, sandstone, and coal. Such variations in sea levels are comparable to, and resulting from, the same processes as those recorded over the last 2.6 million years of Earth history (the Quaternary)—when ice sheets waxed and waned at both poles based on a natural tempo forced by the orbital passage of the Earth around the Sun.

However, there is a difference between modern and ancient icehouse conditions. More than 300 million years ago, the trend was moving toward cooling temperatures and reducing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Some 300 billion metric tons of coal has been mined globally during the Anthropocene. Our burning of this resource has returned vast quantities of carbon back into the atmosphere, in particular as carbon dioxide, with concentrations increasing to levels nearly 150 percent of those at the time of the first combustion of coal for steam at the start of the Industrial Revolution—only two centuries ago. The consequences this has for global warming and sea-level rise through melting ice sheets will significantly impact flooding in the Mississippi River Valley and in coastal regions globally, over future decades and continuing for millennia.