Critical Environments

Since Jakob Johann von Uexküll introduced the concept of “Umwelten” (“environments”) into biology, it has become widely accepted that any living being must be considered as part of a specific spatio-temporal-sensual frame set by its own perception and interaction with its surroundings. In contrast to this biosemiotic conception, George Evelyn Hutchinson proposed the term ecological niches to account for the hyperspace in which living beings are able to dwell, leading much later to the theory of niche construction, which had a great impact on the evolutionary understanding of how species adapt the environment for their specific purposes. As different as the epistemic approaches of these theories may be, a common denominator is the fact that the survival of any particular species depends on its ability to transform itself as well as its habitat through various physiological, biochemical, and indeed “technological” processes.

No single species has done more to this end than Homo sapiens. Having shaped our surroundings ever since we started to use fire and stone tool technologies, our potential to actively transform our surroundings has changed dramatically over the course of the Holocene, beginning with the rise of agricultural practices such as animal husbandry, crop breeding, and landscape modification to improve productivity. However, since industrialization in the nineteenth century and especially during the Great Acceleration in the middle of the twentieth century, humanity has transgressed its spatio-temporal, biological, and energetic boundaries. Humans have fundamentally reorganized the environment to a point at which the traces of human existence have been permanently inscribed into the Earth, and altered what can be understood as the planetary environment, or planetary niche, as a whole.

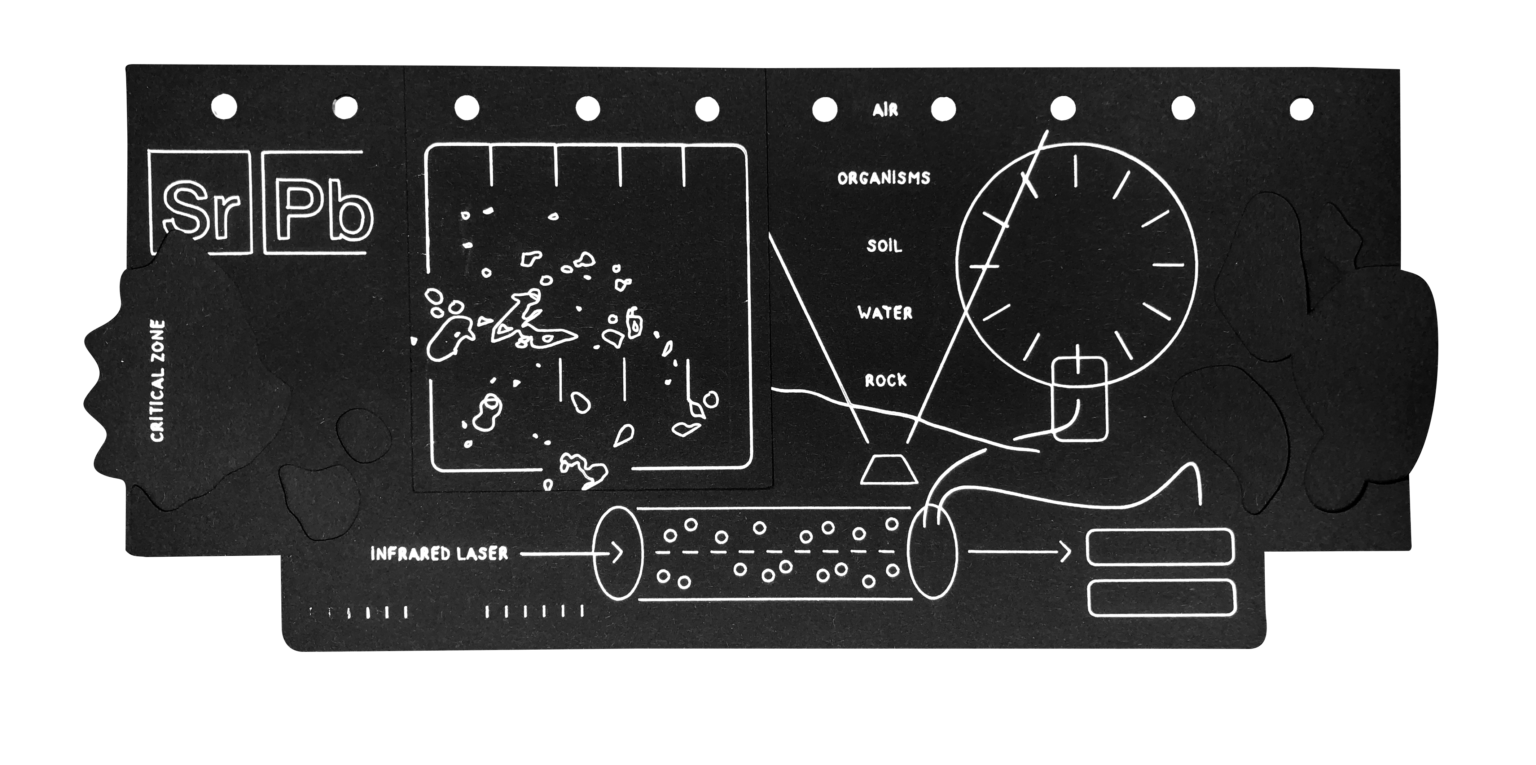

In this dossier, however, the focus is not on the alteration of biogeochemical cycles, but on the residues and impacts of pollutants in their different media of transmission and exposure, such as airs, waters, and soils. The spotlight falls on the recordings within and by certain environments: sensitive environments, like estuaries and lagoons, become natural archives of exposure and general human intervention; toxic sites of human creation, such as tailing reservoirs in mining areas, turn into stratified memorials of contamination and social inequality.

Socio-technical systems like the industrial chemistry complex produce not only novel materials in the form of waste, which accumulate to form new strata, but also a substantial number of toxic by-products which are now distributed in various metabolic cycles and pathways. Similarly, heavy metals like lead and organic pollutants such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) contaminate groundwater, soil, and marine environments, affecting microbes as well as whole ecosystems, thus presenting an incalculable risk to the living conditions of millions of plants and animals—including human communities. Although the danger of harmful substance exposure and a general understanding of the risks associated with industrial processes have been on the agenda of many institutional actors for a long time now, numerous ecological disasters have continued to alter environments irreversibly and cumulatively, at local and global scales.

Even as the social and political consequences of these tendencies are in certain ways highly visible around the globe, their full extent cannot be assessed yet. If a living being is considered to react and adapt to sensory data of its particular “Umwelt,” what new concept of environment is gaining traction now—in a time when novel materials and the use of technology at an industrial scale registers traces in nearly all of Earth’s spheres? Now that humans have constructed a technosphere niche unable to cope with the disasters of its own making what new bearing does the term “critical environment” hold?