Traces and Symptoms

The semiotics of anthropogenic markers

What kind of sign is a marker? This question is at the heart of the multi-disciplinary discussions that animate the conversations of these dossiers, and is fundamentally a question of semiotics: the study of signs. In this reflection, science historian Jürgen Renn and literary scholar Nathaniel LaCelle-Peterson sketch out how the dual role of markers as traces in the strata and symptoms of the dangerous destabilization of the Earth System turns them into a crucial interface between natural archives and human societies.

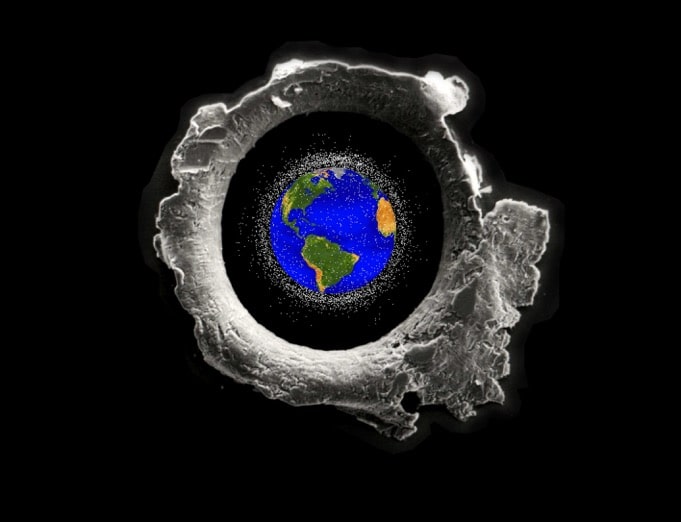

View of Earth with the SYNCOM IV communications satellite, January 10, 1990. Courtesy NASA, Public Domain

How does a marker work? This question might appear to have an obvious answer. At a practical level, a chronostratigraphic marker must provide the globally synchronous “stable and reliable” signal of a Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP).1 The various candidates—novel materials, radioisotope signatures, combustion products, sudden changes in biota—are thus subject to rigorous analysis based on the pragmatic criteria that seek to establish their capacity to enact this technical task. But for geological signals more generally and anthropogenic markers specifically, this is only a partial answer: the material signals of the Anthropocene are not just interesting pieces of trivia that have an uneasy life between a number of scientific and humanistic disciplines; they fairly urgently reveal something about the scale and trajectories of a rapidly changing Earth System, and the unsalutary role of our societies in it.

Throughout these dossiers, markers are described in terms of signals, evidence, traces, unintended consequences, signatures, and symptoms—along with the term “marker” itself, these are all terms for specific kinds of signs. The study of signs and how they work is a field of study in its own right, semiotics, which surprisingly is seldom mentioned in discussions of where and how we can mark the beginning of the Anthropocene. As a discipline, we can see semiotics emerging in the work of the polymath Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914) and the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913). The central problem that semioticians puzzle over is how, exactly, do signs work? Semiotics is an approach familiar to language and media theory—but what insights does it offer in our context, where the function of the Earth System is at stake, and not simply the problem of communicating effectively in a symbolic system? The answer lies precisely in the need to better understand the dual function of markers in their scientific role: the GSSP will distinguish the beginning of the formal geological section of the Anthropocene in strata; at the same time, their societal implications serve as warning signs of an impending catastrophe.

In order to analyze this dual role, it may be useful to take a closer look at Peirce’s approach to semiotics, which takes the track of identifying and classifying different kinds of signs based on how they work. To situate the marker, we can begin with the three principal kinds of signs Peirce proposes: indices, icons, and symbols, each distinguished by a difference in how it relates to the thing it represents.

Indices, or “indications,” are “physically connected to” what they represent: the classic example is a weathervane, which points in the direction of the wind because of the wind—or a sundial, which indicates the time of day.2 As we will see later, this category of “physically connected” indicators is still quite broad, but compared to icons and symbols, what stands out is that the object—the wind’s direction or time of day—directly affects how the index works, aligning the weathervane or casting a shadow.

Symbols, on the other hand, work to communicate something because they are a part of a system that doesn’t have to bear any causal relationship to what is being represented—“horse,” “Pferd,” and “caballo” are all equally valid and arbitrary ways of pointing to a specific kind of mammal, and each depends on the larger systems of their language (English, German, Spanish) and the Latin alphabet to make sense.

And icons, finally, are “likenesses,” which “convey ideas of things they represent simply by imitating them.”3 While icons are supposed to have some physical semblance to what is being represented, as Peirce insists, we are misled if we “surmise that zebras are likely to be obstinate, or otherwise disagreeable animals, because they seem to have a general resemblance to donkeys.”4

In this schema, where should we put markers? As they are related by cause to the changes in Earth System processes characterizing the Anthropocene, markers are first and foremost indices. A specific kind of index is, according to Peirce, the “track”: one example is paw-prints in the snow, which physically register the presence of a fox, say, but with some temporal and spatial delay. This notion clearly fits the task of identifying anthropogenic markers and of assessing what and how these markers will be preserved in the far future—a task that, at the same time, renders the present condition comparable to the rich natural archives of the past.5

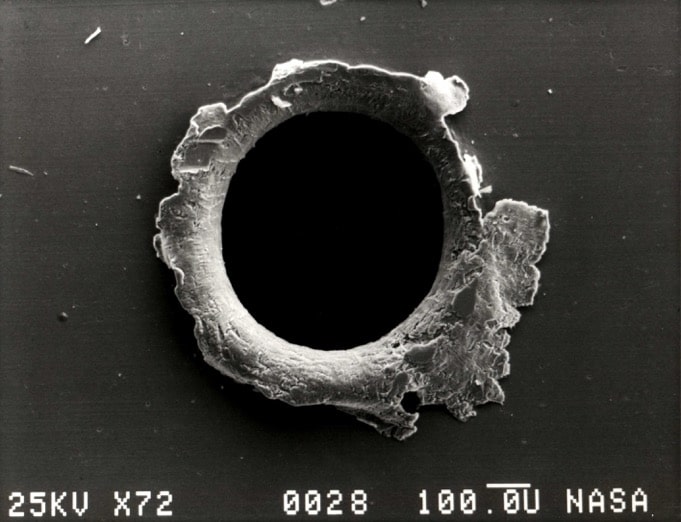

The clearest example of such markers understood as tracks is the technofossil. A technofossil (e.g. a plastic bag) is clearly not an icon as it does not depict a human being or the Earth System. At the same time, it is not just a symbol because it is very much not arbitrary: as a “geological signal” a technofossil stands as part of the drastic changes in the functioning of the Earth System that could likely be preserved in future strata, regardless of the words or meaning we attach to it.6 But we should also remember that there are other trace fossils of our strange moment that will be preserved, not in strata, but elsewhere in the Earth System. One such possible marker is satellite debris. Around Earth lies the so-called “graveyard orbit,” out beyond the operation orbits of still-functioning satellites. In the graveyard orbit, defunct satellites have expected orbital lifetimes on the scale of millions of years.7 The graveyard orbit is global and persistent; it is a collection of technofossils and it is quite accessible, visible with a small telescope on a clear, dark night anywhere in the world.8 As the careful discussions of the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) make clear, for scientific claims to be made and evaluated about stratigraphic makers, their indexical link is crucial.

But markers are never just indices either, since they typically also possess a symbolic dimension. To his credit, Peirce was always ready to consider examples that do not neatly fall into one category or another. Maps, for example, were for Pierce “likenesses” and also indices, because they include information that scales or “points” their image back to the territory. Unlike a weathervane or a sundial, markers are never such perfect signals. While the choice of an anthropogenic signal as a marker is made largely on technical grounds, because chronostratigraphy is about the practical problem of organizing the material that makes up Earth history, such a choice also involves an interpretative, symbolic dimension related to the theoretical construct to be supported by the marker, in this case the Anthropocene concept. If we are just looking for a good abstract symbol of the Anthropocene, we could reach for the famous hockey stick graphs of the “Great Acceleration” that repeat throughout Anthropocene discourse; but, of course, these are not markers.

The intimate relation between the technical function of a geological marker and a broader causal narrative may be illustrated by the debate over the choice of iridium as a marker of the Cretaceous-Palaeogene boundary.9 Its acceptance as a marker crucially depended on the acceptance of the bold hypothesis that the mass-extinction of the dinosaurs was caused by the impact of a massive meteorite and the resulting end of the Cretaceous. The impact hypothesis explains the anomalous amounts of iridium discovered in a very thin clay layer separating the geological strata.10 But since, at first, an “impact-driven” mass extinction was not universally accepted, also the choice of a marker remained controversial. It took over thirty years for evidence and consensus to accumulate in support of the meteorite hypothesis. Since “many researchers now regard the impact as coincident with, and the primary cause of, the mass extinction event (or at least as a powerful and geologically instantaneous coup de grâce for a global ecosystem perhaps weakened by climate change and enhanced volcanic activity)”, there is finally “a rationale for using the impact event and its debris layer as a means to define the Mesozoic-Cenozoic boundary.”11

The example shows, for the case of geological markers, that an index cannot be separated from the process of its interpretation and hence from its role as a symbol within a larger theoretical framework. But the reverse is also true: what might stand as a plausible symbolic marker must still first prove adequate as an indexical marker. This may be illustrated by the discussions surrounding the Orbis Spike hypothesis, which proposes to mark the onset of the Anthropocene by an alleged 1610 spike in atmospheric CO2—supposedly the result of rapid land use changes in the Americas, following the population collapse after colonial incursion and genocide of the so-called “Columbian Exchange.” The proponents of the hypothesis, Simon Lewis and Mark Maslin, are surely right when they write that “the event or date chosen as the inception of the Anthropocene will affect the stories people construct about the ongoing development of human societies.”12 In this sense, the Orbis Spike would serve as a perfect symbol, pointing to important processes driving the Anthropocene.13 But while the symbolic importance of the date is clear and relies on incontrovertible facts of colonial history, from a paleoclimatic perspective, it remains controversial because the spike itself does not pass the threshold of reliable measurement.14

Markers as symptoms and warning signals

For geological markers, their indexical function for stratigraphy and their symbolic role in theoretical accounts of geological change is, as we have seen, inseparable. But for anthropogenic markers yet another important semiotic dimension is added: their symptomatic meaning. In the introduction to The Anthropocene as a Geological Time Unit, the authors describe the process of designating the geological Anthropocene as a reading of symptoms:

One might use a medical metaphor, in that the characterization and definition of a geological Anthropocene may be said to be diagnosing the condition of a planet through a particular set of symptoms, against the background of a very long family history. Such analysis of the geological Anthropocene does not, though, investigate the causes of the condition too deeply, nor does it offer any treatment plan or much in the way of a prognosis.15

Markers, however, understood as symptoms, point in fact beyond the geological Anthropocene. The concept of symptom has a long tradition in the history of medicine and is also mentioned by Peirce as a possible kind of index. Symptoms relate seemingly isolated signals to a systemic problem. Dealing with symptoms one by one will typically not solve a problem, and may even serve to make it worse. In a psychoanalytical tradition, symptoms may even be interpreted as distorted attempts at communication. A proper cure requires holistic interventions, based on a systemic understanding of the underlying problem.

Understood as symptoms, anthropogenic markers remind us of the malaise that characterizes the systemic condition of the entire Earth System, and of the crisis this condition means for us humans. In the sense explained above, they may even be read as warning signals of the altered Earth System that we may use to reorient our actions in a holistic way toward a resolution of the crisis. Not all markers are equally suitable as such warning signals of course, but many of them may be interpreted in this way. Even the much-discussed plutonium signal can be read as more than just a convenient stratigraphic trace of our entry point into the Anthropocene, or as a symbol of the Great Acceleration. Read as a symptom, we are persistently reminded of the dangerous path we have chosen in exploiting the powerful forces of science and technology for self-destruction rather than for finding a path into a “Good Anthropocene,” to use a phrase by Paul Crutzen.

Reading anthropogenic markers as symptoms is not just a multidisciplinary effort, involving the geosciences, the social sciences, as well as the humanities, with each contributing their separate expertise like so many specialists crowding around the patient Earth. It represents the far greater challenge of developing a holistic, systemic understanding of its state, overcoming traditional conceptual and methodological boundaries, and not shying away from moving beyond diagnosis to the urgently needed therapy.

Stratagrids (Max Stocklosa and Daniel Wolter) 2016 Courtesy Stratagrids

Making markers

We hope that our excursion into the world of semiotics has helped to clarify why markers are so challenging. Markers are caught between their status as “tracks”—something left behind which will be preserved upwards of millennia in strata—and symptoms, which show us here and now the patient’s malaise, possibly pointing to therapeutic interventions that do more than just cure the symptoms. In both cases, markers work as an index, inseparable from the object they represent. To be effective signs in either case, they must be effective indices; they must be physically related to the material of Earth history, and symbolically to the malaise of the Earth System that we see in the trends of the Great Acceleration, exceeding the stability of the Holocene planet.

The discussion of anthropogenic markers orbits two hard questions: How can we use stratigraphic markers as symptoms of the Anthropocene state of the Earth System? And, at the same time, are the symptoms that we can identify perhaps suitable as markers in the stratigraphic sense? Throughout these dossiers, a dialogue forms between those who are compelled to read the symptoms and those who are compelled to follow the “tracks.” The challenge for us is to keep translating markers into symptoms, and closely examining symptoms, to see if they are markers. Ultimately, markers work to stand as the interface between the breathtaking vastness of natural archives and the complex, vertiginously symbolic world of human societies. A good marker is inseparable from both.

Jürgen Renn is Director at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin and honorary professor for History of Science at both the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and the Freie Universität Berlin. His most recent publication is The Evolution of Knowledge: Rethinking Science for the Anthropocene (2020, Princeton University Press).

Nathaniel LaCelle-Peterson is the managing editor of Anthropogenic Markers: Stratigraphy and Context. In the fall of 2022 he will begin doctoral study in media studies and comparative literature at Yale University.

This work is licensed under CC-BY-4.0

Please cite as: Renn, J, N LaCelle-Peterson (2022) Traces and Symptoms. The Semiotics of Anthropogenic Markers. In: Rosol C and Rispoli G (eds) Anthropogenic Markers: Stratigraphy and Context, Anthropocene Curriculum. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. DOI: 10.58049/FE4B-1X30