A Javanese Anthropocene?

Aren’t we overlooking important traditions when we assert the novelty of a geology that deals with human forces? Geographer and writer Adam Bobbette describes the reciprocal and porous relationship between society and geology in early twentieth-century Java, where volcanological activities were seen as a fundamental expression of social history and vice versa.

In a follow-up comment, Japan historian Julia Adeney Thomas points out that the historical and cultural resources that we bring to bear on the unprecedented challenge of the Anthropocene must first recognize our altered reality.

Mount Merapi, 1931. Courtesy Balai Penyelidikan dan Pengembangan Teknologi Kebencanaan Geologi

One of the startling claims of the Anthropocene thesis, for many, is that modern human history is already inscribed in the geological record. This insight—thrilling, even revolutionary for some—suggests a recognition that the boundaries between geology and humans are far more porous than has been conventionally assumed. Defining the beginning of the Anthropocene has resulted in much creative soul-searching in the humanities and Earth sciences. Much of this work has proceeded with the excitement of breaking new ground and opening fresh paths for critical and scholarly reflection on troubling social and environmental questions. The Anthropocene thesis, though, is not actually as new or pathbreaking as many of us have presumed. Dating the Anthropocene, defining its markers and boundaries, and reckoning with what it tells us about human-nature relations has long been a preoccupation of the geological sciences. Since at least the late nineteenth century, geologists have been consistently fascinated with the porous edges between geology and society, and how humans are or are not geological agents. Today’s investigations into the deep methodological quandaries about where and when the Anthropocene began would not have been a surprising pursuit for geologists at the turn of the twentieth century.

It was not only geologists who were preoccupied with these concerns. Many cultures have understood that geological materials are through-and-through social. Volcanoes in central Java in the early twentieth century, for instance, were understood to be social, historical, and political. It was not that social, historical, and political ideas were projected onto geological materials; instead, volcanoes were seen as made up of and expressions of social history. Eruptions and earthquakes were materializations of social processes. When members of the Anthropocene Working Group consider the “material markers” of the Anthropocene as social-historical processes that have transformed natural processes, we should understand that, in early twentieth-century central Java, a volcanic eruption was the effect of historical and social processes intervening in and marking natural processes. This conception of geology did not suddenly disappear with the development of the modern Earth sciences—it was in fact central to the very formation of the Earth sciences in Indonesia and persists there into the present. Today’s practitioners, then, should see the Anthropocene thesis as a continuation of these much longer, often forgotten and overlooked, traditions. That is what this paper is about.

On February 8, 1921, the eighth sultan of Yogyakarta, in central Java, ascended to the throne. Like the sultans before him, his coronation was a spectacular affair. He received blessings from the colonial Dutch governors, and they ate and drank in the palace. Guns were fired from the palace grounds, and, in response, cannons boomed back from nearly 400 kilometers away, near Batavia. Processions with parasols, gongs, crashing cymbals, and ornate clothing circled the palace for curious onlookers. What was remarkable about the event was not just the pomp but its supernatural dimension. In the following days, the sultan’s retinue began to notify the local ruling deities of his ascension. While the sultan had received the blessing of Allah to take up the throne, he was nevertheless obliged to provide gifts to goddesses, ancestral spirits, and demiurges in nearby volcanoes, rivers, forests, and the ocean. The reality, for the sultan, was that his sovereignty was granted by these deities. Moreover, the deities not only lived in the landscape, as if it were a shell—they animated it; they were what would conventionally be understood as life. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, rains, floods, and tsunamis were the voices of the deities. To take up his position, the sultan had to acknowledge that his political power was something given by the deities, and, therefore, that it could also be taken away.

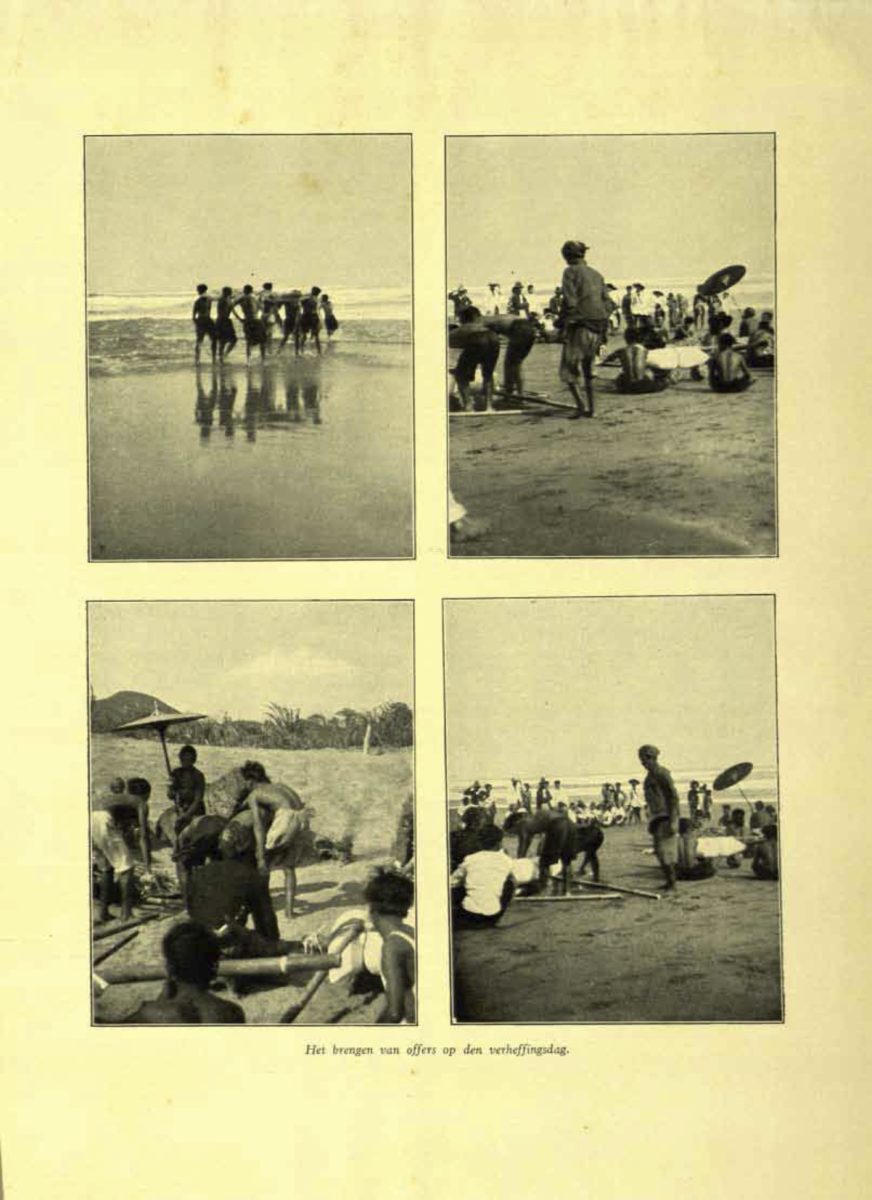

The first place the sultan’s retinue visited was a beach thirty kilometers south of the palace. There, offerings were prepared for Nyai Ratu Kidul, the goddess of the Indian Ocean. The men launched a bamboo raft into the rough waves and watched as it floated into the distance, pulled toward the home of the goddess (see below). The offerings included nail and hair clippings from the sultan, coins, incense, perfumes, and clothing printed with patterns that represented the sultanate. The clothes, some commentators suggested, meant that the goddess could not only take on human form but don the attire of a subject of the sultanate and participate in its social life. She could use the coins at the market and smell like a Javanese aristocrat. It was understood, too, that the goddess was married to the sultan; she visited him in the bedroom he had specially designed for her. With such offerings, given annually, Nyai Ratu Kidul was guaranteed a smooth transition between the human realm and her watery, spiritual home.

Central Javanese court chronicles and literature from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries reported that the very origins of the sultanate relied on Nyai Ratu Kidul’s assistance. The Babad Tanah Jawi: Mulai dari Nabi Adam Sampai Tahun 1647 explains that Panembahan Senopati, the founder of one of the early Islamic kingdoms in Java in the fifteenth century, slept with the goddess, and she agreed to counsel him and his descendants.1 She thus became part of the genealogy of the kingdom, part human, part nonhuman chthonic kin: the sultan was married to the ocean, and his power relied on its consent. Provisioning yearly offerings perpetuated the genealogy.

Newcomers also recognized the significance of Nyai Ratu Kidul. The Dutch colonial geographer Pieter Veth, in his comprehensive 1882 geography of Java, Java: Geography, Ethnology, History, wrote that the Indian Ocean is “bounded by the vast territory of Ratu Kidul.”2 He recorded, too, that all along the southern coast were caves and sacred sites where offerings were given and meetings held with her. Gifts to Nyai Ratu Kidul have been recorded since at least the eighteenth century, but likely have gone on for much longer. M. C. Ricklefs, a historian of Java, thought the goddess was an early modern, or perhaps even more ancient, deity from the Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms.3 While her history remains disputed, it is certain that since the eighteenth century, Muslim revolutionaries, scholars, and mystics have all sought her assistance for their worldly endeavors.

This is, perhaps, no surprise. The Indian Ocean along the south coast of Java is a powerful force. The strong waves make it a difficult landing spot, and it stands in stark contrast to the well-trafficked northern coast that has, for millennia, been a space for cosmopolitan encounters between Java and the rest of the world. The south, however, is subject to tsunamis, earthquakes, and punishing tidal action. It was long understood that enlisting the support of Nyai Ratu Kidul meant becoming the beneficiary of her powers; and so, earthly power rested on natural powers.

After the retinue of the eighth sultan gave its offerings, the emissaries then turned northward, toward the region’s volcanoes. They took the train part of the way, then walked the rest. It was not only the support of Nyai Ratu Kidul they needed but also that of the inland deities. Traveling to Merapi, the volcano at the northern edge of the kingdom, they gave offerings to a pantheon of ancestral spirits. Some of those were friends of Nyai Ratu Kidul and connected the volcano to the ocean. Other deities were descendants from the earliest history of Islam in Java. Still others were even older and descended from the Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms in the region. Kyai Empu Permadi, for instance, was a deity derived in part from the stories of the Mahabharata but who later acquired the title “kyai,” indicating that he attained the status of a Muslim scholar. The volcano, therefore, was conceived of as social, political, and historical; it was social history materialized. It also was not separated from the Indian Ocean and its queen: she was noted to frequently travel along the rivers to the crater. Additionally, when Senopati first sought the assistance of the goddess, several stories explained that his trusted confidant Kali Jaga (who may have been a Dutch colonial administrator) went to the volcano to become a deity.4

One way to think about what all this adds up to is as a form of animism, because it ascribes human properties to nature. But a more productive way to conceive of this system of thought is that it anticipates the core insights of the Anthropocene. The offerings of the sultans of Yogyakarta to ocean and volcano deities acknowledged that society and nature—and more specifically, society and geology—could not be separated. Put another way: sovereigns (and their subjects) were geological. In central Java, this fact was recognizable in geological processes. They did not think that society was projected onto geology merely as an idea or a story but rather understood that society could be identified, was legible, in geological processes. This is also a central idea for today’s thinkers grappling with the Anthropocene: society is again coming to be seen as recognizable in the geological record. Javanese society has been wrestling with the consequences of this very same realization since at least the eighteenth century.

What was important for the Javanese worldview was understanding that human social and political orders had to enter into alliances with geological processes that created debts. Society was not a given, nor was it created through the control or submission of nature, nor did it emerge and then become autonomous from a state of nature. Society and geology required two-way exchanges. In central Java, it was even acknowledged that society came into being through the consent of geological forces; provisioning offerings was to ask for the consent of geological processes to form a political body—a society. In other words, politics was not the management and negotiation of a social contract; rather, it was a natural contract between a social order and geology. Giving food, clothing, tobacco, and other ostensibly human objects was not a signal that the Javanese thought the sea and volcanoes were just like us; it was rather a gesture to maintain the lines of circulation between the ocean, volcanoes, and sultanate.

I must emphasize that what I am describing here is not some faraway, sheltered society of interest mainly to anthropologists. What I am describing is a thoroughly modern, cosmopolitan conception of geological processes, and one that has been fully integrated into modern geological sciences. Alongside Dutch colonial aristocrats, Sanskritists, ethnologists, geologists, and mining engineers, Javanese aristocrats and intellectuals were fascinated by the political and spiritual geography of central Java. The eighth sultan’s successor, Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX—who likewise slept with and gave offerings to the goddess of the Indian Ocean as part of his royal duties—studied Indology (the study of history, cultures, and languages for the purpose of colonial administration) in Leiden before taking up the sultanship. In 1933, the coronation of the eighth sultan of Yogyakarta recounted above was described in the journal Djåwå, an organ of the Java Institute dedicated to documenting Javanese courtly life, traditions, and literature.5 Its pages frequently featured accounts of the spiritual geography of central Java, its histories, and its relationship to politics. Lucien Adam, for instance, who was a colonial administrator in Yogyakarta in 1928, wrote academic articles on the spiritual topography and toponymy of the Javanese countryside. The political geology of central Java, in other words, was intensely interesting to, and almost obsessively documented by, colonists and Javanese alike. Scientists were also fascinated. When geologists undertook fieldwork on the numerous volcanoes in the region, they recorded in their field reports the sites where ritual offerings occurred. Georges Kemmerling, the first head of the Netherlands East Indies Volcanological Survey, recorded that during his fieldwork on Merapi and Agung in Bali, he frequently followed ritual paths to sacred sites. Scientists were not just aware of, they were fascinated by, the spiritual world of lively geologies and oceans in which they were operating.

And, as previously mentioned, the geospiritual Javanese world went on to shape the modern Earth sciences. It was on those same ritual pathways that colonial scientists in the 1920s and 1930s first studied the craters and calderas of Java’s volcanoes. Javanese laborers and porters who accompanied the scientists and conducted scientific labor for them also taught them the traditional names and genealogies of sacred sites, which the scientists then included as toponyms in their scientific surveys. The first scientific volcano observatories were often built on or near to sacred hills and promontories, because they afforded the best views of calderas. As part of their research, scientists used accounts from literature produced in the sultanates—the same literature that explained the genealogies of deities—to reconstruct ancient natural disasters, including floods, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions. What is today often described as myth was, in fact, the foundation for modern scientific natural histories. Colonial scientific knowledge (though the scientists themselves were not always aware of it) was enabled and shaped by the spiritual geographies that preceded their arrival to central Java.

Mount Merapi, 1930. Courtesy Balai Penyelidikan dan Pengembangan Teknologi Kebencanaan Geologi, © All rights reserved Balai Penyelidikan dan Pengembangan Teknologi Kebencanaan Geologi

Legacies of Javanese Political Geology

The legacy of Javanese political geology since the 1920s is a fraught one. The Labuhan ritual, in which offerings are given to deities, has, by most accounts, continued without interruption. The sultan-appointed custodian who gives the offerings to Merapi today, for instance, is a descendant of the custodian who provided the offerings for the ninth sultan. The pantheon of deities, though, has changed. During the military dictatorship of Suharto, between 1966 and 1998, it is said that sacred sites on the volcano became the abode of persecuted communists. Suharto came to power and sanctioned the mass murder of hundreds of thousands, perhaps up to one million, affiliates of the Indonesian Communist Party and even styled himself after a central Javanese sultan and a military general. He was also known to give offerings to Nyai Ratu Kidul. Tabloid magazines in the 1990s reported that an eruption on Mount Kelud was a signal that Suharto would save the population as a mythical righteous king before the apocalypse. There is nothing inherent in the political geology of Java to prevent it from becoming a kind of totalitarian animism.

The current sultan of Yogyakarta no longer partakes in the rituals; he is a capitalist who has used his power to pursue the development of the flanks of Merapi with shopping malls, hotels, and golf courses. He is often silent on the spiritual geographies of the sultanate. When he has addressed rituals and traditions, it has been to acknowledge them as cultural heritage to help promote the tourist industry. Ceremonies such as the Labuhan have, as a result, taken on the tenor of a spectacle for media consumption.

The relationship between Javanese spiritual geographies and the environmental sciences has become no less fraught. In the past thirty years, there has been no shortage of snide dismissals of rituals by local and international scientists, brushing them aside as belonging to a backward peasant attitude. Alternatively, researchers have condescendingly tolerated them as superstitious traditions, unproblematic unless they begin to intervene in their serious scientific work. In many of these conflicts, Earth scientists working on behalf of the Indonesian state have held the quintessentially modern view that traditional culture is one of many belief systems projected onto nature, whereas science, by contrast, understands nature in and of itself. In this schema, there is one nature and multiple cultures.

Yet, the more interesting results have arisen where Earth scientists have not set themselves in opposition to Javanese spiritual geographies. In 2016, Surono, a seismologist and likely the most famous scientist in Indonesia, joined the Labuhan ritual on Merapi the day after the offerings had been given to the goddess of the Indian Ocean. His appearance there was a media event, with crowds eager to take a selfie with him. Surono stated, in an interview with the national magazine Tempo, that it is necessary to give offerings to the Earth to remind ourselves that humans are not in control of nature. Modern science, he cautioned, can create a false sense of certainty. He also warned against the perilous rise of socially conservative Islam among Indonesia’s more than 200 million Muslims. Strictly monotheist forms of Islam reject the giving of offerings as a form of idolatry. For Surono, this form of monotheism goes hand in hand with the desire to control nature. Partaking in the giving of offerings to Nyai Ratu Kidul was thus, for Surono, a form of political protest—an intervention in both the Earth sciences and religion.

Paying attention to histories of Javanese spiritual geographies reminds us that the very problem at the heart of the Anthropocene debate is much older than is commonly recognized. On the slopes of Java’s volcanoes and on its shorelines, sultans, scientists, mystics, and scholars have long been wrestling with this very problem of how geology is social. When Javanese sultans felt the rumblings of a volcanic eruption, they acknowledged that it could not be understood separately from their power. Earthquakes did not just happen to society from the outside: they were materializations of social processes. To give offerings to volcano deities, then, was to acknowledge a debt to those deities, for they fully participated in social existence. It may be that this perspective is more the norm than the exception in human culture. It is perhaps only a very recent invention, by troubled societies, to believe the opposite. The Anthropocene, in this regard, does not mark an exceptional event in modern history but rather is an acknowledgment of a much older insight. By turning to traditions such as Javanese geological thought, those of us who are only now realizing that we live in the Anthropocene can begin to learn how to live geologically, once again.

COMMENTS ON ADAM BOBBETTE’S “A JAVANESE ANTHROPOCENE”

It’s an enormous pleasure to comment on Adam Bobbette’s delightful paper. Adam and I are both scholars of Asia, “Asia” being an inept category encompassing a vast diversity of cultures and landscapes. In one sense, “my” Japan and “Adam’s” Java are so different as to render this category meaningless. Japan can claim to have had a fairly continuous centralized state since around 500 CE and the oldest imperial lineage on the planet, while the political configurations of Indonesia and one of its main islands, Java, coalesce, flicker, and fold through the centuries. The political entity central to Adama’s story, the Sultanate of Mataram in Yogyakarta, flourished from only the late sixteenth century. While Japan was able to resist Western colonial domination, Java succumbed to the Dutch East India Company. While Japanese thought draws on Confucianism and Taoism, Javanese ideas are informed by Hinduism and Islam. To say that “Asia” encompasses them both just shows how important it is to make sure we understand the concepts that we use.

And yet much of what Adam describes about the relationship between society and geology in Java is familiar from my study of Japan. In Japan, too, there has long been a sense of the power of geological forces in politics, and the need for an alliance between Earth and empire, nature and rulers. Adam speaks of the sultan’s relationships with the goddess of the Indian Ocean, Ratu Kidul, and with the deity of the volcanic Mount Merapi. In Japan, the most politically important deity is Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess, with whom the emperor spends the night in her shrine at Ise as part of his coronation ceremonies. This Sun Goddess has a vast number of relatives, eight million by traditional count, all of whom are constitutive of Japanese identity, landscape, and polity. It is, however, the emperor’s ancestral decent from Amaterasu, and the imperial line’s continued congress with her, that has secured his family’s place on the throne if not since 660 BCE (as sometimes claimed) at least for 1,500 years.

Nor is that all. In Japan, as in Java, geological forces provide running commentary on politics. Neo-Confucianism suggested that earthquakes and other natural disasters are indications of rulership gone wrong. Since Japan has more earthquakes than any other place on Earth, and since earthquakes have caused frequent, terrible fires in Japan’s wood-built cities, rulers took geology’s criticisms seriously. One way of handling these marks of displeasure was to start time all over again. With the beginning of each imperial reign, the year would revert to one—but sometimes, in response to disaster, the year reverted to one in the middle of a reign, giving a fresh start, a new beginning to time itself. Another geological formation, Mount Fuji, is an internationally recognized symbol of Japan. So I am entirely convinced by Adam Bobbette’s portrait of the Sultanate of Yogyakarta as a political entity in alliance with geology—in a real, serious, and foundational way.

But what about the bigger claim in this paper that the Javanese approach to geology illuminates the Anthropocene? Adam argues that in recognizing their geological relationship, the Javanese recognized the Anthropocene, and therefore that “the Anthropocene thesis” is not unprecedented and new. This claim rests on two propositions about this new epoch:

- that the Anthropocene’s novelty lies in proposing that geology matters to human societies

- that the relationship being proposed is one of reciprocal alliance.

Neither, it seems to me, is correct.

Human societies have always interacted with their environments, including geology, and could not have survived otherwise. As biological agents, we have always had reciprocal relations with other organisms around us, eating and being eaten, by everything from mammals to microbes, from fish to fungi. As chemical, physical, and geological agents, we have always interacted with the non-organic elements as well, partly mediated through these organic exchanges. For instance, we eat plants nourished by soil created by geological forces. We have moved rocks, chipped away at stones, damned streams, scraped soils, and a host of other geological activities for as long as we’ve been around. And many societies, like Java and Japan, have told stories about their relationships with geological forms and substances. Geological relationships whether recognized as in Java and Japan or unrecognized are foundational to human societies, and always have been.

What is new in the proposition of the Anthropocene is not that geology matters to human societies. Instead, what is new is the Anthropocene is that the collective human impact has left a near-synchronous global marker in the Earth’s crust, making us a chronostratigraphic force, and that our activities have transformed the way the planet functions. There was a time—before the mid-twentieth century Great Acceleration—when humans did not impact the Earth System but instead altered local, regional, and even global systems, but not enough to alter the way the planet as a whole functions. What distinguishes the Anthropocene is that human activities have altered the Earth System. This is the crucial difference between “Anthropocenic change” to our planet and “anthropogenic changes” to the environment

In other words, I fully agree with Adam’s claim that the social is geological. But what is new in the Anthropocene is that the social is now chronostratigraphic, having overwhelmed the Holocene Earth System.

Secondly, this new relationship between societies and the Earth is not best characterized as a “reciprocal alliance.” Earth’s Holocene functioning has been so dominated by collective human impacts that “conquest” or “domination” are better terms. As the title of a now famous 2007 article by Will Steffen put it, humans are “overwhelming the great forces of nature.” Take lithography. The roughly 5000 natural minerals are now wildly outnumbered by the more than 193,000 human-made “inorganic crystalline compounds,” or what you and I might call “rocks.” More than 8.3 billion tons of plastics coat the land, water, and our internal organs, and plastic now outweighs all living mammals. At least three-quarters of Earth’s land surface has been altered by humans for our own uses, pushing out other species. This relationship is not an alliance, and the forces creating it are not reciprocal.

So, I am not convinced that the ritual practices of the Sultanate of Yogaykarta (or the Emperor of Japan) prefigure the Anthropocene proposal of the AWG or the current understanding of Earth System science. Similar stories in which geological or geomorphological formations resonate with cultural forms are found in every corner of the world, from Europe to South America, Australia to Siberia. One might mention Aboriginal rock art from at least 30,000 years ago; the elaborately carved limestone complex known as Göbekli Tepe in Southeastern Anatolia built between c. 9500 and 8000 BCE; the astronomical clock of Stonehenge; the ancient Mayan view of cenotes (natural sinkholes) as sacred; and much more. All are interesting; none bear any relation to the Anthropocene. However, what geological consciousness in these earlier societies represents and—importantly so—is a recognition that human well-being cannot be divorced from Earth. Those like the Eco-Modernists who trumpet a “dematerialized” economy that would transcend the Goddess of the Indian Ocean and the Deity of Mount Merapi tempt the wrath of deities. And they court the dangers of a destabilized planet. It is far better to work toward a new alliance between ourselves and our dramatically altered planet.

Adam Bobbette is a Lecturer at the University of Glasgow, School of Geographical and Earth Sciences. His books include The Pulse of the Earth: Political Geology in Java; with Alison Bashford and Emily Kern, New Earth Histories; with Amy Donovan, Political Geology: Active Stratigraphies and the Making of Life.

Julia Adeney Thomas is Associate Professor at the University of Notre Dame focusing on the intellectual history of Japan and the Anthropocene.

Please cite as: Bobette, A and J A Thomas (2022) A Javanese Anthropocene? In: Rosol C and Rispoli G (eds) Anthropogenic Markers: Stratigraphy and Context, Anthropocene Curriculum. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. DOI: 10.58049/ypyz-5f29