Flinders Reef, Australia

Site Introduction

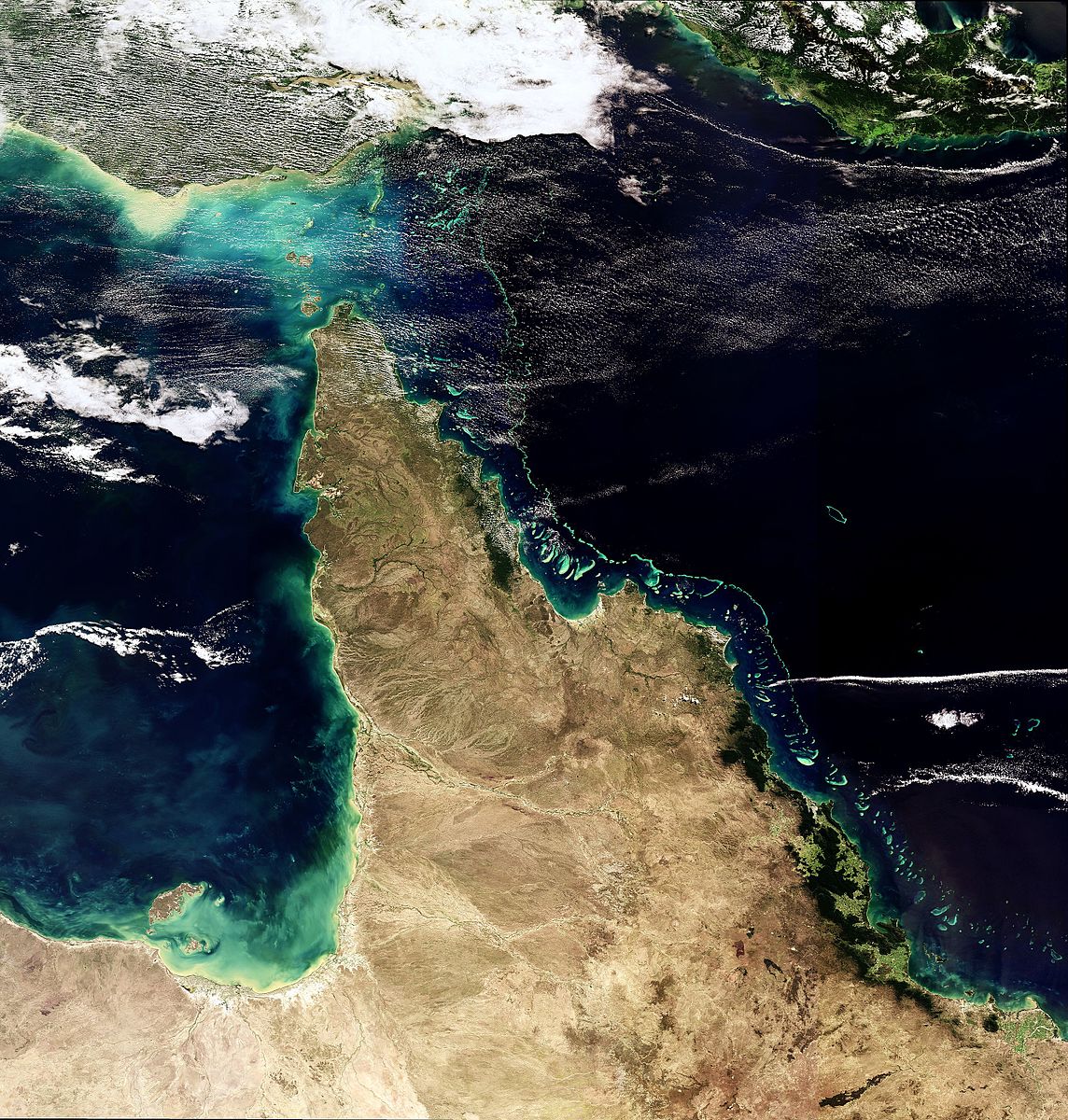

Flinders Reef is an oceanic reef in the Coral Sea off the northeast coast of Australia. Flinders is around 120 kilometers further out than the main band of the Great Barrier Reef, the world’s longest reef system, which stretches for more than 2,000 kilometers along the northeast coast of Australia and makes up 10 percent of the world’s reef ecosystems. Protected since 1975, the Great Barrier Reef encompasses around 3,000 coral reefs that are home to myriad fish, anemones, crustaceans, sponges, jellyfish, turtles, mollusks, worms, sea snakes, sharks, and rays.

Flinders Reef lies around 250 kilometers from Australia’s northeast coast and, at forty kilometers long, is one of the largest separate reef systems in the Coral Sea. Coral reefs are threatened by a variety of local and global anthropogenic pressures. Locally, increased development and agriculture on land has resulted in more polluted water on the reefs, as well as pressures from fishing and tourism. Globally, the carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere by the burning of fossil fuels has caused both rising sea temperature (via global warming) and ocean acidification (the oceans absorb some of the extra carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, which forms carbonic acid and thereby increases the pH of the water), both of which threaten corals. Warmer ocean temperature is one cause of coral bleaching,1 and although corals can recover from bleaching events given enough time, global warming means that the frequency and intensity of bleaching events is increasing, making it harder for corals to recover. Meanwhile, ocean acidification decreases the amount of carbonate ions in seawater, which may cause coral skeletons to grow more slowly and become weak and brittle.

A satellite image of north Queensland, Australia. The Great Barrier Reef is visible off the northeast coast, with Flinders being further out towards the bottom of the image. Photograph by European Space Agency, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO Bleached staghorn coral in the Great Barrier Reef. Photograph by Matt Kieffer, Wikimedia Commons , CC BY-SA 2.0 AT

Location of the Core

The GSSP-candidate core was collected from a Porites sp. coral, a massive stony coral that grows to around four meters in height and six meters across. As corals grow, they preserve a record of the water chemistry in their exoskeletons2 that allows scientists to reconstruct past environmental and climatic conditions. Porites sp. are particularly useful for analysis since they have a long lifespan (they can live for hundreds of years) and grow continuously. The Flinders core has a growth rate of between 0.8 and 1.6 centimeters per year. The varying density of the skeleton during the year produces annual growth bands, which provide a high temporal resolution that can be accurately dated. Stable isotopes (which contain information about past temperature) and trace elements are incorporated into the coral skeletons, allowing scientists to reconstruct past environmental and climatic conditions.

Because Flinders is an offshore oceanic reef, it is less vulnerable to human influences than those closer to the coast, which are subject to more impacts from tourism and receive pollution from the coast and rivers through sedimentation. This means the signals that Flinders records are more indicative of global and regional changes than local ones.

Flinders Reef in the Coral Sea has been monitored and studied for decades, and the Australian Institute of Marine Science holds the world’s largest coral archive, so there is a good foundation of knowledge to back up the Flinders findings. The area is also a marine park, so it is protected and actively managed.

Example of a Porites sp. coral. This specimen is growing off St. Marie Island, Madagascar. Photograph by Jens Zinke © All rights Reserved

The Core and Results

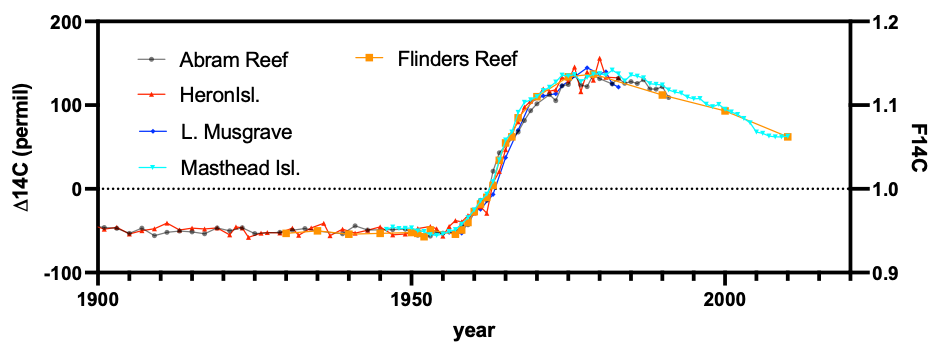

The two Flinders Reef cores preserve archives from 1708 to 1992 (FLI01A) and 1835 to 2017 (FLI05A). There is a clear “bomb pulse”3 recorded in carbon-14 levels that rise dramatically around the 1950s and peak in 1975, before slowly decreasing—a result that is correlated in coral samples from across the Great Barrier Reef. Meanwhile, changes in the abundance of other carbon isotopes (carbon-12 and carbon-13) reflect the addition of anthropogenic carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and oceans from fossil fuel burning. Plutonium concentrations in the Flinders corals were relatively low, yet indicated some typical spikes associated with major nuclear weapons testing periods in the Pacific Ocean in the 1950s and 1960s. Mercury levels as indicators of atmospheric pollution were also low, testifying to the pristine nature of the coral reef location.

The cores also record changes in ocean temperature (likely caused by the climate crisis) through oxygen isotopes and strontium/calcium ratios, with a distinct rise in temperature starting in the 1850s and accelerating in the 1970s. Levels of boron isotopes reflect ocean pH and have a lot of variability over the 300 years the coral records, but show a slight downturn in the second half of the twentieth century. The lowest—and therefore most acidic—pH level recorded in the coral is found around the year 2000. In the 1950s, the nitrogen isotopes show a reverse of the previous long-term decline, most likely related to ocean circulation changes in the South Pacific.

Carbon-14 of Flinders coral core (orange) compared to published records from across the Great Barrier Reef between 1900 and 2017. Image by Jens Zinke © All Rights Reserved

Collection and Analysis

Two cores were collected from Flinders Reef: a three-meter-long core (FLI01A) was collected in May 1992 from a depth of five to ten meters by divers from the Australian Institute of Marine Science using a hydraulic drill system; and a 0.5-meter-long core (FLI05A) was collected in December 2017 from a depth of five meters by divers from James Cook University (Australia) and the University of Western Australia using a pneumatic air drilling system during a research cruise with MV Phoenix.

Cored samples were sliced into slabs (seven to eight millimeters thick and nine centimeters wide) along the main growth axis, using a diamond-blade precision saw. Slabs were X-rayed to assess the optimal sampling path closest to the main growth axis. Both cores were sampled at bimonthly resolution (six samples per annual growth band) from 1940 to the end of the core, and FLI01A was sampled at annual resolution pre-1940.

The samples were subjected to various analyses, including radiocarbon (carbon-14), isotopes (nitrogen-15, oxygen-18, carbon-13), trace elements (ratios of strontium/calcium, magnesium/calcium, uranium/calcium, and barium/calcium), pollution metals, radiogenic isotopes (plutonium, caesium, and americium), and spheroidal carbonaceous particles (SCPs).4

The Research Team

The Flinders Reef team is headed by Jens Zinke. Arnoud Boom heads the stable isotope lab, Neal Cantin is a research scientist, Nicolas Duprey is the Organic Isotope Geochemistry group leader, Irka Hajdas is head of the carbon-14 lab, Neil Rose and Sarah Roberts are responsible for SCP and caesium/americium analysis, and Andy Cundy and Simon Turner are responsible for plutonium isotope analysis. The extended team includes research technician Grace Frank, emeritus research scientist Janice Lough, and technicians Sue Sampson, Adam Cox, and Genna Tyrell.

The work was supported by the University of Leicester, the Max-Planck Institute for Chemistry, the Australian Institute of Marine Sciences, ETH Zürich, University College London, and the Wolfson Foundation (Royal Society Wolfson Fellowship received by Jens Zinke).

From left to right: Arnoud Boom, Sue Sampson, Genna Tyrell, Adam Cox, and Jens Zinke. Photograph by Kerry Allen © All Rights Reserved

Principal investigator:

Jens Zinke, University of Leicester

Contributing Scientists/Researchers (listed alphabetically):

Molly Agg, University of Leicester, ICP-MS analysis

Arnoud Boom, University of Leicester, Stable isotope analysis

Neal Cantin, Australian Institute of Marine Science, Core collection and analysis

Adam Cox, University of Leicester, ICP-MS analysis

Andy Cundy, University College London, Plutonium isotope analysis

Nicolas Duprey, Max-Planck Institute for Chemistry Mainz, Nitrogen isotope analysis

Grace Frank, Australian Institute of Marine Sciences, Core collection and analysis

Irka Hajdas, ETH Zurich, Radiocarbon analysis

Janice Lough, Australian Institute of Marine Sciences, Core collection and analysis

Alfredo Martinez-Garcia, Max-Planck Institute for Chemistry Mainz, Nitrogen isotope analysis

Sarah Roberts, University College London, SCP analysis

Neil Rose, University College London, SCP analysis

Sue Sampson, University of Leicester, ICP-MS analysis

Genna Tyrell, University of Leicester, Stable isotope analysis

Handong Yang, University College London, 210Pb, 137Cs isotope analysis

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access page (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority website

Calvo, Eva, John F Marshall, Carles Pelejero, Malcolm T McCulloch, Michael K Gagan, and Janice M Lough. 2007. “Interdecadal Climate Variability in the Coral Sea Since 1708 A.D.” Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 248 (1): 190–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.12.003.

Druffel, Ellen R. M, and Sheila Griffin. 1995. “Regional Variability of Surface Ocean Radiocarbon from Southern Great Barrier Reef Corals.” Radiocarbon 37 (2): 517–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033822200031003.

Druffel, Ellen R. M, and Sheila Griffin. 1999. “Variability of Surface Ocean Radiocarbon and Stable Isotopes in the Southwestern Pacific.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 104 (C10): 23607–13. https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JC900212.

Hendy, Erica J, Michael K Gagan, Chantal A Alibert, Malcolm T McCulloch, Janice M Lough, and Peter J Isdale. 2002. “Abrupt Decrease in Tropical Pacific Sea Surface Salinity at End of Little Ice Age.” Science 295 (5559): 1511–14. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1067693.

Pelejero, Caries, Eva Calvo, Malcolm T McCulloch, John F Marshall, Michael K Gagan, Janice M Lough, and Bradley N Opdyke. 2005. “Preindustrial to Modern Interdecadal Variability in Coral Reef pH.” Science 309 (5744): 2204–7. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1113692.

Wu, Yang, Stewart J Fallon, Neal E Cantin, and Janice M Lough. 2021. “Assessing Multiproxy Approaches (Sr/Ca, U/Ca, Li/Mg, and B/Mg) to Reconstruct Sea Surface Temperature from Coral Skeletons Throughout the Great Barrier Reef.” The Science of the Total Environment 786: 147393–147393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147393.