Human-Mineral Classification

Taxonomy, Totemism, and the Technofossils of the Anthropocene

There has never been “pure matter.” The Western definition of minerals as simple substances emerged from an intricate interconnection of practical issues dealing with value, weight, and measurement. From this vantage point, the concept of a technofossil represents an innovation in how it explicitly mingles human agency with geological classification. In search for the normative elements of this new material domain, historian of science and cultural scholar Anna Echterhölter reflects on this history of mineral classification in the European tradition and the thick classification of Pacific totemism.

Technofossils and a twofold disarray

Since the mid-twentieth century, matter has been becoming less and less “natural.” Geological forces are no longer the sole drivers of the formation of solid substances. A term suggested by geologists for these new formats of “earth” is “technofossils.” They have begun to cover the globe and constitute its most recent strata. Among them are chemical artifacts like boron nitride and tungsten carbide as well as “mineraloids” such as artificial glasses and plastics.1 Likewise, defunct products factor into this category, from kitchen appliances to concrete rubble. “Technofossils” may be mistaken as an attention-seeking new label for the by-products of the industrial age or seen as a first-rate taxonomic provocation. The suggestion laid out in the following paragraphs is to instead think of technofossils as a first-rate conceptual innovation.

Due to their reliable presence, technofossils are part and parcel of Western science’s conception of material and earthly matters. But while natural minerals could be considered the best examples of “matter” or “physics” around—they are visible, tangible, stable, and hence obviously real—these new minerals and compounds only pretend to be natural matter, and geological forces alone cannot explain their existence.2 For example, minerals are, by definition, formed by geological forces—and yet around 5,100 recognized mineral specimens occur in artificial settings like mines. Around 200 accepted and ratified mineral specimens like Delrioite, Schuetteite, and Widgiemoolthalite do not emerge from “natural” procedures at all. Thus, quite a few mineral entities have to be considered as at least partly synthetic.3 Within the framework of traditional geology, it remains odd that minerals occupy the same classificatory space as rocks and metals.

From the perspective of chronostratigraphy, technofossils function much in the same way as fossilized organisms, which occur only in select geological strata. They are occurrences in nature, have a factual, material existence, and offer important signals. Just as the beginning of the Devonian period is indicated by fossils of a new species (Monograptus uniformis), technofossils may be what’s chosen to mark the onset of the Anthropocene. Whatever the case, this class of materials can be considered the expression of “the geology of mankind”4 on the level of mineral classification.

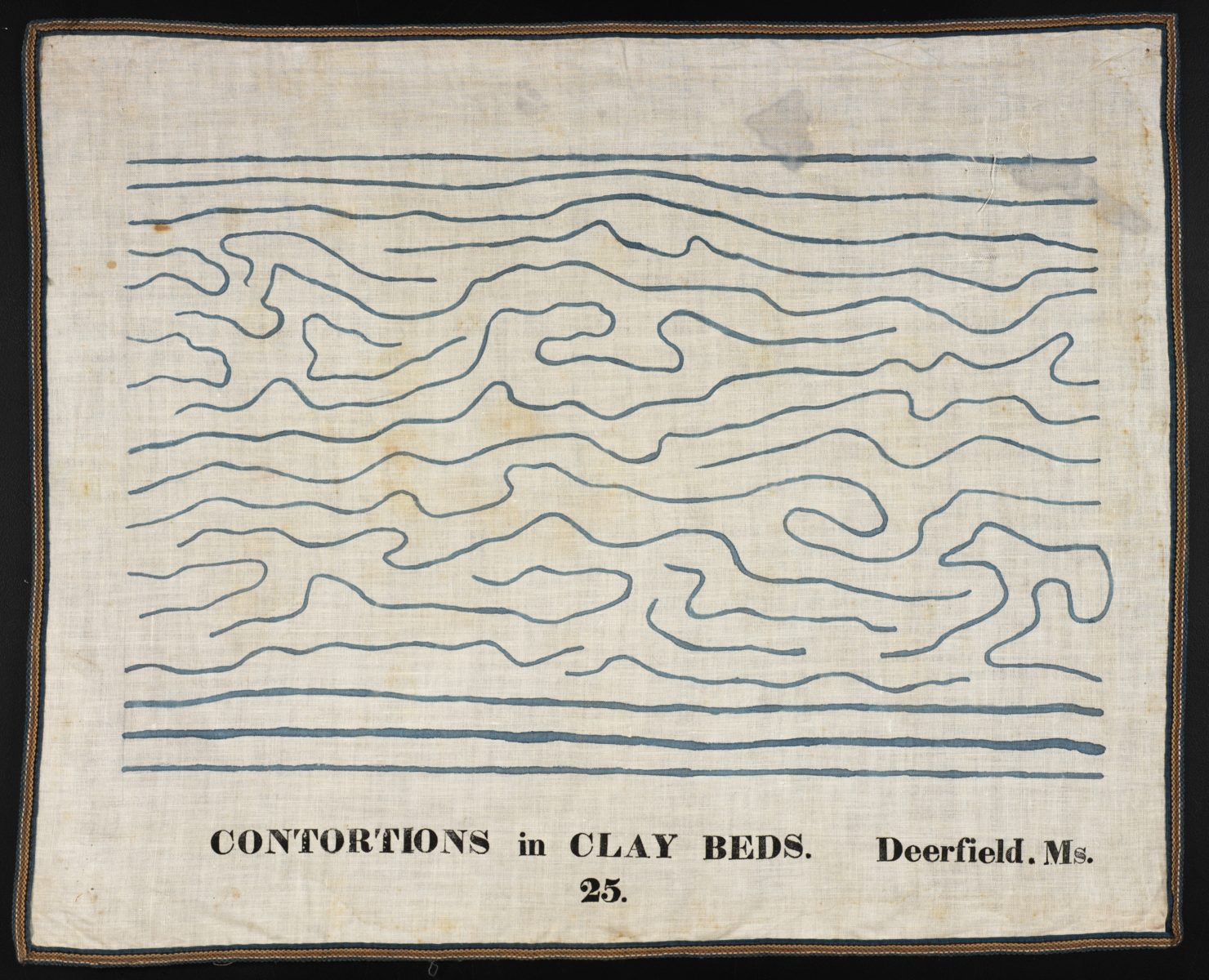

Animals or nature? Orra White Hitchcock’s drawing of contortions in clay beds were used in geology classes by her husband Edward Hitchcock around 1836-1840, who began to systematize geological traces that show biological activity. Drawing by Orra White Hitchcock, courtesy Archives & Special Collections at Amherst College, public domain

But it upsets this order at the same time. Technofossils confound the three kingdoms of nature (animal, vegetable, mineral) and constitute an awkward artificial-mineral-human realm. And it is this seeming disarray that may prove to be a truly radical innovation. Crucially, this nongeological matter brings to the fore the extent to which our perception of the physical world hinges on conceptions like organic versus inorganic matter and the division between nature and artifice. One cornerstone of modern mineralogy is the concept of simple substance, which describes a chemical element in its purest form. What ultimately makes technofossils intriguing is the double provocation they embody for the conceptual architecture of mineralogy. On the one hand, “technofossils” seems to be a necessary term—rather factual and descriptive of what is happening on the ground, in the physical world, on a global and massive scale.5 Yet, the idea of the technofossil is at odds with the central conceptualization of the geological force of mineralogy, since technofossils are a result of human, not solely geological, production. This is the first disarray they cause. Technofossils also do not sit well with the descriptive terms customary to the geosciences. Reproach and even accusation resound in this new term, as if these modern fossils constituted a “wrong” thing, a step too far: technofossils are conceptualized as illegitimate and misplaced matter. Ultimately, it is impossible to conceive of technofossils without at least a faint echo of ecological scandal. This inherent normative element is the second dimension of technofossil disarray. Thinking with this concept entails delineating “what ought to be.” Socioecological implications clearly constitute a breach in the tradition of mineralogical classification, which so far has kept people and the sphere of their actions out of the picture. Now the geological record is suggesting otherwise. Truly, though, technofossils amalgamate humankind and rocks in an awkward manner. This new group of mineral pretenders describes more than matter: it includes new ways of becoming nature, along with a certain sense of alarm.

To shed light on the twofold provocation of these mineral types (geological versus human-made, descriptive versus normative units), we’ll now revisit two historical instances of mineral classification from the vantage point of the history of concepts.6 The first case study looks at examples from Germany regarding the development of the simple substance concept over the course of the eighteenth century. It will establish the cornerstones of mineralogical classification and draw on research emphasizing the logics and practices of precise measurements of value, which form the immediate context of the “simplicity” or “purity” of a substance. The second case study returns to an episode from the history of ethnography. It touches upon an alternative classification of stones according to totemic imaginations described by ethnographers in relation to several Pacific Islander societies. In both cases, we’ll pay attention to the local and universal meanings of the scales involved, as they order minerals and situate their specific meanings within particular times and places on the globe; Anthropocene perspectives, of course, should always challenge us to consider such issues in terms of larger scale and specific locality.7 Both revisions show how classificatory systems of matter depend greatly on particular socioeconomic practices. The latter explain specific modes of mineral classification in all cases more precisely than the introduction of the “human species” in general as characteristic of the new era of the Anthropocene.8

From this vantage point, it becomes less surprising that human agency and social concerns are invested in notions of what a mineral specimen is. Technofossils are not remarkable because, with a closer look, human-mineral relations can be deciphered. Rather, they are a conceptual innovation from within the context of the Western scientific tradition because they explicitly mingle human agency into geological classification and because they do so with loud normative claims. The scandal of transgressing the former confines constructed around human action resounds with their very existence. The normative overtones of technofossils portend the extinction of species occurring around us, and thus the classificatory term gestures implicitly toward a new and cautious version of economizing resources. The emphasis on “technofossils as conceptual innovation,” spelled out in the following passages, complies with social historical concerns surrounding quantification that call for complex readings of apparently neutral concepts like metrics, data architectures, classificatory systems, concepts, standards, scales, and (mineralogical) units.

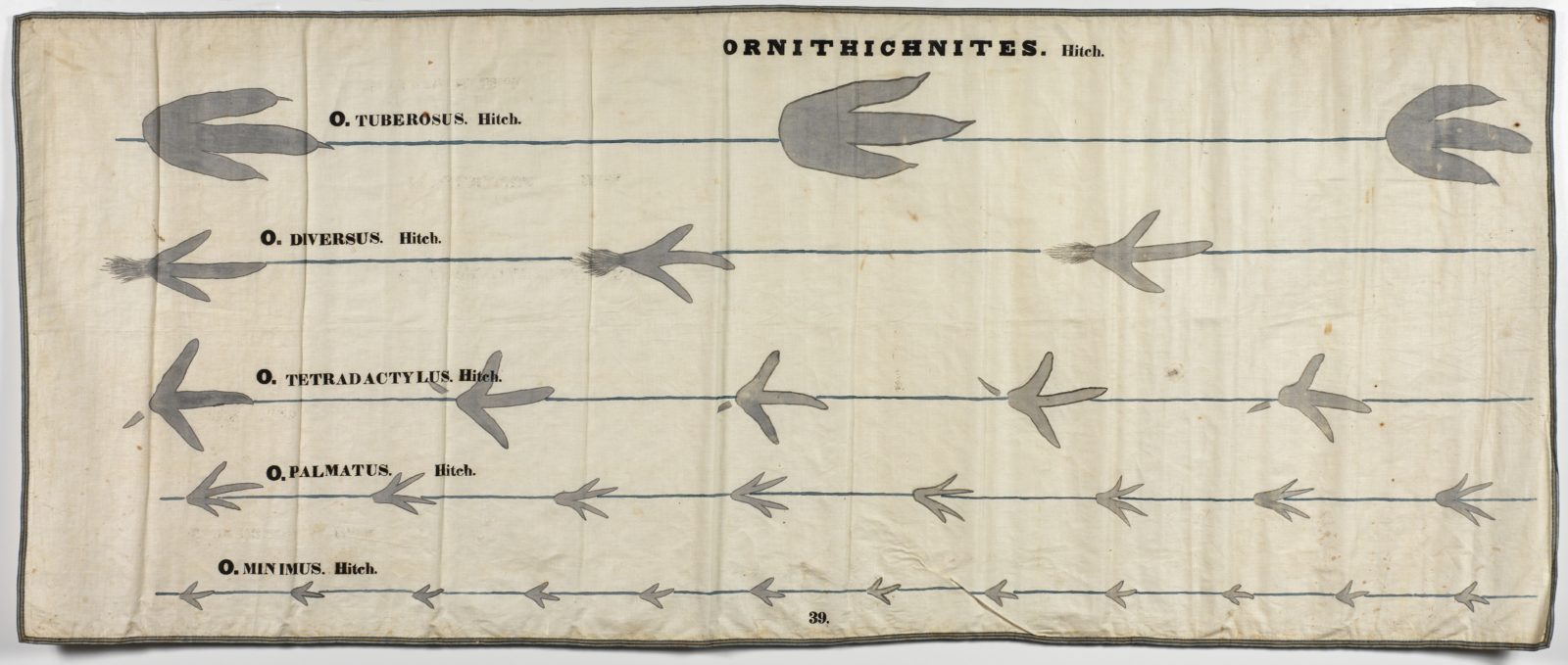

The history of trace fossils begins with footsteps. In this case they testify to the “Ornithichnites”—marks left by five kinds of walking birds. Educational drawing by Orra White Hitchcock for use in her husband’s classes on geology and natural history (1836-1840). Drawing by Orra White Hitchcock, courtesy Archives & Special Collections at Amherst College, public domain

Simple substance and mineral value

Brass and iron, bricks and sandstone—the sense of familiarity of these pairings derives from a history of smelting and construction practices. For a taxonomic point of view, these forms of matter are worlds apart. While iron and sandstone occur in nature, brass and bricks are human-made. Thus, we can see that artificial compounds match and rival those that are the product of geological forces, although some are more readily perceived as “natural” than others.

Even minerals, though, which are formed by the Earth, are rarely pure and simple enough in nature to live up to the mineralogical classes. Clearly, an overwhelming preponderance of “mixed” matter exists in nature. Even substances like gold or copper, which can be found in fairly pure states, are typically refined, further purified, and turned into more homogenous versions of themselves by humans. This raises the question as to why mineralogy began working with these idealized pure states in the first place, and where and in which contexts this core conception of mineralogical classification emerged.

Mineralogy, as a body of formalized scientific knowledge, consolidated in the West over the course of the eighteenth century. While simple kinds of mineral taxa surfaced in Swedish and German publications from the 1730s onward,9 the impulse to purify can be traced way back to technological literature on assaying and hallmarking beginning in the 1550s.10 As such, there is good reason to believe that the analytical definition of simple substance, which is key to chemical procedures, did not emerge from progress in chemistry or laboratory precision weighting alone, as some have suggested. Instead, this logic of “pure matter” can be strongly identified with the measurement of highly valuable ores—and so its history likely extends into mining, assaying, minting, and the administrative surveying of money issues, especially the policing of weighting systems related to coin production. This highly specialized area of precision was focused on the purity of gold, silver, and copper. Technical knowledge and ownership thus developed in lockstep. Where high value is involved, there is very good reason to quantify with accuracy and to monitor and consistently measure the purity of a substance.11 And, indeed, we find that mineral classification using the notion of simple substance first occurs in books describing the art of assaying monetary metals.12

According to historian of science Theodore Porter, mineralogists and chemists such as Torbern Bergman and Antoine Lavoisier simply transferred this perspective from the mines and the assayer’s workshop to the laboratories of chemistry. From here, purity, inseparability, and simplicity were imported into chemical analysis, as a practical logic, and thus transposed into the laboratory sphere. All this helped to practically and substantially arrive at the taxonomy of elements on which the mineral taxonomy came to be built.

Naming practices were one facet of this ongoing attempt to find states of matter that could not be separated any further, even by experimental means. Chemical analysis, and later crystallography, which classifies crystals according to their angles and internal structures, became more and more important in making sense of the sweeping variety of minerals that naturally occur in the Earth.

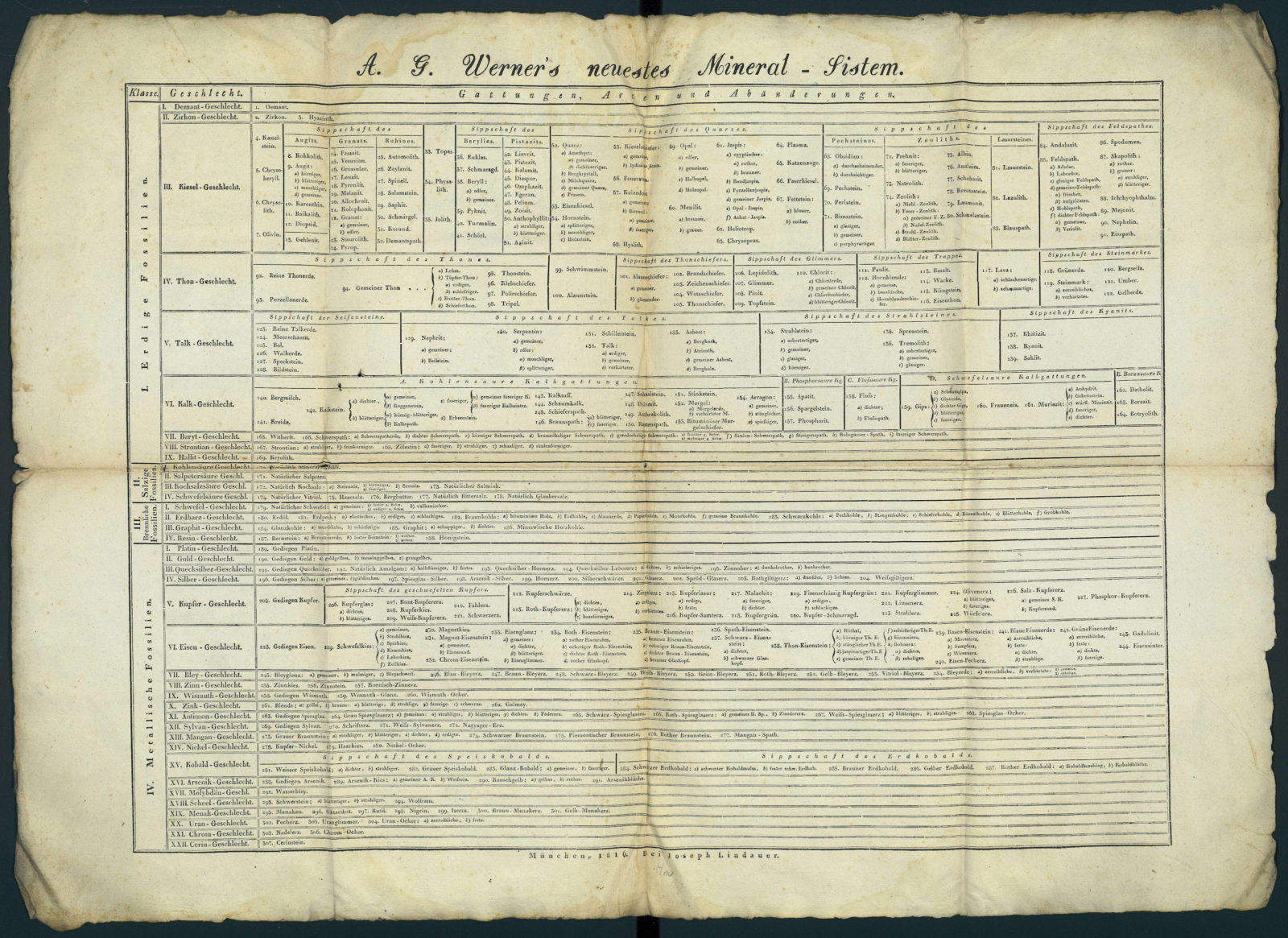

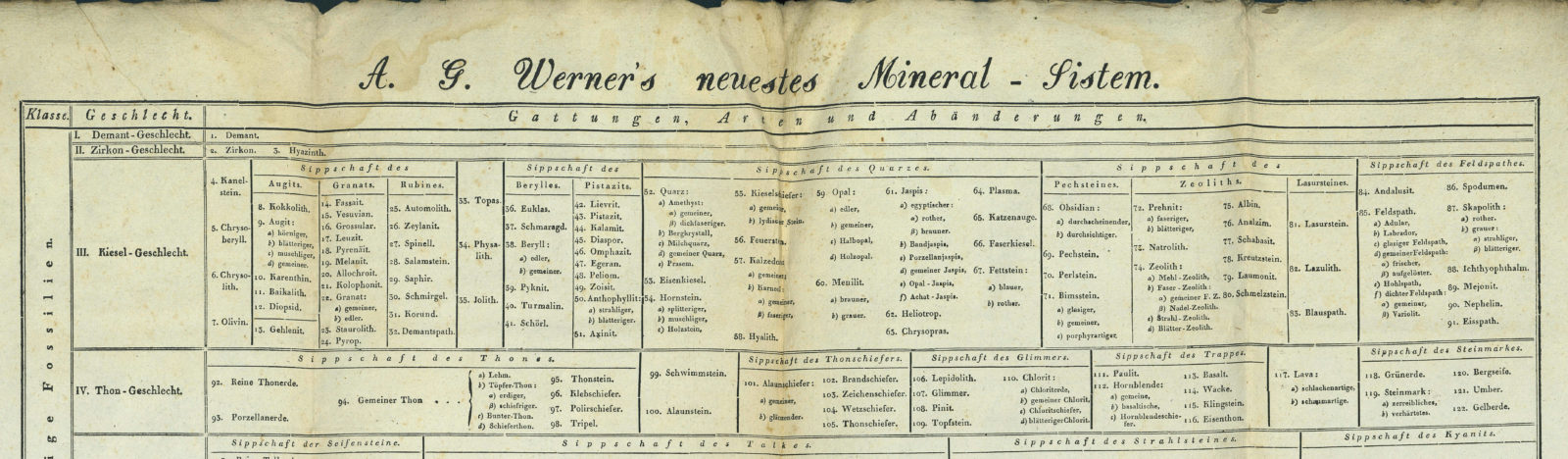

These developments, though, did have their adversaries. It was by no means an easy task to universalize the classificatory order of simple substance in practice. The very successful mineralogical school associated with Saxon mining is a case in point. At the end of the eighteenth century, German aristocrats from Novalis to Alexander von Humboldt flocked to the remote mining town of Freiberg to hear the geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner explain the emergence of mountains (Geognosie) and to determine what constitutes minerals and rocks (Oryktognosie).13 Werner’s brand of mineralogy can be considered a stronghold against abstract and purified ways of classifying minerals, as he rejected criteria such as chemical composition and physical properties such as the magnetic or electrical behaviors of a substance. As the title of his influential classificatory textbook reveals,14 Werner opted to focus on the “outward characteristics” of minerals—a decision usually explained by his aversion to identifying an arbitrary order in nature. He insisted instead on the “natural suite of bodies,” which was tantamount to considering the mineral taxonomy to mirror natural order itself.15 The quest to find a “natural” system of classification was a pursuit throughout the various branches of natural history.

Earlier explanations for Werner’s refusal to switch to chemical analysis and the “inward characteristics” of modern science hinged on a philosophy of the senses, which, in his opinion, were the only organs necessary to arrive at the true order of mineralogy in its entirety and perfection.16 All necessary information could and had to be obtained through outward criteria of color, weight, smell, taste, solidity, smoothness, coldness, and the like.17 Furthermore, recent research into the practices of mining have opened another and less phenomenological angle on the history of mineralogy, namely the fact that the various professions that utilized this technology cultivated an unwritten, unformalized form of classification of matter according, precisely, to practical needs. Werner himself opted for a fivefold order of “rock” only a few years before publishing his system of mineralogy,18 and this order corresponded with the five technologies then available to process rock and exploit mining sites.19 This “local” knowledge with its practicability may have been yet a more mundane reason to stick to outward criteria.

Courtesy Die Äußere-Kennzeichen-Sammlung von Abraham-Gottlob Werner, TU Bergakademie Freiberg. Courtesy Die Äußere-Kennzeichen-Sammlung von Abraham-Gottlob Werner, TU Bergakademie Freiberg. Courtesy Die Äußere-Kennzeichen-Sammlung von Abraham-Gottlob Werner, TU Bergakademie Freiberg. Courtesy Die Äußere-Kennzeichen-Sammlung von Abraham-Gottlob Werner, TU Bergakademie Freiberg. 6 of 249 brightly colored plates, which helped to classify minerals according to criteria which were still accessible to human sensual perception. Fabricated from Meissen porcelain after 1814, the plates now form an important part of Abraham Gottlob Werner’s comprehensive object collection on “outward criteria” of minerals. Courtesy Die Äußere-Kennzeichen-Sammlung von Abraham-Gottlob Werner, TU Bergakademie Freiberg. Gerhard Heide, Andreas Massanek, Beata Heide, Photography: Susanne Paskoff, Freiberg (Inv.-Nr.: 111021 / 111050 / 111105 / 111114 / 111125 / 111244) Courtesy Die Äußere-Kennzeichen-Sammlung von Abraham-Gottlob Werner, TU Bergakademie Freiberg.

In fact, for Werner and his contemporaries, a switch to a system based on simple substance and the internal criteria of minerals—requiring laboratory chemical analysis—would have meant making mineralogy less accessible to general users, including amateur mineralogists and dilettantes, and narrowing its application in the field.20 These wider mineral audiences could practice their pastime much more reliably by adhering to the minute color codes and sensory descriptions advocated by the field guides of the day, such as the one published by Johann Georg Lenz, professor of mineralogy, in 1798.21 Apprehending and describing the exact graduation of sharpness or a specific shade of a green that is milky and yellow at the same time was challenging and required training.22 While more accessible, determining outward characteristics nevertheless required an eye rehearsed in classificatory observation.

Thus, the classificatory criteria chosen by Werner—one of the most influential experts of his time— proved to be motivated by a context of professional mining combined with a consideration of wealthy citizens and collectors interested in minerals. He seems to have had very good reasons to resist abstract classificatory criteria like those suggested by crystallography and chemistry, instead sticking to a schema based on workflows, the senses, and the outward characteristics of the mineral specimen. However, while practical mining concerns and the interests of collectors stood up to internal characteristics for a little while, it eventually became too difficult to disentangle the units or taxa of mineralogy from the idea of matter, which, still to this day, is conceived in terms of simple substance and pure form.

To return to the question of how the concepts crucial for the emergence of scientific mineralogy are telling of human and economic concerns, Werner’s insistence on “outward characteristics” are an interesting case. They refuse to cut work practices, natural philosophy, or human sensual perception out of the equation. Yet, while humans began to disappear from the conceptualizations of scientific mineralogy, the latter still bear the mark of a distinct socioeconomic context. The abstractions of pure matter, which only emerged around Werner’s time, clearly spoke to the logic of the production of money, and while the idea of pure matter superseded the perspectives of workers or dilettantes in mining and mineralogy, simple substance nevertheless has to be understood as an expression of the developed state of capitalism. This socioeconomic setting made mineralogy less explicitly entangled with human concerns on a conceptual level, but such concerns remained an implicit political economy inscribed into the modes of classification nevertheless.

Werner's neuestes Mineral-Sistem [sic].“ München 1816. Courtesy Collections patrimoniales numérisées des bibliothèques de l'Université de Strasbourg, public domain

Mineral totemism as thick classification

Totemism—as an expansive categorization system that incorporates both humans and nonhumans—caught the attention and theoretical imaginations of European ethnographers around 1900. These researchers reported upon societies, located everywhere from North America to Oceania, that were ordered around a particular thing—a thing that exerted an inexplicable power over the people and their behavior. Both organic and, occasionally, inorganic objects could be elevated to this eminent position of a “totem.” From the start, ethnographers investigated totemism as a curious mode of classification that placed humans, in an uncommon way, in the same system with plants, animals, and sometimes even minerals. One of the first famous researchers studying the phenomenon, the ethnographer James George Frazer, maintained: “As distinguished from a fetich, a totem is never an isolated individual, but always a class of objects, generally a species of animals or of plants, more rarely a class of inanimate natural objects, [and] very rarely a class of artificial objects.”23

This class of nonhuman things served to bind human social ties. Totems reigned over sexuality, religious belief, consumption, war and peace. The term for this comprehensive classification, “totem,” was derived from an Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) word.24 Questions about totemism appeared on the first pages of ethnographic questionnaires,25 Indigenous travelers on steamboats traversing the Pacific were pressed for information about their “native lands,” missionaries were cross-examined about their observations, academic journals published series on totemism, and, eventually, experts from the aforementioned Frazer to Sigmund Freud wrote monographs on the subject.

In 1900 the ethnographer W. H. R. Rivers observed how water, fire, and a bowl were raised to the status of a totem, in a small island between Australia and Papua New Guinea.26 Rivers even met a local informant who claimed his personal totem, or atna, was “a large stone called Kalinga.”27 While this case of “mineral totemism” is rather rare, specialists estimate that around one-fourth of the recorded cases of totemism diverge from the more typical animal and plant totemism, and promote body parts, abstract numbers or clouds into the status of ancestors.28

Societies structured according to this principle displayed a particular social order. People conceived of themselves as descendants of the totem, and the totem also organized relations between groups unconnected by kinship but held together by a shared strong relation to the chosen entity. These relations described a specific logic of care: even if people all came from the same village, those who belonged to different totem groups might be treated in a more negligent fashion.

What is more significant, here, to a history of the human-mineral relationship is that aspects and responsibilities assigned to the totem object also extended to members of the totem group. Thus, the totem could mandate certain behavior; for example, “the wire or water people may not drink the water of a certain bubbling pool; the members of the tegmete division may not eat food prepared in a bowl and the ambumni people may not walk on grass.”29 These restrictions are typical characteristics of totemism. Thus, the system not only proposes close, intimate ties between humans and nonhumans but also sets prohibitions and rules of usage. Humans are beholden to the totem and are required to abide by certain taboos. Grass or prey must be protected; walking and hunting are prohibited. A functionalist perspective readily interprets these taboos as resource management. While this remains a much debated approach, what is uncontroversial is that the totem order impinges on social order and interhuman relations in such a way that property and inheritance become organized along the same lines. That is, the same classificatory scheme serves as natural order, economic order, and social order in one. Resource economies, then, can be equated to totemism, in the sense that this classification determines usage of food and resources, determines obligations to care, and sometimes mandates the non-use of nature, which is understood as kin.

Although integrating all the rules governed by a totem object into one’s life might seem overwhelming, the contemporary ethnographer John Comaroff compares totemism quite favorably to societies structured around ethnicity. In totemism, the various social ties are structurally similar and less integrated into a dominant whole, whereas “ethnicity has its origins in the asymmetric incorporation of structurally dissimilar groupings into a single political economy.”30 Comaroff contends that ruptured power situations and post-conflict environments could act as potential catalysts for the development of totemism. He is interested in social ties that depend on natural objects much more than on bloodlines. Yet the particular form of classification enacted by totemism does not depend on inherited bodily characteristics, and so it does not perpetuate inequality in the same way as classifications according to ethnicity do, which naturalize belonging according to physiological traits that differ from a mainstream society.

Today, totemism as a framework through which to rethink or even reformulate relations between humans and nature is having a surprising revival. The ontological turn in ethnography offers an interesting take on older formulations of totemic taxonomies. For example, totemism looms large in Philippe Descola’s four ontologies (animism, totemism, analogism, and naturalism) and also speaks to Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s perspectivism, which spells out divergent modes of classification from the Amazonia. Such contemporary theory makes totemism (or animism) sound tantalizingly ecological.

This recent interest is all the more surprising given the role totemism played in supporting a surprisingly comprehensive list of ethnographic methodologies, from the pitfalls of evolutionary theory to the racism of Kulturkreislehre (cultural field school), and from narrow functionalism to the very heart of structuralism. Amid attempts to arrive at multispecies perspectives and non-Northern sustainabilities, totemism appears to be proving itself an unwieldy tool, which necessitates an analysis of ontological dimensions more broadly.

Notably—and maybe misleadingly—all this modern theorizing about this classificatory scheme points toward one latent promise: Could this differently ordered world offer an ecological advantage? It’s not easy to answer this question in the affirmative. Simply putting the romanticized elements of kindness, kinship, relationality, and ecological connectedness front and center does not help much. Nevertheless, considering how the conceptualization of matter prohibits or encourages behaviors and how it legitimizes and predetermines resource allocation is a timely and important investigation.

Instead of reifying this mode of human-nonhuman classification as ontology or cosmology, we could instead perceive it as a discourse, a particular way of asking question and making sense of things, which is way to perceive of the world, not its inherent structure.

Remarkably, this attempt to arrive at epistemological perspectives is what Descola seems to reject in perhaps his most famous predecessor, Claude Lévi-Strauss. For the latter, the totem animal, plant, or mineral is a resource for organizing differences. Totemic classification firstly allows for an intellectual order, and only subsequently are social groupings and social behaviors affected. For Lévi-Strauss, two images stabilize each other: one related to natural difference, the other to social belonging and responsibility. They occur on one inseparable plane of existence, governing nature as well as society with the same kind of law.31 Descola rejects Lévi-Strauss’ key fascination with this power of categorization, which he deems intellectualist, abstract, and infested with dichotomies. Instead of explaining social hierarchies as consequences of the capacity to group and regroup nature into a taxonomic logic, Descola’s world seems to structure itself more easily as a welcoming plenitude. There is no need to find cognitive dichotomies and sustain them in the outer world, to give it the structure of a totem and totem groups. Social discontinuities are not learned and transferred from conceptual ones, to Descola’s mind. He stresses the divergent anthropology of nature, which does not split visible matter into substantial and incidental, into true idea and negligible occurrence, humans and minerals, but rather departs from mighty streams of sameness, underlying matter, and “individuated organisms” alike.

Totemism is successful in dispensing with separate taxa. It encourages identification with natural elements—sometimes rocks—as totem groups while excommunicating fellow humans into another order. Under totemism, humans do not emerge from Adam’s rib. We all branch off from a first being, which remains part of the new entity. Human relation to nonhumans can be very deep in these schemes. The world is multiple flows of admixtures, a process that not even time can keep in check in the way we would expect descent or generation to work. The relation of the whole totem group exists outside the present and continues to resonate with processes that originated at the beginning of history. One key example of totemic conception is the “dreamtime” of Aboriginals in what is currently called Australia. In dreamtime, the beginning of mankind is actively felt in the present. Dreamtime coexists. It is by no means an epoch of the past, a time to remember, and neither a possible future.32 The ties binding people and landscapes into units over time are vivid and substantial lived realities, not abstract taxonomies. What Descola terms “relation” is more unrelenting then a mere psychoanalytical emotion felt toward an object. It is richer and less voluntary than the insights that arise in a shared classificatory order.33

While Descola describes naturalism—the typical ontology of the Global North and a counterpart to totemism—in critical terms, and lists it as one of the fourfold modes of being, he writes much less about actual nature than one might expect. Naturalism divides humans into a physical and spiritual existence: half angel, half animal.34 While Descola’s strongest move seems to be the distance he claims to old-world, self-evident, intellectualist concepts, there is probably no better reading than Descola to experience the profound difficulties of seeing beyond them—to reconceptualize nature, to leave the world of simple substance and to follow other modes of human-mineral adhesion.

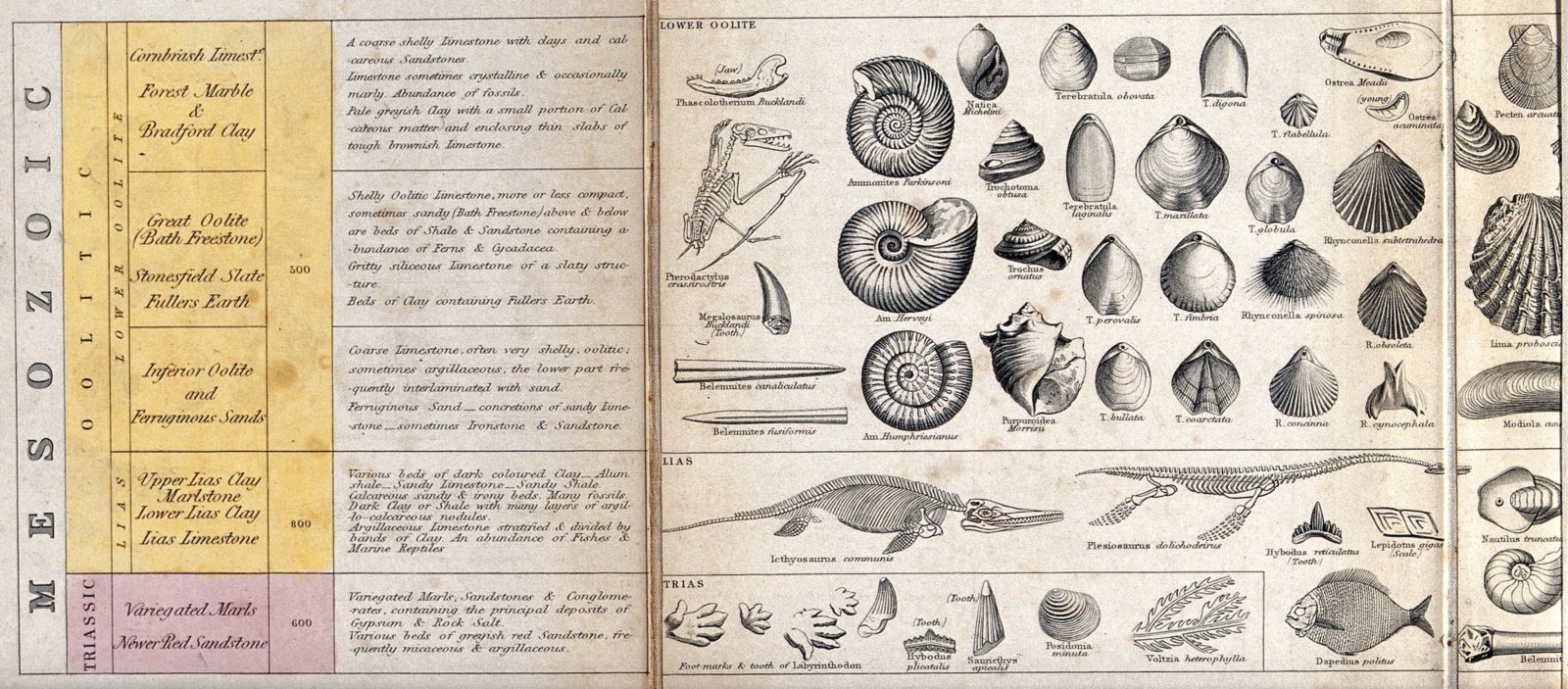

Life on Earth. Mesozoic British fossils, arranged in a stratigraphical order with a legend on the left side and captions under each fossil. Courtesy Wellcome Collection, public domain

Outlook on the normative elements of Anthropocene classification

Compared to the history of totemism, the twofold disarray that technofossils cause within mineral classification may seem faint, tame, or even narrow. Nevertheless, the suggestion of this text is to value them as a conceptual revolution judged against the history of mineralogical taxa. Given that technofossils are a still novel but widespread physical phenomenon, geological conceptualization has to eventually adapt to the new realities produced on Earth. The small provocation posed by this conceptual innovation in geology is thus still a part of the natural sciences, but it cannot avoid stirring up disarray. Technofossils developed in analogy with petrified forms of life, namely fossils. Even trace fossils fit into categories set according to mineral taxonomies, yet their names pay witness to some activity of living beings, albeit in a way much smaller than the agency claimed by humans, who have become a geological force. Fossils are categorized as, for example, domichnia (dwelling structures), repichnia (surface traces of creeping and crawling), or fugichnia (escape structures).35 Technofossils were modeled on these taxa and incorporate the agency of living organisms. They provoke the clean-cut order of simple substance, in that technofossils always imply human activities and prohibit stripping the classificatory orders of any social meaning. As was shown during our dip into the history of mineral classification, simple substance—neutral as it may seem on the surface—can be read as an expression of a particular economic activity or desire. Admittedly, these economic meanings remain implicit and surface only in historical perspectives.

Technofossils do, of course, have an industrial signature and can by no means be equated with totemic classifications, which are typically found in nonindustrialized societies. What is evident, though, is that both of these modes of classification make the human-mineral relation explicit. While in totemism classes of objects exert a power that structures behavior toward other humans and nonhumans alike, the present upsurge of new matter embodies a different relation. Neutral and relationless human agency is what produced and amassed this new layer of technofossils around the globe, which will never be quite natural again. Thus, all three modes of classification—Enlightenment-era mineral classification, totemic classification, and the new taxa of the Anthropocene—speak to a typical economic structure. The fate of society, or at least some element of economic significance, is pulled into the wake of the mineral classificatory system. All three modes of classification imply human agency and mirror economic ways of conceptualizing minerals and organizing resource access and protection. Even seemingly neutral mineral classifications justify certain uses of matter. What is newly introduced by technofossils, however, is that the normative element encapsulated by this notion seems to explicitly suggest a misuse of resources. It could be argued that this normative element makes mineralogy more human compared against the history of mineral classification, and due to the new physical dependence of technofossils from human production it may even be considered a step towards the strong links of humans, though in reversed order compared to totemism. This makes thinking with technofossils a very promising conceptual revolution.

Anna Echterhölter is Professor of History of Science at the University of Vienna. Her research interests include economic exchange and metrology, standardization and colonialism, the history of quantification, and surveys of indigenous law in Oceania.

Please cite as: Echterhölter, A (2022) Ironies of the Anthropocene. In: Rosol C and Rispoli G (eds) Anthropogenic Markers: Stratigraphy and Context, Anthropocene Curriculum. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. DOI: 10.34663/c2vx-zd87