The Case of Air

Anthropogenic markers signal disruptions, and the disruptions to the atmosphere are one of the most emblematic in this regard. Literary scholar Eva Horn unpacks air as an environing medium that has always entangled human life and the environment in very specific ways. She argues that the manifestations of a disrupted atmosphere—in the form of air pollution, contagion, and as artificial climates and climatic changes—reveal an entire history of multiple models of characterizing human-made transformations.

Aerial view of high-rise buildings covered with smoke in Shanghai, China. Photo by Photoholgic via Unsplash

What was once simply called “the air” today must be translated into several distinct terms referring to different phenomena and pertaining to several scientific disciplines: “the atmosphere,” “climate,” “air quality,” and “a mixture of gases.” The Wikipedia entry for “air” begins: “The atmosphere of Earth, commonly known as air, is the layer of gases retained by Earth’s gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere.”1 As a specific mixture of gases (78.8% nitrogen, 20.9% oxygen, 0.93% argon, 0.04% carbon dioxide, other trace gases, and 0.4 to 1% water vapor), air is the object of study of atmospheric chemistry. As the planet’s atmosphere, air is a system of flows, pressure, and temperature that distributes energy and matter over the entire globe. Its varying states are called “climate,” which today is defined as “the ‘average weather,’ or more rigorously, as the statistical description in terms of the mean and variability of relevant quantities over a period ranging from months to thousands or millions of years.”2 Climate is the average weather in a given locality, but it also connects these local states, constituting one unified planetary system as one element of the whole Earth system. As such, the air is the research object of atmospheric physics, otherwise known as climatology. What connects these different disciplinary approaches is a shared understanding of the air as an environment, or, more specifically, as an “environing medium” of human and nonhuman life.3 Thinking about the air as an environing medium means tracing the practices and cultural techniques that create certain types of knowledge, generate data, and devise models of the air as environment. How do the given science-based definitions conceive of the nature and behavior of this environing medium? And how do they think of the relation between humans and their surroundings in respect of a medium that is at once invasive and pervasive, intimate and global? What are the benefits and what are the limitations of this perspective?

This essay tries to cast current science-based conceptualizations of the air against the backdrop of entirely different, historically and culturally marginalized, or “outdated,” forms of knowledge about the air. If the Anthropocene, with its intricate conflation of the human and the natural world, no longer allows for a strict separation nature and culture, then how can we conceive of an environment such as “the air” in ways that account for this conflation? How can we think about humans as not being separated from or external to this environing medium, but rather stuck in the thick of it? I would like to suggest that it might require a little bit of cultural “anamnesis,” or “unforgetting,”4 in order to (re)discover forms of knowledge and perception, as well as theoretical frameworks better suited to conceiving of the entanglement of humans with their nonhuman life world.

But let us begin with the question of “anthropogenic markers.” What are anthropogenic markers with respect to the air? When it comes to natural entities such as the atmosphere, the biosphere, the oceans, and even specific landscapes and biotopes, anthropogenic markers are disruptions. Disruptions and disturbances in a system, however, lead to a better understanding of its functioning.5 So thinking about disruptions of the air as the “environing medium” of human life might help us understand the human relation to this environing medium more succinctly. I would like to suggest four phenomena in which humans leave their traces in, or disrupt, the atmosphere: pollution, contagion, climate change, and artificial climates. While this list is not comprehensive, these four disruptions are emblematic of the human-caused transformations of the air in the Anthropocene.

One of the overarching tasks facing a multidisciplinary approach to the Anthropocene is exploring what different perspectives from various academic disciplines can bring to the table. What are the insights afforded by the perspectives of the natural sciences on the one hand, the social sciences/humanities on the other—and, conversely, what are their blind spots? To draw a picture as to how these perspectives diverge, but also complement each other, when it comes to “the air,” let me briefly sketch a natural scientist’s approach to the disruptions I have mentioned—albeit from the limited perspective of a humanities scholar.

In the case of pollution, a natural scientist would ask: What are the specific substances that we consider to be “pollutants” of the air? How do they behave in the air? How can we measure and quantify the degrees of pollution and their effects on living beings? From such a perspective, pollution is treated as an environmental problem rather than one of public health or social order—that is, a problem external to the questions of human perception and responsibility. As regarding climate change, the main challenges for the natural sciences lie in understanding and modeling the extremely complex behavior of the climate system. To do this, a planetary perspective of the atmosphere is vital. While many of the major mechanisms of the climate system seem to be well understood, the consequences of changing variables and their interconnection—most specifically their interconnected tipping points—remain difficult to fully grasp.6 Consequently, a data-driven, global perspective on climate as a single unified system is the basis of our current scientific understanding of climate change. This, however, makes it hard to relate to the phenomenon of a changing climate from the perspective of national mitigation policies, local scenarios of transformation, and even individual consumerist choices and political commitments. In comparison to these first two major anthropogenic disruptions of the air, “pollution” and “climate change,” the two latter phenomena, “contagion” and “artificial climates” may seem marginal. However, regarding contagion, we recently learned (or rather, remembered) that the air can be a stealthy and efficient medium for the transmission of pathogens (such as COVID-19, smallpox, measles, tuberculosis), triggering novel research on air flows in confined spaces and the transmission of infection through airborne viruses. Lastly, artificial climates, such as heated and air-conditioned architecture, insulated spaces (such as greenhouses, shopping malls, and the Biosphere 2 project in Arizona), and cooled local microclimates (through shading, ventilation, or moisturizing) may seem to be nothing but an afterthought of climate change. While locally attenuating the effects of climate change, air-conditioning, as we know, contributes significantly to the problem. In the face of rising temperatures and extreme climatic conditions, however, the age-old dream of controlling the air may no longer be confined to just greenhouses and air-conditioned shopping malls. What we are witnessing now are research projects and thought experiments to take this dream to a planetary scale, as technological designs expand to global climate engineering and even the terraforming of other planets.

What the natural sciences do, broadly speaking, is measure, analyze, and model these anthropogenic disruptions as “matters of fact,” that is, as natural phenomena or technological conundrums. While scientists gather and process data and seek technological solutions, a humanities approach to air, by contrast, deals with stories, images (both real and imaginary), systems of knowledge, frameworks of interpretation, and questions of accountability and responsibility, but also with bodily sensations and affects.7 The humanities address “matters of fact” as “matters of concern,” as sociologist of science Bruno Latour famously put it,8 or elements of nature in relation to human beings: How are humans affected by the air, physically, psychologically, and socially? How can humans account for their interventions into the air? The particularity of the humanities is that they do not look for universal laws or global markers but rather for historically, culturally, and locally singular frameworks and representations. This approach involves a historically or culturally differentiated perspective: How did different periods and cultures think about the air and its man-made disruptions? What modes of perception and which systems of knowledge are/were used to make sense of the different states and alterations of the air? Could the past become a “usable past”, as Julia Adeney Thomas puts it, by offering us models of thought that can “re-connect social systems, ecological systems, and ultimately the Earth System”?9 To further outline this perspective, I would like to indicate what a historical approach may have to offer regarding the four disruptions of the air that we are currently considering.10 In each case, the relation between humans and the air as an environing medium is fashioned in a way that is from the perspective of the natural sciences, highlighting different aspects of the relation and transforming or translating air into a matter of concern for humans as social beings.

Pollution

Wood chip burners in smog, taken as part of a smog survey by the US Environmental Protection Agency in the 1970s. Photograph by Tomas Sennett, Environmental Protection Agency, Wikimedia, public domain

Air pollution, first perceived in the early modern period, has been, from the onset, thought of as a political and social problem. A treatise published in seventeenth century England complains about soot from certain industries (such as breweries) and private households poisoning the London air and affecting both human bodies and “the passions of the soul.” It calls for the king to intervene in favor of public health by planting fragrant trees in the city center.11 As the term “smog” (“smoke” + “fog”) indicates, air pollution is understood as an unfortunate conjunction of weather and fumes, thus often treated as a form of particularly “bad weather.”12 With the onset of industrialization, pollution came to be seen as the inevitable price of modernization, symbolizing progress, but also social disorder (e.g., the fog becoming so thick as to favor street crime). From nineteenth-century London smog to the Clean Air Acts in Europe and the US in the 1960s and 1970s, the fight against pollution historically has been approached primarily in terms of public health, social inequality and disorder, and the regulation of industry—and not in terms of environmental deterioration. Even if it is understood as a conjunction of natural and industrial causes, within the concept of pollution, air is politicized and thus “humanized”: a product of human making. Air quality is seen as a battleground for human health, social order, and political regulation. What has changed over the course of air pollution history is its perceptibility: while denizens of nineteenth-century metropolises complained about the murkiness of the air, the problem today with microparticle pollution is that the latter is often imperceptible, reaching noxious levels long before the degree of pollution can be seen, felt, or smelled.

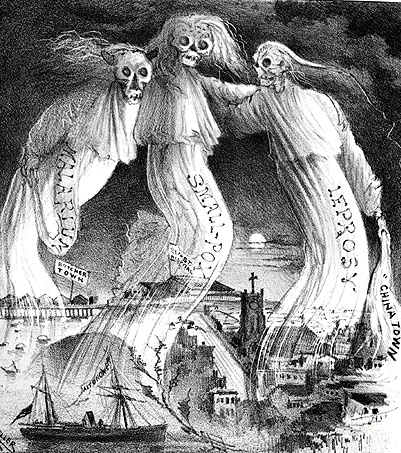

Contagion

If it were not for the current pandemic, contagion through airborne pathogens would surely seem to us today a relatively rare, negligible, and somewhat outdated idea of a disruption of the air. Yet until the end of the nineteenth century, the “miasma theory” was the predominant framework for the scientific understanding of the origin and transmission of epidemic diseases. Within the paradigm of miasma, noxious exhalations emanating from the soil, swamps, sewers, graveyards, livestock, hospitals and other sites of defecation, putrefaction, and decomposition were identified as the cause of many kinds of illnesses. Miasmas are the exhalations of life and death. Historically, if several people in the same location had the same type of symptoms, the illness was attributed to the common air they breathed. The concept of miasma is thus a shorthand for the relation of living beings to the place they inhabit together; it relates to both their social and their natural milieus. Air was treated as a medium connecting human beings, animals, landscapes, architecture, and natural processes. It was seen as a social medium, where “social” not only referred to the community of humans but also connected humans to the nonhuman, that is, landscapes and animals, as well as to the processes of life and death. Social existence meant being in the same air, breathing and producing a shared air. Air was thus seen as a pervasive, often dangerous, environment, with humans highly susceptible to its influences. But air could be sanitized through preventive measures of “hygienic medicine”: draining swamps, banishing sources of decomposition from the city, street cleaning, sewerage systems, airing houses, and avoiding bad smells and steamy climates.13 While human life was seen as endangered by the environment, humans were also responsible for “managing” this common environment. As in the case of pollution, the miasmatic dangers carried by the air were thought to be easily, even overwhelmingly, perceptible. Miasma theory involved an extreme sensitivity to smells14 and keen attention to the temperature, pellucidity, and moisture of the air. Here, the air is an object of apprehension and “care”—an environing medium, intricately entangling human life with its surroundings.

Climate change

The notion of “climate change” as an alteration of the atmosphere on a planetary scale wouldn’t have made sense to anybody living before the latter decades of the nineteenth century. For more than 2,000 years, the concept of “climate” described local conditions or environments: “airs, waters, and places,” as Hippocrates put it.15 To fully understand the disruption of the air brought about by climate change, it is necessary to delve into the conceptual history of climate. What was climate before it was defined in a modern sense as “the average weather”? Initially, “climate” was not a meteorological but a geographical term, designating the latitude and environmental conditions of a specific location: the landscape with its seasonal patterns, temperatures, winds, and soil and water quality, along with the bodily constitution of its inhabitants. As a geographical category, “climate” became a shorthand for the relation of a given culture to its geographical environment. Thus, human cultures and their differences were explained by the different “climates” (i.e., regions, natural environments) they were situated in. The diversity of human life reflected the diversity of landscapes and habitats. With “climate” as a concept binding specific human life forms to the conditions in which a given population found itself in nature, “climate theory,” then, was used for cultural comparison, e.g. in political theory, in historical accounts, or as part of ethnographic descriptions.16 Often historical developments were accordingly explained in relation to changes in the (local) climate. This does not necessarily mean that a given culture or society was determined by the environment, but, as the philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder put it, “inclined” or nudged by its environments toward certain social institutions, forms of livelihood, mentalities, and cultural techniques.17 “Climate”—or rather, climates—was a shorthand for the singularity of civilizations. It was used to explain the ways in which they were both shaped by and actively transformed their local environments. In this understanding of climate, “climate change” would not necessarily be seen as a disruption or pathology of the air.18 It would account for the historical changes in a culture, and even for “cultural heydays” as particularly good “vintages.”19 A changing climate (whether human-made or accidental) could be observed, narrated, and made sense of within the framework of human history. Against the backdrop of this premodern concept of climate, climate change as we understand it today, as a global phenomenon, is a radical abstraction. We see climate as a global system, not a local predicament linked to human civilizations. We like to see cultures as radically independent of their natural environments. Our sensitivity to climate, the seasons, weather, or the states of the atmosphere has all but disappeared, at least in Western societies. “There is no bad weather; there is only the wrong clothing” is the motto of this “forgetfulness of the air,” its radical externalization.20 This is why, apart from local weather disasters, climate change seems to be so hard to translate into political measures. Its local and temporal scales far exceed the spatial scope (mostly national) and the temporal horizons of politics (4 to 5 years) as well as the expectations, experiences, and hopes of individuals and collectives.

Artificial climates

Today, artificial climates are everywhere. The aerial environments that surround us are, to a great extent, air-conditioned spaces, heated rooms, greenhouses, urban heat islands, parks, gardens, or plantations. All are technically-created insular or insulated microclimates. Indoors, these microclimates are adapted to a norm of temperate air suited for human men (ideally 22°C, 50% moisture), which is slightly too cool for women. If pollution, miasma, and “bad” climates indicate a disruption of the environment that infringes on human well-being, then artificial climates seem to offer the solution to the problem of polluted, sickening, unhealthy air.

For a long time, artificial climates were seen as a utopian promise that would liberate humanity from the vicissitudes of natural environments, and particularly the dangers of the air.21 As such, they were designed subject to the whims of urban architects (as in the Crystal Palace in London in 1851), colonial powers (building huge greenhouses to showcase “their” tropical flora during the Victorian era), the developers of large-scale scientific experiments (such as the Biosphere 2 project in Arizona in the late 1980s), and, simply, science-fiction writers. An artificial climate is produced by air moderated according to an ideal of human physical comfort, making it a form of “humanized” environment. It is also the utopia of an entirely controllable environment in terms of its composition and physical state. As an ideal of human control over nature, technologies of modulating the atmosphere on a planetary scale are currently being promoted as a countermeasure to anthropogenic climate change. If climate change is understood as a dysfunction of the planetary atmosphere, then climate engineering offers the promise of a quick “fix.”22 However, as the cultural theorist Peter Sloterdijk has argued, climate engineering does on a large scale what artificial, insulated climate modulation does on a small scale: it performs an “explication,” that is, it makes explicit latent forms and mechanisms of a given system or medium—the medium air. For Sloterdijk, “explication” is a technical reconstruction of the complex workings of the air, under the precondition of disrupting it.23 The explication of the air transforms it into a planetary technology: an Earth system of human making.

Thinking about the air in the humanities

Pollution, contagion, climate change, and artificial climates can be seen as anthropogenic disruptions of the air as a complex, pervasive, and vital environment. They provide for an understanding of air not just as atmosphere but as a medium of life: of physical life, of the community of human and nonhuman life forms, and ultimately of societies and civilizations.24 Each of these concepts, however, thematizes the air in a different way: through the lens of pollution, which was once seen as a mixture of meteorological forces and human-made fumes, the disruption of air is now treated essentially in relation to human health—with humans seen as both responsible for and victims of the altered composition of the air. Being an air of human making, pollution is a matter of policy and policing. Within the concept of contagion, exemplified by the old paradigm of miasma theory (and currently returning with a vengeance through the global proliferation of an airborne virus), air is understood as a dangerous environment in need of cautious management. Miasma is the signature of human life being entangled in a web of both life and death, of metabolism and morbidity. Miasma theory presents air as a medium of the social, binding humans to other humans as well as to nonhuman agents and diseases. However, with the paradigm shift, at the end of the nineteenth century, from miasma theory to germ theory as the framework for our current understanding of epidemics, air has become just one possible carrier of contagion. As a result, air is no longer treated as the single powerful agent of health and disease but merely one vector among several others. Air and its dangers have been rendered negligible and imperceptible: “the being of non-being, the matter of the immaterial,”25 a mere background to human social life. In the case of climate change, the idea of climate as a local predicament both influencing and influenced by human culture has been replaced by an abstract model of global averages, hypercomplex dynamics, and the unpredictable transformation of the Earth system. Climate today is understood in spatial and temporal scales that massively exceed human experience and perception: a global entity, not a local predicament. Climate has become temporal process described in terms of Earth history, not human lives. Lastly, artificial climates were once understood as protecting humans and other organisms from the vicissitudes of local climates. With modern-day scenarios of climate engineering and the potential terraforming of other planets, the possibility of creating and controlling the atmosphere is now being spelled out a planetary scale. Science fiction threatens to materialize as a future of very real planetary experimentation. Here, imagination feeds the dreams and nightmares that a conjunction of technology and the Earth system may have in store for us.

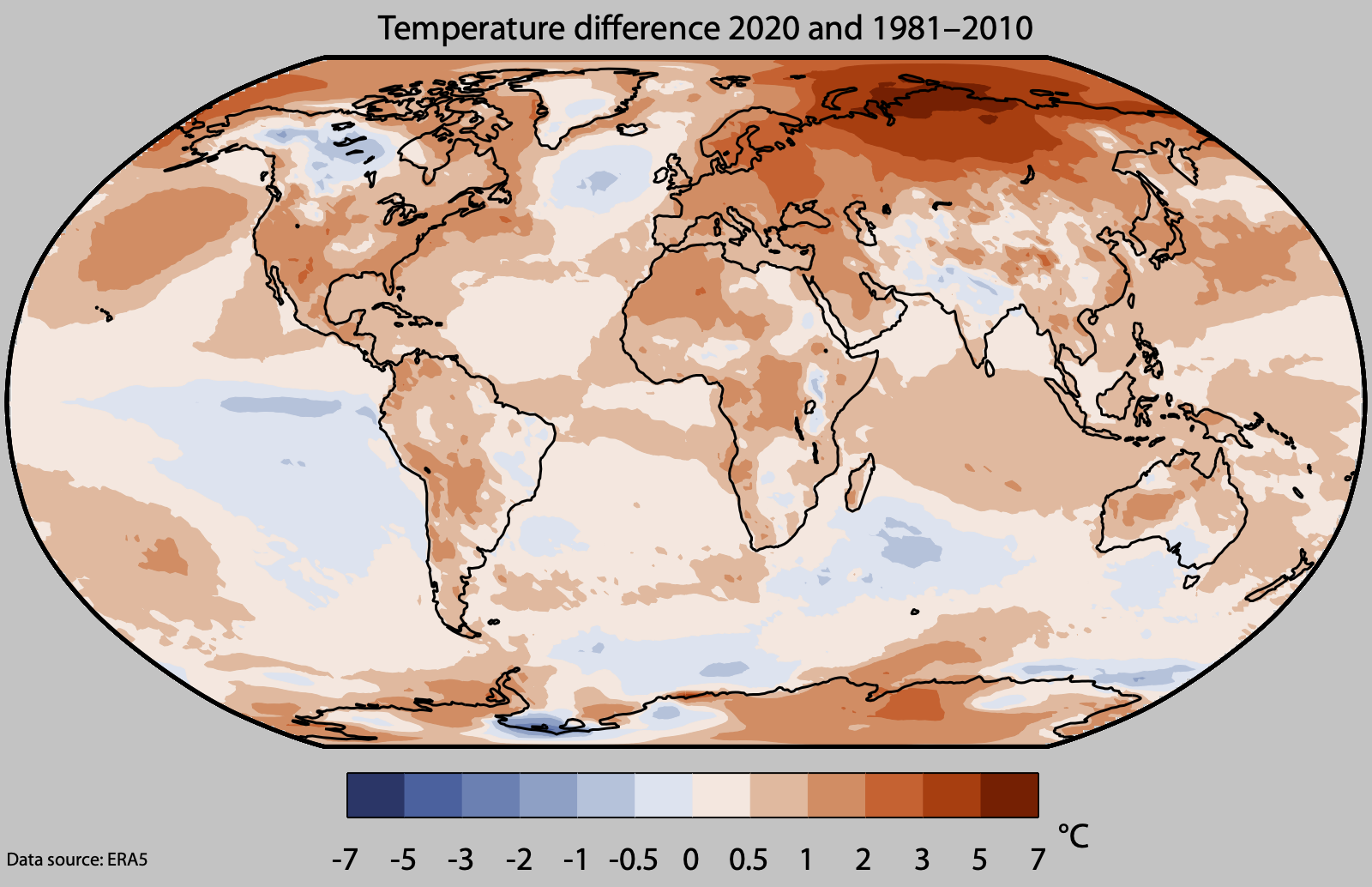

Air temperature at a height of two meters for 2020, shown relative to its 1981–2010 average. Source: ERA5. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service/ECMWF

Looking at former conceptualizations, we thus get a sharper understanding of the specificity and limitations of the current, science-based understanding of the air and its effects on human (and non-human) bodies and societies. It turns air into a planetary entity, exceeding the scales of human understanding and perception. Today, bad smells are just unpleasant. Bad weather needs just the right clothing—or disaster preparedness. Climates do not shape or influence societies, anything else would be “climate determinism.” Climate change is a matter of abstract averages—and needs a planetary techno-fix. Pollution is nothing but a problem of regulation. If all else fails, those of us in the privileged position to do so will retreat to the regulated air of shopping malls, offices, airports, homes, hotels, and gardens. Thanks to these artificial climates, the air is externalized and controlled, turned into a surrounding matter that we are rarely aware of as such. The abstraction of the air is the price for the immense and vital body of knowledge that modern science has gathered on the atmosphere.

In contrast, thinking about the air and its disruptions from the perspective of the humanities means thinking through alternatives or counterparts to this current scientific paradigm. “Outdated” historical models of the air can offer glimpses as to how we might understand the air not as an external environment or backdrop but as a medium enabling, shaping, and threatening human ways of life. While we vitally need the description, understanding, and prediction of the Earth system’s behavior offered by the natural sciences, we also need the view—or, rather, many singular, even incommensurable, views—afforded, so to speak, from within to complement scientific knowledge. While we need the understanding of climate as a planetary system, we also need the very specific framings of local communities and ways of life. While we may be used to understanding the life and health of the human body separated from its environment, we only begin to discover that the life of this body is profoundly and existentially entangled with this environment through symbioses with its microbiome.

We need to see air as a problem that needs our caution, care, and management on a local, even individual, level. While precise scientific data on the mechanisms and causes of pollution and contagion are necessary, we also need interpretive frameworks to relate these data to individual stories, personal and collective moods, and local forms of political decision-making to enable us to negotiate the attribution and distribution of responsibility for the various disruptions of the air. Of course, we need the “big picture” of Big Science, but we also need the singular stories, imaginations, metaphors, systems of knowledge, and sensitivities that have always related humans to air as their environing medium. Only in the singularity of these representations can we understand what being in the air really means and how we can assume responsibility for the air that we share.

Eva Horn is a professor of modern German literature and cultural theory at the University of Vienna. Her areas of research include disaster fiction, media theory, and most recently the Anthropocene. She is currently working on a book manuscript on “Being in the air. A cultural theory of climate.”

Please cite as: Horn, E (2022) The Case of Air. In: Rosol C and Rispoli G (eds) Anthropogenic Markers: Stratigraphy and Context, Anthropocene Curriculum. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. DOI: 10.58049/0pck-9×07