Whale Falls, Carbon Sinks

Aesthetics and the Anthropocene

The following essay and mapping exercise emerge from the conversations and visual research of the Carbon Aesthetics group, which consists of artists and scholars exploring carbon and its relations in the artistic research project of the “Carbon Catalogue.” Focusing on whales—and the way whales are considered as an environmental archive and “no-tech” carbon storage by marine biologists and sustainability economists alike—the group reflects on the natural-cultural history of these creatures whose non-human bodies allow for thinking across different aesthetic and epistemic registers.

Following the essay is a reflection by Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent on how carbon’s ubiquity, connectivity, and scalability allow its aesthetics to open up a new way of “being in-the-world.”

Dear reader, for the best experience of this contribution, please play the following audio recording as you read.

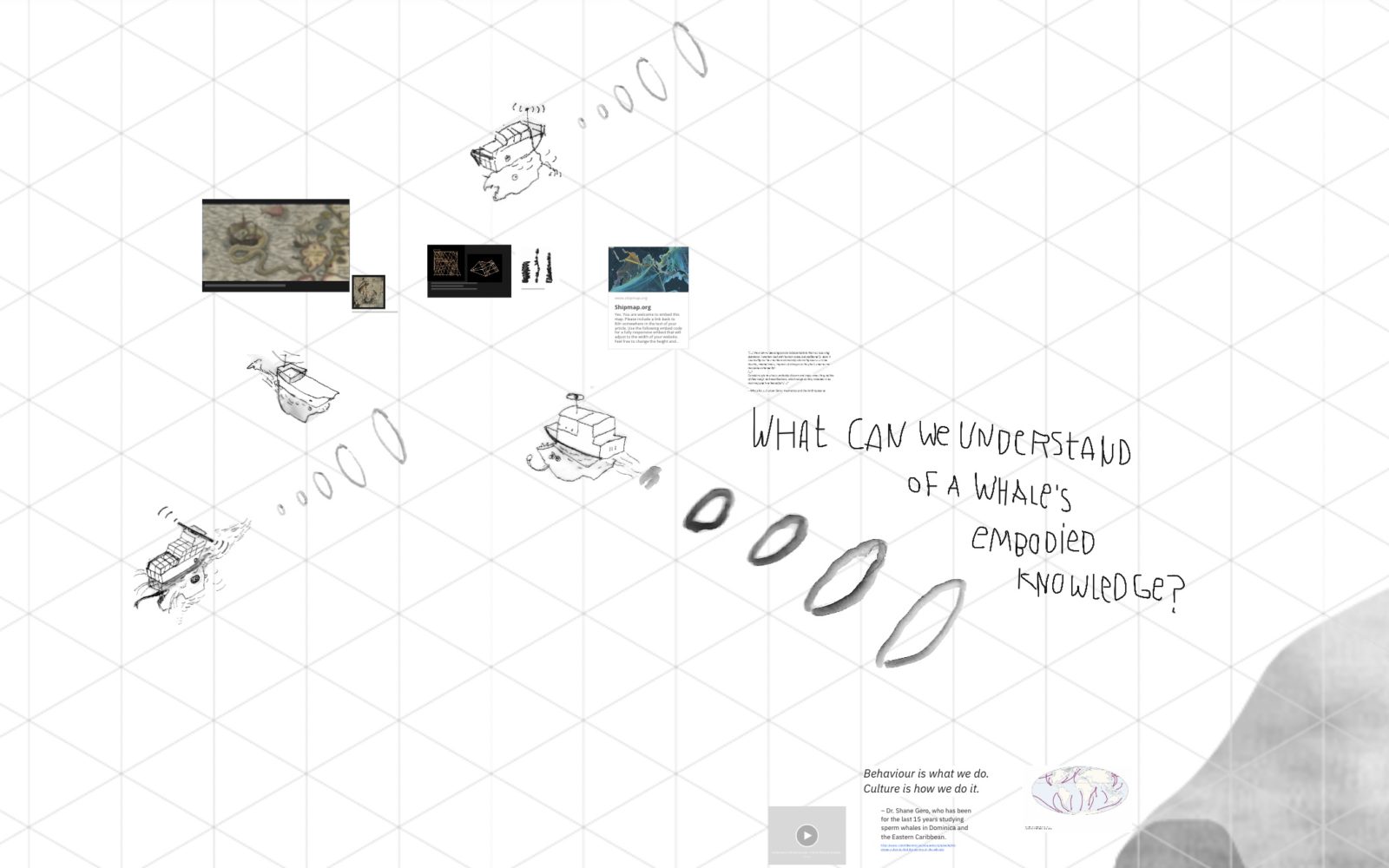

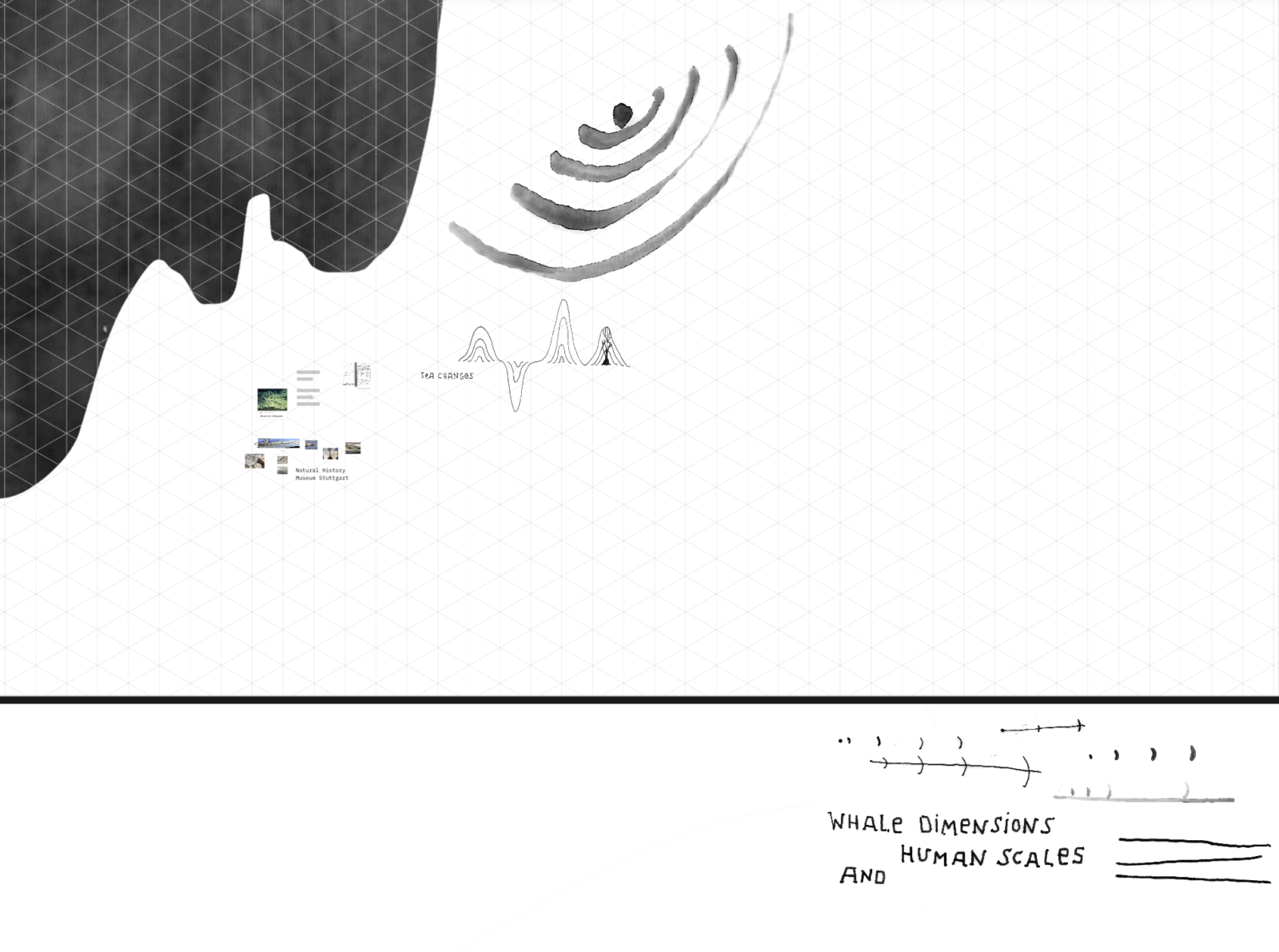

Inspired by Myriel Milicevic’s proposed research project on whales, the Carbon Aesthetics group positions whales as “boundary objects” that lay the foundations for a multi-disciplinary, non-anthropocentric encounter with the world. In this encounter, human energy use, chemical histories, global economies, and processes of combustion can be considered in a way that centers a non-human body or bodies. The group’s discussions brought together a broad spectrum of ideas, ranging from Milicevic’s interest in studies that frame whales as carbon sinks and the challenges of representing non-human perspectives, to Toland’s coming to terms with the legacies of whaling histories in her hometown of Boston and neighboring New Bedford and Cape Cod, Winkler’s suggestion of burning as relationality, Burbano’s experience of whale watching on the Pacific coast of Colombia, Foerster’s focus on aesthetics as aisthesis, and Sobecka’s interest in the place of whales in circulations of matter and as imaginaries. Visual and auditory references were collected iteratively on a Miro board that charts the dimensions of whales in vast ocean space and time spans that are impossible to compare to human scales. Accompanied by this chart, the following text is a reflection on what we can learn from whales about “Carbon Aesthetics” as a more-than-human marker of the Anthropocene.

Valuing whales

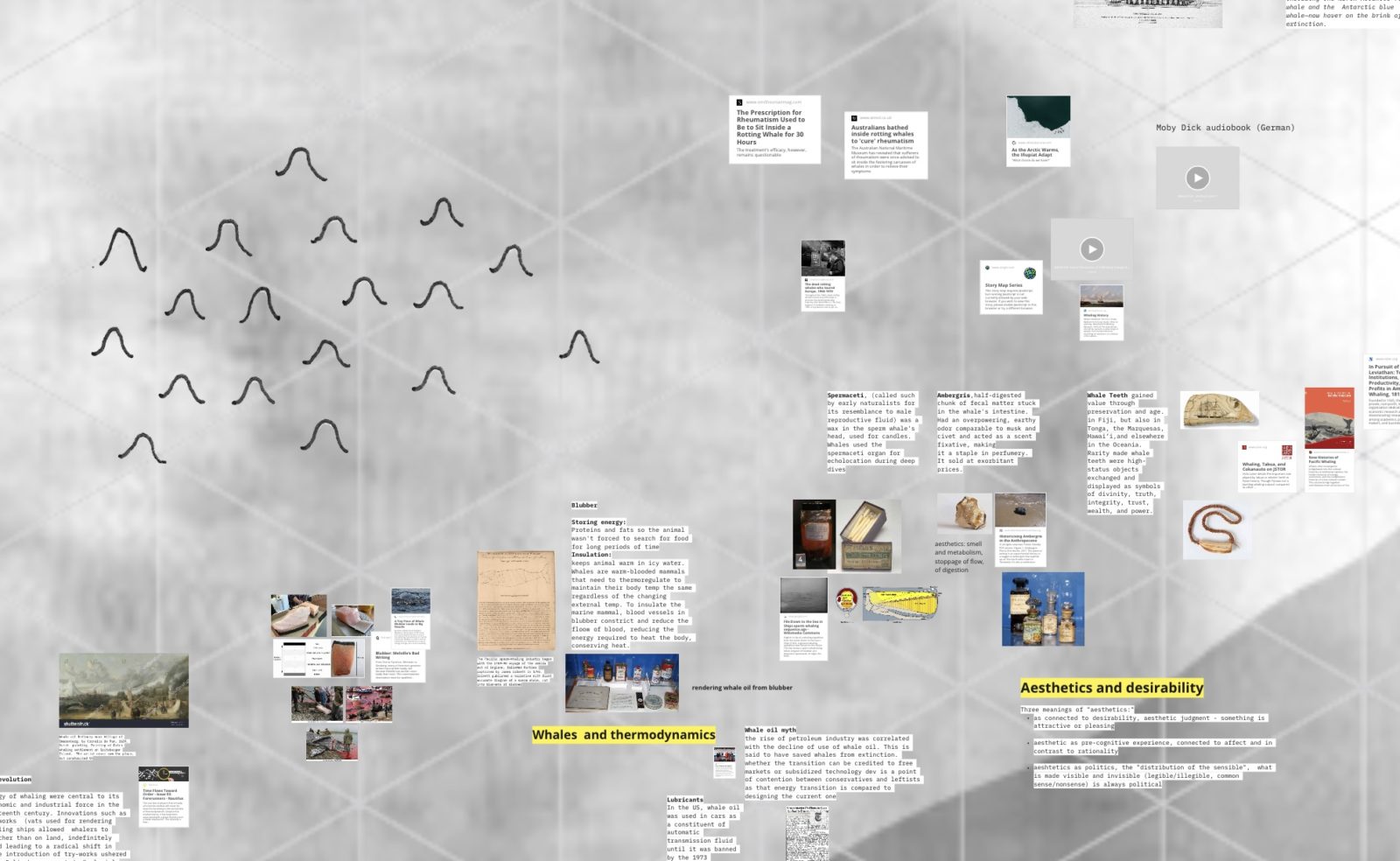

In 2019, economists at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) calculated that whales, when considered a carbon sink, are an ecosystem service which may be worth millions of dollars per whale.1 A few years earlier, a number of new studies showed the harmful effects of noise pollution on these marine animals.2 Each approach sees the whale through a different set of material relations in which it is embedded: one is economic and calculative, and the other sensory, aesthetic, and affective. In the Anthropogenic Markers project the chemical signatures of large-scale processes play a determining role in marking the Age of Humans. The protocols of stratigraphic classification, which make particular chemical histories not only visible but authoritative in categorical designation, prompted our consideration of which socio-material relations with chemicals are rendered visible and operational through various processes of techno-sciences. These processes have been called the everyday politics of aesthetics, which operate beyond the divide between the sensuous and the intelligible.3 They have driven the knowledge practices and sensibilities made manifest in everyday products and lifestyles—from scrimshaw snuffboxes to twitter “fail whales”—that span centuries of consumer behavior and have an impact not only on the individual psyche but on social relationships driven by what Gernot Böhme describes as “aesthetic capitalism.”4 Understanding these processes as generative of a certain “regime of visibility” or a certain aesthetic allows us to consider how they shape environmental realities. It invites us to ask, as Nicolas Shapiro and Eben Kirksey write, what the infrastructures are that generate environmental constructs, that can perpetuate environmentally embedded violence, and where the risks of reproducing them or the opportunities of countering them lie.5 When our chemical co-existences are always mediated, what role can aesthetics in the sense of aisthesis, or sense perception, play in aesthetics as a mode of performing politics? What role can it play in influencing value assessments of more-than-human lives such as our mammalian relatives in oceans deep? As Birgit Schneider suggests, perhaps a path to action must be led via aesthetics.6

to Miro board All images by the Carbon Aesthetics working group, © All rights reserved the Carbon Aesthetics working group

The point of departure for this contribution are studies that consider whale bodies as an environmental archive, containing many of the material markers that signal the onset of the proposed new epoch of the Anthropocene and in particular chemical markers of fossil fuel combustion. Given that at least fifteen cetaceans species are listed by the IUCN as critically endangered, over the future of whales looms another possible marker of Anthropocene—species extinction. But it’s not only the presence of material markers that led the group to focus on whales. Choosing whales centers a non-human being, and invites a closer consideration of exactly how whales and their material relations are invisible. What registers of perceptions and sensitivities would enable understanding of material relations in which it and us are embedded together in a way that would foreground and reorient unrecognized connections, concerns, and values?

Sensing whaling

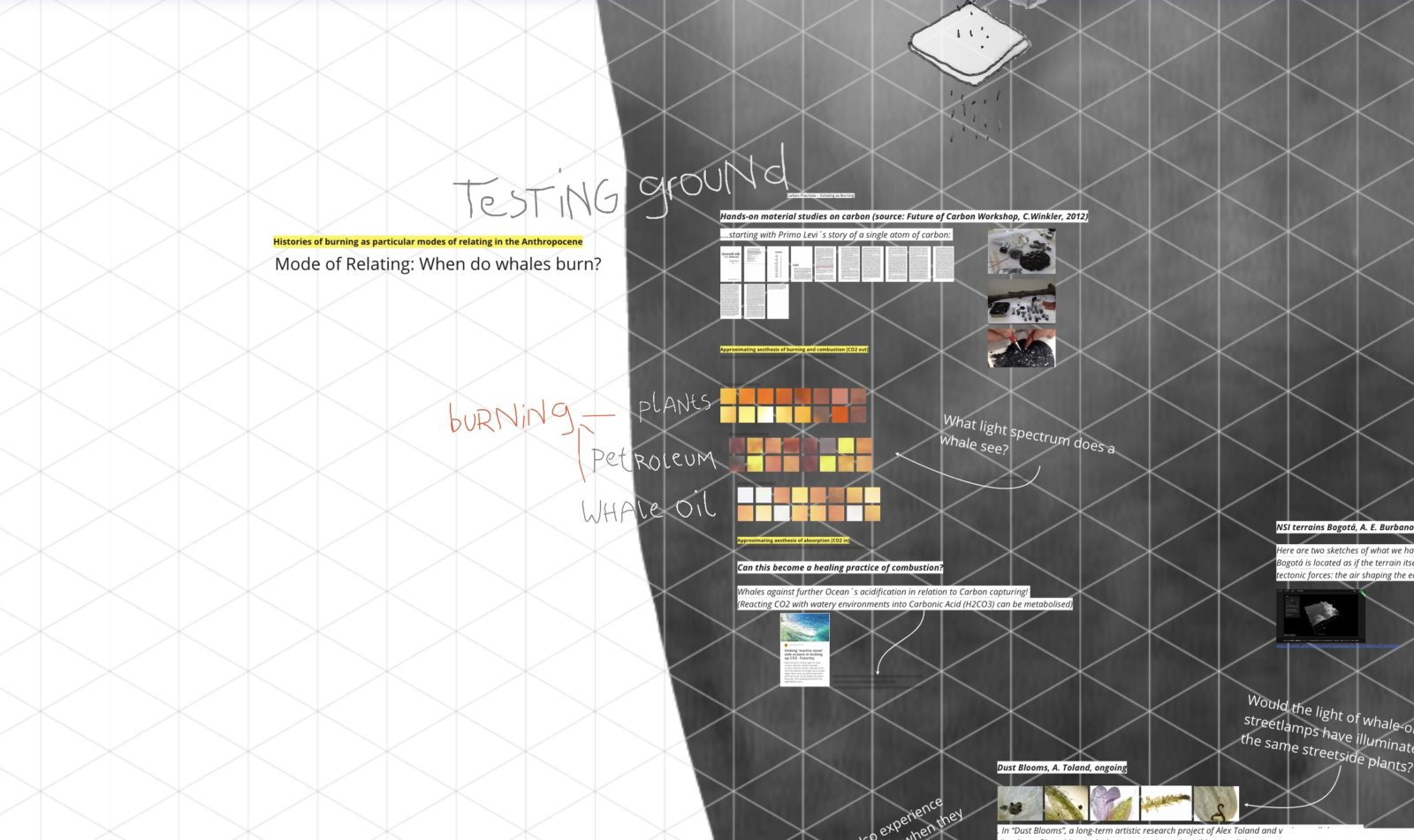

Following the different interconnections that have been shown between whales and their ecosystems, we inevitably retrace the paths forged by the human knowledge practices that produced and privileged a particular mode of relating, the very mode which set in motion many of the “accelerators” of Anthropocene processes. The human pursuit and transformation of environments for economic productivity became disastrously linked with a number of whale species, from the emergence of industrial whaling in the seventeenth century, to 1986, when the International Whaling Commission (IWC) banned commercial whaling throughout the world. While the practice of whaling is documented to be at least 8,000 years old, the large-scale “harvesting” or “mining” of whale bodies for fuel is, like so many other aspects of the Anthropocene, inherently linked to processes of imperial colonialization and industrialization. Whale oil and spermaceti, the energy sources derived from whale tissues, were used primarily for lighting, for producing an ambiance, an environmental condition which enabled the production of knowledge and subsequent industrial development.7 Burning of whale oil advanced humanity on the closely entangled paths of illumination, productivity, carbon fuels, and combustion.

After spermaceti was first used to make candles in the mid-eighteenth century, the lucrative potential of whale-based illumination products was quickly recognized and spurred a long-lasting, immensely profitable, and politically-influential whaling industry. Only after more than a hundred years of dominance did whale oil start to be replaced in the late nineteenth century by kerosene, or “coal oil,” invented in 1846 by the Nova Scotian physician and geologist Abraham Gesner. The subsequent energy transition happened fast, propelled by a number of factors. Whaling was in decline, as whales had already been hunted to near-extinction and hunting vessels had to make longer and more risky voyages to find them. Whale products shot up in price, while petroleum, one of the sources for kerosene, was cheap to produce. In addition, petroleum was becoming a material feedstock which found its way into a new consumer society in a variety of uses other than lighting. More complex refineries invented new technologies and products that served the new consumers.8 Ultimately, in a tossup between kerosene and whale oil light, the quality of kerosene light became decisive for its adoption: kerosene burned cleaner and more brightly. Even lighthouse keepers, loyal holdouts to the whale oil industry, had to convert to kerosene when ship captains complained about the inferiority of the whale oil lighthouses.9 As European seafarers favored the light that shone most brightly, whale populations were inadvertently enabled to survive, even though their numbers remain critically low.

Lighthouses, these remote points of light signaling the furthest reaches of European exploits, guided the vessels and the processes of globalization in the nineteenth century, beguiling voyages of colonial expansion, trade, and migration. As the paths for exploration, extraction, and production were revealed and forged by literal and metaphorical processes of illumination—where artificial light and knowledge practices made the Earth ever more visible and better articulated as a resource—vision and its way of seeing carbon were aligned to make the earth’s matter productive. With the availability of artificial light powered by carbon fuels, vision was further privileged as a mode of sensing; in turn, vision privileged carbon as an object of sensing, sustaining a feedback loop of visibility, power, and aesthetics.

The same blubber that whales were hunted for today proves valuable for creating another kind of visibility, extracting Anthropocene-marker relevant data. Fatty tissues act as natural sinks for lipophilic compounds, such as historic-use pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), methyl mercury, or hormones. The analysis of the Carbon-13 (δ13C) isotope, for example, in whales’ ear plugs and fatty tissues, shows with a six-month resolution the so-called Suess effect, the chemical signature of increasing levels of anthropogenic fossil-fuel combustion over time.10 Analyzing the tissues of multiple whales reveals a long time-series that crosses the potential threshold of the Anthropocene, proposed to be around the 1950s. Whale bodies are high temporal resolution archives of other chemical histories as well. The time-series of these chemical signals have been used to reconstruct past ecosystems, and histories of how whale individuals and populations responded to the environmental stress factors and other impacts caused by anthropogenic activities—including the whaling industry, noise pollution, war, transport, and the leisure industry, and more recently, plastic pollution and ocean acidification.11 We argue that those chemical signatures can serve not only as an analytical tool, but also as a mode of relating—to whales, and more broadly to other entities and processes of Anthropocene, if we make sense of them through affect and aesthetics. What might it mean to become sensitive to the broader range of material relations in which whales are embedded, rather than seeing only the relations which continue to cast the whales, along with other creatures and environments, as a resource?

We are inspired by the aesthetics that emerge from marine ecologists’ descriptions of the horizontal and vertical translocation of nutrients in the oceans by whales as “whale pumps,” “whale conveyor belts,” and “whale falls.”12 The throngs of phytoplankton, thriving on whale excrement deposited at the ocean’s surface, or the benthic invertebrates, feeding on dead whale bodies fallen to the ocean floor can hardly be described as “consumers”. Economic metaphors fall far short of the richness of mutualistic entanglements within networks of biogeochemical relationships and flows. Scientists react with lack of words and expressions of wonder to the ecological complexity revealed in events such as “whale falls” (sinking of a whale carcass that provides a sudden, concentrated food source and a bonanza for organisms in the deep sea).13 Witnessing scientists’ grasping at strange metaphors to describe it makes it very clear that there’s always more going on than what can be comprehended with reason and language, and certainly more than what can be captured in abstractions of markets and quantified exchanges. Whale falls rip holes in such constructed realities presenting an image of nature that transcends any hard lines humans draw between species, generations, life and nonlife, or producers and consumers. As such whale falls presents an opportunity to invent a new language, new speculations and stories, to ask new questions.

Artistic practices

The large-scale material transformations discernible in geological and ecological data that might come to mark the start of the Anthropocene also make the Anthropocene feel, smell, taste, and look a certain way. In other words, material impacts, even at a planetary scale, are discernible through aesthetic registers. To make sense of the Anthropocene through these registers would call for a mode of encountering the world through the dimension of affect rather than cognition, experience rather than representation, sense rather than significance. For example, we can ask, if perhaps speculatively: how does a marine mammal experience ocean acidification? Is it felt in the hunger, malnutrition, or stress related to the disappearance of their food sources? Can the softening of shells and skeletons of whale prey be detected through mouthfeel (or for our purposes here, baleenfeel)? We know whale song can become indiscernible across long distances in waters loud with human noise, but does it also sound different in a medium chemically altered by excess carbon dioxide, microplastics, and the further impacts of these changes in the plant, animal, and microbial community? A sperm whale’s clicking song at 180 decibels can be part of a lively communication with other whales near or far, a way to “see” bait in dark ocean depths, or scan human free divers. Considering that whales probably discern and enjoy acoustic qualities of their songs and vocalizations, which songs do they experience as most enjoyable or beautiful?

On the other hand, what kind of ambience did the spermaceti candles produce for the humans that used and made them? Were the whale-oil-fueled lighthouses visible to whales migrating along the coast? What did London smell like when its streetlights were filled with whale oil, processed from tissues so visibly imprinted with stress chemicals?

By asking such speculative questions, artistic approaches let us publicly stage the mechanisms that distinguish which specific dimensions, out of the breadth and complexity of environments, are deemed recordable, classifiable, or worthy of inquiry. What is understood as relevant and what is not included in or removed from the discourse because it is considered unimportant? Or in other words, which questions are cast as silly or fantastical—and why?

Artistic practices serve to frame the much-cited phenomenological gap between Anthropocene processes such as human-induced species extinction or global warming, and what we are able to experience in our everyday lives. To go a step further, artistic practices often aim to “operate beyond the divide between the sensuous and the intelligible,” on the interdependent relationship between what can be experienced and what can be thought. Whatever London might have smelled like with its whale-oil lamps, people would not relate the smell to the stress or extinction of whales because these simply were not concepts that eighteenth-century Londoners had. Given today’s relatively new awareness of human impacts on the environment, the same smell might be perceived and received very differently. The task of this project is thus to re-consider the division into the sensible and intelligible, reflecting on different ways that our sensory experience is already ordered by culturally determined assumptions that precede it, and simultaneously to re-sensitize and re-order the breadth of material interrelations. This begins with rendering visible those relations that do not stand in a directly-recognizable connection with anthropogenic value systems, but could instead lead us to recognize the vulnerability, uprooting, or destruction that the histories of whale inscribe.

In the iterative workshop series “Future of Carbon” conducted by Clemens Winkler, local natural resources containing carbon were found and burned. The participants then took part in powdering, smearing, imprinting, or liquefying ashes into electric circuitry and discussed its potential technological uses. Here, burning became a practice and a process of subtraction and relating anew to carbon, which is bound in solid, viscous, and gaseous states. In “Dust Blooms,” a long-term artistic research project of Alex Toland and various collaborators, diesel soot filtered by roadside vegetation is made visible using microscopy and experimental soot-printing techniques. Zooming into the microscopic scale of highways and traffic circles, the marks of combustion-driven mobility are etched onto the surface tissues of unassuming species that contribute to the filtration of atmospheric pollution for the benefit of human health. Andrés Burbano works with digital media on topologies of global CO2 data in comparison with local data, thinking of a place (Bogotá in this case) as a planetary sensor. Winkler’s, Toland’s and Burbano’s experiments work to reflect on carbon in a way that allows us to better see and understand the histories of carbon’s framing and configuring by the technosciences and industry, bringing, in turn, another dimension to the experience of these materialities. From the vantage point of the twenty-first century, we understand that while the dimensions of carbon made visible by technoscience enabled the humans to see more, to do things in the dark, humans were at the same time blinded, deflected from other senses and sensibilities for their surroundings. This contrast lies at the heart of the Anthropocene debate when it comes to aesthetics.

An artist’s process can also be seen as a kind of ambient poetics, as Timothy Morton noted, or “making the imperceptible perceptible while retaining the form of imperceptibility.”14 Morton describes how the “Save the Whale” campaign used recordings of whale songs to draw attention to underwater environments inaccessible to humans, appealing to our aesthetic senses to relate to marine environments and their inhabitants without requiring us to understand the nature or meaning of those songs. The human ear listened, and the response—of new conservation strategies and marine protection policies—followed.

An artistic approach does not necessarily extend our senses to allow us to look deeper or farther into something, as optical or acoustic instruments might do. Rather, it enables one to multisensorially experience things in relation. The color and smell of whale oil lamps’ light or soot can be perceived differently today than they were in eighteenth-century London, because sensing comprises not only what is individually re-conducted every time we sense something, but also mechanisms of distinction that are socially constructed over time. Londoners today and two hundred years ago have different modes of comparison, and different pre-constituted potential objects of perception. Artistic experiments can, for example, present soot that is identical—yet not identical—to the soot in the air of eighteenth-century London, allowing us to both engage with materiality of those conditions, and simultaneously confront the fact that their full reconstruction remains impossible, always missing eighteenth-century social-cultural bits that the act of perception activates. Similarly, there’s a gap in perceptive capabilities between us and any other species, yet building experiments and experiences that aim to make tactile some of the impacts of Anthropocene such as the increasing acidification and pollution of the seas bring us closer to and underscore our kinship with creatures that share some of those sensorial abilities with us.

Illumination

With the primacy of vision and of economic productivity, it is perhaps little wonder that the Anthropocene is ever more brightly lit.15 Artificial light is one of the ways through which humans decouple themselves from nature, shunning the constraints of the Earth’s rotation that plunges them in darkness every twelve hours, and enabling round-the-clock markets and infrastructures for continuous work and consumption. The journalist, librarian, and indigenous rights activist Charles Lummis described in 1894 the Pueblo Isleta tale of why the moon only has one eye.16 Once upon a time, the sun and moon both lit the Earth with their bright eyes so that plants and trees could constantly grow, and humans and animals could have more time to work and play. They noticed that their children became weary and so the moon sacrificed one of her eyes and allowed the other to slowly open and close, marking the phases of the lunar cycle and reminding humans of the gift of darkness, earthly rhythms, and sleep needed by all creatures. Today, the moon’s eyes have been opened again. In 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, Jonathan Crary describes a 1990s proposal by a joint Russian/European space consortium to install reflectors in orbit which would illuminate the dark side of the planet. This proposal perhaps best exemplifies where the propensity for perpetual illumination might lead, how the drive for productivity and continuous circulation ends in “an instrumentalized and unending condition of visibility.”17 As human vision is increasingly more privileged both as a human sense and as an instrument of world-making projections, as it produces more complex visibilities and ever further-reaching captures of nature, as it traces and foregrounds carbon flows as generative and reparative, other senses, and other connections and material relations become more and more obscured.

With new forms of visibility come new forms of exposure and vulnerability. Artificial light alone is recognized by biologists as an anthropogenic pollutant, harmful to wildlife and humans (including potentially having contributed to the causes of COVID-19 pandemic by disrupting the physiology and behavior of bats18—the nocturnal animals from which the virus “spilled” to other species). Despite these harms and dangers, the use of artificial light is unregulated, and its expansion or contraction is an incidental factor related to managing the costs and efficiency of energy use. Light and energy remain correlated, driving each other’s development as they have since the first human use of fire. And beyond disrupting dark environments, petroleum-based illumination plays a far larger role in the degradation of habitats and environments as a catalyst and enabler of extractive and polluting modes of industrial and technological development, including contributing to computational technologies and media-disclosed visibilities that shape human understanding of material relationships within environments.

When twentieth century systems ecology rendered natural environments as flows of matter of energy, and organisms as thoroughly embedded in networks of relations, it spotlighted those relations which were productive to the ecosystem. Carbon was rendered as a kind of energy currency which underpinned and unified material and social systems. Today when we speak of “carbon,” referring to both the gaseous emissions in the air and the carbon sequestered as a climate remediation measure, we are guided by these legacies of understanding carbon as that which is conserved when carbon molecules circulate through earthly spheres, taking on different embodiments and forms. This way of thinking is structured by extractive political economies that proclaim a sameness or commensurability underneath myriad carbon forms and processes. The idea of carbon as energy currency enables a new kind of commodification of nature through carbon markets and an “accumulation through dispossession,” where almost anything, even the vulnerable bodies of cetacean beings, could be calculated as a carbon sink or a carbon source to be exchanged. The carbon market itself becomes a system of control-through-calculation that casts the materiality of the biogeochemical world as pliant to human desires.19

Towards and aesthetics of relationality for the Anthropocene

Carbon has been used to render sameness as economic fungibility by reducing entities to one molecular dimension. But this shared chemical backbone could also be used to render connections across difference, connections that link forms of life and non-life in what Angeliki Balayannis and Emma Garnett have described as “chemical kinship.”20 Entities emerge as materially bound to chemical relations. At the same time, they are formed by the molecular and relational diversity and complexity of chemical and ecological processes, based on the spectrum of bonds that the carbon atom makes with other elements and itself, each arrangement enabling a fantastic diversity of forms of life and nonlife and their emergent relationships. This is perhaps nowhere as poignant as the carbon reservoirs that are formed when a dying whale falls to the ocean floor. Reflecting on the complex relationships between the living and nonliving, if such categories can even exist in the Anthropocene, Julieta Aranda and Eben Kirksey ponder the “double death” recognizable in whale falls as “life becoming nonlife on a planetary scale.” 21

The initial rendering of the natural and social environments as networks of relations as an ecosystem was followed by a proliferation of ecological re-framings: ecologies of media, perception, power, or information, to name a few. The Anthropocene has come to be marked by what we might call “aesthetics of relationality.” While relationality is the lens favored across the ideological spectrum, its roots in the discipline of ecosystems ecology carry into contemporary posthuman thinking the paradigms of technological and algorithmic forms of control, as Erich Hörl notes. Far from being just a metaphor, ecology as an analytical paradigm in any sphere “reflects the thoroughgoing imbrication of natural and technological elements in the constitution of the contemporary environments we inhabit.”22 Judith Butler also warns that the ecological metaphor and lens do not guarantee that the kind of relations they make visible are not causing harm. She writes that “relationality is not by itself a good thing, a sign of connectedness, an ethical norm to be posited over and over again against destruction; rather, relationality is a vast and ambivalent field in which the question of ethical obligation has to be worked out in a light of a persistent and constitutive destructive potential.”23 What is “worked out” of relational fields, and through what means, is critical for the politics of nature and coexistence. The insights gained in an aesthetic register allow us to foreground not only the more diverse and unseen kinds of relations but also what happens across them: the vulnerability, responsibility, separations, fears, or collectivisms required and produced by these profound interdependencies.

Our relation to the environment is always mediated, based on concepts and representations, in the production of which technologies have just as much a part as socio-cultural processes. Artistic approaches that open this pre-text of our understanding by asking silly or fantastical questions can expand the context of meaning to include new sensual experiences, new ways of re-establishing a relation to that which surrounds us. This approach may introduce a shift away from clear definitions and representations towards the intensities, differences, and indeterminacy that are part of them. Living in a time in which our understanding of vegetal and animal life, planetary processes, and the role of human influence on a planetary scale are constantly being reshaped, the necessity of conceptual knowledge in aesthetic theory that goes beyond the boundaries of the sensually perceivable seems necessary. Facing the limits of human comprehension in these matters allows us to attribute new forms of agency and sentience to our environments and the creatures we share these environments with.

Perhaps the best use of the lens of aesthetics is to turn it on ourselves to investigate our responses to different registers of whale encounters. To our twenty-first century ears, the twentieth century descriptions of hooking and harpooning whales, full of gruesome details of how long whales took to die in pools of their own blood, sound sickening. Erin Hortle suggests that this sickening feeling might be lurking behind our new love for this species, among other re-awakened kinships with other creatures.24 “Is this love based on an awareness of the guilt of the collective human?” Hortle asks. Does it respond to the feeling of shame brought about by a visceral experience of “getting it”—in the words of Thom Van Dooren25—“getting,” that is, the enormity of human impact across time that brought these species to near extinction? While attempting to define or find the markers of the Anthropocene, aesthetic approaches might be necessary if this new designation of our geological era seeks to orient us to new, less-destructive approaches for coexisting on the planet.

In the natural-cultural history of the whale and its material labor for human well-being and economic productivity, we can see a mechanism that is deeply inscribed into the relationship of the human being to its environment in the Anthropocene: an obscuring of a vast field of material relationships in favor of the visualization and amplification of those beneficial to the needs of humans. The question posed by the Carbon Aesthetics group is what role aesthetics can play in order to make other senses of material interrelations traceable, and to point to other and new relationships—not just relationships that have a directly recognizable connection to anthropogenic value systems, but reach ones that reach far beyond them, showing that the human being is embedded in processes and infrastructures that cannot be understood, operationalized, or perceived in their totality.

This contribution emerges from the conversations and visual research of a group of artists and humanities scholars who explore carbon and its relations under an umbrella project of the Carbon Catalogue. Carbon Catalogue is an artistic research project led by Karolina Sobecka, which explores the contemporary preoccupation with carbon as a by-product of the anthropocenic fossil fuel combustion. The Catalogue documents new designations, technologies and imaginaries of carbon, while also putting them in play, re-ordering and re-storying what carbon is becoming.

Carbon Aesthetics, a working group of the Carbon Catalogue, is organized by Desiree Foerster and brings together artists who turn to the material and the elemental, as well as to the symbolisms and common representations of the interrelations between bio-chemical and technological processes inherent to the carbon cycle. Artists in the group are Andrés Burbano, Myriel Milicevic, Alex Toland, and Clemens Winkler. The group members foreground emphasis on relations that constitute objects, which allow the movement of materials, and thus form the infrastructure for our meaningful interactions with the world.

Please cite as: Sobecka, K, D Förster, M Milićević, A Toland and C Winkler (2022) Whale Falls, Carbon Sinks. Aesthetics and the Anthropocene. In: Rosol C and Rispoli G (eds) Anthropogenic Markers: Stratigraphy and Context, Anthropocene Curriculum. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. DOI: 10.58049/f890-ek02

CARBON: A COMPANION SUBSTANCE

The aim of The Carbon Catalogue is to develop an increased sensitivity to our intimate relation to the material world around us. The choice of carbon for this purpose is rightly justified by three distinctive features of this element: its ubiquity, its connectivity, and its scalability.

Ubiquity

Carbon is a ubiquitous and abundant substance in nature and in the daily news. There is too much carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere and we know that it is a major cause of global warming. Carbon has also become the star of the Anthropocene because there are organic molecules of carbon (microplastics in particular) everywhere. So it is a familiar substance. Unlike plutonium or uranium, it is part of our daily sensory experience. Carbon has been around since the prehistory of human societies, since the invention of fire; its name derives from the Latin root carbo, which means “burnt.” And today carbon remains a major societal actor. Coal played a critical role in the rise of industrial democracy and workers movements, while oil abundance in the twentieth century reorganized geopolitical life and the relations between the West and the Middle East.i

The ubiquity of carbon, due to the variety of its modes of existence and interference with our daily lives, makes it advantageous for developing Anthropocene-conscious citizens. However, the anthropocenic perspective may also be disadvantageous because it narrows our view of carbon by overemphasizing the connection between carbon and the phenomenon of combustion. Carbon is identified with CO2, a gas released by the combustion of organic matter. Indeed, this gas, which was known as “mephitic air” in premodern times, played a crucial role in the long history of our intercourses with carbon. So deeply rooted in our relation to carbon is the paradigm of combustion that respiration has been described as a form of combustion, and living organisms considered as heat-engines. But we experience carbon in many other ways throughout our lives.

Carbon makes myriad compounds in addition to CO2. We tend to forget that carbon is the basis of all forms of life on Earth. DNA, proteins, carbohydrates… living organisms are all made of carbon-based compounds. Thanks to its unrivaled capacity for assembling a variety of long and complex molecules, carbon proved to be the best candidate for the emergence of life on Earth. We are made of carbon, of organic molecules. Carbon is ubiquitous in trees, plants, soils, and rocks. We also use carbon in its elementary forms when we draw or write with graphite pencils, when we use charcoal for purification devices, and whenever we admire diamonds in jewelry.

By focusing on the greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, we tend to forget that carbon has various cycles: in addition to the familiar biological cycle, carbon has a cosmic cycle in the universe; on our planet it goes through rocks and minerals in a long-duration geological cycle, and it traverses a medium-duration cycle controlled by temperature. Carbon is more than a chemical element. Carbon is more than life’s master builder. It is also a builder of civilization in two respects. First, if we understand that human civilization began with the mastery of fire, then through its implication in combustion carbon is a common pillar of human civilizations. Second, thanks to the balance between the carbon sink of the ocean and the carbon released in the atmosphere the Holocene enjoyed a relatively stable climate that made possible permanent settlements, reliable agriculture for food production, and the emergence of complex social organizations.

The anthropocenic treatment of carbon thus leads to an ironic situation. Carbon is viewed as the culprit, responsible for global warming. Standing in as the icon of all the greenhouse gases, it is the bad guy who must be sequestered. The energy transition is framed in the language of “carbon neutrality” or “zero carbon.” Literally, this phrase is nonsense, since carbon is the backbone of all life on Earth. A zero-carbon planet would be a lifeless and dead planet like Mars. In other words, the anthropocenic perspective on carbon is strikingly anthropocentric. Today even trees, forests, and soils are treated as carbon tanks and reconceptualized as “ecosystem services” for the purpose of mitigating climate change.

Connectivity

In addition to its ubiquity, carbon displays a remarkable capacity to make connections. As the Carbon Catalogue concludes: “it is the most connecting element.” This sentence can be understood in two senses.

In a literal sense, connectivity means that carbon atoms are characterized by their capacity to form chemical bonds with almost all other elements. As Sam Kean put it in didactic anthropomorphic terms, carbon is extremely friendly: it has low standards for forming bonds because its atoms need four additional electrons on its first shell to make eight and comply with the octet rule.ii They even make bonds with themselves, a capacity exemplified in organic molecules. The C-C bond is the basis of a wide variety of macromolecules, including the synthetic polymers that make up plastics.

In a metaphorical sense, carbon connects the various realms of nature. As the backbone of all life, it connects all living beings, especially plants and animals. It also connects us to soil and rocks. In this respect, we can have an experience of carbon in the broad sense of the term developed by John Dewey, referring to the interaction between human beings and the world.iii I mean that carbon aesthetics is not limited to our sensory experience of the world through respiration and nutrition. It refers to how we make sense of the world around us.

Scalability

In the twentieth century, carbon atoms were repeatedly selected among many others to build the conventional standards that science and industry required for dominating and exploiting the material world. They played a key role in the attempts to order the qualitative diversity of material elements and make them commensurable in quantitative terms. For instance, as it is impossible to weigh atoms, the system of atomic weights had to be set up on the basis of relative values. For this purpose, the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP) and the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) agreed to base the system of atomic mass on that of the isotope 12 of carbon. Carbon also provided the standard for the definition of a mole in reference to N, Avogadro’s number.iv Carbon thus connects the order of magnitude of elementary entities (atoms, molecules, ions, electrons, and particles) with the macroscale of populations of molecules engaged in chemical reactions. As a standard, carbon connects the nanoworld of atoms and molecules with the macroworld of human operations on matter. It makes them commensurable on a quantitative scale ordered by powers of ten.

More recently, CO2 has been elected as the reference gas for measuring the global warming potential of all greenhouse gases. This general equivalent enables experts to compare heterogeneous human activities in terms of their “carbon footprint.” The “carbon dioxide equivalent” (CO2eq) is the basis of a series of carbon markets, integrated into a giant scheme of carbon trading. By creating commensurability between heterogeneous things and activities, carbon dioxide is enrolled into a process of monetizing the world. Like gold and silver did a long time ago, CO2 has become money, an aerial money supposedly helping to regulate climate change through compensations and “offsetting.” Scale-making is key to developing a universal scientific and capitalist relation to the material world.v As a universal standard, carbon has extended the realm of scalability to oceans, soils, plants, forests, and whales, reconfigured as abstract, quantifiable, and exchangeable “ecosystem services.”

Towards a carbon aesthetics

In this context, the challenge of developing an alternative aesthetic experience of carbon becomes clear. In my view, a carbon aesthetics must open up a new way of being-in-the-world, of acting as a material entity among others and being affected by them. It would lay the foundation for a non-anthropocentric experience of the world, in which carbon becomes a companion substance, interacting with us while we depend on its cycles.

To increase our sensitivity to the material world does not necessarily imply turning to a subjective or poetic experience of it. We can also seek the help of non-human sensors, illustrated by the Bogotá planetary sensor. Sensing devices may increase our experience of carbon. It is not too difficult to have small, cheap sensing devices operating in cities, and collecting data about air, water, and climate. As Jennifer Gabrys argues, not only do sensors record information about the environment, they generate new relations with the entities they are recording. In doing so, they help us move beyond the subject/object divide, the bifurcation of nature and society by not just sensing, but giving a voice to carbon, bacteria, and animals.vi

I would like to suggest an additional way of breaking with our anthropocentric view of carbon and with it, the Anthropocene. Anthropologists have taught us to look at things as social and cultural actors.vii Beyond just the social life of things, we have to become aware of the lives of the stuff they are made of. Each of our commodities implies a variety of materials with lifecycles of their own. Carbon is one of them, and an important one because of the variety of its modes of existence: carbon can be considered a true persona with multiple lives. More exactly, there are multiple Carbon personae co-created by the natural dispositions of carbon atoms and the variety of human activities engaging carbon. Moreover, atoms and molecules are not isolated entities, they interact and they react collectively to their environment.

Finally, since carbon has been linked to writing (graphein) in its graphite form, Primo Levi, the chemist and writer suggests in the final pages of his famous novel that carbon was the writer of The Periodic Table. To build up a non-anthropocentric carbon catalogue maybe carbon could be the writer, the narrator of its multiple lives and histories. Just as the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa had various heteronyms “sign” his works of fiction, carbon could sign a variety of life stories interweaving human history, natural history, and cosmic processes. This collection of small narratives would compete with the grand narrative of the Anthropocene.

Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent is a French philosopher and historian of science and technology. She focuses particularly on the histories of chemistry and materials science.

- i Timothy Mitchell, Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil. New York: Verso, 2011.

ii Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon and other true tales of madness, love, and the history of the world from the periodic table of elements. New York: Back Bay Books, 2010, pp. 34–35.

iii John Dewey, Experience and Nature. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1929. https://archive.org/embed/experienceandnat029343mbp

iv A mole corresponds to the amount of substance of a system which contains as many elementary entities as there are atoms in 0.012 kg of carbon-12 (6,022045.1023). Thus N atoms of carbon-12 have a mass of 12 grams.

v For more on scalability, see Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Frictions, An Ethnography of Global Connections. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

vi Jennifer Gabrys, Program Earth. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

vii Arjun Appadurai, ed., The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.