The Critical Environment of the Venice Lagoon

A Fuzzy Anthropocene Boundary

Venice’s critical environment is a paradigmatic case for comprehending socio-environmental history in dialogue with the Earth sciences. Venice, the water city, and its lagoon offer a multi-layered and very telling case for studying the longue durée of human interventions in local settings, a scale on which natural causes and human agency are usually not so easily separated. The diachronic and cross-disciplinary investigation that Venice invites is what the historian and philosopher Pietro Daniel Omodeo and the applied geologist Sebastiano Trevisani advocate in order to understand the forces that have led the globe to transition into the Anthropocene.

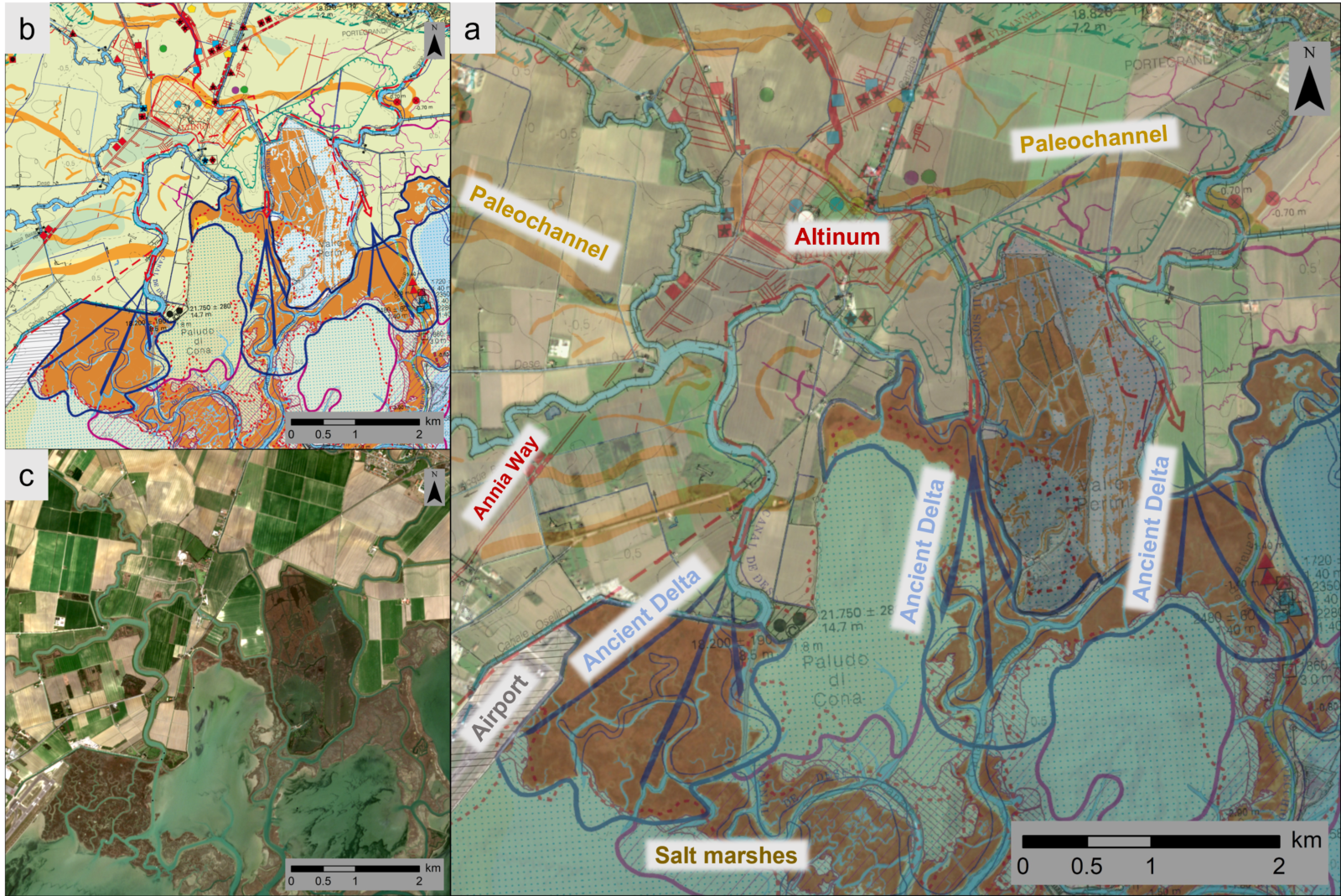

Venice’s archeosphere. An overview of the lagoon of Venice with the area of the Roman city of Altinum highlighted in red. Satellite imagery from ESA-Copernicus Sentinel 2 sensor, Copernicus Sentinel data, March 2021,

The Anthropocene Working Group’s current search for possible anthropogenic markers of the Anthropocene registers a decisive point in the process of scientifically assessing the possibility of introducing a new geological epoch. The markers’ identification will permit the geological community to establish the “lower boundary” of the Anthropocene in accordance with their specific methodological requirements, as well as allow for the choice and dating of a wide range of GSSPs (Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Points). These sought-after geological records should constitute, as it were, the “evidence” for the Anthropocene hypothesis; they must include globally ubiquitous and lasting measurable signals of human interaction with our planet, especially at an atomic and molecular level.1 As such, markers do not coincide with more localized or less enduring anthropogenic signals, which constitute a kind of low amplitude signal (not simply a background noise) against which a global break of major stratigraphic significance possibly occurred in the mid-twentieth century.

Beyond stratigraphy: Some preliminary and cross-disciplinary remarks

The semiotic distinctions between markers, signals, documents, and even symptoms connect and distinguish the various approaches to the Anthropocene hypothesis.2 Indeed, various approaches have emerged from the scientific community, the broader academic community, and the more public debate in a productive but sometimes confusing manner.

In the humanities and social sciences, the Anthropocene hypothesis has already produced an “environmental turn” which infringes against a well-established disciplinary and axiological separation between the realm of natural necessity and that of spiritual freedom. The sought-after Anthropocene evidence calls for scientific explanations that can include sociology and history in the explanatory matrix of the geological record. In other words, the anthropization of the Earth before and after the stratigraphic turning point of the mid-twentieth century, the moment of the so-called “Great Acceleration,”3 ought to take into account the structures of human societies, especially the emergence of capitalism as an economic, political, and cultural formation. This includes the function of technology for the material and intellectual production and reproduction of societies, whose diachronic lines of development, including in relation to the history of two major forces of world-transformation: science and technology.4 In-between the semiosphere of the humanities and the geosphere of the earth sciences, an intense interaction between the spheres of human labor (sometimes referred to as the technosphere and the ergosphere) and of life processes (the biosphere) takes place.5 From the viewpoint of the life sciences, one could speak of these transformations as the ecological construction of an anthropic niche that has expanded to encompass the entire planet. From the viewpoint of environmental humanities, the globalizing process of cultural-natural dynamics, whose scale was previously limited to local settings, has to be dealt with in historical terms. And from the vantage point of environmental history, the present task is to make some order in the fuzziness of the Anthropocene boundary that, one could say, constitutes the background signal from which the spikes representing the markers will be isolated.

With the distinct semiotic considerations of these various approaches in mind, when moving from a formal stratigraphic viewpoint to a geoenvironmental and historical one, the boundary of the new epoch does not look sharp but rather fuzzy.6 In order to deal with it, the signal of human interference must be analyzed in its completeness, from the first low amplitude and geographically-fragmented intensities of some millennia ago (like the first fires or agriculture terraces) to the ubiquitous high-amplitude intensities of recent times (such as the impacts of industrial production or land use changes). But we also must consider the fuzziness of the Anthropocene boundary because, unlike the “usual” stratigraphic boundaries, we are looking at geological time from a very near perspective, and are ourselves an essential factor shaping the phenomenon we observe. To acknowledge the inherent fuzziness of the boundary is a natural process for disciplines such as history, archaeology, environmental geology, geomorphology, and ecology. For scholars working in these fields, the entire duration of the recorded signal of human interaction with the planet is of interest.

A detail of the Malamocco inlet, in the area of deployment of the 19 mobile barriers. Photo by Sebastiano Trevisani

The lagoon of Venice: Where natural and human forces have long mixed

For an inquiry into the entangled evolution of humanity and nature, the lagoon of Venice is emblematic. The natural conditions of the lagoon are the basis for the development of a specific form of water civilization, while specific historical processes account for numerous developments of the environment. The approach of the French school of the Annales has made historians aware of the importance of taking the material dimensions of history, including environmental factors, into account. A masterpiece such as Fernand Braudel’s La Méditerranée et le monde méditerranéen à l’époque de Philippe II (1949) has called attention to the centrality of geography and territory, their conformations (determining shape and structure), and the possibilities they open for cultural developments.7

Braudel regarded Venice as a jewel that was in many ways the result of converging global factors, especially the long-distance trade guaranteed by maritime hegemony, and which symbolizes, even at the aesthetic level, the wealth of Mediterranean civilizations. But while Venetians could not at large shape the Mediterranean basin, which already served their interests quite well, they transformed the coastlines, lagoon, and the hydrological basin. Present-day land and waterscapes around Venice are the result of centuries of engineering, policies, and a constant scientific effort to understand natural processes and master technology in order to determine the territory’s conformation. Such collective and political intentionality marks the specificity of a process in which natural forces and human agency fuse together.

Geomorphological map superimposed on the satellite imagery. Intense anthropogenic interferences on the geosphere are evidenced, the ancient ones (Altinum, Annia way, and the river diversions) as well more recent ones (Venice Airport). Note that ancient morphologies such as river paleo-channels and fluvial deltas (currently salt marshes) extensively characterize the Venetian area. Map courtesy of Geomorphological map of the Province of Venice, scale 1:50000, ed. A. Bondesan, M. Meneghel, R. Rosselli, A. Vitturi, Florence: Lac, 2004; Satellite imagery from Copernicus Sentinel data, March 2021

A critical environment whose hydro-morphological settings hold particular historical and symbolic relevance, Venice and its highly-anthropized lagoon have been transformed by elements and humans for millennia at a depth that does not admit a separation between natural causes (mainly rivers, the sea, and subsidence) and human agency.8 Thus, Venice Lagoon, with its delicate and dynamic geoenvironment, is an apt location for studying geosphere-anthroposphere interactions and discerning the potential complexity and informative richness of the “archeosphere” (see the above map and the early modern engraving below).

The socio-hydro-morphological structure of the Venice Lagoon: Rivers and human agency

The geomorphological landscape of Venice and its surroundings constitutes a living historical archive of interactions between humans and the geoenvironment. The richness of historical documentation from the Middle Ages to the present allows for a fine-tuned understanding of the economic stakes and the political decisions that were taken, especially in early modernity (beginning in the late fifteenth century), in order to preserve and reshape the environmental niche on a geological level (the preservation of the lagoon against sedimentary filling), a biological level (in connection with agricultural uses of water, its industrial exploitation, and fishing), and a cultural level (navigable infrastructures such as canals, city architecture and aesthetics). Early modernity marked a geo-anthropological transition, in which major river diversions determined the present state of affairs: the historical character of the Venetian environment also bears witness, then, to the path-dependency of geomorphological and cultural processes.

Early-modern Venetian water experts were well aware that the morphology of the lagoon depends on natural as well as cultural factors, as documented in the early days of activities of the long-lived Magistrate of the Waters. The origins of this institution can be traced back to the Renaissance and was terminated in 2014 in the wake of scandals linked to the movable dams MOSE project. Initially, it was a commission of officers (Savi alle acque, or “water savants”) who were in charge of all matters linked to water policy in the three main aquatic areas: the lagoon, the coast, and the rivers (Ventrice 2008).9 The Magistrate of the Waters benefitted from the advice of experts called proti, which included one mathematically-trained advisor, and directed public works that transformed the lagoon into its present shape.

During the long and well-articulated history of Venice urbanization,10 a succession of anthropic interventions deeply affected the geoenvironment of the lagoon and the surrounding areas, including the coast and the alluvial plain. In this context, the diversion of the main rivers flowing into the lagoon (see below), conducted by the Republican government of Venice centuries ago, had profound impacts on the geomorphological and ecological equilibrium.11

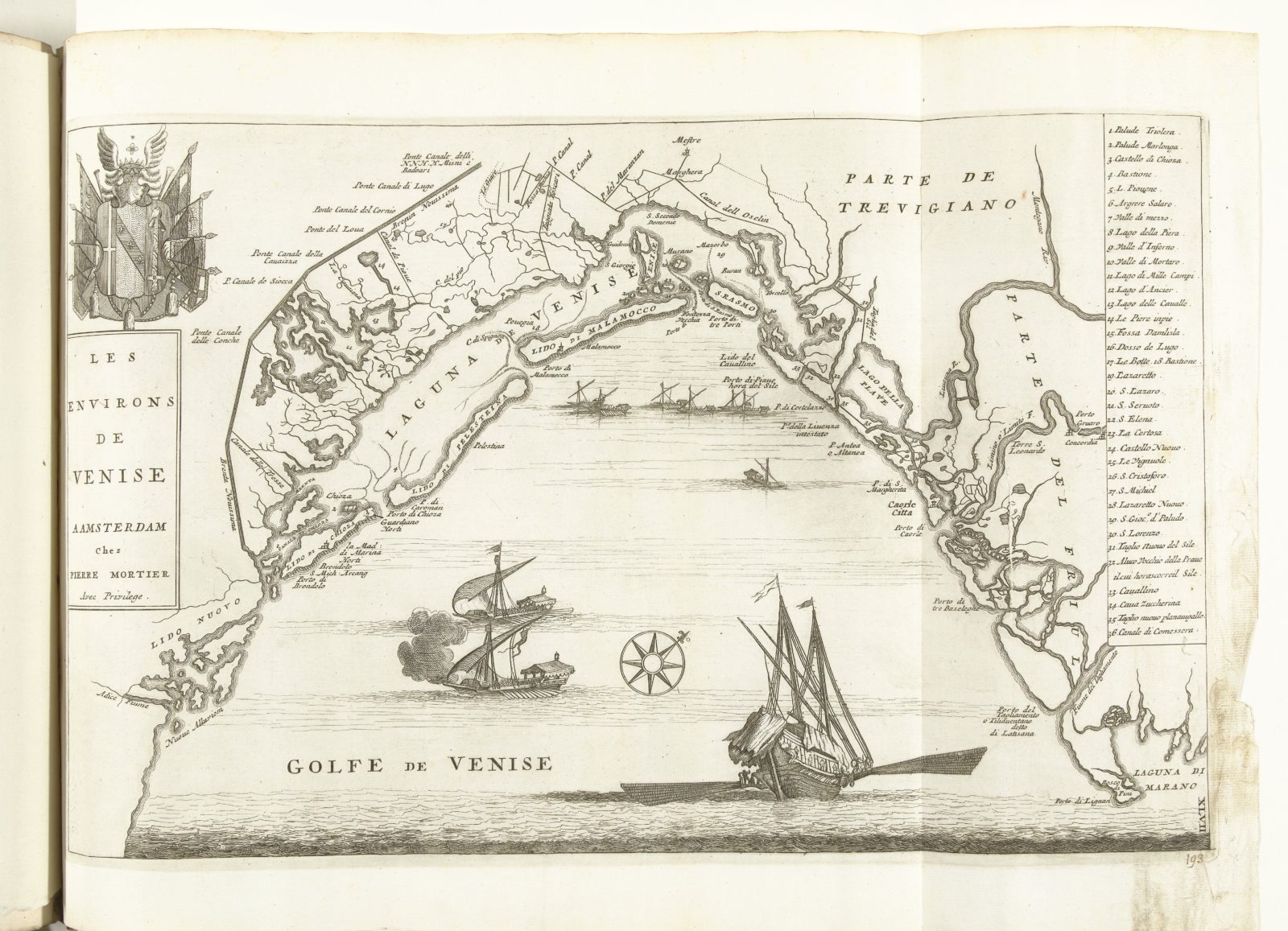

An early modern engraving (Amsterdam, ca. 1702) of Venice and its Lagoon, in which the river diversions are clearly visible. Public domain

In the lagoon we can still see the remains of ancient river deltas, once flowing into the lagoon and later diverted by the Serenissima government, which now have been reshaped by tidal currents and transformed into salt marshes.12 The diachronic expansion of the historical center of Venice—at the expense of tidal morphologies—is another example of the pervasiveness and complexity of human impacts on the geosphere. Today, the tidal and storm surge hazard facing Venice, locally referred to as acqua alta, is yet another example of the complexity of geosphere-anthroposphere interactions, which also includes the human alteration of the hydrodynamic equilibrium of the lagoon.13

A quick look at the geomorphological map of the area (above) is sufficient to perceive the dynamic complexity of the Venetian landscape.14 By highlighting underlying shallow natural morphologies and anthropic structures, this map captures the dynamic character of the lagoonal and fluvial geosystem. For example, the extensive presence of fluvial paleochannels inland and ancient fluvial deltas in the lagoon outlines the possible interactions of the fluvial system with the tidal dynamics and lagoon morphology. Another example of such geo-anthropic dynamics are the Roman settlements and roads whose presence highlights the prolonged and ancient anthropization of and complex relationships with the geoenvironment.15 A last example is offered by the morphologies of buried lagoonal channels in areas that were subjected to land reclamation, which form another aspect of human interference in the delicate lagoonal geosystem.

Water politics: Water as a socio-economic resource

Considering all these transformations of Venice’s critical environment and their motivations, one could say that the relationship between Venice and its surrounding waters, the rivers, the lagoon, and the Mediterranean Sea has always been economic. We understand “economy” in a broad sense; the “economic” motivations behind the transformation of the territory relate to both society’s production (the production of goods, labor, and transportation) and reproduction (in connection with life and its most elementary needs). As an infrastructure for transportation, water was the environmental precondition for Venice’s maritime preeminence from the Middle Ages up to the early-modern shift in European global commerce away from the Mediterranean Sea towards the Atlantic Ocean. While the Arsenale, the state-run navy shipyard, reminds us of the centrality of maritime technologies for medieval and early-modern Venice (including the military dimension),16 the harbor and the shipyards still bear witness today to the economic importance of accessing the sea and the exchanges it makes possible.17 The so-called canale dei petroli, the deeply excavated “petrol-channel” connecting the industrial pole to the open sea, was excavated in the ‘60s to keep pace with a growing harbor and chemical industry.18 Severely altering the currents in the lagoon, the canale dei petroli has had far-reaching environmental consequences.

As for the relevance of water for “economic reproduction,” that is, for the maintenance of life at its most basic level, the scarcity of drinkable water on the island of Venice has been a problem throughout its history. Until the extensive exploitation of artesian aquifers became technically possible in the nineteenth century, Venice relied on a disseminated system of cisterns and wells, which were constructed all over the city in order to collect rainwater.19

At the juncture of social production and reproduction, agricultural uses of water and fishing constitute two often-neglected but significant aspects of the economic interests that guided the hydromorphologic transformation of the territory. A variety of water uses of the past can be rediscovered thanks to the archival documentation of fishing and farming. They were further linked to local manufacture and various forms of labor in the preindustrial age.20

Fishing occupied a prominent place among water-related labor activities. The Venetian authorities considered the stable supply of fish at a controlled price to be crucial in order to guarantee justice and social order. Their concern is reflected by legislation measures throughout the centuries, and the strict regulation of the fish market.21 Not only the prices, but also the reproduction of fish in the lagoon and the Adriatic Sea was considered to be of vital political importance. Attentive regulation of fishing techniques and the permitted times of year were implemented as a means to guarantee the city’s prosperity.

The engineering of the hydrological basin, especially in the fifteenth century when Venice took control of large inland territories, was aimed to preserve the lagoon’s navigability. Moreover, its water was considered to be the most effective defense of Venice—the lagoon gave the city “fluid walls.” For the sake of the lagoon’s preservation, it was necessary to examine and comprehend the natural phenomena and their connections. As early as in the fifteenth century, Venetian administrators recognized that deforestation had consequences on soil erosion in the mountainous mainland, which led to the accumulation of sediments in the lagoon.22 On the other hand, timber was important for housebuilding, shipbuilding, and maintenance of the Venetian fleet. For these reasons, the preservation of forests became as important as their exploitation. The use of timber resources became strictly regulated in order to safeguard their renewability. As has been argued, early-modern Venetian environmental politics constitute a historical example of how to manage resources in a non-destructive manner.23

The uses of water were similarly controlled, especially concerning canalization on the mainland.24 On the question of irrigation canals in the countryside, the interests of agriculture and navigation were in conflict with each other, because the regulation of waterflows had the protection of Venice’s insularity as its main goal at the expenses of other possible interests. This created a tension between the mercantile elites, who lived in the capital, and landowners, whose main interests were in the mainland.

Measures against polluting uses of water for manufacture in the city emerge from historical sources, especially in connection with textile production. These problems only foreshadow the gravest problems that have emerged in the twentieth century, in the form of chemical pollution from the industrial complexes of Marghera, located on the mainland shore of the lagoon. Beyond the biological sphere, these large-scale industrial developments have impacted the area’s geology, because the pumping of water from confined aquifers for industries and households has accelerated the subsidence rate of Venice. Public intellectuals denounced these effects as early as in the ‘60s after the acqua granda (high water) of November 4, 1966, which was a clear sign that industrially-caused subsidence enhanced the impact of seasonal high waters;25 the frequency of high waters is further augmented by global warming and sea level rise. As a consequence of the many vital economic interests which depend on it, the politics of water can be regarded as at the crux of Venetian history.

Alongside this sketch of economic interests and political decisions, a final note should be devoted to the role that knowledge, especially scientific knowledge, has always played in the transformation of territory like the Venetian waterscapes. The large body of scientific sources discussing water, water management, hydraulics, sea tides, and cartography that emerged out of the Venetian context bears witness to the great expansion of scientific knowledge that took place in this city, making it into a major early-modern center of book printing in connection with the flourishing University of Padua.26 Some of the most impressive scientific works, including technological inventions and engineering projects, were produced by water practitioners working for the Magistrate of the Waters, such as Cristoforo Sabbadino, hydraulic engineer of the Magistrate in the sixteenth century.

The Raffineria Porto Marghera, across the lagoon from Venice. Photograph courtesy Christoph Rosol

From anthropogenic transformation to Anthropocene globalization

Venice is best understood as a glocal reality. That is, the water city can be understood only from a multiscale perspective, including the global viewpoint, a fact made particularly evident by the threat that global water surge poses to the survival of the “water city.”27 By considering the environmental politics and resource management in a spatially limited “scarcity economy” of the past—the long-lived Republic of Venice—the Venice Lagoon offers an instance, if not a model, to rethink the entangled geological, environmental, economic, and political problems of today’s global society, which faces the same problem of resource renewability at a planetary scale.

From the example of Venice, we would particularly stress the importance of cross-disciplinary research aimed at comprehending the socio-historical reality of the critical environments of the Anthropocene. In general, the study of historical and archaeological records sheds light on how science, politics, and socio-economic interests interacted, from the perspective of geoenvironmental policies and adaption to constantly changing environmental conditions.28 To remain with the Venetian case, archival administrative, technical, and political documents are a largely unexplored mine of geological and environmental data. Critical environments, as exemplified by the case of Venice, concern at once the “first nature” and the “second nature” (to use a Baconian distinction between physical and cultural contexts), and this data are both natural and social.

Braudel once taught historians to look at the Mediterranean basin as the most important “archive of itself,” because political history is rooted in societal structures and, ultimately, geology. As he saw longue-durée material culture (including economy) as strictly dependent on geography, the layers of nature and material culture—human geography, social history and political history—unfold according to different rhythms and temporalities. For Braudel’s historical perspective, geology constituted an almost-immutable precondition of human relations and deeds. And yet the Anthropocene predicament calls for a revision of this neat picture. It urges scholars in different areas to consider the dialectics between culture and nature, as the latter is constantly and deeply transformed by the former. Therefore, no unidirectional dependency can be surmised anymore. The new geological epoch that is currently under evaluation implies revising history, not only at the level of history-writing, which is the specific task of environmental history. What is more, we have to deal with a new and widespread awareness that human history—as a material, world-transforming history—is “inscribed” in nature: in the environment, the landscape, the layers of the Earth, and its cycles.

The Anthropocene GSSP will hopefully provide us with the searched-for evidence, a ubiquitous and lasting “inscription” of human agency in the stratigraphic record. The historical-environmental connection of such markers with less profound, more localized, and less enduring geo-anthropological phenomena is the task of the environmental humanities. The connection of the two lines of inquiry can be seen as the achievement of a much-awaited cross-disciplinary paradigm for the Anthropocene. The critical natural-artificial environment of Venice constitutes a suitable terrain of cross-disciplinary exchange, as well as an apt location to observe low-signal interactions between humans and their natural setting, which we see as an important continuation and integration, in the humanities, of the current AWG’s work.

Pietro Daniel Omodeo is a cultural historian of science and a professor of historical epistemology at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Italy. His research focuses on science, philosophy, and literature in early modernity, as well as on historical epistemology.

Sebastiano Trevisani is Associate Professor in Applied Geology at the University Iuav of Venice. His main research activities are related to geocomputational approaches for the analysis of geoenvironmental systems, with a special focus on geosphere-anthroposphere interlinked dynamics—such as hydrogeology, natural hazards, geoengineering issues in urbanized contexts, geomorphometry, and sustainability.

Acknowledgments: ERC Consolidator Project EarlyModernCosmology (Horizon 2020, GA 725883); FARE Project EarlyGeoPraxis (Italian Ministry of University and Research, cod. R184WNSTWH); Max Planck Partner Group The Water City (Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Berlin-Ca’ Foscari University of Venice)

Please cite as: Omodeo, P D, S Trevisani (2022) The Critical Environment of the Venice Lagoon. In: Rosol C and Rispoli G (eds) Anthropogenic Markers: Stratigraphy and Context, Anthropocene Curriculum. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. DOI: 10.58049/GHP3-SR58