Biotic Change

Arguably the most well-known markers associated with geochronological subdivisions of Phanerozoic time are of biological origin. Body or trace fossils, as well as chemical signatures of life (biomarkers) are commonly used to identify stratigraphic boundaries. A biostratigraphic signature suggestive of anthropogenic impact, however, deals with a constellation of different life-based indicators, primarily human-mediated species extinction, the introduction and dispersal of neobiota, and broader ecological changes measurable in archives of organic matter.

This dossier addresses anthro-biological and techno-ecological signatures as markers manifested in the long-lasting and often irreversible human manipulation of the global biotic environment, considering how they reveal an “Anthropocene biosphere” that differs significantly from the biosphere’s earlier configurations. This new bio-technosphere created by and outliving the humans of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries calls for a new taxonomy and a new aesthetics of the marine and terrestrial spaces that are now being depleted of many lifeforms and repleted with (a few) others, so the dossier advocates.

The megafauna extinction in the Pleistocene, known as the Late Quaternary Extinction, provides the first human-biostratigraphic signal which coincides with growing human populations and their geographical expansion, as well as the development of lithic technologies for hunting and butchering. Although this prominent extinction of large terrestrial mammals was the first hint of a sweeping human alteration of the global biosphere, it was time transgressive, coming in several waves in different parts of the world over about 50,000 years, and thus cannot count as a globally synchronous signal for the beginning of a new geological epoch, not for the Quaternary at least. The current extinction and extirpation pattern, which started in the twentieth century and is showing critical signs of becoming the sixth mass extinction on Earth, is a much more suitable candidate. The overexploitation of marine and terrestrial environments, and especially habitat destruction due to expansive agriculture, has now accelerated the rate of biodiversity loss to unprecedented levels.

Usually, coupled with these extinction processes is the phenomenon of neobiota: species that radiate beyond their pre-anthropogenic geographic range due to deliberate or accidental human introduction. While humans had already begun to translocate animals and plants in the Late Pleistocene, transporting them overseas in the nineteenth century in terrarium-like boxes such as the Wardian case made a substantial difference, both in inter-continental species dispersal and in sheer quantity. In the wake of an accelerated globalized economy in the twentieth century, however, human-mediated biogeographical changes have risen to a new level.

Today, the biotic configuration of certain ecosystems, such as the San Francisco Bay, bears almost no resemblance to that of just a century ago. This new scale of species migration also has severe consequences for human health. The increase of zoonotic diseases, in which viruses jump from animals to humans and vice versa, is one of the consequences of tearing down the geographic barriers between wild animals and humans.

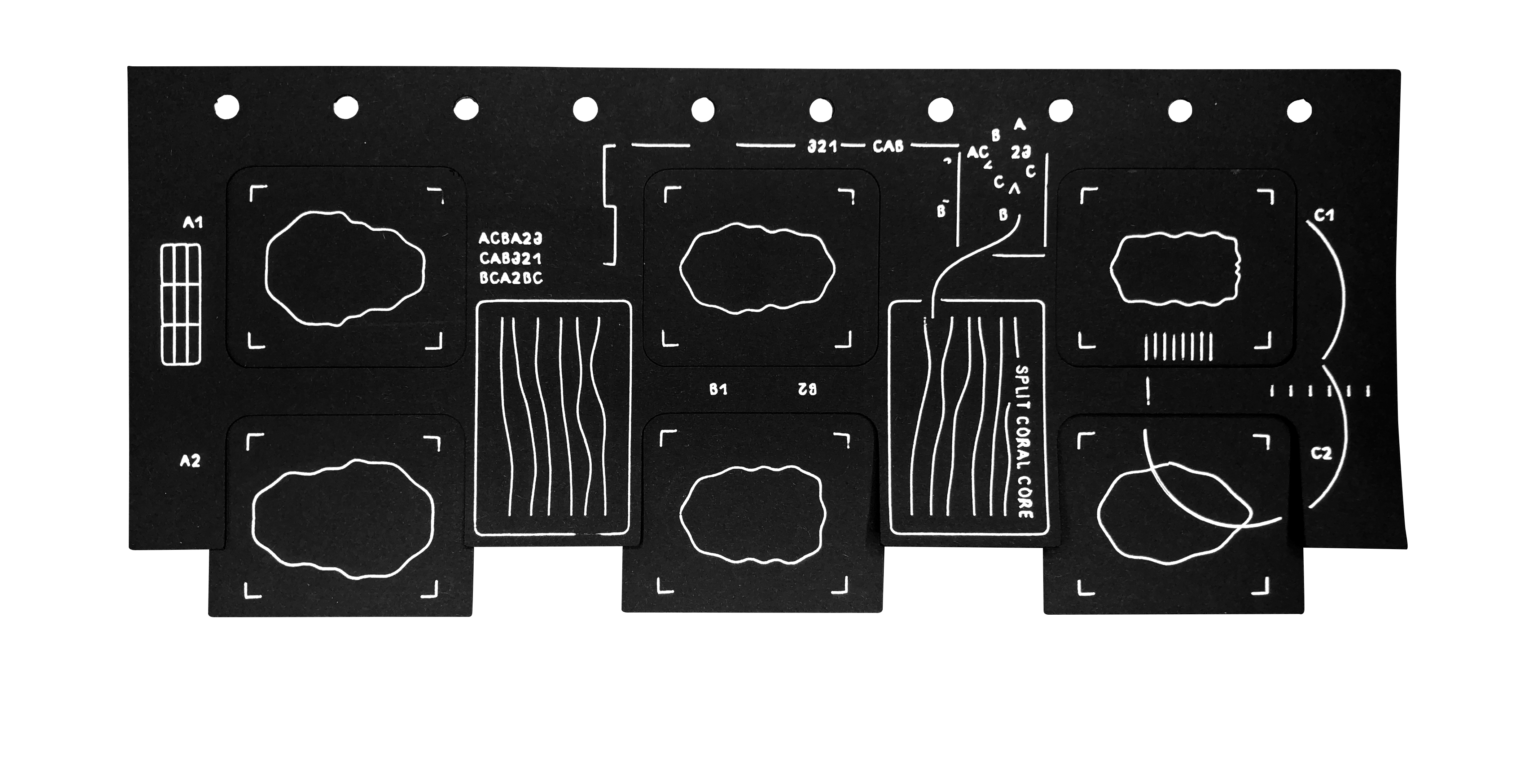

Lastly, a very promising method to define an Anthropocene boundary is the eco-stratigraphic approach, which looks to environmental proxy data retained by specific organisms. Both living and fossil corals and trees, for instance, provide valuable archives of deteriorating ecologies and climate variability. Recording variations in environmental parameters at society-relevant time scales and resolutions is key to understanding the growing anthropogenic pressure that threatens biosphere integrity as a whole.