Reading the Anthropocene Ocean

How do tropes and images of a changing ocean—its creatures and depths, abundances and dangers—operate in a larger system of cultural sensemaking? Literary scholar Killian Quigley engages the “weave of image, mode, and genre” through which (sub)marine spaces and their futurities are written and read, tracing the disfiguration and deformation of an anthropocenic biosphere that swells beneath the sea’s surface.

As a program for the correct identification and coordination of meaningful signs, Anthropocene work is, among other things, a kind of literacy work. It is fundamentally concerned, as the literary scholars Tobias Menely and Jesse Oak Taylor have argued, with discerning and cultivating best practices in “reading and narrating.”1 It is engaged in anticipating such practices, too. Imagine, proposes the geologist Jan Zalasiewicz, a group of extraterrestrial “explorers” who visit Earth millions of years from now. What methodology might they best use to “read the signals” the Anthropocene inscribes? How, for starters, will the visitors discover and comprehend the many “drowned cities” that rising waters will have inundated and seabed sediments will have buried?2 To draw attention to questions like these is not necessarily to cast doubt on the prospect of their being satisfactorily answered. Rather, it is to underscore that writing about the Anthropocene is so often writing about reading, and writing about readers. If an image of alien searchers presents an unsettling prefiguration of humanity’s extinguishment, it also furnishes the weirdly consoling idea that certain among our habits of interpretation, like certain of our leavings, may persist well after we’re gone.

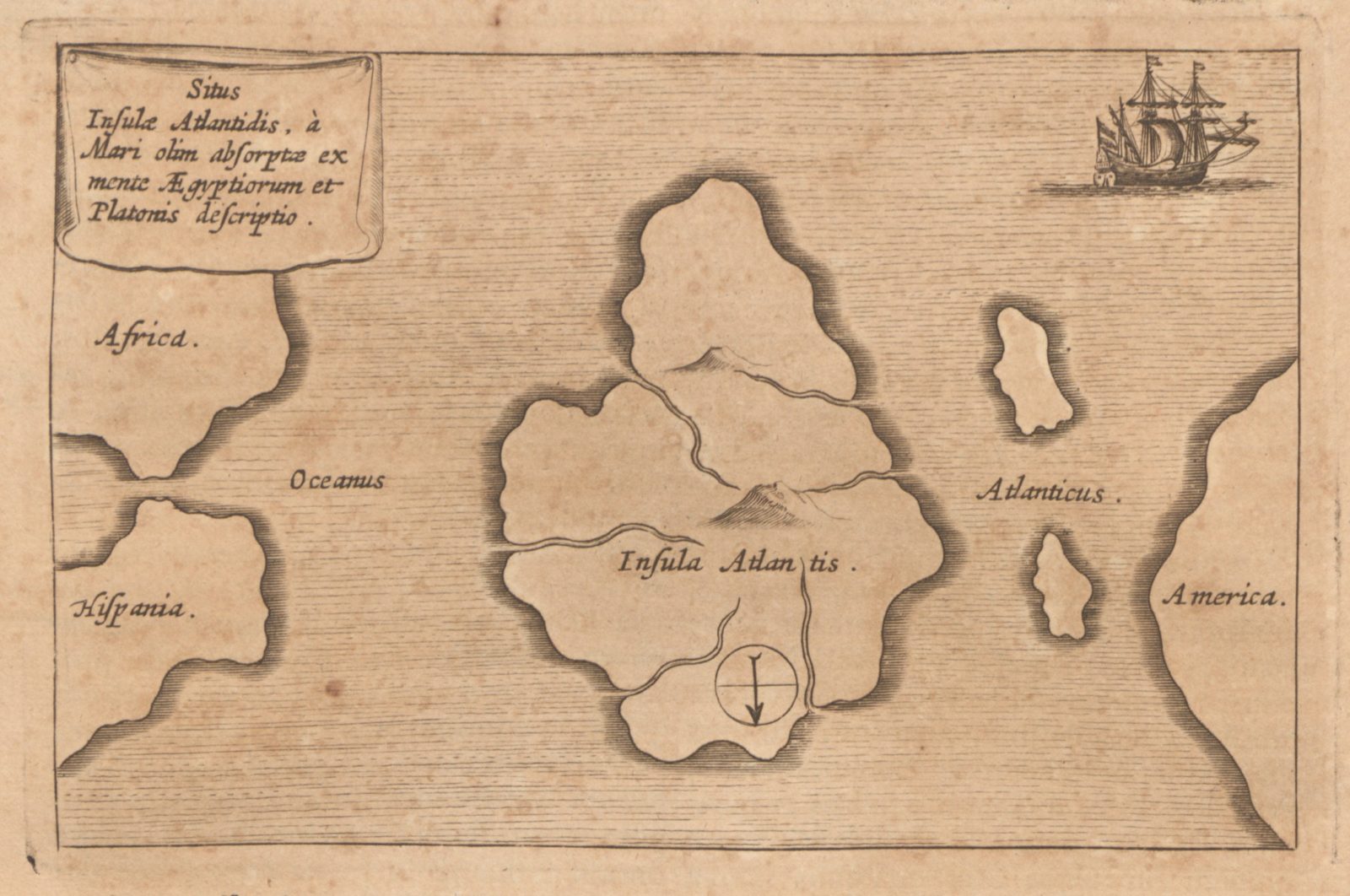

In 1664, the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher produced a speculative (and conveniently unverifiable) map “of” Atlantis. Athanasius Kircher, Mundus Subterraneus, 3rd edition: Atlantis, 1678. Courtesy Rare Book and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University, public domain

As the ancient myth of Atlantis attests, drowned cities are unusually potent icons of planetary pasts and futures. And as practically goes without saying, a substantial part of their expressive power derives from the specific interpretive problems posed (for some) by submersion. What becomes of the signatures of human habitation, and of human memory, when they are overtaken by a “non-signifying field”?3 Contemplating some photographs of properties located, precariously, along exceptionally vulnerable parts of the United States’ Atlantic seaboard, the nonfiction writer Elizabeth Rush has imagined the ocean rising up and up until the homes vanish “beneath the flat blue surface of the sea, where clouds would skate and bloom as though nothing and no one had ever existed below.”4 This is anthropogenic sea-level rise as a crisis for legibility, and saltwater as an unusual—if not singular—agent of erasure. We might also recognize the image as an invitation to reckon with ways of looking that struggle to perceive the ocean as more than so much “essentially featureless” space.5 The planet is presently becoming, in postcolonial literary scholar Elizabeth DeLoughrey’s words, “more oceanic.”6 If this is so, then the distinctive and diverse natures of sea-writing—or “thalassography”—as well as sea-reading must be key preoccupations of Anthropocene conjecture.7

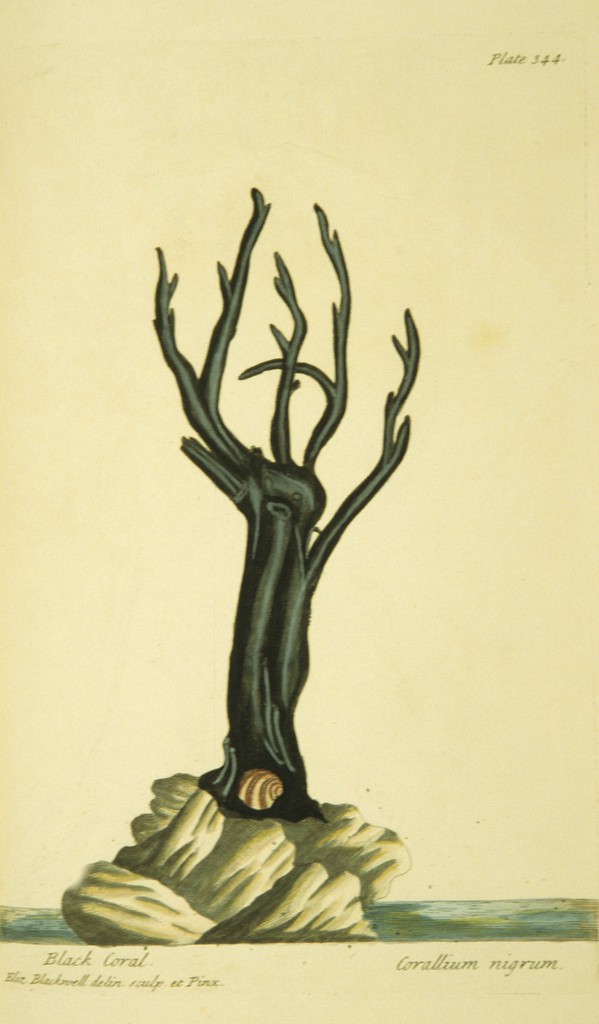

Anthropocenic and oceanic literacies are at stake, jointly and urgently, among predictions of biotic change in marine environments. Interpreting the fossil cores of scleractinian corals from the Great Barrier Reef and elsewhere, scientists have discerned remarkably fine-grained narratives of historical states of, and alterations in, marine life.8 With the help of these accounts, it may be possible to foreshadow future seas with unprecedented nuance. At just the same time, however, transformations at work upon Anthropocene seas appear to portend disastrously poor reading. Assuming a continuation of the status quo, write Zalasiewicz and paleobiologist Mark Williams, the “most likely end result is that the diverse, beautiful ecological systems still dominated by reef corals and fish will be replaced by ‘slime-rock’ systems dominated by algal and microbial mats and jellyfish.”9 Thus emerges a perverse twist in the dialectic of Anthropocene writing and reading, whereby storytelling’s increasing sophistication in the present generates visions of the extreme diminishment and deformation of oceanic feature—and so the radical impoverishment of oceanic readership—in distant (as well as not-so-very-distant) times to come.

What are the implications for Anthropocene thought of the idea that ocean life is gradually simplifying, homogenizing, and—not coincidentally—becoming ugly? What are the consequences for sea-writing and sea-reading of an Anthropocene imaginary that anticipates the advent of oceans that are, in marine biologist Daniel Pauly’s view, either biotically “empty” or, perhaps more terrifyingly, “full” of “organisms we do not like”?10 (Replete with inorganic undesirables, too, of course: the “cyborg ocean” is the literary scholar Patricia Yaeger’s term for twenty-first-century seas inescapably pervaded by anthropogenic plastics.)11 In the little space remaining, I’d like to make a few observations about these trajectories in Anthropocene oceanity. I also want to venture a couple of claims about how our colleagues who dedicate themselves to the search for anthropogenic markers might understand the particularly literary aspects of their own and others’ endeavors. If there exist domains of practice where we might better and more frequently work together, surely writing and reading are among them. The following paragraphs offer a few notes and notions toward cultivating collective, intersecting literacies.

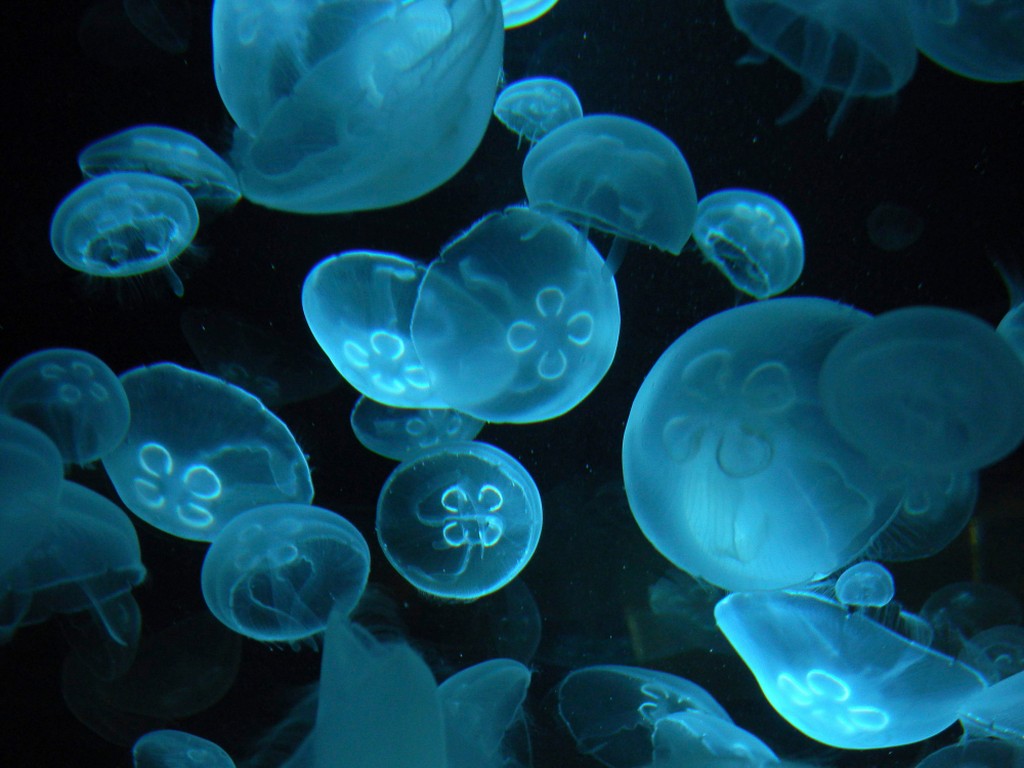

A narrative of decline and disappearance in gorgeous, heterogeneous marine ecosystems is an ecological forecast. It is also an invocation of one aesthetic of ocean worlds, a foretelling of the degradation of that aesthetic, and—in certain instances—a prophecy of that aesthetic’s replacement by another. “I now sincerely believe,” avers biologist Lisa-ann Gershwin, “that it is only a matter of time before the oceans as we know them and need them to be become very different places indeed.” As the planet loses “coral reefs teeming with life,” “mighty whales,” “wobbling penguins,” “lobsters,” “oysters,” and others, the “place” of those animals will be taken by “algae” and by incalculable numbers of “jellyfish.”12 Through the images she conjures as well as the sentences she writes, Gershwin aims to evoke a horrible regression from charisma to gracelessness, from the vividly characterized (“wobbling penguins”) to the unsettlingly incoherent (“soft, squishy organisms”).13 On these terms, biodiversity and descriptive detail retreat in tandem, as though species loss corresponds, more or less directly, with a diminution in the ocean’s capacity to be read and to be written. Narrowing prospects for articulation imbue anthropocenic ocean futures with a quality of awful inexpressiveness.

Moon jellies (Aurelia aurita) are among the cnidarian species whose populations have exploded in with the support of extractive infrastructures and nutrient runoff in the Caribbean Sea and elsewhere. Photo by Jennifer Stickney, Wellcome Collection

The foregoing is a sample of a larger archive of texts and figures that I think are worth contemplating together as parts of a loosely coherent vision, or “imaginary,” of marine futures.14 One obvious but important thing these accounts share is a commitment to conjuring marine futurity on a planetary scale, or on the scale of what is sometimes called “a world ocean.”15 Numerous scholars from varied disciplines have been examining the histories, politics, and capacities of a globalizing imaginary for comprehending histories and futures of transformational environmental change.16 I lack the space here to engage those conversations with anything like the nuance they deserve. For now, what I would like to stress is how reckoning the world ocean as a quasi-unitary figure makes it an object available to thought, description, narrative, and feeling—one that the literary historian Steve Mentz has recently described as the “biggest object in the world.”17 Working with the figure of a world ocean, it becomes possible to present the prospect of a multiply degraded object: disfigurements, according to these views, do not only subtract or desolate but also ruin, and the wrecks they produce appear irredeemably, and maybe uniquely, abject. The collapse of the world ocean’s biodiversity threatens to make the sea something more than barren: it portends the apparition of a repellent object.

The disfiguration of the future world ocean is foretold here through at least three closely related tropes: simplification, homogenization, and uglification. I am thinking of visions of food webs breaking down and reorganizing “into new, simpler, more species-poor combinations”;18 of a “radical simplification” of “marine systems” leading to a literally, texturally homogeneous “gelatinous future”; of looking to “the past” for “a glimpse of what our oceans may look like in the future”;19 and of reckoning the loss of marine variety in the course of an “ocean-wide slide into slime.”20 The philosopher Emily Brady has done some important work on the extensive and, in certain respects, co-constitutive relationship between certain “ecological values” on the one hand and certain “aesthetic qualities” on the other, particularly values and qualities like “variety, diversity and harmony.”21 Brady has observed, very recently, that in the context of global climate change, we are “moving into the territory” not only of ecological disaster but of “aesthetic disvalue.”22 The spectacles of marine degradation this essay has been considering offer striking examples of such relationships and of such movements: for the world ocean, they strongly suggest, ecological collapse and aesthetic catastrophe travel as one.

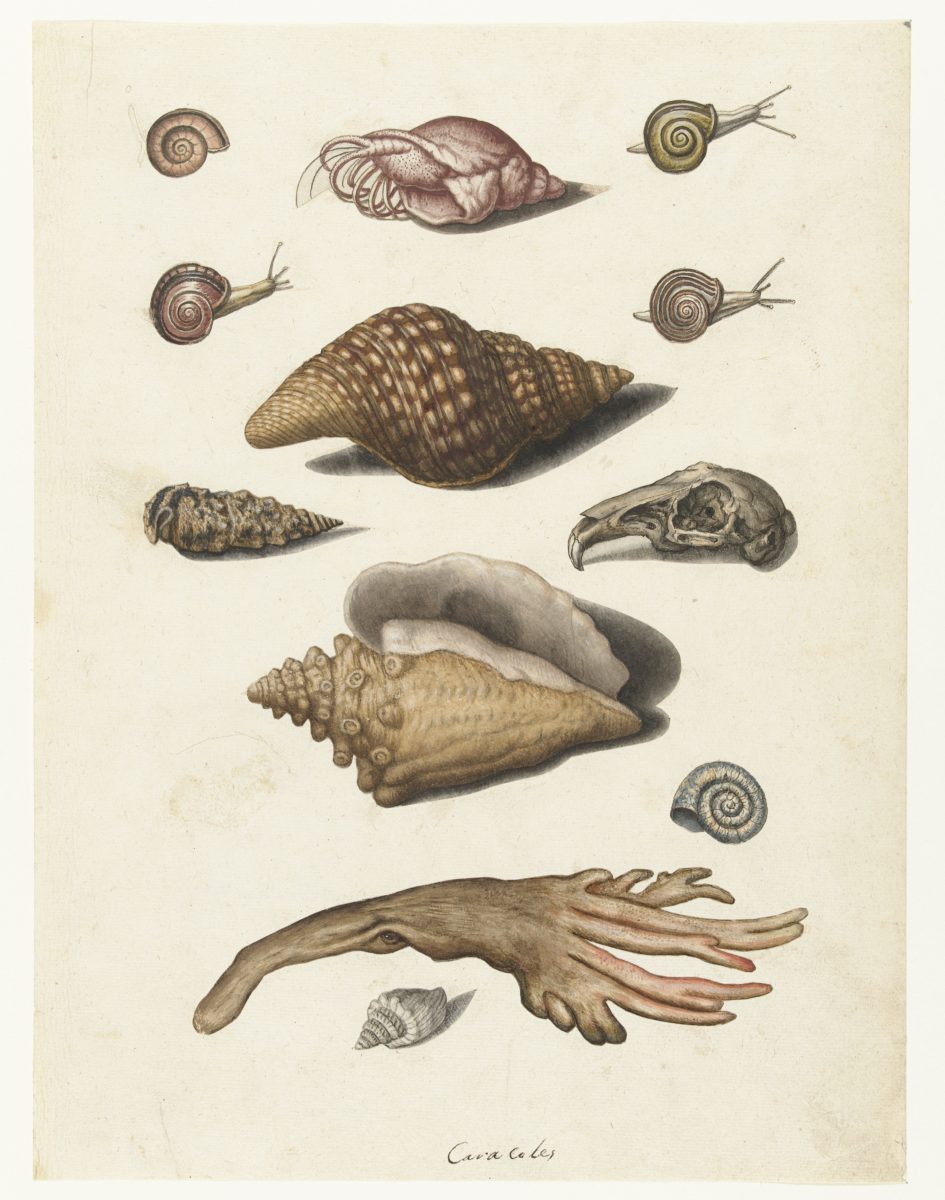

Anonymous, Schelpdieren, zeewier, slacken en konijnenschedel Caracoles, 1560–85. Courtesy Rijksmuseum, public domain

But perhaps we should go further. What more deeply haunts these thalassographic visions is a sense that, worse than a substitute or damaged aesthetic for the planet’s seas, the horizons of biotic change disclose a looming marine inaesthetic. This distinction, subtle but significant, separates that which disfigures from that which unforms; that is, it distinguishes that which mars the appearance of a thing, while leaving the thing basically intact, from that which altogether divests what it acts upon of its form. Predicting what lies ahead for seas left unprotected from our status-quo approach to fishing—“grab all we can, and eat it”—Pauly envisions an evolutionarily inverted future where “the more derived, larger animals” have been “replaced by simpler, smaller ones, all the way down to bacteria.”23 (“Derived,” here, refers to “the more recent stages or conditions in an evolutionary lineage,” or “the opposite of primitive.”24) Pauly’s scenario is startling because it coordinates the unforming of the marine biome with the unforming of time. In the environmental humanities theorist Stacy Alaimo’s words, this is a sense for anthropocenic oceans as “paradoxical, anachronistic zones of terribly compressed temporality where, it is feared, the future will move backwards.”25 Such a scenario is intimately connected, I am arguing, with an unresolved anxiety that the book of nature is being not so much defaced or revised as erased—that the Anthropocene’s exceptional “descriptive power” is tied up with its apparently devastating consequences for description.26

Widespread and growing recognition that Earth’s seas are being erased and unformed represents a stunning reversal from the common sense, current until late last century, that the marine biome is abundant to the point of being actually inextinguishable.27 This misconception’s histories are not only scientific, economic, and political, but also literary. In his Nereides; or, Sea-Eclogues, from 1712, the English poet William Diaper has one of his marine-dwelling characters chastise humans for forgetting the “Ocean’s watry Mass, / Whose boundless Depths the scanty Earth surpass, / Where thousand different kinds of living Forms / Lie hid in the Abyss, and brave the distant Storms.”28 Diaper was attempting to revamp and revitalize the pastoral, which by the early eighteenth century had become a pretty fusty poetic genre, by deploying it to render “the vast unseen Mansions of the Deep” in fanciful verse.29 What is worth remembering today about these fairly obscure old poems is the faith they express in the sea as an untapped resource for image and language—and for what we might call, not overdramatically, the entire poetic impulse. The inaesthetic ocean shuts this sort of justification down, neutralizing the sea as a subject for literature to the same extent that the mansions of the deep become stripped of living forms in their thousands (and more).

Ilse Bing, Seascape with Seagulls, 1936. Courtesy Lehigh University Art Galleries, public domain

What enters the voids—biotic, literary, and perhaps anthropogenically enlarged—that occupy the inaesthetic spaces of anthropocenic seas? Pauly’s imagery encompasses countless jellyfish, a “marine junkyard dominated by plankton,” and—most memorably—the “Myxocene,” or “age of slime.”30 By anticipating the overwhelming presence of unlikeable, and in some cases only obscurely identifiable, organisms, Pauly may seem to expose his forecast of oceanic emptiness as tainted by aesthetic and epistemological biases, and perhaps even by a kind of speciesism. (Does the junkyard lie in the eye of its beholder?) In any case, he is by no means alone in pondering the paradox that future seas may prove both barren and thronging. So-called dead zones, writes the ecologist Jeremy Jackson, are in fact the realms of an “extraordinary biomass of diverse microbes and jellyfish.”31 If this is more than an unfortunate inconsistency in need of summary correction, it is so because the category of the horrible, as philosopher of aesthetics Noël Carroll argues, is so deeply affiliated with the “interstitial,” the “contradictory,” and the “formless.”32 Like a decomposing corpse or a landfill laden with moldering waste, the undersea of the Anthropocene is suffused with abject, unformed stuff, as well as with the ghosts of those diverse, beautiful forms that structured it previously.

Pauly’s age of slime has acquired the intriguing and instructive distinction of being elevated, through its use by other writers, from a passing remark to an Anthropocene motif. “The Myxocene is not the future,” explains journalist and essayist Anna Krien in an overview of late twentieth- and twenty-first-century algal and jellyfish blooms: “it is already here.”33 As cultural history can teach us, the figure of mucilaginous oceans dates back a good deal further, to, for example, William Shakespeare’s Richard III (1593), where a dream of drowning yields a vision of “the slimy bottom of the deep.”34 Bearing this in mind, it may be appropriate to say that figures of anthropocenic oceans frequently hinge not only on predictions of evolutionary retrogression but also on the literal, unwilled reappearance of some rather antiquated (which is not to say irrelevant) senses for the deep. “Radically unaesthetic” (radicalement inesthétiques) is the way historian Alain Corbin’s influential book The Lure of the Sea (1988) characterizes early modern European regard for the ocean and the submarine.35 What made such regard frightful was not its being unshapely but its being unshaped, “unfinished,” “primordial.”36 I like “inesthétiques” for what I take to be its ambiguity, connoting not only that which is unpleasing or unsightly but also that which is outside, or maybe underneath, the realm of the aesthetic. It is in this respect that historian Anita Guerrini’s description of Corbin’s figure of the early modern sea as an “anti-creation” seems so apt.37 It was fearful and repulsive exactly insofar as it seemed an emblem of incoherence, an object lacking the sort and degree of integrity that might permit a prospect.

James M. Sommerville, Ocean Life, 1859. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, public domain

It is probably too neat to trace a circle from Corbin’s sources to the Myxocene and back again, but it is not frivolous to consider what it means for Anthropocene writings to have declared, wittingly or unwittingly, such striking imaginative kin. And I wonder what these declarations tell us about science, and about the story of progress that science has been understood to have made at sea over the past couple centuries. I think we might say that the consensus view of what marine science—particularly marine biology—does and has done takes the unaesthetic ocean as one of its narrative premises. Thus, for example, the historian Helen Rozwadowski’s argument, in Fathoming the Ocean: The Discovery and Exploration of the Deep Sea, that, until the mid-nineteenth century and the scientific and technological interventions heralded by that period, European consciousness generally “understood the deep sea as a great void that was empty and featureless, the antithesis of civilization.”38 Rozwadowski refers to a well-known trope of the ocean, and especially the undersea, as a kind of horror vacui—of what the cultural critic and architectural theorist Mark Cousins might have called a negative construction, productive of a particular species of ugliness.39 At times, scientific knowledge of the world ocean has appeared fundamentally concerned with—among many other things—counteracting such negativity by discovering subsea “forms”; this is precisely the way Margaret Deacon’s Scientists and the Sea characterizes the work of the marine biologists Charles Wyville Thomson and William Carpenter aboard the small steamship HMS Lightning off the north and west coasts of Scotland in 1868.40

Exploring the full extent of these resonances is well beyond the scope of this essay. But among their primary aspects is one that may hold special relevance for the work of anthropocenic marking. It is very frequently argued that Earth’s oceans became recognizably modern, epistemologically and technologically speaking, around the middle of the nineteenth century.41 It is possible, and I believe useful, to describe this becoming-modern in terms of the empirical revelation of marine character and contour. Like the fulfillment of the Nereides’ dream, scientific voyages began—and never stopped—facilitating the appearance (or confirmation) of untold kinds of living forms. Unfortunately, and due in part to what I think is a simplistic understanding of “premodern” oceanity, the literariness of marine and submarine knowledge has been mostly ignored, and sometimes expressly dismissed.42 (Marine biologist Rachel Carson’s conviction that it is impossible to “write truthfully about the sea and leave out the poetry” is the exception that proves the case.)43 In a notable instance of what journalist Elizabeth Kolbert calls “Anthropocene irony,” ostensibly obsolete sensibilities declare their relevance at exactly the moment we ask where and when to fix our having entered an unprecedented era.44

These entanglements highlight a small but meaningful part of the promise of—and challenge for—the work the Anthropogenic Markers collective has done, is doing, and will do. In confronting the unavoidable truth that anthropocenic oceans are sites of and for reading and writing, we can better comprehend the rich, strange weave of image, mode, and genre that inflect even our most resolutely future-oriented research projects with complex, and sometimes surprising, inheritances. Better still, by attending to the ramifications of the inaesthetic and the unforming of our intersecting literary and scientific knowledges, we may find our collective way toward expressing fears and hopes that are manifestly real but too rarely articulated. It is my cautious hope that reckoning together, collegially and across disciplines, with these layered and contentious formations and deformations might help us better shape, unshape, and reshape our stories and feelings for the world’s seas. Sensing more deeply the stakes for the expression of changing seas, we might even discover—and rediscover—some more promising futures in oceanic form, lived, written, and read.

Killian Quigley is a research fellow at the Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences, ACU and honorary postdoctoral fellow at the Sydney Environment Institute, University of Sydney. He is the author of Reading Underwater Wreckage: An Encrusting Ocean (forthcoming), the co-editor of The Aesthetics of the Undersea, and an associate with the Oceanic Humanities for the Global South research network.

Please cite as: Quigley, K (2022) Reading the Anthropocene Ocean. In: Rosol C and Rispoli G (eds) Anthropogenic Markers: Stratigraphy and Context, Anthropocene Curriculum. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. DOI: 10.58049/ppqy-vd84